Analysis of Drivers of Spring Alligator Hunting in Texas And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Santee National Wildlife Refuge Road 2125 Fort Watson Summerton, South Carolina 29148 803/ 478 2217 U.S

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Rogers Road Santee National Taw Caw Refuge Creek Entrance Wildlife Refuge State Potato Migratory Creek Wildlife Drive Bird Information Sanctuary Kiosk Interpretive Guide 12 1 8 2 Woods Road 3 5 2 4 6 7 9 Cuddo West 1 11 Cuddo East North Loop 15 Black Bottom 3 Pond 10 Timber 14 Island Plantation Islands Field (proposed) 4 10 11 9 Wilderness Otter Trail Black 5 Area Bottom South Loop 13 12 8 Alligator Alley Hundred Acre Island Shuler's 6 7 Refuge boundary Round Auto tour route, interpretive markers 1-12 Island Foot access only Boundaries represented Bicycle and foot access only are approximate. Canoe trail, markers 1-15 Goat Cuddo and Area closed to all entry Island West November 1 until March 1 Santee National Wildlife Refuge Road 2125 Fort Watson Summerton, South Carolina 29148 803/ 478 2217 http://fws.gov/santee U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1 800/344 WILD September 2010 1. Santee National Wildlife Refuge 7. Bluebird boxes 10. Wildlife Drive - Otter Trail Starting at The Santee National Wildlife Refuge was established in 1941 Wooden boxes mounted on posts along the To continue down the Wildlife Drive, turn RIGHT at this as a migratory bird sanctuary. The refuge boasts nearly 300 edge of the road are nesting boxes for eastern intersection. the Cuddo bird species recorded on the refuge. Mammal species found bluebirds (Sialia sialis), which nest on the refuge Wildlife on the refuge include white-tailed deer, beaver, river along field and forest edge habitats. Bluebirds 11. -

Alligators and Be Prepared for a REAL Gullible

Texas Wildlife Association presents.... June 2013 Kid’s Quarterly Mini-Mag! Vol. 7 No. 2 Postcards from Nancy....By Cara Bierschwale Howdy, Partners! “AHH!” he exclaimed. “Bigfoot track!” Grant pointed to Only three miles west of crossing the border into Louisiana, the muddy ground at a large, deep print. It was almost a Grant the Gopher and I are in deep East Texas spending some foot long! My heartbeat raced as I tried to make sense of the time at Caddo Lake State Park in Karnack, Texas. This area is situation. Just then, Grant and I turned around 25,400 acres of lake, wetlands, and beautiful cypress forests towards the sound of something large sliding located right on the border between Texas and Louisiana. and swooshing along the mud behind us. Our Caddo Lake is named for the Caddoans, Native Americans that eyes focused in the dark on some movement lived in the area, and until the early 1900’s this was the only by the reedy bank, and the last thing we saw natural lake in Texas. before sprinting back to camp was something Grant and I came here on a mission: to find evidence of slipping into the dark, rippling water. the legendary Bigfoot. Grant said that there are When we stopped at the same actual reports of Bigfoot sightings around this little store on our way home, Grant Footprints in the mud by Grady Allen lake, and since he believes everything he sees gave the cashier an elaborative on television, he begged me to join him in hopes account of our amateur sighting experience. -

Alligator Awareness

Brochure_Layout 1 8/4/17 9:52 AM Page 1 (including hunting) their own alligator populations. ties each year as a result of nuisance complaints. hunting season. The initial area open to alligator hunt - Management plans still had to be approved by USFWS However, every nuisance complaint call does not result in ing was a 16.5-mile portion of the Pearl River north of and alligators had to be tagged with a CITES the removal of an alligator. Many alligators are removed the Ross Barnett Reservoir, which is home to the densest (Convention on International Trade in Endangered as a result of being in “out-of-place” locations, such as population of alligators anywhere in Mississippi. In 2013, Species) tag. “TSA” refers to the fact that alligators, or residential ponds or yards, swimming pools, marinas, limited alligator hunting opportunities expanded more specifically alligator hides and parts, are very dif - and highways. statewide, on public waterways. ficult to distinguish from the hides and parts of other Numerous complaints are received because alligators endangered crocodilians such as the American Crocodile have lost their natural fear of humans and human activ - To report a nuisance alligator or persons violat- (Crocodylus acutus) or the Chinese Alligator (Alligator ity. This behavior is usually the result of people purpose - ing alligator regulations call your local MDWFP sinensis). ly or indirectly feeding alligators. Feeding alligators is District Office or 1-800-BE-SMART. illegal in Mississippi, due to obvious concerns and danger The Mississippi Alligator Program that can develop when alligators begin to associate a food North Region Office (662) 563-6222 In the 1960's and 70's, alligators from Louisiana were source with human activity. -

By Aaron Feigenbaum

by Aaron Feigenbaum 1359_COVER.indd 1 5/21/07 2:46:18 PM [Intentionally Left Blank] by Aaron Feigenbaum Consultant: Laura A. Brandt, Ph.D. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Team Leader, Joint Ecosystem Modeling Lab Fort Lauderdale Research and Education Center 1359_Alligators_PDF.indd 1 5/23/07 12:00:58 PM Credits Cover and Title Page, © David Hosking/Alamy; 4, © Thomas McCarver; 5, © William Munoz; 6, © Lynn M. Stone/naturepl.com; 7, © W. Perry Conway/Corbis; 8, © Robert Pickett/Papilio/Alamy; 9, © Martin Woike/FOTO NATURA/Minden Pictures; 10, © Adam White/naturepl.com; 11, © P. Henry/ArcoImages/Peter Arnold, Inc.; 12L, © Lawrence Manning/Corbis; 12R, © W. Perry Conway/Corbis; 13, © The Granger Collection, New York; 14, © Peter Horree/Alamy; 15, © Kevin Fleming/Corbis; 16, © Raymond Gehman/ Corbis; 18, © P. Henry/ArcoImages/Peter Arnold, Inc.; 19, © Thomas McCarver; 20, © Thomas McCarver; 21, © Philip Gould/Corbis; 22, © William Munoz; 23, © AP Images/ The Post & Courier, Wade Spees; 24, © William Munoz; 25, © C.C. Lockwood/Animals Animals-Earth Scenes; 26, © AP Images/J. Pat Carter; 27, © Stan Osolinski/OSF/ Animals Animals-Earth Scenes; 28, © William Munoz; 29T, © Dr. Myrna Watanabe/Peter Arnold, Inc.; 29B, © W. Perry Conway/Corbis; 31, © magmarcz/Shutterstock. Publisher: Kenn Goin Senior Editor: Lisa Wiseman Creative Director: Spencer Brinker Photo Researcher: Amy Dunleavy Cover Design: Dawn Beard Creative Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Feigenbaum, Aaron. American alligators : freshwater survivors / by Aaron Feigenbaum. p. cm. — (America’s animal comebacks) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-59716-503-7 (library binding) ISBN-10: 1-59716-503-4 (library binding) 1. -

Coral Bay Indigenous Preserve and Protected Species Management Plan

CORAL BAY INDIGENOUS PRESERVE AND PROTECTED SPECIES MANAGEMENT PLAN April 2021 Prepared For: D.R. Horton 10541 Six Mile Cypress Parkway Fort Myers, Florida 33966 (239) 225-2631 Prepared By: Passarella & Associates, Inc. 13620 Metropolis Avenue, Suite 200 Fort Myers, Florida 33912 (239) 274-0067 Project No. 20DRH3329 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1.0 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 1 2.0 Existing Indigenous Vegetation Preserve .......................................................................... 1 3.0 Indigenous Vegetation Preservation and Restoration ........................................................ 1 4.0 Methods to Remove and Control Exotic and Nuisance Plants .......................................... 2 5.0 Monitoring Reports ............................................................................................................ 3 6.0 Protected Species Management Plan ................................................................................. 3 6.1 American Alligator Management Plan .................................................................. 3 6.1.1 Biology ....................................................................................................... 4 6.1.2 Management Plan....................................................................................... 4 6.2 Gopher Tortoise Management Plan ....................................................................... 5 6.2.1 Biology ...................................................................................................... -

Nuisance American Alligators: an Investi- Gation Into Trends and Public Opinion Cord B

Human–Wildlife Interactions 8(1):5–21, Spring 2014 Nuisance American alligators: an investi- gation into trends and public opinion CORD B. EVERSOLE, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University, 1150 Engi- neering Avenue, MSC 218, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA [email protected] SCOTT E. HENKE, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University, 1150 Engi- neering Avenue, MSC 218, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA JACOB L. OGDEE, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University, 1150 Engi- neering Avenue, MSC 218, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA DAVID B. WESTER, Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute, Texas A&M University, 1150 Engi- neering Avenue, MSC 218, Kingsville, TX 78363, USA AMOS COOPER, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 10 Parks and Wildlife Drive, Port Arthur, TX 77640, USA Abstract: The population rebound of the American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis; hereafter, alligator), with the rapid growth of populations throughout its range, has caused an influx of human–alligator conflicts. We quantified 5,838 nuisance alligator reports from 2000 to 2011 to develop more site-specific strategies of management and to determine where management should be focused to minimize the conflict. We also surveyed the general public’s attitude toward and knowledge of alligators (n = 98) as a technique to better understand human dimensions of nuisance alligator management in Texas. Counties that received the largest numbers of nuisance alligator reports were Jefferson (16%), Fort Bend (14%), Matagorda (11%), Brazoria (10%), Harris (7%), Jackson (5%), Orange (5%), Chambers (5%), Calhoun (5%), and Liberty (3%) counties. We found that of the nuisance alligators reported, 45% were male, 18% were female, and 38% were reported as unknown. -

Evaluating Behavior and Enclosure Use of Zoo-Housed Broad- Snouted Caiman (Caiman Latirostris): a Case Study in the Zoo of Córdoba (Argentina)

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(3):601–614. Submitted: 1 May 2019; Accepted: 15 October 2019; Published: 16 December 2019. EVALUATING BEHAVIOR AND ENCLOSURE USE OF ZOO-HOUSED BROAD- SNOUTED CAIMAN (CAIMAN LATIROSTRIS): A CASE STUDY IN THE ZOO OF CÓRDOBA (ARGENTINA) LILEN PRYSTUPCZUK1,2, GERARDO C. LEYNAUD1,2, AND M. CARLA LABAQUE3,4,5 1Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas, y Naturales, Centro de Zoología Aplicada. Rondeau 798, Córdoba (5000) Argentina 2Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Instituto de Diversidad y EcologíaAnimal (IDEA), Rondeau 798, Córdoba, (5000) Argentina 3Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales, Catedra de Ecología, Avenida Vélez Sársfield 299 (X5000GCA), Córdoba, Argentina 4Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas y Tecnológicas (IIByT), Avenida Vélez Sársfield 1611 (X5016GCA), Córdoba, Argentina 5Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Zoo environments represent a useful opportunity for animal research, particularly for species that are difficult to observe in the wild. Moreover, studying the behavior of zoo-housed populations provides important information about the welfare state of animals. We described the behaviors of a zoo-housed population of seven Broad-snouted Caimans (Caiman latirostris) composed of males and females of different ages. We evaluated the associations of behavior frequencies with attributes of individuals (sex and age class) and with environmental variables (season, time of the day, and daily mean temperature). We calculated the Spread of Participation Index to estimate the use of space in relation to attributes of individuals and environmental variables. Additionally, we evaluated the suitability of the enclosure and management measures by assessing the Five Freedoms. -

Reversing America's Wildlife Crisis

ReveRsing AmeRicA’s WILDLIFE CRISIS SECURING THE FUTURE OF OUR FISH AND WILDLIFE MARCH 2018 REVERSING AMERICA’s Wildlife CRISIS 1 ReveRsing AmeRicA’s Wildlife cRisis SECURING THE FUTURE OF OUR FISH AND WILDLIFE Copyright © 2018 National Wildlife Federation Lead Authors: Bruce A. Stein, Naomi Edelson, Lauren Anderson, John J. Kanter, and Jodi Stemler. Suggested citation: Stein, B. A., N. Edelson, L. Anderson, J. Kanter, and J. Stemler. 2018. Reversing America’s Wildlife Crisis: Securing the Future of Our Fish and Wildlife. Washington, DC: National Wildlife Federation. Acknowledgments: This report is a collaboration among National Wildlife Federation (NWF), American Fisheries Society (AFS), and The Wildlife Society (TWS). The authors would like to thank the many individuals from these organizations that contributed to this report: Taran Catania, Kathleen Collins, Patty Glick, Lacey McCormick, and David Mizejewski from NWF; Douglas Austen, Thomas Bigford, Dan Cassidy, Steve McMullin, Mark Porath, Martha Wilson, and Drue Winters from AFS; and John E. McDonald, Jr., Darren Miller, Keith Norris, Bruce Thompson, and Gary White from TWS. We are especially grateful to Maja Smith of MajaDesign, Inc. for report design and production. Cover image: Swift fox (Vulpes macrotis), North America’s smallest wild canid, has disappeared from about 60 percent of its historic Great Plains range. Once a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act, collaborative state and federal conservation efforts have stabilized the species across much of its remaining range. Photo: Rob Palmer Reversing America’s Wildlife Crisis is available online at: www.nwf.org/ReversingWildlifeCrisis National Wildlife Federation 1200 G Street, NW, Suite 900 Washington, D.C. -

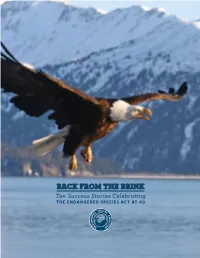

Back from the Brink Ten Success Stories Celebrating the Endangered Species Act at 40 Introduction Acknowledgements

BACK FROM THE BRINK Ten Success Stories Celebrating THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AT 40 INTRODUCTION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Success. We are constantly bombarded with messages about the to the Endangered Species Act, stories like these can be found in importance of success and how to achieve it. Search for a book every state across the country as imperiled animals, plants, birds, and about success on Amazon, and you’ll get not only the Seven Habits fish are stabilizing and rebuilding healthy populations. Indeed, most of Highly Effective People, but also more than 170,000 other books endangered species are on track with established recovery plans, on how to be successful at work, in friendships and relationships, and some are even reaching population goals ahead of their targeted and way more. Clearly, we place an incredible value on success. schedules. In this report, you will find ten success stories that are among the most compelling in the nation. But when it comes to protecting wildlife and wild lands, how do we define success? To some of us, the answer is obvious. But in On the 40th anniversary of the Act, it is time to celebrate our journey our highly charged political atmosphere, wildlife opponents seek as we have brought one species after another back from the brink of to narrow the definition of success in a concerted effort to weaken extinction. Passing this moral and noble law was the first step along a wildlife protections. Their thinking goes that, if they can convince new path for the United States. We were once a nation that believed us that our conservation efforts have not been successful, we will that rivers were meant to be dammed, forests to be completely clear cut, support getting rid of existing protections. -

DRAFT Savannah NWR Hunt Plan and Environmental Assessment

SAVANNAH NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE AMERICAN ALLIGATOR, ARMADILLO, BEAVER, OPOSSUM, AND RACCOON DRAFT HUNT PLAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT U.S. Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service Savannah National Wildlife Refuge 694 Beech Hill Ln. Hardeeville, SC 29927 March 2020 Table of Contents Section A. Draft Hunt Plan ............................................................................................................ 1 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 A. Refuge Land Acquisition History ....................................................................................... 4 B. Overview of Refuge Management ...................................................................................... 5 II. Statement of Objectives ............................................................................................................. 8 III. Description of Hunting Program ............................................................................................... 9 A. Areas to be Opened to Hunting ........................................................................................... 9 B. Species to be Taken, Hunting Periods, Hunting Access ..................................................... 9 C. Hunter Permit Requirements............................................................................................. 10 D. Consultation and Coordination with the State ................................................................. -

Quarterly Report September 2019

Quarterly Update • September 2019 Analysis of data collected from the 1st Wild Harvest Initiative® Wild Meat Sharing & Consumption Survey, administered in Texas, has begun, as we prepare to share initial program results. American Alligators are wild harvested in 8 jurisdictions in the United States. Their range does not extend into Canada. Species profile – American would have been consumable, or Endangered Species Act classification Alligator about 63%, based on typical “threatened due to similarity of Harvest in the United States consumption habits for this species. appearance” because some related Given a robust 6 oz. serving, this American Alligators (Alligator animals, i.e. caimans and some constitutes 12,571,093 meals over a mississippienis) have long been popular crocodiles, remain in peril. two-year period. for their skins and meat and, today, are The International Union for recreationally harvested in at least 8 Conservation Status Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists US states including Alabama, By the 1950s, American alligator the American Alligator as a species of Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, populations had reached all-time lows “Least Concern” in terms of extinction Mississippi, South Carolina, and across their native range in the United risk. Texas. Approximately 94,189 States. This was due primarily to American alligators were wild caught in these jurisdictions during the 2014- market-hunting and habitat loss. In 15 and 2015-16 harvest seasons. The 1967, the species was listed as total live catch had an estimated mass Endangered. However, in 1987, the of 6,122,285 kg (13,469,027 lbs) American alligator was pronounced which resulted in a dressed weight of fully recovered, making it one of the approximately 3,428,480 kg first endangered species success (7,542,656 lbs). -

Part 2 Our Wild Neighbors WN Bookedition2 2007 Fin 1/31/08 11:16 AM Page 65 9 ALLIGATORS

WN_BookEdition2_2007_fin 1/31/08 11:16 AM Page 63 Part 2 Our Wild Neighbors WN_BookEdition2_2007_fin 1/31/08 11:16 AM Page 65 9 ALLIGATORS T MIGHT SEEM surprising Ithat the Am- erican alligator was once highly endangered, given Figure 20 Alligator that the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conserva- tion Commission now receives ten thousand complaints about alligators annually (Figure 20). Once hunted nearly to the brink of ex- tinction for their skins, alligators rebounded under protective laws until now, an estimated o The low-frequency vibrations made by a male alligator just before his audible two million of these animals are living in the bellow are so powerful they can make wild today. The status they hold as threatened the water “dance” in a visual display is to help protect crocodiles, close relatives of droplets. who are truly endangered. Most people confuse alligators with croc- o Although alligators have existed odiles, even though the latter are only found unchanged for so long that they are in extreme southeastern Florida along the given the title “prehistoric,” there coast. Crocodiles can subsist in saltwater habi- is nothing primitive about these tats; alligators are better adapted for freshwa- sophisticated, complex animals. ter living. Most species of crocodiles have nar- row, “V”-shaped snouts. Alligators’ snouts are o In winter, alligators excavate “gator rounded and shovel-shaped. holes” for refuge, and the water retained by these holes helps to With their formidable size and powerful support many other aquatic animals jaws, alligators are intimidating animals to through the southern winter. encounter. However, your chances of being injured by an alligator are slim: you are far more likely to be injured while boating, water skiing, or scuba diving.