Spejean History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tennessee Archaeology 2(2) Fall 2006

TTEENNNNEESSSSEEEE AARRCCHHAAEEOOLLOOGGYY Volume 2 Fall 2006 Number 2 EDITORIAL COORDINATORS Michael C. Moore TTEENNNNEESSSSEEEE AARRCCHHAAEEOOLLOOGGYY Tennessee Division of Archaeology Kevin E. Smith Middle Tennessee State University VOLUME 2 Fall 2006 NUMBER 2 EDITORIAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE David Anderson 62 EDITORS CORNER University of T ennessee ARTICLES Patrick Cummins Alliance for Native American Indian Rights 63 The Archaeology of Linville Cave (40SL24), Boyce Driskell Sullivan County, Tennessee University of T ennessee JAY D. FRANKLIN AND S.D. DEAN Jay Franklin 83 Archaeological Investigations on Ropers East Tennessee State University Knob: A Fortified Civil War Site in Williamson County, Tennessee Patrick Garrow BENJAMIN C. NANCE Dandridge, Tennessee Zada Law 107 Deep Testing Methods in Alluvial Ashland City, Tennessee Environments: Coring vs. Trenching on the Nolichucky River Larry McKee SARAH C. SHERWOOD AND JAMES J. KOCIS TRC, Inc. Tanya Peres RESEARCH REPORTS Middle Tennessee State University 120 A Preliminary Analysis of Clovis through Sarah Sherwood Early Archaic Components at the Widemeier University of Tennessee Site (40DV9), Davidson County, Tennessee Samuel D. Smith JOHN BROSTER, MARK NORTON, BOBBY HULAN, Tennessee Division of Archaeology AND ELLIS DURHAM Guy Weaver Weaver and Associates LLC Tennessee Archaeology is published semi-annually in electronic print format by the Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology. Correspondence about manuscripts for the journal should be addressed to Michael C. Moore, Tennessee Division of Archaeology, Cole Building #3, 1216 Foster Avenue, Nashville TN 37210. The Tennessee Council for Professional Archaeology disclaims responsibility for statements, whether fact or of opinion, made by contributors. On the Cover: Ceramics from Linville Cave, Courtesy, Jay Franklin and S.D. -

Illinois Archaeological Collections at the Logan Museum of Anthropology

Illinois Archaeological Collections at the Logan Museum of Anthropology William Green The Logan Museum of Anthropology houses thousands of objects from Illinois archaeologi- cal sites. While many objects have useful associated documentation, some collections lack contextual data. Provenance investigations can restore provenience information, mak- ing neglected or forgotten collections useful for current and future research. Provenance research also provides insights about the history of archaeology and the construction of archaeological knowledge. Recent study of Middle Woodland collections from the Baehr and Montezuma mound groups in the Illinois River valley exemplifies the value of analyzing collection histories. Museum collections are significant archaeological resources. In addition to their educational value in exhibitions and importance in addressing archaeological research questions, collections also serve as primary-source material regarding the history of archaeology. If we pay close attention to collection objects and associated documenta- tion, we can learn how past practices of collecting and circulating objects have helped construct our current understandings of the cultures the objects represent. In this paper, I review Illinois archaeological collections housed at the Logan Mu- seum of Anthropology. The principal focus is on Middle Woodland material from the Illinois River valley. I examine the provenance—the acquisition and curation histories— of these collections and identify some topics the collections might address. -

Looking Beyond the Obvious: Identifying Patterns in Coles Creek Mortuary Data

Looking Beyond the Obvious: Identifying Patterns in Coles Creek Mortuary Data Megan C. Kassabaum University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill [Paper presented at the Southeastern Archaeological Conference, Charlotte, N.C., 2008] Two characteristics of prehistoric societies in the southeastern United States are commonly used to support arguments for the presence of chiefly political and social organization. One of these characteristics is the large-scale construction of earthworks (particularly large platform mound and plaza complexes); the other is the employment of elaborate mortuary ceremonialism and sumptuous burial goods. Some claim that the earliest indications of chiefdoms can be recognized in the indigenous Coles Creek tradition of southwestern Mississippi and east-central Louisiana. Around A.D. 700, people in this region began building large-scale earthworks similar to those of later, decidedly hierarchical Mississippian polities. However, previous investigators of mortuary remains from these Coles Creek sites report a paucity of burial goods and absence of ornate individual burials (Ford 1951; Giardino 1977; Neuman 1984). Due to the distinct presence of one traditional marker for hierarchical social organization and the reported lack of another, the issue of Coles Creek social differentiation remains a paradox for Southeastern archaeologists. While a relatively small number of Coles Creek sites have been satisfactorily excavated, further analysis of data from these previous archaeological investigations may still reveal significant -

William Henry Holmes Papers, 1870-1931

William Henry Holmes Papers, 1870-1931 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: CORRESPONDENCE. ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY. 1882-1931................................................................................................................. 4 Series 2: CORRESPONDENCE. ARRANGED NUMERICALLY BY WILLIAM HENRY HOLMES. 1870-1931................................................................................. 6 Series 3: CORRESPONDENCE. ARRANGED BY SUBJECT................................. 7 Series 4: MEMORABILIA......................................................................................... 8 Series 5: FIELD NOTES, SKETCHES, AND PHOTOGRAPHS.............................. -

More Than a Fossil-Hunter: the Life and Pursuits of Charles W. Beehler

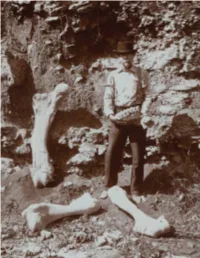

4 | The Confluence | Spring/Summer 2013 The Life and Pursuits of Charles W. Beehler BY R. BRUCE MCMILLAN In the decade preceding the 1904 Louisiana Purchase an upholsterer and mattress maker by trade, catering to the Exposition, a St. Louis native of German descent became needs of steamboats and hotels from his business near the well known for his discovery of mastodon remains and riverfront on north Second Street.3 The Beehler residence other fossils he excavated from the legendary Kimmswick was situated three blocks away on Fifth Street. “bone-bed” in Jefferson County, Missouri. C. W. Beehler When C. W. Beehler was seven years old a massive spent the dawn of the twentieth century amassing a large fire (June 19, 1851) destroyed the block of buildings on collection of fossils that he housed in a small frame Second Street owned by his father, a loss estimated at building at the site along Rock Creek, which he referred $45,000. The buildings housed Francis Beehler’s mattress to as a museum. Beehler promoted his enterprise in St. factory and a furniture store owned by W. H. Harlow. Louis, and as the World’s Fair approached he arranged Only a fraction of the loss―$5,000―was covered by for day trips by train from St. Louis for people to view insurance.4 Ironically, soon afterward Francis Beehler his excavations and large collection of fossils. As word became a board member of the St. Louis Mutual Life and of his endeavor reached learned individuals around the Health Insurance Company.5 After the fire Francis Beehler country, including scientists in the hallowed halls of moved his business a block south to 78 North Second the American Museum of Natural History in New York Street where he reopened his mattress and upholstery and the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, Beehler company. -

The Clark Family History” by Linda Benson Cox, 2003; Edited, 2006 “Take Everything with a Grain of Salt”

“The Clark Family History” By Linda Benson Cox, 2003; Edited, 2006 “Take everything with a grain of salt” Old abandoned farmhouse, 2004 View of the Tennessee River Valley looking toward Clifton, 2004 "Let us go to Tennessee. We come, you and I, for the music and the mountains, the rivers and the cotton fields, the corporate towers and the country stores. We come for the greenest greens and the haziest blues and the muddiest browns on earth. We come for the hunters and storytellers, for the builders and worshippers. We come for dusty roads and turreted cities, for the smells of sweet potato pie and sweat of horses and men. We come for our quirkiness and our cleverness. We come to celebrate our common 1 bonds and our family differences." REVEREND WILLIAM C. CLARK While Tennessee was still a territory, trappers and scouts were searching for prospective home sites in West Tennessee including the area where Sardis now stands. Soon families followed these scouts over the mountains of East Tennessee into Middle Tennessee. Some remained in Middle Tennessee, but others came on into West Tennessee in a short time. Thus, some settled in Sardis and the surrounding area...the roads were little more than blazed paths…as did other early settlers, the first settlers of Sardis settled near a spring…as early as 1825, people from miles around came to this “Big Meeting” place just as others were gathering at other such places during that time of great religious fervor. It was Methodist in belief, but all denominations were made welcome…as a result of the camp meetings people began to come here and establish homes. -

Summary of the Archeology of Saginaw Valley, Michigan

SUMMARY OF THE ARCHEOLOGY OF SAGINAW VALLEY, MICHIGAN BY HARLAN I. SMITH INTRODUCTION Saginaw valley, including the entire area draining into Saginaw bay, occupies the east central region of the southern peninsula of Michigan. It is a well-watered, level, timber country, formerly covered by dense forests of pine, oak, elm, ash, maple, hickory, and other trees. The low-lands are occupied by swamps which in places are largely grown up with wild rice (Zizania aquatica), a staple produced by nature in such abundance that it was of great importance to the primitive people of the region when they were first met by the whites.’ The streams which most concerned the prehistoric inhabitants of the valley were Saginaw river and its main tributaries including the Shiawassee, Flint, Bad, Cass, Tittabawassee, and their branches ; while the Pigeon, Sebewaing, Kawkawlin, and Rifle were also important. Bordering the lower courses of the river, are numerous bayous ; interspersed over the intervening country are low sand ridges. At the headwaters the streams flow more swiftly and undercut their banks because their beds have greater fall, consequently large bayous and swamps are less frequent. Rocks of the subcarboiiiferous series, bearing chert nodules, outcrop in a nearly circular line cut by the headwaters of the Cass, Shiawassee, and Tittabawassee, and intersecting Saginaw bay near Point Lookout and Hay Port. This chert was extensively quarried __ Stickney (Gardncr I’.), “ Indian Use of Wild Rice.” Anierican AntAropolop3, Washington, vol. IX, No. 4, April, 1896, pp, 115-121, 111. 2. Copies : University at Ann .4rbor. 286 and chipped into implements by the prehistoric occupants of the valley. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1921, Volume 16, Issue No. 1

MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE PUBLISHED UNDEK THE AUTHOBITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XVI BALTIMORE 1921 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XVI PAGE COLONEL GEEAED FOWKE. Gerard Fowke, 1 SOME EABLY COLONIAL MABYLANDEBS. McEenry Howard, - 19, 179 EXTBACTS FROM THE CABBOLL PAPEBS, 29 EXTRACTS FEOM THE DULANY PAPEBS, 43 THE CALVEBT FAMILY. John Bailey Calvert Nicklin, 50, 189, 313, 389 CASE OF THE "GOOD INTENT," 60 PEOCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, 63, 394 LIST OF MEMBEBS OF THE SOCIETY, 80 BALTIMORE COUNTY " GABEISON " AND THE OLD GABEISON ROADS. William B. Marye, 105, 207 COBEESPONDENCE OF JAMES ALFEED PEAECE. Edited by Bernard C. Steiner, 150 EXTBACTS FEOM THE ANNUAL EEPOBT OF THE GALLERY COMMITTEE OF THE MAEYLAND HlSTOBICAL SOCIETY, - - - - 204 THE LIFE OF THOMAS JOHNSON. Edward 8. Delaplaine, - 260, 340 NOTES FEOM THE EABLY EEOOEDS OF MAEYLAND. Jane Baldwin Cotton, 279, 369 CATONSVILLE BIOGEAPHIES. George C. Keidel, - - - - 299 JAMES ALFEED PEAECE, Bernard C. Steiner, . 319 UNPUBLISHED PBOVINCIAL EEOOEDS, 354 THE CALVEBT FAMILY MEMOEABILIA, 386 NOTES, BOOKS RECEIVED, ETC., 403 MARYLAND HISTORICAL MAGAZINE VOL. XVI. MARCH, 1921. No. 1 COLONEL aERARD FOWKE OF VIKGINIA AND MARYLAND., FBOM 1651. GEEAED FOWKE, St. Louis, Mo. Eamily tradition, usually unreliable, asserts that the Fowkes are descended from Fulk, Count of Anjou, France, in the ninth century. This belief is probably based on similarity of name, and the occurrence of the fleur-de-lis on the coat of arms. It is also believed that the first of tbe name came to England with Ricbard Cceur de Lion. But the name appears on the Battle Abbey roll, so tbey were bere as early as William the Con- queror. -

Toward a History of Plains Archeology

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for Winter 1981 Toward A History Of Plains Archeology Waldo R. Wedel Smithsonian Institution Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Wedel, Waldo R., "Toward A History Of Plains Archeology" (1981). Great Plains Quarterly. 1919. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1919 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TOWARD A HISTORY OF PLAINS ARCHEOLOGY WALDO R. WEDEL First viewed by white men in 1541, the North the main areas of white settlement, the native American Great Plains remained little known peoples of the plains retained their tribal iden and largely misunderstood for nearly three tities and often colorfullifeways long after the centuries. The newcomers from Europe were entry of Euroamericans. Since early in the impressed by the seemingly endless grasslands, nineteenth century, following acquisition of the the countless wild cattle, and the picturesque Louisiana territory by the United States, perti tent-dwelling native people who followed the nent observations by such persons as Meri herds, subsisting on the bison and dragging their wether Lewis, William Clark, Zebulon M. Pike, possessions about on dogs. Neither these Stephen H. Long, George Catlin, Prince Maxi Indians nor the grasslands nor their fauna had milian of Wied-Neuwied, and a host of others any counterparts in the previous experience of less well known, have left a wealth of ethno the Spaniards. -

ARK-LA-TEX GENEALOGICAL ASSOCIATION, INC. P.O

.- Since April VOLUME VIII NUMBER 1 JANUARY 1974 PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY ARK-LA-TEX GENEALOGICAL ASSOCIATION, INC. P.o. BOX 71 SHREVEPORT. LOUISIANA 71161 ARK-LA - TEX GENEALOGICAL ASSOCIATION, INC. P. O. Box 71 Shreveport, Louisiana 71161 Organized 1955 Publlshing THE GENIE Slnce 1967 OFFICERS FOR 1974 President: Dr. Thomas Vinton Holmes, Jr. 1st Vice Pres: Mr. M. L. "Pete" Nance, Program Chairman & Pubhcity Committee 2nd Vice Pres: Mrs. Johnnie D. Womble Librarian: Mrs. Margery Wright Recording Sec: Mrs. James T. Evans Corres. Sec.: Mrs. Barbara Smith Treasurer: Mrs. Mary Jewell Moore Chairman of Committee for publication of The Genie: Mr. M. L. Nance. TRUSTEES FOR 1974 Mrs. Irwin M. Reynolds Mr. Ennis M. Tlpton, Jr. Past Pres. Mr. Jack Perryman Mrs. Wm. O. Weaver REGULAR MEETINGS: Second Saturday of each month, 2:00 to 4:00 p. m. EXTENSION LIBRARY, 3240 Creswell st., Shreveport, La . BOARD MEETINGS: Second Saturday of each month at 1:00 p. m. at the EXTENSION LIBRARY, 3240 Creswell st. Shreveport, La . MEMBERSHIP DUES: Per calendar year, Jan 1, to Dec 31. $5.00 per year, 1974 All members receive four lssues of THE GENIE per year. Queries are published free. THE GENIE: Published quarterly, January, April, July, October each year. All Genealogical materials of this Association are deposited In the Genealogy Room of SHREVE MEMORIAL LIBRARY, 400 Edwards Street, Shreveport, La. for the use of all genealoglst and historians who use its facillties. The Ark-La-Tex Genealogical Association, Inc. is a non-proflt, non-sectarian, non-political, educational organization, dedicated solely to the cause of Genealogical work, which includes the following purposes: To collect, preserve and make available genealogical materials, documents and records. -

Download Download

PROCEEDINGS OF THE Fortieth Annual Meeting Indiana Academy of Science VOLUME 34 1924 J. J. Davis, Editor Held at Purdue University Lafayette, Indiana December 4-6, 1924 INDIANAPOLIS: \VM. B. BURFORD, CONTRACTOR FOR STATE PRINTING AND BINDING 1925 — —— Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Officers and Committees for 1924 7 Officers and Committees for 1925 8 Past Officers of the Academy 10 Minutes of the Spring Meeting, 1924 11 Winter Meeting Program 15 Minutes of Executive Committee 21 Minutes of General Session 26 Memorials Stephen Francis Balcom : R. W. McBride 31 Robert Greene Gillum : L. J. Rettger 33 William Allen McBeth : L. J. Rettger 35 John C. Shirk: Amos W. Butler 38 Papers—General President's Address—Flora of Indiana: On the Distribution of the Ferns, Fern Allies and Flowering Plants: Chas. C. Deam 39 The Evolution of Botany: John Merle Coulter, University of Chicago 55 The Evolution of a Botanist aid of a Department of Botany: Will- iam Trelease, University of Illinois 59 The Conservation Commission and its Work: Stanley Coulter, Purdue University 63 City "Smogs" in Periods of General Fair Weather: J. H. Armington, U. S. Weather Bureau, Indianapolis 67 The Types of Errors Made in the Purdue English Test by High School Boys: Geraldine Frances Smith, Hammond 71 Papers on Geology, Geography, and Archeology— The Sub-Trenton Formations of Indiana: W. N. Logan, Indiana University 75 The Genesis of the Ohio River: Gerard Fowke, Madison, Indiana. ... 81 The Upper Chester of Indiana: Clyde A. Malott, Indiana University 103 Notes on Areal Geology of Jasper County, Indiana: T. -

Brief History of the Water Utilities in Peru, Indiana

HISTORY OF PERU, INDIANA WATER UTILITY The history of the water utilities in Peru, Indiana began in the 1870’s. Information on the beginning was published in a volume called History of Miami County Indiana, A Narrative Account of Its Historical Progress, Its People and Its Principal Interests, the volume was edited by Mr. Arthur L. Bodurhta. This volume was published by The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago and New York, 1914. An excerpt from the book is as follows: The proposition to establish a municipal water works system for the city of Peru first came before the council in 1871. At that time public sentiment was against the undertaking and no action was taken. On March 7, 1873, Governor Hendricks approved an act authoring cities to issue bonds for the purpose of building water works and the question was agitated for a time in Peru, but again no definite action was taken on the matter. In 1875, Shirk, Dukes & Company came forward with a proposal to build and equip a water works system adequate to the demands of the city under a franchise, but council declined to grant the franchise and once more the subject was dropped without any results having been obtained. In July, 1877, a special election was held to ascertain the sentiment of the voters with regard to the construction of water works, those in favor to vote a ballot declaring “For Water Works” and those opposed a ballot “Against Water Works” Upon canvassing the returns it was found that the proposition had carried by a vote of almost two to one and on April 10, 1878, another was passed providing for an issue of bonds amounting to $110,000, due in twenty years, with interest at the rate of eight per cent per annum.