The Communal Landscape –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session of the Zionist General Council

SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1967 Addresses,; Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE n Library י»B I 3 u s t SESSION OF THE ZIONIST GENERAL COUNCIL THIRD SESSION AFTER THE 26TH ZIONIST CONGRESS JERUSALEM JANUARY 8-15, 1966 Addresses, Debates, Resolutions Published by the ORGANIZATION DEPARTMENT OF THE ZIONIST EXECUTIVE JERUSALEM iii THE THIRD SESSION of the Zionist General Council after the Twenty-sixth Zionist Congress was held in Jerusalem on 8-15 January, 1967. The inaugural meeting was held in the Binyanei Ha'umah in the presence of the President of the State and Mrs. Shazar, the Prime Minister, the Speaker of the Knesset, Cabinet Ministers, the Chief Justice, Judges of the Supreme Court, the State Comptroller, visitors from abroad, public dignitaries and a large and representative gathering which filled the entire hall. The meeting was opened by Mr. Jacob Tsur, Chair- man of the Zionist General Council, who paid homage to Israel's Nobel Prize Laureate, the writer S.Y, Agnon, and read the message Mr. Agnon had sent to the gathering. Mr. Tsur also congratulated the poetess and writer, Nellie Zaks. The speaker then went on to discuss the gravity of the time for both the State of Israel and the Zionist Move- ment, and called upon citizens in this country and Zionists throughout the world to stand shoulder to shoulder to over- come the crisis. Professor Andre Chouraqui, Deputy Mayor of the City of Jerusalem, welcomed the delegates on behalf of the City. -

İSRAİL ISO 9001 BELGESİ VE FİYATI Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Standardı' Nın Hazırlanışı Mantalite Ve Metodoloji

İSRAİL ISO 9001 BELGESİ VE FİYATI Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Standardı’ nın hazırlanışı mantalite ve metodoloji olarak belirli coğrafyaları içerecek şekilde olmamaktadır. ISO-Uluslararası Standart Organizasyonu standartları global kullanım amaçlı hazırlamakta ve bu standartlarla küresel bir standart yapısı kurmayı hedeflemektedir. Bu hedefle kullanıma sunulan uluslararası kalite yönetim sistemi standardının tüm dünyada kriteri ve uygulaması aynı fakat standart dili farklıdır. ISO 9001 Kalite Yönetim Sistemi Belgesi ve fiyatının uygulama kriteri İSRAİL Ülkesi ve şehirlerin de tamamen aynıdır. Ancak her kuruluşun maliyet ve proses yapıları farklı olduğu için standart uygulaması ne kadar aynı da olsa fiyatlar farklılık göstermektedir. İSRAİL Ülkesinde kalite yönetim sistemi uygulaması ve standart dili İSRAİLca olarak uyarlanmıştır. İSRAİL Standart Kurumunun, standardı İSRAİL diline uyarlaması ile bu ülke bu standardı kabul etmiş, ülke coğrafyasında yer alan tüm şehirler ve kuruluşları için kullanımına sunmuştur. İSRAİL ISO 9001 belgesi ve fiyatı ilgili coğrafi konum olarak yerleşim yerleri ve şehirleri ile ülke geneli ve tüm dünya genelinde geçerli, kabul gören ve uygulanabilir bir kalite yönetim sistemi standardı olarak aşağıda verilen şehirleri, semtleri vb. gibi tüm yerel yapısında kullanılmaktadır. ISQ-İntersistem Belgelendirme Firması olarak İSRAİL ülkesinin genel ve yerel coğrafyasına hitap eden global geçerli iso 9001 belgesi ve fiyatı hizmetlerini vermekte olduğumuzu kullanıcılarımızın bilgisine sunmaktayız. İSRAİL ISO 9001 belgesi fiyatı ISQ belgelendirme yurt dışı standart belge fiyatı ile genellikle aynıdır. Ancak sadece denetçi(ler) yol, konaklama ve iaşe vb. masrafı fiyata ilave edilebilir. Soru: İSRAİL ’ daki ISO 9001 ile başka ülkelerdeki ISO 9001 aynı mıdır? Cevap: Evet. Uluslararası iso 9001 standardı Dünya’ nın her yerinde aynıdır, sadece fiyatları değişiklik gösterir. Ülke coğrafyasının büyüklüğü, nüfusu, sosyal yapısı vb. -

Shadows Over the Land Without Shade: Iconizing the Israeli Kibbutz in the 1950S, Acting-Out Post Palestinian-Nakba Cultural Trauma

Volume One, Number One Shadows over the Land Without Shade: Iconizing the Israeli Kibbutz in the 1950s, acting-out post Palestinian-Nakba Cultural Trauma Lior Libman Abstract: The kibbutz – one of Zionism's most vital forces of nation-building and Socialist enterprise – faced a severe crisis with the foundation of the State of Israel as State sovereignty brought about major structural, political and social changes. However, the roots of this crisis, which I will describe as a cultural trauma, are more complex. They go back to the pioneers' understanding of their historical action, which emanated arguably from secularized and nationalized Hasidic theology, and viewed itself in terms of the meta-historical Zionist-Socialist narrative. This perception was no longer conceivable during the 1948 war and thereafter. The participation in a war that involved expulsion and killing of civilians, the construction of new kibbutzim inside emptied Palestinian villages and confiscation by old and new kibbutzim of Palestinian fields, all caused a fatal rift in the mind of those who saw themselves as fulfilling a universal humanistic Socialist model; their response was total shock. This can be seen in images of and from the kibbutz in this period: in front of a dynamic and troublesome reality, the Realism of kibbutz-literature kept creating pastoral-utopian, heroic-pioneering images. The novel Land Without Shade (1950) is one such example. Written by the couple Yonat and Alexander Sened, it tells the story of the establishment of Kibbutz Revivim in the Negev desert in the 1940s. By a symptomatic reading of the book’s representation of the kibbutz, especially in relation to its native Bedouin neighbors and the course of the war, I argue that the iconization of the kibbutz in the 1950s is in fact an acting-out of the cultural trauma of the kibbutz, the victimizer, who became a victim of the crash of its own self-defined identity. -

6-194E.Pdf(6493KB)

Samuel Neaman Eretz Israel from Inside and Out Samuel Neaman Reflections In this book, the author Samuel (Sam) Neaman illustrates a part of his life story that lasted over more that three decades during the 20th century - in Eretz Israel, France, Syria, in WWII battlefronts, in Great Britain,the U.S., Canada, Mexico and in South American states. This is a life story told by the person himself and is being read with bated breath, sometimes hard to believe but nevertheless utterly true. Neaman was born in 1913, but most of his life he spent outside the country and the state he was born in ERETZ and for which he fought and which he served faithfully for many years. Therefore, his point of view is from both outside and inside and apart from • the love he expresses towards the country, he also criticizes what is going ERETZ ISRAELFROMINSIDEANDOUT here. In Israel the author is well known for the reknowned Samuel Neaman ISRAEL Institute for Advanced Studies in Science and Technology which is located at the Technion in Haifa. This institute was established by Neaman and he was directly and personally involved in all its management until he passed away a few years ago. Samuel Neaman did much for Israel’s security and FROM as a token of appreciation, all IDF’s chiefs of staff have signed a a megila. Among the signers of the megila there were: Ig’al Yadin, Mordechai Mak- lef, Moshe Dayan, Haim Laskov, Zvi Zur, Izhak Rabin, Haim Bar-Lev, David INSIDE El’arar, and Mordechai Gur. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. The exact Hebrew name for this affair is the “Yemenite children Affair.” I use the word babies instead of children since at least two thirds of the kidnapped were in fact infants. 2. 1,053 complaints were submitted to all three commissions combined (1033 complaints of disappearances from camps and hospitals in Israel, and 20 from camp Hashed in Yemen). Rabbi Meshulam’s organization claimed to have information about 1,700 babies kidnapped prior to 1952 (450 of them from other Mizrahi ethnic groups) and about 4,500 babies kidnapped prior to 1956. These figures were neither discredited nor vali- dated by the last commission (Shoshi Zaid, The Child is Gone [Jerusalem: Geffen Books, 2001], 19–22). 3. During the immigrants’ stay in transit and absorption camps, the babies were taken to stone structures called baby houses. Mothers were allowed entry only a few times each day to nurse their babies. 4. See, for instance, the testimony of Naomi Gavra in Tzipi Talmor’s film Down a One Way Road (1997) and the testimony of Shoshana Farhi on the show Uvda (1996). 5. The transit camp Hashed in Yemen housed most of the immigrants before the flight to Israel. 6. This story is based on my interview with the Ovadiya family for a story I wrote for the newspaper Shishi in 1994 and a subsequent interview for the show Uvda in 1996. I should also note that this story as well as my aunt’s story does not represent the typical kidnapping scenario. 7. The Hebrew term “Sephardic” means “from Spain.” 8. -

Israeli Cows Are Taking Over the World

Israeli Cows are Taking Over the World Sara Toth Stub Israel’s high-tech expertise is being applied to milk and cheese. Dairy farmers from India to Italy are learning how to increase their yields by traveling to kibbutzim. And that’s no bull. On a recent hot afternoon, a group of farmers from around the world wandered through the cow barns at Kibbutz Afikim, an agricultural cooperative founded by Jewish immigrants from Russia in 1924. It was late June in the Jordan Valley; the temperature spiked at 90 degrees. But the delegation of farmers had just asked to leave an air-conditioned conference room and use their limited time to see the cow barns. Despite the high temperatures, the nearly 900 cows were calm, many lying in the mud that covers the floor of their barns, which are partly open to the outside and cooled by large fans. These barns at Afikim, and Israeli milk cows in general, are a growing attraction for visitors as Israel’s dairy industry has emerged as one of the most efficient and productive in the world. Despite limited rainfall and high summer temperatures, Israel has the highest national average of milk production per cow. And amid the fast-growing global demand for dairy products, especially in the developing world, there is increasing interest in how Israel gets so much milk out of each cow and the technology it uses to do so. “Happy cows give a lot of milk. People from around the world are coming here, and they see that it’s terribly hot, but that the cows are happy,” said Ofier Langer, a former executive at several Israeli high-tech companies who established the Israeli Dairy School six years ago. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2005 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service ► The o rganization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state re porting requirements. A For the 2005 calendar year , or tax year be and B Check If C Name of organization D Employer Identification number applicable Please use IRS change ta Qachange RICA IS RAEL CULTURAL FOUNDATION 13-1664048 E; a11gne ^ci See Number and street (or P 0. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 0jretum specific 1 EAST 42ND STREET 1400 212-557-1600 Instruo retum uons City or town , state or country, and ZIP + 4 F nocounwro memos 0 Cash [X ,camel ded On° EW YORK , NY 10017 (sped ► [l^PP°ca"on pending • Section 501 (Il)c 3 organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trusts H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations. must attach a completed Schedule A ( Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates ? Yes OX No G Website : : / /AICF . WEBNET . ORG/ H(b) If 'Yes ,* enter number of affiliates' N/A J Organization type (deckonIyone) ► [ 501(c) ( 3 ) I (insert no ) ] 4947(a)(1) or L] 527 H(c) Are all affiliates included ? N/A Yes E__1 No Is(ITthis , attach a list) K Check here Q the organization' s gross receipts are normally not The 110- if more than $25 ,000 . -

Aufstände in Galiläa

Online-Texte der Evangelischen Akademie Bad Boll Aufstände in Galiläa Schriftliche Berichte und archäologische Funde Dr. Yinon Shivtiel Ein Beitrag aus der Tagung: Bauern, Fischer und Propheten. Neues aus Galiläa zur Zeit Jesu Archäologie und Theologie im Neuen Testament Bad Boll, 7. - 8. Mai 2011, Tagungsnummer: 500211 Tagungsleitung: Dr. Thilo Fitzner _____________________________________________________________________________ Bitte beachten Sie: Dieser Text ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers/der Urheberin bzw. der Evangelischen Akade- mie Bad Boll. © 2011 Alle Rechte beim Autor/bei der Autorin dieses Textes Eine Stellungnahme der Evangelischen Akademie Bad Boll ist mit der Veröffentlichung dieses Textes nicht ausge- sprochen. Evangelische Akademie Bad Boll Akademieweg 11, D-73087 Bad Boll E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.ev-akademie-boll.de Cliff Settlements, Shelters and Refuge Caves in the Galilee1 Yinon Shivtiel2 The1existence of intricate systems of intercon- nected refuge caves in2the Judean Desert has been known for a long time, and has been the subject of many publications, including one in this volume.3 These systems were attributed by researchers to the period of the Bar Kokhba rebellion. One of the researchers suggested in his article that over 20 similar systems existed in the Galilee (Shahar 2003, 232-235). The pur- pose of this article is to show that the cave sys- tems in the Galilee served not only as places Figure 1. Two coins from Akhbarah. of refuge, but also as escape routes for local villagers. The common denominator of these the time-range and the simultaneity of prepa- systems was their complexity, as compared rations of the caves for refuge suggest that the with cliff-top caves, as they are currently acces- methods of enlarging and preparing these caves sible only by rappelling. -

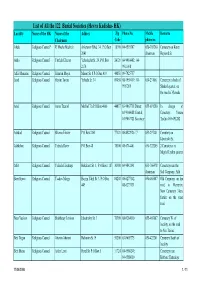

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5

Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5 Article 8 2013 Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5 Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Scholarship, Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious (2013) "Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5," Studies in the Bible and Antiquity: Vol. 5 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sba/vol5/iss1/8 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in the Bible and Antiquity by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Editor Brian M. Hauglid Associate Editor Carl Griffin Production Editor Shirley S. Ricks Cover Design Jacob D. Rawlins Typesetting Melissa Hart Advisory Board David E. Bokovoy John Gee Frank F. Judd Jr. Jared W. Ludlow Donald W. Parry Dana M. Pike Thomas A. Wayment Studies in the Bible and Antiquity Volume 5 • 2013 Studies in the Bible and Antiquity is dedicated to promoting a better understanding of the Bible and of religion in the ancient world, bringing the best LDS scholarship and thought to a general Latter- day Saint readership. Questions may be directed to the editors at [email protected]. © 2013 Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Phone: (801) 422-9229 Toll Free: (800) 327-6715 FAX: (801) 422-0040 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/publications/studies ISSN 2151-7800 (print), 2168-3166 (online) Contents Introduction vii Finding Samson in Byzantine Galilee: The 2011-2012 Archaeological Excavations at Huqoq Matthew J. -

Biometric Growth and Behavior of Calf-Fed Holstein Steers Fed in Confinement

BIOMETRIC GROWTH AND BEHAVIOR OF CALF-FED HOLSTEIN STEERS FED IN CONFINEMENT By Jacob A. Reed B.S., Texas A&M University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Major Subject: Animal Science West Texas A&M University Canyon, Texas July 2015 ABSTRACT The objective of this research was to determine the impact of zilpaterol hydrochloride (ZH) on movement behavior of calf-fed Holstein steers fed in confinement as well as understand the optimal slaughter end point for a calf-fed Holstein by use of biometric measurements. Calf-fed Holstein steers (n = 135) were randomized to 11 pre- assigned slaughter groups (254, 282, 310, 338, 366, 394, 422, 450, 478, 506, and 534 days on feed) consisting of 10 steers per group. Steers were assigned to one of three pens each containing a feed behavior and disappearance system (GrowSafe, Airdrie, AB Canada) which had four feed nodes per pen. A fourth terminal pen was divided in half with one side containing five steers fed a ration supplemented with ZH and the other half containing five steers fed a control ration without ZH supplementation. Steers placed in the fourth terminal pen were fed in 28 d feeding periods; d 1 to 5 included no ZH supplementation, d 6 to 25 included ZH (8.33 mg/kg dietary DM) supplementation, and steers were withdrawn from ZH during d 26 to 28. Objective movement behavior of each animal was monitored during the 28 d prior to harvest using an accelerometer (IceQube, IceRobotics, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK) attached to the left hind leg of each animal. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District.