From Wright Field, Ohio, to Hokkaido, Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

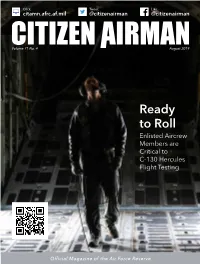

Ready to Roll Enlisted Aircrew Members Are Critical to C-130 Hercules Flight Testing

Click. Tweet. Like. citamn.afrc.af.mil @citizenairman @citizenairman Volume 71 No. 4 August 2019 Ready to Roll Enlisted Aircrew Members are Critical to C-130 Hercules Flight Testing Official Magazine of the Air Force Reserve From the Top @ AFRCCommander Chief’s View @ AFRC.CCC NEW LEADERS POISED TO ENHANCING TRUST IS DO GREAT THINGS FOR THE FIRST STEP THE COMMAND TO REFORMING THE The success of any organization and deploying ORGANIZATION depends on its leaders. The Air Force in support of Reserve is comprised of numerous units, U.S. Central In my last commentary, I rolled out three individual lines of and each has its own set of leaders. Some Command. effort – comprehensive readiness, deliberate talent management Lt. Gen. Richard Scobee passes the guidon to Col. Kelli Smiley, the new Lt. Gen. Richard Scobee and Chief Master Sgt. Timothy White meet with manage a section, others helm a num- Healy’s robust Air Reserve Personnel Center commander. Smiley is one of several new and enhancing organizational trust – to align with our strategic Reservists from the 624th Regional Support Group, Hickam Air Force bered Air Force, but all are leaders. We mobility back- senior leaders throughout the command. (Staff Sgt. Katrina M. Brisbin) priorities. Today, I want to focus on LOE3, enhancing organiza- Base, Hawaii. rely on each and every one to conduct ground and his tional trust. our day-to-day operations and provide time at the com- the challenges our Reservists face and During my most recent trip to Indo-Pacific Command, a opportunity to enhance trust in the organization, which directly outstanding support to our Airmen and batant commands make him well suited improve their quality of life. -

Heritage, Heroes, Horizons 50 Years of A/TA Tradition and Transformation

AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 26 • Number 4 • Fall 2018 Heritage, Heroes, Horizons 50 Years of A/TA Tradition and Transformation Pages 14 2018 A/TA Awards Pages 25-58 A Salute to Our Industry Partners Pages 60-69 Table of Contents 2018 A/TA Board of Offi cers & Convention Staff ..................................................................... 2 A/TA UpFront Chairman’s Comments. ............................................................................................................. 4 President’s Message .................................................................................................................... 5 Secretary’s Notes ........................................................................................................................ 6 AIRLIFT/TANKER QUARTERLY Volume 26 • Number 4 • Fall 2018 The Inexorable March of Time, an article by Col. Dennis “Bud” Traynor, USAF ret ...................7 ISSN 2578-4064 Airlift/Tanker Quarterly is published four times a year by the Features Airlift/Tanker Association, 7983 Rhodes Farm Way, Chattanooga, A Welcome Message from Air Mobility Command Commader General Maryanne Miller ...... 8 Tennessee 37421. Postage paid at St. Louis, Missouri. Subscription rate: $40.00 per year. Change of address A Welcome Message from Air Mobility Command Chief Master Sergeant Larry C. Williams, Jr... 10 requires four weeks notice. The Airlift/Tanker Association is a non-profi t professional Cover Story organization dedicated to providing a forum for people Heritage, Heores, Horizons interested -

United States Air Force Headquarters, 3Rd Wing Elmendorf AFB, Alaska

11 United States Air Force Headquarters, 3rd Wing Elmendorf AFB, Alaska Debris Removal Actions at LF04 Elmendorf AFB, Alaska FINAL REPORT April 10, 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ............................ ................ .............................. 1 1.1 Project Objectives ............................................ 1 1.2 Scope of Work ................................................................... 1 1.3 Background Information ............................................ 1 1.3.1 Historical Investigations and Remedial Actions ........................................ 3 2 Project E xecution .................................................................................................................... 3 2.1 Mobilization ..................................................................................................... 3 2.2 E quipm ent ....................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 T ransportation ................................................................................................................. 4 2.4 Ordnance Inspection ...... ........................................ 4 2.5 Debris Removal ................................................................................................... 4 2.6 Debris Transportation and Disposal ...................................... 5 2.7 Site Security .................................................................................................................... 5 2.8 Security Procedures -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

Major Commands and Air National Guard

2019 USAF ALMANAC MAJOR COMMANDS AND AIR NATIONAL GUARD Pilots from the 388th Fighter Wing’s, 4th Fighter Squadron prepare to lead Red Flag 19-1, the Air Force’s premier combat exercise, at Nellis AFB, Nev. Photo: R. Nial Bradshaw/USAF R.Photo: Nial The Air Force has 10 major commands and two Air Reserve Components. (Air Force Reserve Command is both a majcom and an ARC.) ACRONYMS AA active associate: CFACC combined force air evasion, resistance, and NOSS network operations security ANG/AFRC owned aircraft component commander escape specialists) squadron AATTC Advanced Airlift Tactics CRF centralized repair facility GEODSS Ground-based Electro- PARCS Perimeter Acquisition Training Center CRG contingency response group Optical Deep Space Radar Attack AEHF Advanced Extremely High CRTC Combat Readiness Training Surveillance system Characterization System Frequency Center GPS Global Positioning System RAOC regional Air Operations Center AFS Air Force Station CSO combat systems officer GSSAP Geosynchronous Space ROTC Reserve Officer Training Corps ALCF airlift control flight CW combat weather Situational Awareness SBIRS Space Based Infrared System AOC/G/S air and space operations DCGS Distributed Common Program SCMS supply chain management center/group/squadron Ground Station ISR intelligence, surveillance, squadron ARB Air Reserve Base DMSP Defense Meteorological and reconnaissance SBSS Space Based Surveillance ATCS air traffic control squadron Satellite Program JB Joint Base System BM battle management DSCS Defense Satellite JBSA Joint Base -

Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Is Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Washingto

Gen. Mark A. Welsh III Chief of Staff of the Air Force Gen. Mark A. Welsh III is Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force, Washington, D.C. As Chief, he serves as the senior uniformed Air Force officer responsible for the organization, training and equipping of 690,000 active-duty, Guard, Reserve and civilian forces serving in the United States and overseas. As a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the general and other service chiefs function as military advisers to the Secretary of Defense, National Security Council and the President. General Welsh was born in San Antonio, Texas. He entered the Air Force in June 1976 as a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy. He has been assigned to numerous operational, command and staff positions. Prior to his current position, he was Commander, U.S. Air Forces in Europe. EDUCATION 1976 Bachelor of Science degree, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs, Colo. 1984 Squadron Officer School, by correspondence 1986 Air Command and Staff College, by correspondence 1987 Master of Science degree in computer resource management, Webster University 1988 Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kan. 1990 Air War College, by correspondence 1993 National War College, Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C. 1995 Fellow, Seminar XXI, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge 1998 Fellow, National Security Studies Program, Syracuse University and John Hopkins University, Syracuse, N.Y. 1999 Fellow, Ukrainian Security Studies, John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. 2002 The General Manager Program, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. -

Aircraft Engines and Strategic Bombing in the First World War

Aircraft Engines and Strategic Bombing in the First World War Todd Martin Published: 27 January 2016 Contents Historiography, Acknowledgments and Introduction . .3 Table I: Comparative Aircraft Engines . .5 Table II: Aircraft Engine Production, 1914-1918 . .5 Map: British Independent Force Squadron No. 55 DH-4 Day Bombing Raids, Germany, 1918 . .6 Abbreviations . .7 Part I: Aircraft Engines 1. Austria and Germany . .8 2. France . .17 3. United States . .23 4. Britain . .29 Part II: Strategic Bombing 5. The Channel . .37 6. The Rhine . .46 7. Amanty . .53 Conclusion . .69 Bibliography . .70 Title Page: NARA, RG 120, M990/10, B VII 124, Statistical Analysis of Aerial Bombardments, Report No. 110, Statistics Branch - General Staff, War Department, Nov. 7, 1918. 2 Historiography, Acknowledgements and Introduction Historiography and Acknowledgments arithmetic however which makes the following a revi- The following avoids repeating much of the well sion of the thesis of Irving B. Holley, Jr.’s Ideas and known stories of the Liberty aircraft engine and the Weapons (1953) that the American military aviation controversies surrounding American aviation in the effort in the First World War failed due to a lack of First World War. It also avoids offering a definition of airpower doctrine, a revision the need for which is strategic bombing, save to suggest that economic war- pointed to in the second volume of Mauer Mauer’s fare may be properly considered to be an element of edition of The U.S. Air Service in World War I (1978.) that definition. The following adheres to the long The continuing efforts to understand the world established understanding that many of the aircraft wars as a single historical event and to study them engines successfully used during that war were “from the middle” perspective of technology and derived from an engine designed before the war by engineering1 are appropriate and admirable and thus Ferdinand Porsche. -

1945-12-11 GO-116 728 ROB Central Europe Campaign Award

GO 116 SWAR DEPARTMENT No. 116. WASHINGTON 25, D. C.,11 December- 1945 UNITS ENTITLED TO BATTLE CREDITS' CENTRAL EUROPE.-I. Announcement is made of: units awarded battle par- ticipation credit under the provisions of paragraph 21b(2), AR 260-10, 25 October 1944, in the.Central Europe campaign. a. Combat zone.-The.areas occupied by troops assigned to the European Theater of" Operations, United States Army, which lie. beyond a line 10 miles west of the Rhine River between Switzerland and the Waal River until 28 March '1945 (inclusive), and thereafter beyond ..the east bank of the Rhine.. b. Time imitation.--22TMarch:,to11-May 1945. 2. When'entering individual credit on officers' !qualiflcation cards. (WD AGO Forms 66-1 and 66-2),or In-the service record of enlisted personnel. :(WD AGO 9 :Form 24),.: this g!neial Orders may be ited as: authority forsuch. entries for personnel who were present for duty ".asa member of orattached' to a unit listed&at, some time-during the'limiting dates of the Central Europe campaign. CENTRAL EUROPE ....irst Airborne Army, Headquarters aMd 1st Photographic Technical Unit. Headquarters Company. 1st Prisoner of War Interrogation Team. First Airborne Army, Military Po1ie,e 1st Quartermaster Battalion, Headquar- Platoon. ters and Headquarters Detachment. 1st Air Division, 'Headquarters an 1 1st Replacementand Training Squad- Headquarters Squadron. ron. 1st Air Service Squadron. 1st Signal Battalion. 1st Armored Group, Headquarters and1 1st Signal Center Team. Headquarters 3attery. 1st Signal Radar Maintenance Unit. 19t Auxiliary Surgical Group, Genera]1 1st Special Service Company. Surgical Team 10. 1st Tank DestroyerBrigade, Headquar- 1st Combat Bombardment Wing, Head- ters and Headquarters Battery.: quarters and Headquarters Squadron. -

Wreaths to Remember Page 8

=VS5V Thursday, December 21, 2017 WHNL 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH >YLH[OZ[VYLTLTILY &UHZFKLHIVNHHS¶HPÁ\LQJ 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH 5DUHWDQNHU·VQHZKRPH :HHNLQSKRWRVSDJH ,PDJHVIURPWKHZHHN 1HZV)HDWXUHVSDJH 2SHUDWLRQ&KULVWPDV'URS 7OV[VI`(PYTHUZ[*SHZZ(ZOSL`7LYK\L <: (PY -VYJL :LUPVY (PYTHU 9HJOLS *HJOV HU HPYJYHM[ LSLJ[YPJHS HUK LU]PYVUTLU[HS Z`Z[LTZ HWWYLU[PJL ^P[O [OL [O (PYJYHM[4HPU[LUHUJL:X\HKYVUWSHJLZH^YLH[OVUHNYH]LZP[LK\YPUN[OL>YLH[OZ(JYVZZ(TLYPJH>YLH[O3H`PUNHUK &RPPXQLW\SDJH 9LTLTIYHUJL*LYLTVU`H[[OL-SVYPKH5H[PVUHS*LTL[LY`PU)\ZOULSS-SH+LJ>YLH[OZ(JYVZZ(TLYPJHPZHUVU (YHQWV&KDSHOPRUH WYVMP[VYNHUPaH[PVUKLKPJH[LK[VOVUVYPUNHUK[OHURPUN]L[LYHUZMVY[OLPYZLY]PJLHUKZHJYPMPJL>OH[Z[HY[LKV\[PU(YSPUN[VU 5H[PVUHS*LTL[LY`>HZOPUN[VU+*[OLJLYLTVU`UV^[HRLZWSHJLPUV]LYSVJH[PVUZHJYVZZ[OL^VYSK COMMENTARY (4*JVTTHUKJOPLMYLMSLJ[ZVU`LHYJHYLLY I`*OPLM4HZ[LY:N[:OLSPUH-YL` "JS.PCJMJUZ$PNNBOEDPNNBOEDIJFG SCOTT AIR FORCE BASE, Ill. — Happy holidays! It is a great honor to serve as your command chief. At the end of each year, I take time to re- flect on all Air Mobility Command accomplishments over the year – and this command never ceases to amaze me! This year is no different. AMC enjoyed an extremely successful year be- cause of our Mobility Airmen. With that, I offer you and your families my sincerest thanks. Because of your unwavering commitment to the mission and the support and sacrifices your families make, we are able to generate Rapid Global Mobility for America. As this year comes to a close, I’m especially reflective because this may be my last holiday season on active duty. -

Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010

Description of document: US Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Impersonal Names Index Listing for the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository, 2010 Requested date: 07-August-2010 Released date: 15-August-2010 Posted date: 23-August-2010 Title of document Impersonal Names Index Listing Source of document: Commander U.S. Army Intelligence & Security Command Freedom of Information/Privacy Office ATTN: IAMG-C-FOI 4552 Pike Road Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755-5995 Fax: (301) 677-2956 Note: The IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents INSCOM investigative files that are not titled with the name of a person. Each item in the IMPERSONAL NAMES index represents a file in the INSCOM Investigative Records Repository. You can ask for a copy of the file by contacting INSCOM. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. -

Fifty Years on Nato's Southern Flank

FIFTY YEARS ON NATO’S SOUTHERN FLANK A HISTORY OF SIXTEENTH AIR FORCE 1954 – 2004 By WILLIAM M. BUTLER Sixteenth Air Force Historian Office of History Headquarters, Sixteenth Air Force United States Air Forces in Europe Aviano Air Base, Italy 1 May 2004 ii FOREWORD The past fifty years have seen tremendous changes in the world and in our Air Force. Since its inception as the Joint U.S Military Group, Air Administration (Spain) responsible for the establishment of a forward presence for strategic and tactical forces, Sixteenth Air Force has stood guard on the southern flank of our NATO partners ensuring final success in the Cold War and fostering the ability to deploy expeditionary forces to crises around our theater. This history then is dedicated to all of the men and women who met the challenges of the past 50 years and continue to meet each new challenge with energy, courage, and devoted service to the nation. GLEN W. MOORHEAD III Lieutenant General, USAF Commander iii PREFACE A similar commemorative history of Sixteenth Air Force was last published in 1989 with the title On NATO’s Southern Flank by previous Sixteenth Air Force Historian, Dr. Robert L. Swetzer. This 50th Anniversary edition contains much of the same structure of the earlier history, but the narrative has been edited, revised, and expanded to encompass events from the end of the Cold War to the emergence of today’s Global War on Terrorism. However, certain sections in the earlier edition dealing with each of the countries in the theater and minor bases have been omitted. -

Spring 2011.Indd

Airfield Bases of the 2nd Air Division Official Publication of the: Volume 50 Number 1 Spring 2011 At the Imperial War Museum, Duxford: Consolidated B-24M Liberator “DUGAN” Submitted by our British friend John Threlfall, who obtained this info from the staff of the Imperial War Museum, Duxford. John says, “The American collection there is, I think, the biggest outside the USA. I am content now as I have actually seen and touched a B-24.” f similar size to the B-17 Flying Fortress, the Liberator was a later and more advanced design, the prototype flying in 1939. The B-24 O was built in larger numbers than any other American aircraft of the Second World War. Five production plants delivered 19,256 Lib- erators. The Ford Motor Company alone, using automobile industry mass production techniques, built 6,792 at its Willow Run plant. B-24s flew one of the most famous American bombing raids of the war, Operation Tidal Wave, the raid on Ploesti. On 1 August 1943 they made a low-level attack on the Romanian oil fields, which supplied one-third of German high-octane fuel. Only the Liberator had the range to reach these targets from airfields in North Africa. Of the 179 aircraft dispatched, 56 were lost, and of 1,726 airmen involved, 500 lost their lives. Five airmen received the Medal of Honor, a record for one operation. With its long range, the Liberator also played a key role with the U.S. Navy and RAF Coastal Command against German U-boats in the Battle of the Atlantic.