Out of Many, One: Glimpses of the USA by Charles and Ray Eames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-30-1986 The design and construction of furniture for mass production Kevin Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stark, Kevin, "The design and construction of furniture for mass production" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OP TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production By Kevin J. Stark May, 1986 APPROVALS Adviser: Mr. William Keyser/ William Keyser Date: 7 I Associate Adviser: Mr. Douglas Sigler/ Date: Douglas Sigler Associate Adviser: Mr. Craig McArt/ Craig McArt Date: U3{)/8:£ ----~-~~~~7~~------------- Special Assistant to the h I Dean for Graduate Affairs:Mr. Phillip Bornarth/ P i ip Bornarth Da t e : t ;{ ~fft, :..:..=.....:......::....:.:..-=-=-=...i~:...::....:..:.=-=..:..:..!..._------!..... ___ -------7~'tf~~---------- Dean, College of Fine & Applied Arts: Dr. Robert H. Johnston/ Robert H. Johnston Ph.D. Date: ------------------------------ I, Kevin J. Stark , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Date : ____5__ ?_O_-=B::;..... 0.:.......-_____ CONTENTS Thesis Proposal i CHAPTER I - Introduction 1 CHAPTER II - An Investigation Into The Design and Construction Process Side Chair 2 Executive Desk 12 Conference Table 18 Shelving Unit 25 CHAPTER III - A Perspective On Techniques Used In Industrial Furniture Design Wood 33 Metals 37 Plastics 41 CHAPTER IV - Conclusion 47 CHAPTER V - Footnotes 49 CHAPTER VI - Bibliography 50 ILLUSTRATIONS Page I. -

Oral History of Edward Charles Bassett

ORAL HISTORY OF EDWARD CHARLES BASSETT Interviewed by Betty J. Blum Compiled under the auspices of the Chicago Architects Oral History Project The Ernest R. Graham Study Center for Architectural Drawings Department of Architecture The Art Institute of Chicago Copyright © 1992 Revised Edition Copyright © 2006 The Art Institute of Chicago This manuscript is hereby made available to the public for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publication, are reserved to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries of The Art Institute of Chicago. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of The Art Institute of Chicago. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iv Preface to Revised Edition v Outline of Topics vi Oral History 1 Selected References 149 Curriculum Vitae 150 Index of Names and Buildings 151 iii PREFACE On January 30, 31, and February 1, 1989, I met with Edward Charles Bassett in his home in Mill Valley, California, to record his memoirs. Retired now, "Chuck" has been the head of design of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill's San Francisco office from 1955-1981. Those twenty-six years were a time of unprecedented growth and change to which Chuck not only bore witness but helped shape. Chuck Bassett was one of the SOM triumvirate of the postwar years: he was the West Coast counterpart of Gordon Bunshaft in New York and William Hartmann in Chicago. In 1988 the California Council of the American Institute of Architects awarded SOM, San Francisco, a 42-year award for "...the genuine commitment that the firm has had to its city, to the profession and to both art and the business of architecture." Although Chuck prefers to be known as a team player, his personal contribution to this achievement is unmistakable in the context of urban San Francisco since 1955. -

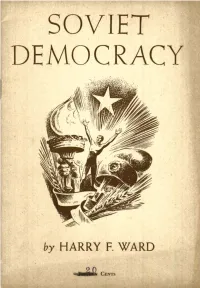

Soviet Democracy

SOVIET DEMOCRACY by Harry E Ward SOVIET RUSSIA TODAY New York 1947 NOTE ON THE AUTHOR Dr. Harry F. Ward is Professor Emeritus of Christian Ethics at Union Theological Seminary. He has spent considerable time in the Soviet Union and has writ- ten and lectured extensively on the Soviet Union. His books include In Place af Profit, Democracy and Social Change and The Soviet Spirit. The cover is by Lynd Ward, son of the author, dis- tinguished American artist who is known for his novels in pictures and for his book illustrations. - i 5.1 12.$fiW Photos, excem where otherwise in icated v cour- tesy of the ~xhibitsDepartment of the ~atiohai~oun- cil of American-Soviet Friendship. A PUB1,ICATION OF SOVIET RUSSIA TODAY 114 East ~2ndSt., New York i6, N. Y. PRINTED IN THE U.S.A. 209 CHAPTER I THE ECONOMIC BASE URING 1945 and 1946 the Soviet press carried on an extensive discussion of Soviet democracy-what it is D. and how it works. This discussion began as an edu- cational preparation for the election of the Supreme So- viet. It continued in response to much talk here about "dif- ferent ideas of democracy" that arose from disagreements in the United Nations and in the occupation of enemy coun- tries. Soviet writers point out that underneath such differ- ences over procedures is the historic fact that theirs is a so- cialist democracy. This, they tell their readers, makes it a higher form than capitalist democracy. They mean higher in the ongoing of the democratic process not merely as a form of government, but a cooperative way of life through which more and more of the people of the earth, by increas- ing their control over both nature and human society, emancipate themselves from famine, pestilence and war, as well as from tyranny. -

Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames in the Organic Design Competition, Moma, 1941

26 TRABAJANDO CON MAQUETAS: EERO SAARINEN Y CHARLES EAMES EN LA ORGANIC DESIGN COMPETITION, MoMA, 1941 WORKING WITH SCALE MODELS: EERO SAARINEN AND CHARLES EAMES IN THE ORGANIC DESIGN COMPETITION, MoMA, 1941 Carlos Montes Serrano, Noelia Galván Desvaux, Álvaro Moral García doi: 10.4995/ega.2019.12684 El presente artículo estudia los This article looks at the background antecedentes de la primera of the first exhibition given over exposición dedicada al diseño de to modern furniture design in mobiliario moderno en América America organized at the Museum organizada en el MoMA en 1941. Se of Modern Art in 1941. It becomes constata que la gran mayoría de los clear that the great majority of diseños premiados en el concurso the designs awarded prizes in the previo a la exposición fueron competition prior to the exhibition elaborados por jóvenes arquitectos, were produced by young architects. ya que eran los únicos que estaban This was because they were the al día de las tendencias modernas only people who were up-to-date derivadas de la Bauhaus o del with modern trends emanating diseño escandinavo. Tanto el from the Bauhaus or Scandinavian organizador, Eliot Noyes, como design. Both the organizer, Eliot los premiados, Eero Saarinen y Noyes, and the prize-winners, Charles Eames, despuntaron tras la Eero Saarinen and Charles Eames, guerra mundial como diseñadores became prominent after the Second de sobresaliente trayectoria World War as designers with profesional. Por último, resulta de outstanding professional careers. interés comprobar el papel que Finally, it is of interest to note the llegaron a alcanzar los prototipos y part played by prototypes and scale maquetas a escala en los procesos models in the processes of furniture de diseño de mobiliario. -

Exploring the Complex Political Ideology Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2006 Major Subject: English RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, William Bedford Clark Committee Members, Clinton J. Machann Marco A. Portales David Vaught Head of Department, Paul A. Parrish August 2006 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Recovering Carl Sandburg: Politics, Prose, and Poetry After 1920. (August 2006) Evert Villarreal, B.A., The University of Texas-Pan American; M.A., The University of Texas-Pan American Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. William Bedford Clark Chapter I of this study is an attempt to articulate and understand the factors that have contributed to Carl Sandburg’s declining trajectory, which has led to a reputation that has diminished significantly in the twentieth century. I note that from the outset of his long career of publication – running from 1904 to 1963 – Sandburg was a literary outsider despite (and sometimes because of) his great public popularity though he enjoyed a national reputation from the early 1920s onward. Chapter II clarifies how Carl Sandburg, in various ways, was attempting to re- invent or re-construct American literature. -

The Novosti Press Agency Photograph Collection 21 Mirror Images: the Novosti Press Agency Photograph Collection*

The Novosti Press Agency Photograph Collection 21 Mirror Images: The Novosti Press Agency Photograph Collection* JENNIFER ANDERSON RÉSUMÉ La collection de photographies de la Novosti Press Agency, conservée aux Special Collections and Archives de l’Université Carleton, est une ressource rare et fascinante. Les 70 000 photographies et les textes d’accompagnement, qui datent de 1917 à 1991, appartenaient autrefois au Bureau de la Soviet Novosti Press Agency (APN), situé sur la rue Charlotte à Ottawa, mais le personnel de la bibliothèque Carleton a dû récupérer ce matériel rapidement vers la fin de l’année 1991 avec la dissolution de l’Union soviétique et la fermeture du Bureau à Ottawa. Fondé en partie pour encourager les Occidentaux, en particulier les Canadiens, à voir l’URSS d’un meilleur œil, l’APN d’Ottawa distribuait ces photographies et ces communiqués de presse aux médias, aux or ganisations et aux individus à travers le Canada. La collec- tion offre aux historiens un aperçu de la construction de l’image que se donnait l’Union soviétique, les points de vues soviétiques of ficiels sur les relations interna- tionales pendant la Guerre froide et les ef forts pour adoucir les opinions anti-sovié- tiques au Canada. Dans son texte « Mirror Images », Jennifer Anderson soutient que la collection mérite d’être mieux connue des historiens de la Guerre froide au Canada et des historiens qui s’intéressent aux relations internationales et que le grand public pourrait aussi être intéressé par une exposition conçue autour de l’idéologie, de la perception et de la construction de l’identité pendant la Guerre froide. -

10 the Pharos/Summer 2012 Anton Chekhov in Medical School— and After

10 The Pharos/Summer 2012 Anton Chekhov in medical school— and after An artist’s flair is sometimes worth a scientist’s brains – Anton Chekhov Leon Morgenstern, MD The author (AΩA, New York University, 1943) is Emeritus it significantly enlarged the scope of my observations and Director of the Center for Health Care Ethics and Emeritus enriched me with knowledge whose true worth to a writer Director of Surgery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los can be evaluated only by somebody who is himself a doctor; Angeles, and Emeritus Professor of Surgery at the David it has also provided me with a sense of direction, and I am Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. sure that my closeness to medicine has also enabled me to avoid many mistakes.1p425 t is often overlooked, and sometimes forgotten, that Anton Chekhov, the noted Russian writer of short stories and plays, Medical school was a pivotal juncture in the delicate balance Iwas also a doctor. He was one of the principal authors in between the two careers. It made him into the doctor he was. what has been called the Golden Age of Russian Literature It helped him reach the goal of becoming the writer he was in the mid- and late-nineteenth century, along with Fyodor to be. Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and Ivan Turgenev. Chekhov was born in Taganrog, a port town founded by In 1879 at the age of nineteen, Anton Chekhov enrolled in Peter the Great on the Sea of Azov in Southern Russia. His the medical school of Moscow University. -

Chronology of the Department of Photography

f^ The Museum otI nModer n Art May 196k 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart CHRONOLOGY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Department of Photography was established in lQl+0 to function as a focal center where the esthetic problems of photography can be evaluated, where the artist who has chosen the camera as his medium can find guidance by example and encouragement and where the vast amateur public can study both the classics and the most recent and significant developments of photography. 1929 Wi® Museum of Modern Art founded 1952 Photography first exhibited in MURALS BY AMERICAN PAINTERS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS; mural of George Washington Bridge by Edward Steichen included. Accompany ing catalog edited by Julian Levy. 1953 First photographs acquired for Collection WALKER EVANS: PHOTOGRAPHS OF 19th CENTURY HOUSES - first one-man photogra phy show. 1937 First survey exhibition and catalog PHOTOGRAPHY: I839-I937, by Beaumont NewhalU 1958 WALKER EVANS: AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHS. Accompanying publication has intro duction by Lincoln Firstein. Photography: A Short Critical History by Beaumont Newhall published (reprint of 1937 publication). Sixty photographs sent to the Musee du Jeu de Paume, Paris, as part of exhibition TE.3E CENTURIES OF AMERICAN ART organized and selected by The Museum of Modern Art. 1939 Museum opens building at 11 West 53rd Street. Section of Art in Our Tims (10th Anniversary Exhibition) is devoted to SEVEN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHERS. Photographs included in an exhibition of paintings and drawings of Charles Sheeler and in accompanying catalog. 19^0 Department of Photography is established with David McAlpin, Trustee Chairman, Beaumont Newhall, Curator. -

“THE FAMILY of MAN”: a VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION of HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay

“THE FAMILY OF MAN”: A VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay “The Family of Man,” the exhibition curated by Edward Steichen in 1955, was a landmark event in the history of photography and human rights.1 It was visited by mil- lions of spectators around the world and was an object of critique — of which Roland Barthes was the lead- ing voice — that has become paradigmatic in the fields of visual culture and critical theory.2 A contemporary revi- sion of “The Family of Man” should start with question- ing Barthes’s precise and compelling observations and his role as a viewer. He dismissed the photographic material and what he claimed to be mainly invisible ideas — astonishingly so, considering that the hidden ideology he ascribed to the exhibition was similar to Steichen’s explicit 1 See the exhibition catalog, Edward Steichen, The Family of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955). 2 Following a first wave of critique of the exhibition, influenced mainly by Barthes’s 1956 essay “The Great Family of Man,” a second wave of writers began to be interested in the exhibition and its role and modes of reception during the ten years of its world tour. See, for example, Eric J. Sandeen, “The Family of Man 1955–2001,” in “The Family of Man,” 1955–2001: Humanism and Postmodernism; A Reappraisal of the Photo Exhibition by Edward Steichen, eds. Jean Back and Viktoria Schmidt- Linsenhoff (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 2005); and Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). -

The Family of Man in the 21St Century Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition

THE FAMILY OF MAN IN THE 21ST CENTURY Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition Liège Clervaux Namur/Bruxelles Trier International Conference THE FAMILY OF MAN 19-20 June 2015 STEICHEN COLLECTIONS Clervaux Castle Clervaux Castle, Clervaux, Luxembourg Luxembourg B.P. 32 L-9701 Clervaux Tel. : + 352 92 96 57 Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time & Life © Getty Images Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time [email protected] Dudelange www.steichencollections.lu Thionville/Metz www.steichencollections.lu THE FAMILY OF MAN Conference Program IN THE 21ST CENTURY FRIDAY 19.06.2015 SATURDAY 20.06.2015 10:00 10:00-10:45 Conference Welcome Kerstin Schmidt (Catholic University Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt, Germany) 10:15-12:00 Places of the Human Condition: Aesthetics and Jean Back, Anke Reitz (CNA, Luxembourg) Philosophy of Place in Steichen’s The Family of Man Guided Tour of the Exhibition The Family of Man With more than ten million viewers across the The conference wants to reassess and discuss 10:45-11:30 globe and more than five million copies of its the exhibition’s appeal and message, launched 12:00-14:00 Lunch Break Eric Sandeen (University of Wyoming, catalogue sold, “The Family of Man” is one of against the backdrop of Cold War threat of Laramie, WY, USA) the most successful, influential, and written atomic annihilation. It also wants to indicate 14:00-14:30 The Family of Man at Home about photography exhibitions of all time. It new ways in which the exhibition, as an artis- Bob Krieps (Director General 11:30-11:45 Short Coffee Break introduced the art of photography to the gen- tic response to a historical moment of crisis, of the Ministry of Culture) Welcoming Remarks eral public, one critic noted, “like no other pho- can remain relevant in the context of 21st-cen- 11:45-12:30 tographic event had ever done.” At the same tury challenges. -

John and Marilyn Neuhart Papers, 1916-2011; Bulk, 1957-2000

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8sj1mft No online items John and Marilyn Neuhart papers, 1916-2011; Bulk, 1957-2000 Finding aid prepared by Saundarya Thapa, 2013; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. The processing of this collection was generously supported by Arcadia. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA, 90095-1575 (310) 825-4988 [email protected] © 2013 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. John and Marilyn Neuhart papers, 1891 1 1916-2011; Bulk, 1957-2000 Title: John and Marilyn Neuhart papers Collection number: 1891 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 40.0 linear ft.(57 document boxes, 3 record cartons, 10 flat boxes, 4 telescope boxes, 1 map folder) Date (bulk): Bulk, 1957-2000 Date (inclusive): 1916-2011 Abstract: John and Marilyn Neuhart were graphic and exhibition designers and UCLA professors who also worked at the Eames Design Office in Los Angeles. This collection includes research files for their books on the Eames Office, material documenting the design and organization process for Connections, an exhibition on the Eames Office which was held at UCLA in 1976, ephemera relating to the work of the Eames Office as well as the Neuhart’s own design firm, Neuhart Donges Neuhart and a large volume of research files and ephemera that was assembled in preparation for a proposed book on the American designer, Alexander Girard. Language of Materials: Materials are in English. Physical Location: Stored off-site at SRLF. -

Deploying the Dead: Combat Photography, Death and the Second World War in the USA and the Soviet Union

KEVIN FOSTER Deploying the Dead: Combat Photography, Death and the Second World War in the USA and the Soviet Union s Susan Sontag has noted, ‘Ever since cameras were invented in 1839, photography has kept company with death’ (Sontag, 2003: 24). It has done so, principally, by taking its place on the world’s battlefields and, from the AUS Civil War onwards, bringing to the public graphic images of war’s ultimate truth. The camera’s unflinching witness to death helped establish photography’s authority as an apparently unimpeachable record of events. ‘A photograph’, Sontag observes, ‘passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened’ (Sontag, 1977: 5). Yet the ‘truth’ of any photo is only ever conditional: ‘the photographic image … cannot be simply a transparency of something that happened. It is always the image that someone chose; to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude’ (Sontag, 2003: 46). Photographers often worked, and continue to work, under close editorial direction with a detailed brief to collect specific images from designated areas in prescribed forms. The photographs they take are ‘Crafted through a maze of practices and standards, both explicit and implicit’ overseen by ‘photographers, photographic editors, news editors and journalists’ who collectively determine ‘how war can be reduced to a photograph’. The resulting images, Barbie Zelizer argues, ‘reflect what the camera sees by projecting onto that vision a set of broader assumptions about how the world works’ (Zelizer, 2004: 115). In this context it is clear that the photographic truth is less an elusive ideal than a consciously crafted product – it is manufactured, not discovered or revealed.