Street Photography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friedlander Dog's Best Friend PR March 2019

Andrew Smith Gallery Arizona, LLC. Masterpieces of Photography LEE FRIEDLANDER SHOW TITLE: Dog’s Best Friend Dates: April 27 - June 15, 2019 Artist’s Reception: DATE/TIME: Saturday April 27, 2019 2-4 p.m. “I think dogs are happy because people feed them fancy food, treat them nicely, pedicure and wash them, take them into their homes.” Lee Friedlander Andrew Smith Gallery, in its new location at 439 N. 6th Ave., Suite 179, Tucson, Arizona 85705, opens an exhibit by the eminent American photographer Lee Friedlander. The exhibit, Dog’s Best Friend, contains 18 prints of dogs and their owners, one of Friedlander’s ongoing “pet projects.” Lee and Maria Friedlander will attend the opening on Saturday, April 27, 2019 from 2 to 4 p.m., where the public is invited to visit with America’s most celebrated photographer and view “the dogs.” The exhibit continues through June 15, 2019. Lee Friedlander is one of America’s legendary photographers. Now in his eighties, he still photographs and makes his own prints in the darkroom as he has been doing for 60 years. In the 1950s he began documenting what he called “the American social landscape,” making pictures that showed how the camera sees reality (different from how the eye sees). In his layered compositions, what are normally understood to be separate objects; buildings, window displays, people, cars, etc., are perpetually interacting with reflective, opaque and transparent surfaces that distort, fragment and bring about surprising, often humorous conjunctions. Friedlander has been photographing virtually non-stop these many decades, expanding the vocabulary of such traditional artistic themes as family, nudes, gardens, trees, self-portraits, landscapes, cityscapes, laborers, artists, jazz musicians, cars, graffiti, statues, parks, advertising signs, and animals. -

Pressemappe American Photography

Exhibition Facts Duration 24 August – 28 November 2021 Virtual Opening 23. August 2021 | 6.30 PM | on Facebook-Live & YouTube Venue Bastion Hall Curator Walter Moser Co-Curator Anna Hanreich Works ca. 180 Catalogue Available for EUR EUR 29,90 (English & German) onsite at the Museum Shop as well as via www.albertina.at Contact Albertinaplatz 1 | 1010 Vienna T +43 (01) 534 83 0 [email protected] www.albertina.at Opening Hours Daily 10 am – 6 pm Press contact Daniel Benyes T +43 (01) 534 83 511 | M +43 (0)699 12178720 [email protected] Sarah Wulbrandt T +43 (01) 534 83 512 | M +43 (0)699 10981743 [email protected] 2 American Photography 24 August - 28 November 2021 The exhibition American Photography presents an overview of the development of US American photography between the 1930s and the 2000s. With works by 33 artists on display, it introduces the essential currents that once revolutionized the canon of classic motifs and photographic practices. The effects of this have reached far beyond the country’s borders to the present day. The main focus of the works is on offering a visual survey of the United States by depicting its people and their living environments. A microcosm frequently viewed through the lens of everyday occurrences permits us to draw conclusions about the prevalent political circumstances and social conditions in the United States, capturing the country and its inhabitants in their idiosyncrasies and contradictions. In several instances, artists having immigrated from Europe successfully perceived hitherto unknown aspects through their eyes as outsiders, thus providing new impulses. -

Street Seen Teachers Guide

JAN 30–APR 25, 2010 THE PSYCHOLOGICAL GESTURE IN AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE CONTENTS 2 Using This Teachers Guide 3 A Walk through Street Seen 10 Vocabulary 11 Cross-Curricular Activities 15 Lesson Plan 18 Further Resources cover image credit Ted Croner, Untitled (Pedestrian on Snowy Street), 1947–48. Gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 in. Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. ©Ted Croner Estate prepared by Chelsea Kelly, School & Teacher Programs Manager, Milwaukee Art Museum STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 1 USING THIS TEACHERS GUIDE This guide, intended for teachers of grades 6–12, is meant to provide background information about and classroom implementation ideas inspired by Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959, on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum through April 25, 2010. In addition to an introductory walk-through of the exhibition, this guide includes useful vocabulary, discussion questions to use in the galleries and in the classroom, lesson ideas for cross-curricular activities, a complete lesson plan, and further resources. Learn more about the exhibition at mam.org/streetseen. Let us know what you think of this guide and how you use it. Email us at [email protected]. STREET SEEN: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 TEACHERS GUIDE 2 A WALK THROUGH STREET SEEN This introduction follows the organization of the exhibition; use it and the accompanying discussion questions as a guide when you walk through Street Seen with your students. Street Seen: The Psychological Gesture in American Photography, 1940–1959 showcases the work of six American artists whose work was directly influenced by World War II. -

How I Learned to See: an (Ongoing) Education in Pictures

For immediate release How I Learned to See: An (Ongoing) Education In Pictures Curated by Hanya Yanagihara Fraenkel Gallery 49 Geary Street, San Francisco June 30 – August 20, 2016 Fraenkel Gallery is pleased to present How I Learned to See: An (Ongoing) Education in Pictures, Curated by Hanya Yanagihara, from June 30 – August 20, 2016, at 49 Geary Street. The exhibition brings together a varied array of photographs that Yanagihara has chosen for their significance to her growth as an artist. The overarching theme is one of a writer looking deeply at other artists’ creative work—specifically, photographs—as a process of learning and discovery. Hanya Yanagihara is an American novelist whose most recent book, A Little Life, was a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award and shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker Prize and the 2016 Baileys Prize for Fiction. She has been a periodic visitor to Fraenkel Gallery for 17 years. Yanagihara remarked: The challenge for any artist, in any medium, is to find work that inspires her to re-see the things and people and places she thought she knew or understood. So much of my artistic development is directly linked to the images and photographers I encountered through years of visiting Fraenkel Gallery; the work here has, in ways both direct and not, influenced my own fiction. How I Learned to See is organized by six sections or “chapters” on the subjects of loneliness, love, aging, solitude, beauty, and discovery. Yanagihara has selected an idiosyncratic mix, with iconic and less familiar works by 12 artists: Robert Adams, Diane Arbus, Elisheva Biernoff, Harry Callahan, Lee Friedlander, Nan Goldin, Katy Grannan, Peter Hujar, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, Richard Misrach, Nicholas Nixon, Alec Soth, and Hiroshi Sugimoto. -

America Through Street Photography

From the Instructor Sarah wrote this piece for my section of the Genre and Audience WR X cluster. Students had undertaken semester-long research projects and, in the final assignment for the course, were asked to reimagine their academic arguments for a public audience. Deciding to write in the style of The New Republic, which is, in the publication’s own words, “tailored for smart, curi- ous, socially aware readers.” Sarah’s focus on street photography brings her research on classic American images to a non-expert audience with diverse professional and disciplinary perspectives, appealing to their interests in history and the arts while tapping into contemporary culture. — Gwen Kordonowy WR 150: The American Road 135 From the Writer When I enrolled in an experimental writing class entitled “The American Road,” I assumed that the semester would be filled with discussions about the physical American road, its attractions, and its place in American history. While the physical road was an important subject in the class, I learned that this “American Road” was expansive beyond its physical limi- tations, able to encompass topics as broad and abstract as social progress, popular television shows, and, in my case, photography. I ultimately chose to investigate the works of two American street photographers, Robert Frank and Lee Friedlander, whose approaches to photography reveal much about life in America and what it means to be an American. While both photographers frequently feature the road in their pictures, I chose to focus more on the people and culture found alongside it and how they represent America. -

Notable Photographers Updated 3/12/19

Arthur Fields Photography I Notable Photographers updated 3/12/19 Walker Evans Alec Soth Pieter Hugo Paul Graham Jason Lazarus John Divola Romuald Hazoume Julia Margaret Cameron Bas Jan Ader Diane Arbus Manuel Alvarez Bravo Miroslav Tichy Richard Prince Ansel Adams John Gossage Roger Ballen Lee Friedlander Naoya Hatakeyama Alejandra Laviada Roy deCarava William Greiner Torbjorn Rodland Sally Mann Bertrand Fleuret Roe Etheridge Mitch Epstein Tim Barber David Meisel JH Engstrom Kevin Bewersdorf Cindy Sherman Eikoh Hosoe Les Krims August Sander Richard Billingham Jan Banning Eve Arnold Zoe Strauss Berenice Abbot Eugene Atget James Welling Henri Cartier-Bresson Wolfgang Tillmans Bill Sullivan Weegee Carrie Mae Weems Geoff Winningham Man Ray Daido Moriyama Andre Kertesz Robert Mapplethorpe Dawoud Bey Dorothea Lange uergen Teller Jason Fulford Lorna Simpson Jorg Sasse Hee Jin Kang Doug Dubois Frank Stewart Anna Krachey Collier Schorr Jill Freedman William Christenberry David La Spina Eli Reed Robert Frank Yto Barrada Thomas Roma Thomas Struth Karl Blossfeldt Michael Schmelling Lee Miller Roger Fenton Brent Phelps Ralph Gibson Garry Winnogrand Jerry Uelsmann Luigi Ghirri Todd Hido Robert Doisneau Martin Parr Stephen Shore Jacques Henri Lartigue Simon Norfolk Lewis Baltz Edward Steichen Steven Meisel Candida Hofer Alexander Rodchenko Viviane Sassen Danny Lyon William Klein Dash Snow Stephen Gill Nathan Lyons Afred Stieglitz Brassaï Awol Erizku Robert Adams Taryn Simon Boris Mikhailov Lewis Baltz Susan Meiselas Harry Callahan Katy Grannan Demetrius -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

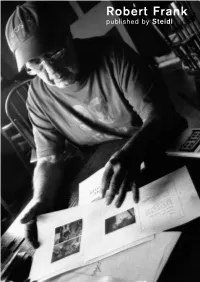

Robert Frank Published by Steidl

Robert Frank published by Steidl The Robert Frank Project “The Robert Frank Project” is an ambitious long term publishing programme which encompasses Robert Frank’s complete oeuvre – reprints of his classic books, reprints of some less well known small books, the publication of previously unseen projects, newly conceived bookworks, and his Complete Film Works in specially designed col- lector’s DVD sets. This ensures the legacy of this original and seminal artist and that Robert Frank’s work will be available and accessible for many years to come in a sche- me and to a standard that the artist himself has overseen. The publication of a new edition of “The Americans” on 15th May, 2008, the fiftieth anniversary of the first edition, is the fulcrum of The Robert Frank Project. It presages a major touring exhibition and accompanying catalogue from the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., “Looking In: Robert Frank’s The Americans”, which opens in January 2009. This brochure contains details of all the books and films which are currently available and those planned for the future. Gerhard Steidl Ute Eskildsen Laura Israel Publisher Editorial Adviser Film Works Adviser Delpire, 1958 Il Saggiatore, 1959 Grove Press, 1959 Delpire, 1993 Aperture, 1969 Christian, 1986 Scalo, 1993 Scalo, 2000 A Short Publishing History of “The Americans” by Monte Packham Robert Frank’s “The Americans” was first published in 1958 by Robert Delpire in Paris. It featured 83 of Frank’s photographs taken in America in 1955 and 1956, accompanied by writings in French about American political and social history selected by Alain Bosquet. -

Behind the Camera

BEHIND THE CAMERA BEHIND THE CAMERA CREATIVE TECHNIQUES OF 100 GREAT PHOTOGRAPHERS PRESTEL PAUL LOWE MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK Previous page People worshipping during the first prayers at Begova Dzamija mosque in Sarajevo, Bosnia, after its reopening following the civil war. Prestel Verlag, Munich · London · New York 2016 A member of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH Neumarkter Strasse 28 · 81673 Munich Prestel Publishing Ltd. 14-17 Wells Street London W1T 3PD Prestel Publishing 900 Broadway, Suite 603 New York, NY 10003 www.prestel.com © 2016 Quintessence Editions Ltd. This book was produced by Quintessence Editions Ltd. The Old Brewery 6 Blundell Street London N7 9BH Project Editor Sophie Blackman Editor Fiona Plowman Designer Josse Pickard Picture Researcher Jo Walton Proofreader Sarah Yates Indexer Ruth Ellis Production Manager Anna Pauletti Editorial Director Ruth Patrick Publisher Philip Cooper All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of the copyright holder. Library of Congress Control Number: 2016941558 ISBN: 978-3-7913-8279-1 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Color reproduction by Bright Arts, Hong Kong. Printed in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., LTD. Foreword 6 Introduction 8 Key to creative tips and techniques icons 18 Contents Places 42 Spaces 68 Things 90 Faces 108 Bodies 134 Ideas 158 Moments 180 Stories 206 Documents 228 Histories 252 Bibliography 276 Glossary 278 Index 282 Picture credits 288 by Simon Norfolk by Foreword Foreword I happened to be in Paris on the night of the terrorist attacks at We were either totally wasting our time (the terrorists were the Bataclan concert hall and the Stade de France in 2015. -

Robert Frank: the Americans Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ROBERT FRANK: THE AMERICANS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Robert Frank,Jack Kerouac | 180 pages | 09 Jul 2009 | Steidl Publishers | 9783865215840 | English | Gottingen, Germany Robert Frank: The Americans PDF Book Tri-X film! On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the book's original publication 15 May , a new edition was published by Steidl. As he has done for every edition of The Americans , Frank changed the cropping of many of the photographs, usually including more information, and two slightly different photographs were used. Much of the criticism Frank faced was as well related to his photojournalistic style, wherein the immediacy of the hand-held camera introduced technical imperfections into the resulting images. Becker has written about The Americans as social analysis:. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Where are we going? It could seem as if Frank threw his Leica into the world and let it catch what it could, which happened, without fail, to be something exciting—fascination, pain, hilarity, disgust, longing. The show presented the work of Diane Arbus , Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand , who at the time were relatively little known younger-generation beneficiaries of Mr. Retrieved 5 July By Philip Gefter. Silverstein died in , Mr. Retrieved She is now known as Mary Frank. Over the next 10 years, Mr. Safe in neutral Switzerland from the Nazi threat looming across Europe, Robert Frank studied and apprenticed with graphic designers and photographers in Zurich, Basel and Geneva. Rizzo has been lighting the stages of Broadway for almost forty years. In , The Americans was finally published in the United States by Grove Press , with the text removed from the French edition due to concerns that it was too un-American in tone. -

The Photograph Collector Information, Opinion, and Advice for Collectors, Curators, and Dealers N E W S L T R

THE PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTOR INFORMATION, OPINION, AND ADVICE FOR COLLECTORS, CURATORS, AND DEALERS N E W S L T R Volume XLI, Nos. 7 & 8 Summer 2020 AUCTION REPORTS AND PREVIEWS IN THE AGE OF COVID-19 by Stephen Perloff Edward Burtynsky: Colorado River Delta #2, Near San Felipe, Baja, Mexico, 2011 ($15,000–$25,000) sold well above estimate for $52,500 at Christie’s, New York City. SPRING AUCTION REPORT continued Peter Beard: But past who can recall or done undo (Paradise Lost), 1977 ($70,000–$100,000) found a buyer at $118,750 at Christie’s, New York City. Christie’s online Photographs sale ending June 3 totaled $2,422,125 with a 50% buy-in rate. There were a few good results, but overall this must have been a disappointment to both Chris- tie’s and its consignors. In these unprecedented times this is not a reflection of just Christie’s, but a sober reflection on the state of the photography market. Clearly safe bets like Irving Penn and Peter Beard were at the top of the heap, but at prices well below the highs of just a year or two ago. Still, it is heartening to see that Penn’s Small Trades series is getting the recognition that his other series have had. The top ten were: • Peter Beard: But past who can recall or done undo (Paradise Lost), 1977 ($70,000– $100,000) at $118,750 • Irving Penn: Rag and Bone Man, London, 1951 ($40,000–$60,000) at $106,250 Irving Penn: Rag and Bone Man, London, 1951 IN THIS ISSUE ($40,000–$60,000) collected a bid of $106,250 at Christie’s, New York City. -

Museum of Modern Art in New York Exhibits New Acquisitions in Photography

Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibits new acquisition... http://www.artdaily.org/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=6253... 11:09 am / 16 °C The First Art Newspaper on the Net Established in 1996 Austria Tuesday, May 14, 2013 Home Last Week Artists Galleries Museums Photographers Images Subscribe Comments Search Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibits new acquisitions in photography Lynn Hershman Leeson. Robertaʼs Construction Chart #2. 1976. Chromogenic color print, printed 2003, 22 15/16 x 29 5/8″ (58.3 x 75.3 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Modern Womenʼs Fund. © 2013 Lynn Hershman Leeson. NEW YORK, NY.- The Museum of Modern Art presents XL: 19 New Acquisitions in Photography, featuring a selection of major works—often multipart and serial images—by 19 contemporary artists, from May 10, 2013, to January 6, 2014. The exhibition features works, made between 1960 and the present, which have been acquired by the Department of Photography within the past five years and are on view at MoMA for the first time. The exhibition is organized by Roxana Marcoci, Curator; Sarah Meister, Curator; and Eva Respini, Associate Curator; with Katerina Stathopoulou, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Photography, The Museum of Modern Art. Filling five consecutive rooms in the third-floor Edward Steichen Photography Galleries, this installation includes a diverse set of works—from performative photographs to collage and appropriation to political and personal images made in the documentary tradition—that underscore the vitality of photographic experimentation today. The cross-generational group of 19 international artists consists of Yto Barrada, Phil Collins, Liz Deschenes, Stan Douglas, VALIE EXPORT, Robert Frank, Paul Graham, Leslie Hewitt, Birgit Jürgenssen, Jürgen Klauke, Běla Kolářová, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Dóra Maurer, Oscar Muñoz, Mariah Robertson, Allan Sekula, Stephen Shore, Taryn Simon, and Hank Willis Thomas.