Trolley— New Orleans Robert Frank Trolley—New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Street Seen Teachers Guide

JAN 30–APR 25, 2010 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL GESTURE IN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE CONTENTS 2 Using This Teachers Guide 3 A Walk through Street Seen 10 Vocabulary 11 Cross-Curricular Activities 15 Lesson Plan 18 Further Resources cover image credit Ted Croner, Untitled (Pedestrian on Snowy Street), 1947–48. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. ©Ted Croner Estate prepared by Chelsea Kelly, School & Teacher Programs Manager, Milwaukee Art Museum STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 1 USING THIS TEACHERS GUIDE This guide, intended for teachers of grades 6–12, is meant to provide background information about and classroom implementation ideas inspired by Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959, on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through April 25, 2010. In addition to an introductory walk-through of the exhibition, this guide includes useful vocabulary, discussion questions to use in the galleries and in the classroom, lesson ideas for cross-curricular activities, a complete lesson plan, and further resources. Learn more about the exhibition at mam.org/streetseen. Let us know what you think of this guide and how you use it. Email us at [email protected]. STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 2 A WALK THROUGH STREET SEEN This introduction follows the organization of the exhibition; use it and the accompanying discussion questions as a guide when you walk through Street Seen with your students. Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 showcases the work of six American artists whose work was directly influenced by World War II. -

Street Photography

Columbia College Chicago Framing ideas street Photography Curriculum guide Aimed at middle school and high school and college age students, this resource is aligned with Illinois Learning Standards for English Language Arts Incorporating the Common Core and contains questions for looking and discussion, information on the artists and artistic traditions and classroom activities. A corresponding image set can be found HERE. The MoCP is a nonprofit, tax- exempt organization accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. The Museum is generously supported by Columbia College Chicago, the MoCP antonio Perez A Man Dressed as Charro on his Horse Waits for his Take-Out Food before the Start of the Annual Cinco de Mayo Parade Down Advisory Committee, individuals, Cermak in Chicago, September 2000. Museum purchase private and corporate foundations, and government agencies including the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency. The museum’s education work is additionally supported by After School Matters, the Lloyd A. Fry Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Special funding for this guide was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art. 1 street Photography That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and the music comes out from a jukebox or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured in tremendous photographs taken as he traveled on the road around practically all forty-eight states in an old used car…Long shot of night road arrowing forlorn into immensities and flat of impossible-to- believe America in New Mexico under the prisoner’s moon… -Jack Kerouac, (from the introduction Robert Frank’s book The Americans) robert Frank robert Frank San Francisco, 1956 Political Rally, Chicago, 1956 Gift of Mr. -

America Through Street Photography

From the Instructor Sarah wrote this piece for my section of the Genre and Audience WR X cluster. Students had undertaken semester-long research projects and, in the final assignment for the course, were asked to reimagine their academic arguments for a public audience. Deciding to write in the style of The New Republic, which is, in the publication’s own words, “tailored for smart, curi- ous, socially aware readers.” Sarah’s focus on street photography brings her research on classic American images to a non-expert audience with diverse professional and disciplinary perspectives, appealing to their interests in history and the arts while tapping into contemporary culture. — Gwen Kordonowy WR 150: The American Road 135 From the Writer When I enrolled in an experimental writing class entitled “The American Road,” I assumed that the semester would be filled with discussions about the physical American road, its attractions, and its place in American history. While the physical road was an important subject in the class, I learned that this “American Road” was expansive beyond its physical limi- tations, able to encompass topics as broad and abstract as social progress, popular television shows, and, in my case, photography. I ultimately chose to investigate the works of two American street photographers, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, whose approaches to photography reveal much about life in America and what it means to be an American. While both photographers frequently feature the road in their pictures, I chose to focus more on the people and culture found alongside it and how they represent America. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

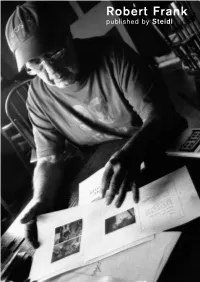

Robert Frank Published by Steidl

Robert Frank published by Steidl The Robert Frank Project “The Robert Frank Project” is an ambitious long term publishing programme which encompasses Robert Frank’s complete oeuvre – reprints of his classic books, reprints of some less well known small books, the publication of previously unseen projects, newly conceived bookworks, and his Complete Film Works in specially designed col- lector’s DVD sets. This ensures the legacy of this original and seminal artist and that Robert Frank’s work will be available and accessible for many years to come in a sche- me and to a standard that the artist himself has overseen. The publication of a new edition of “The Americans” on 15th May, 2008, the fiftieth anniversary of the first edition, is the fulcrum of The Robert Frank Project. It presages a major touring exhibition and accompanying catalogue from the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans”, which opens in January 2009. This brochure contains details of all the books and films which are currently available and those planned for the future. Gerhard Steidl Ute Eskildsen Laura Israel Publisher Editorial Adviser Film Works Adviser Delpire, 1958 Il Saggiatore, 1959 Grove Press, 1959 Delpire, 1993 Aperture, 1969 Christian, 1986 Scalo, 1993 Scalo, 2000 A Short Publishing History of “The Americans” by Monte Packham Robert Frank’s “The Americans” was first published in 1958 by Robert Delpire in Paris. It featured 83 of Frank’s photographs taken in America in 1955 and 1956, accompanied by writings in French about American political and social history selected by Alain Bosquet. -

Exploring the Complex Political Ideology Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M University RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2006 Major Subject: English RECOVERING CARL SANDBURG: POLITICS, PROSE, AND POETRY AFTER 1920 A Dissertation by EVERT VILLARREAL Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, William Bedford Clark Committee Members, Clinton J. Machann Marco A. Portales David Vaught Head of Department, Paul A. Parrish August 2006 Major Subject: English iii ABSTRACT Recovering Carl Sandburg: Politics, Prose, and Poetry After 1920. (August 2006) Evert Villarreal, B.A., The University of Texas-Pan American; M.A., The University of Texas-Pan American Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. William Bedford Clark Chapter I of this study is an attempt to articulate and understand the factors that have contributed to Carl Sandburg’s declining trajectory, which has led to a reputation that has diminished significantly in the twentieth century. I note that from the outset of his long career of publication – running from 1904 to 1963 – Sandburg was a literary outsider despite (and sometimes because of) his great public popularity though he enjoyed a national reputation from the early 1920s onward. Chapter II clarifies how Carl Sandburg, in various ways, was attempting to re- invent or re-construct American literature. -

Chronology of the Department of Photography

f^ The Museum otI nModer n Art May 196k 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart CHRONOLOGY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Department of Photography was established in lQl+0 to function as a focal center where the esthetic problems of photography can be evaluated, where the artist who has chosen the camera as his medium can find guidance by example and encouragement and where the vast amateur public can study both the classics and the most recent and significant developments of photography. 1929 Wi® Museum of Modern Art founded 1952 Photography first exhibited in MURALS BY AMERICAN PAINTERS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS; mural of George Washington Bridge by Edward Steichen included. Accompany ing catalog edited by Julian Levy. 1953 First photographs acquired for Collection WALKER EVANS: PHOTOGRAPHS OF 19th CENTURY HOUSES - first one-man photogra phy show. 1937 First survey exhibition and catalog PHOTOGRAPHY: I839-I937, by Beaumont NewhalU 1958 WALKER EVANS: AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHS. Accompanying publication has intro duction by Lincoln Firstein. Photography: A Short Critical History by Beaumont Newhall published (reprint of 1937 publication). Sixty photographs sent to the Musee du Jeu de Paume, Paris, as part of exhibition TE.3E CENTURIES OF AMERICAN ART organized and selected by The Museum of Modern Art. 1939 Museum opens building at 11 West 53rd Street. Section of Art in Our Tims (10th Anniversary Exhibition) is devoted to SEVEN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHERS. Photographs included in an exhibition of paintings and drawings of Charles Sheeler and in accompanying catalog. 19^0 Department of Photography is established with David McAlpin, Trustee Chairman, Beaumont Newhall, Curator. -

Robert Frank: the Americans Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ROBERT FRANK: THE AMERICANS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Frank,Jack Kerouac | 180 pages | 09 Jul 2009 | Steidl Publishers | 9783865215840 | English | Gottingen, Germany Robert Frank: The Americans PDF Book Tri-X film! On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the book's original publication 15 May , a new edition was published by Steidl. As he has done for every edition of The Americans , Frank changed the cropping of many of the photographs, usually including more information, and two slightly different photographs were used. Much of the criticism Frank faced was as well related to his photojournalistic style, wherein the immediacy of the hand-held camera introduced technical imperfections into the resulting images. Becker has written about The Americans as social analysis:. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Where are we going? It could seem as if Frank threw his Leica into the world and let it catch what it could, which happened, without fail, to be something exciting—fascination, pain, hilarity, disgust, longing. The show presented the work of Diane Arbus , Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand , who at the time were relatively little known younger-generation beneficiaries of Mr. Retrieved 5 July By Philip Gefter. Silverstein died in , Mr. Retrieved She is now known as Mary Frank. Over the next 10 years, Mr. Safe in neutral Switzerland from the Nazi threat looming across Europe, Robert Frank studied and apprenticed with graphic designers and photographers in Zurich, Basel and Geneva. Rizzo has been lighting the stages of Broadway for almost forty years. In , The Americans was finally published in the United States by Grove Press , with the text removed from the French edition due to concerns that it was too un-American in tone. -

“THE FAMILY of MAN”: a VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION of HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay

“THE FAMILY OF MAN”: A VISUAL UNIVERSAL DECLARATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS Ariella Azoulay “The Family of Man,” the exhibition curated by Edward Steichen in 1955, was a landmark event in the history of photography and human rights.1 It was visited by mil- lions of spectators around the world and was an object of critique — of which Roland Barthes was the lead- ing voice — that has become paradigmatic in the fields of visual culture and critical theory.2 A contemporary revi- sion of “The Family of Man” should start with question- ing Barthes’s precise and compelling observations and his role as a viewer. He dismissed the photographic material and what he claimed to be mainly invisible ideas — astonishingly so, considering that the hidden ideology he ascribed to the exhibition was similar to Steichen’s explicit 1 See the exhibition catalog, Edward Steichen, The Family of Man (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1955). 2 Following a first wave of critique of the exhibition, influenced mainly by Barthes’s 1956 essay “The Great Family of Man,” a second wave of writers began to be interested in the exhibition and its role and modes of reception during the ten years of its world tour. See, for example, Eric J. Sandeen, “The Family of Man 1955–2001,” in “The Family of Man,” 1955–2001: Humanism and Postmodernism; A Reappraisal of the Photo Exhibition by Edward Steichen, eds. Jean Back and Viktoria Schmidt- Linsenhoff (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 2005); and Blake Stimson, The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). -

Museum of Modern Art in New York Exhibits New Acquisitions in Photography

Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibits new acquisition... http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=6253... 11:09 am / 16 °C The First Art Newspaper on the Net Established in 1996 Austria Tuesday, May 14, 2013 Home Last Week Artists Galleries Museums Photographers Images Subscribe Comments Search Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibits new acquisitions in photography Lynn Hershman Leeson. Robertaʼs Construction Chart #2. 1976. Chromogenic color print, printed 2003, 22 15/16 x 29 5/8″ (58.3 x 75.3 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Modern Womenʼs Fund. © 2013 Lynn Hershman Leeson. NEW YORK, NY.- The Museum of Modern Art presents XL: 19 New Acquisitions in Photography, featuring a selection of major works—often multipart and serial images—by 19 contemporary artists, from May 10, 2013, to January 6, 2014. The exhibition features works, made between 1960 and the present, which have been acquired by the Department of Photography within the past five years and are on view at MoMA for the first time. The exhibition is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator; Sarah Meister, Curator; and Eva Respini, Associate Curator; with Katerina Stathopoulou, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. Filling five consecutive rooms in the third-floor Edward Steichen Photography Galleries, this installation includes a diverse set of works—from performative photographs to collage and appropriation to political and personal images made in the documentary tradition—that underscore the vitality of photographic experimentation today. The cross-generational group of 19 international artists consists of Yto Barrada, Phil Collins, Liz Deschenes, Stan Douglas, VALIE EXPORT, Robert Frank, Paul Graham, Leslie Hewitt, Birgit Jürgenssen, Jürgen Klauke, Běla Kolářová, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Dóra Maurer, Oscar Muñoz, Mariah Robertson, Allan Sekula, Stephen Shore, Taryn Simon, and Hank Willis Thomas. -

The Family of Man in the 21St Century Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition

THE FAMILY OF MAN IN THE 21ST CENTURY Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition Liège Clervaux Namur/Bruxelles Trier International Conference THE FAMILY OF MAN 19-20 June 2015 STEICHEN COLLECTIONS Clervaux Castle Clervaux Castle, Clervaux, Luxembourg Luxembourg B.P. 32 L-9701 Clervaux Tel. : + 352 92 96 57 Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time & Life © Getty Images Alfred Eisenstaedt, Time [email protected] Dudelange www.steichencollections.lu Thionville/Metz www.steichencollections.lu THE FAMILY OF MAN Conference Program IN THE 21ST CENTURY FRIDAY 19.06.2015 SATURDAY 20.06.2015 10:00 10:00-10:45 Conference Welcome Kerstin Schmidt (Catholic University Reassessing an Epochal Exhibition of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt, Germany) 10:15-12:00 Places of the Human Condition: Aesthetics and Jean Back, Anke Reitz (CNA, Luxembourg) Philosophy of Place in Steichen’s The Family of Man Guided Tour of the Exhibition The Family of Man With more than ten million viewers across the The conference wants to reassess and discuss 10:45-11:30 globe and more than five million copies of its the exhibition’s appeal and message, launched 12:00-14:00 Lunch Break Eric Sandeen (University of Wyoming, catalogue sold, “The Family of Man” is one of against the backdrop of Cold War threat of Laramie, WY, USA) the most successful, influential, and written atomic annihilation. It also wants to indicate 14:00-14:30 The Family of Man at Home about photography exhibitions of all time. It new ways in which the exhibition, as an artis- Bob Krieps (Director General 11:30-11:45 Short Coffee Break introduced the art of photography to the gen- tic response to a historical moment of crisis, of the Ministry of Culture) Welcoming Remarks eral public, one critic noted, “like no other pho- can remain relevant in the context of 21st-cen- 11:45-12:30 tographic event had ever done.” At the same tury challenges.