PRIVA TISA Tion, RURAL RAIL WA YS and COMMUNITY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Great Western Railway Ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway Ships from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

5/20/2011 Great Western Railway ships - Wikipedi… Great Western Railway ships From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Great Western Railway’s ships operated in Great Western Railway connection with the company's trains to provide services to (shipping services) Ireland, the Channel Islands and France.[1] Powers were granted by Act of Parliament for the Great Western Railway (GWR) to operate ships in 1871. The following year the company took over the ships operated by Ford and Jackson on the route between Wales and Ireland. Services were operated between Weymouth, the Channel Islands and France on the former Weymouth and Channel Islands Steam Packet Company routes. Smaller GWR vessels were also used as tenders at Plymouth and on ferry routes on the River Severn and River Dart. The railway also operated tugs and other craft at their docks in Wales and South West England. The Great Western Railway’s principal routes and docks Contents Predecessor Ford and Jackson Successor British Railways 1 History 2 Sea-going ships Founded 1871 2.1 A to G Defunct 1948 2.2 H to O Headquarters Milford/Fishguard, Wales 2.3 P to R 2.4 S Parent Great Western Railway 2.5 T to Z 3 River ferries 4 Tugs and work boats 4.1 A to M 4.2 N to Z 5 Colours 6 References History Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the GWR’s chief engineer, envisaged the railway linking London with the United States of America. He was responsible for designing three large ships, the SS Great Western (1837), SS Great Britain (1843; now preserved at Bristol), and SS Great Eastern (1858). -

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Saltash Floating Bridge Saltash Passage and D-Day, 6 June 1944

SALTASH PASSAGE altash Passage and nearby Little Ash were once part of Cornwall – although they have both always been Saltash Floating Bridge within the Devonshire parish of St Budeaux. For over 600 years there was an important ferry crossing here, The Royal Albert Bridge Devon born civil engineer James Meadows Rendel moved to Plymouth in the Sto Saltash. A major problem in taking the steam railway west from Plymouth and on into early 1820s. His Saltash Floating Bridge was Plymouth-built and entered service From 1851, and for 110 years, the Saltash Ferry was served by a powered floating bridge or chain ferry. Saltash Cornwall was crossing the River Tamar. In 1848, Isambard Kingdom Brunel in early 1833. The machinery was in the middle, with a deck either side for foot proposed a viaduct at Saltash, where the river is just 335 metres (1,100ft) wide. passengers, horses and livestock, or up to four carriages. Because of the strong Corporation held the ferry rights for much of that time. There were seven floating bridges in total and the last The final agreed design was for a wrought iron, bow string suspension bridge; current, the fixed chain and ferry crossed the river at an angle. Rendel’s Saltash ferry crossed here in October 1961. part arched bridge, part suspension bridge – with the roadway suspended from Ferry was pioneering but unreliable. It was withdrawn in months and the old The Saltash Viaduct is better known as the Royal Albert Bridge. It was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in two self-supporting tubular trusses. -

[Cornwall. J Cam Borne. 724 [Post Office

[CORNWALL. J CAM BORNE. 724 [POST OFFICE vu~~ · William, farmer, St. Ann's Rowe George, mine agent Gunnislake. ; & at Hatches Rowe William Henry, grocer Crocker Emanuel, Flora villa ' shoe maker, Albaston Scown Mary (Mrs.), Metherill inn, Haime Rev. Herbert Wesley [Wes- T agent to Messrs. Metherill leyan], Wesley villa Vivian & Sons, coal merchants Searle J ames Border, chemist & drug- Knight Thomas, Plushpark cottage Hall Patience (Mrs.)~ dairyman gist; & at Gunnislake L' Estrange W m.Carleton,Flora vil.Xo.2 Hambly Richard, shopkeeper SeccombeChas.shopkeeper,Chilsworthy Parker Rev. G. [curatel Harris S. Carpenters'.Arms, Metherill Seccombe Jhn. miningagnt.Chilswrthy Ramsey Edward, Heath cottage Hearne James, blacksmith, Cox's park Sims Nicholas, farmer, Oakenhays Sleman John, Rockview Hillman Nathaniel Thomas, cooper Skinner John, miller, Harrowbarrow coMMERCIAL. Hillman Richard, farmer, Cox's park Smale Richard, farmer, Albaston Abbot James, tailor Hole William John, grocer Snow ~~iam, miller, Cold Harbour Adamson -, Cornish inn Hooper Richard, saddler, Albaston Sowton John, grocer Andrews John, shopkeeper Borne John, farmer, Park SfJarrow Benjamin, lime burner (Ed- Baker Edmund, ironmonger Hunn Nicholas, carpenter, Metherill mundSimmonds,agent), Cothelequay Barkd)Thomas, shopkeeper Hutchings Mary Ann (Mrs.), grocer Spear Elizh. (Mrs.), farmer, Metherill , Bickle William Aaron, butcher lsbell Wm.blacksmith,E. Harrowbarrw Spear John, farmer, Metherill Bolr SiQl()ll', shopkeeper Jago Jhn. Truscott, wheelwrt. Albaston Speare James, farmer,•-Latchley Draund John, linen draper J ames Hanibal, shopkpr. St.Ann's chap! Speare John, farmer, Latchley Bnry An?~, relieving officer Jeffery Thomas, grocer & mason Stenlake James, farmer, Chilsworthy Bray Thomas, carrier Jeffery Wm. farmr. We. Harrowbarrow Stenlake John, farmer, Chilsworthy Buckingham MarySarab (Mrs.), sbop- Johns Bennett, farmer, Sandhill Stephens Edward, shopkeeper, Latchley keeper & postmistress Jolls Mary Ann (Mrs.), lodging house Stepbens William, farmer, Latchley Cock John, carpenter Jones Thos. -

View Fleet List (1919-2021)

FLEET LIST (1919-2021) Fleet Seating Into Fleet Reg No:Chassis: Make & Model Chassis No: Body: Make & Type New Withdrawn Notes No: & Format if used 1 PW 1558 Ford T Economy, Lowestoft B14F -/19 - 11/28 Burnt out 2 CT 6489 Chevrolet 29262 Andrews B14 05/24 - 11/28 Burnt out 3 CT 7421 Lancia 4947 Delaine 26 06/25 - 11/28 Burnt out 4 CT 8216 W&G. L 2553 W&G B26F 06/26 - 09/32 Broken up 01/36 5 CT 9025 W&G 3261 Hall Lewis B26F 05/27 - 06/36 Chassis to shed in yard, Broken Up : Body Broken up 06/39 6 CY 8972 W&G 5001 - 28 -/28 11/28 -/29 On loan from and returned to W&G 7 ? W&G - - 26 ? 11/28 -/29 On loan from operator near Cadnam : To W&G Southampton 8 ? Reo - - 26 ? 11/28 -/29 On loan from CH Skinner, Spalding (Dealer) 18 CT 9869 W&G 2639 Hall Lewis B32F 07/28 - 02/52 Broken up 11/55 9 TL 364 Gilford 166SD 10668 Clarke, Scunthorpe B26F 04/29 - by/40 To Canham, Whittlesey 10 TL 565 Chevrolet LQ 54366 Bracebridge B14F 06/29 - -/30 To Brown, Caister 19 TL 1066 Leyland TS2 60895 Duple C31F 03/30 - 03/55 Rebodied by Holbrook C37F in 1939. Scrapped on site 03/55 17 TL 1316 Reo Pullman 1528 Bracebridge B20F 07/30 - 12/48 To shed in Yard 11 TL 2224 Leyland TS4 202 Burlingham B32F 03/32 - 08/40 Requistioned by War Dept. Bombed in 1943 20 TL 2965 Leyland TS6 2982 Burlingham C37F 07/33 - 06/53 Requistioned by War Dept and returned. -

Antique Bottles, Pot Lids& Advertising

October 4 & 5 catalogue:Layout 1 4/9/14 10:09 Page 1 Saturday 4 Oct 500+ lot Unreserved Auction BBRAUCTIONS Sunday 5 Oct MAJOR Show & Auction BBR’s 2014 Autumn Extravaganza week-end & Antique “... the Yanks are coming...” Bottles, Pot Lids & Advertising Ginger beers Tins Poisons Old cabinets Pub Jugs Salt Glaze Pot lids Minerals Pharmacy Inks Stoneware Black glass Whisky jugs Kitchenalia Early Doulton Cream pots Guinness Enamel signs October 4 & 5 catalogue:Layout 1 4/9/14 10:09 Page 2 BBRAUCTIONS BBR’s 2014 Autumn Extravaganza Saturday 4 October Unreserved Auction, Blg 21 Sunday 5 October BIG Show & Auction all in Blg 21 SATURDAY 500+ lot Auction Doors open 9am Sale 11am SUNDAY Show & Auction E.E. 8.30am Auction viewing 9am Sale 11am Postal, tel. (book lines early!) & fax bidding facility. Low cost after sale p & p worldwide Buyers premium 15%, plus vat - only on premium Sunday auction held beside BBR’s Autumn Extravaganza for which there is an admission charge FREE PARKING ACCOMMODATION: see list to rear of catalogue, or email BBR Viewing stops approx. 10 mins. before sale start @ 11am. Sunday bidders must register early, to obtain a bidding number. All items sold ‘as seen’ on sale day. - all must view & inspect goods beforehand & accept BBR’s Terms & Conditions (rear of cat/ print outs on viewing tables). Payment & collection can take place any time during the sale. BBR, Elsecar Heritage Centre, Nr Barnsley, S Yorks., S74 8HJ tel: 01226 745156 fax: 01226 361561 email: [email protected] www.onlinebbr.com Collector provenance stickers BBR is selling a number of large collections all bearing a ‘provenance’ sticker. -

BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:14 Page 1

BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:14 Page 1 BRITAIN‘S LEADING HISTORICAL RAILWAY JOURNAL VOLUME 22 • NUMBER 1 • JANUARY 2008 • £3.60 IN THIS ISSUE 150 YEARS OF THE SOMERSET & DORSET RAILWAY GWR RAILCARS IN COLOUR THE NORTH CORNWALL LINE THE FURNESS LINE IN COLOUR PENDRAGON BRITISH ENGLISH-ELECTRIC MANUFACTURERS PUBLISHING THE GWR EXPRESS 4-4-0 CLASSES THE COMPREHENSIVE VOICE OF RAILWAY HISTORY BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 15:59 Page 64 THE COMPREHENSIVE VOICE OF RAILWAY HISTORY END OF THE YEAR AT ASHBY JUNCTION A light snowfall lends a crisp feel to this view at Ashby Junction, just north of Nuneaton, on 29th December 1962. Two LMS 4-6-0s, Class 5 No.45058 piloting ‘Jubilee’ No.45592 Indore, whisk the late-running Heysham–London Euston ‘Ulster Express’ past the signal box in a flurry of steam, while 8F 2-8-0 No.48349 waits to bring a freight off the Ashby & Nuneaton line. As the year draws to a close, steam can ponder upon the inexorable march south of the West Coast Main Line electrification. (Tommy Tomalin) PENDRAGON PUBLISHING www.pendragonpublishing.co.uk BACKTRACK 22-1 2008:Layout 1 21/11/07 14:17 Page 4 SOUTHERN GONE WEST A busy scene at Halwill Junction on 31st August 1964. BR Class 4 4-6-0 No.75022 is approaching with the 8.48am from Padstow, THE NORTH CORNWALL while Class 4 2-6-4T No.80037 waits to shape of the ancient Bodmin & Wadebridge proceed with the 10.00 Okehampton–Padstow. -

Replacing Amtrak: Privatization, Regionalization, and Liquidation

P o l i c y S t u d y N o . 2 3 5 , O c t o b e r 1 9 9 7 RReeppllaacciinngg AAmmttrraakk:: A Blueprint for Sustainable Passenger Rail Service by Joseph Vranich EXECUTIVE SUMMARY mtrak is a failed national experiment. By its own admission, Amtrak is headed for bankruptcy unless Washington provides another multi-billion-dollar bail-out. Another federal rescue is A unjustified considering that federal and state subsidies to Amtrak since its inception in 1971 are nearing $22.5 billion, an amount out of proportion to Amtrak’s usefulness in most of the nation. The federal government does not run a national airline. It doesn’t operate a national bus company. There’s no justification for a national railroad passenger operation. America needs passenger trains in selected areas, but doesn’t need Amtrak’s antiquated route system, poor service, unreasonable operating deficits, and capital investment program with low rates of return. Amtrak’s failures result in part because it is a public monopoly—the very type of organization least able to innovate. This study reveals an Amtrak credibility crisis in the way it reports ridership figures, glosses over dwindling market share, understates subsidies, issues misleading cost-recovery claims, offers doubtful promises regarding high-speed rail, lacks proper authority for the freight business it recently launched, and misrepresents privatization as its applies to Amtrak. It’s time to liquidate Amtrak, privatize and regionalize parts of it, permit alternative operators to transform some long-distance trains into land-cruise trains, and stop service on hopeless routes. -

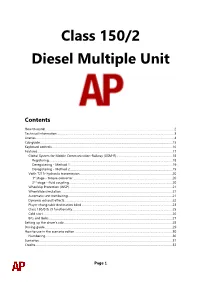

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

William Webber (Note 1)

Webber Families originating in the Middle Section of the Taw Valley in the late 18th and 19th centuries, (mainly Chulmleigh, Chawleigh and Burrington, plus some neighbouring parishes with close links to them). Compiled by David Knapman © April 2014 To the reader: If you find something here which is of interest, you are welcome to quote from this document, or to make reasonable use of it for your own personal researches, but it would be appreciated if you would acknowledge the source where appropriate. Please be aware that this is a ‘live’ document, and is sure to contain mistakes. As and when I find or receive better information I will add to and/or correct it. This raises two points: if you find an error or omission, please let me know; and if you propose to use the information contained here at some future point, it may be worth checking back with me to see whether the information you propose to use has subsequently been corrected or improved. Although I do not generally propose to extend the narrative past 1900, I would be very pleased to attach a note to any of the families to report that a family of 21st century Webbers can be traced back to any of the families identified here. So if you find your ancestors, and the Webber surname survives via their / your family, please let me know. David Knapman, April 2014 (david.j.knapman @ btinternet.com) Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Families from Chulmleigh and Around 4 3 Families from Chawleigh 81 4 Families from Burrington 104 Chapter 1: Introduction Purpose and main sources The focus of this document is on the existence and survival of the Webber surname. -

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain's Rail Network

2-Stroke Diesels on Britain’s Rail Network Rodger Bradley Back in the 1950s, when British Railways was beginning work on the “Modernisation & Re-Equipment Programme” – effectively the changeover from steam to diesel and electric traction – the focus in the diesel world was mainly between high and medium speed engines. On top of which, there was a practical argument to support hydraulic versus electric transmission technology – for main line use, mechanical transmission was never a serious contender. The first main line diesels had appeared in the very last days before nationalisation, and the choice of prime mover was shaped to a great extent by the experience of private industry, and English Electric in particular. The railway workshops had little or no experience in The prototype main-line 2-stroke powered loco for the field, and the better known steam locomotive express passenger service on BR was never repeated. builders had had some less than successful attempts to Photo: Thomas's Pics CC BY 2.0, offer examples of the new diesel locomotives. That https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50662416 said, some of the smaller companies, who had worked with the railways pre-WW2 to supply small shunting Pilot Scheme & Modernisation In the first flush of enthusiasm for the new technology, British Railways announced three types of diesel locomotive to be trialled for main line use; diesel shunters had already been in use for a number of years. The shunting types were a mix of electric and mechanical transmission, paired with 4-stroke diesel engines, and not surprisingly the first main line designs included electric transmission and 4-stroke, medium speed engines.