Status and Distribution of Alaska Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forage Fishes of the Southeastern Bering Sea Conference Proceedings

a OCS Study MMS 87-0017 Forage Fishes of the Southeastern Bering Sea Conference Proceedings 1-1 July 1987 Minerals Management Service Alaska OCS Region OCS Study MMS 87-0017 FORAGE FISHES OF THE SOUTHEASTERN BERING SEA Proceedings of a Conference 4-5 November 1986 Anchorage Hilton Hotel Anchorage, Alaska Prepared f br: U.S. Department of the Interior Minerals Management Service Alaska OCS Region 949 East 36th Avenue, Room 110 Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4302 Under Contract No. 14-12-0001-30297 Logistical Support and Report Preparation By: MBC Applied Environmental Sciences 947 Newhall Street Costa Mesa, California 92627 July 1987 CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................. iv INTRODUCTION PAPERS Dynamics of the Southeastern Bering Sea Oceanographic Environment - H. Joseph Niebauer .................................. The Bering Sea Ecosystem as a Predation Controlled System - Taivo Laevastu .... Marine Mammals and Forage Fishes in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Kathryn J. Frost and Lloyd Lowry. ............................. Trophic Interactions Between Forage Fish and Seabirds in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Gerald A. Sanger ............................ Demersal Fish Predators of Pelagic Forage Fishes in the Southeastern Bering Sea - M. James Allen ................................ Dynamics of Coastal Salmon in the Southeastern Bering Sea - Donald E. Rogers . Forage Fish Use of Inshore Habitats North of the Alaska Peninsula - Jonathan P. Houghton ................................. Forage Fishes in the Shallow Waters of the North- leut ti an Shelf - Peter Craig ... Population Dynamics of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii), Capelin (Mallotus villosus), and Other Coastal Pelagic Fishes in the Eastern Bering Sea - Vidar G. Wespestad The History of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) Fisheries in Alaska - Fritz Funk . Environmental-Dependent Stock-Recruitment Models for Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) - Max Stocker. -

Effects of Nestling Diet on Growth and Adult Size of Zebra Finches (Poephila Guttata )

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 104 APRIL 1987 NO. 2 EFFECTS OF NESTLING DIET ON GROWTH AND ADULT SIZE OF ZEBRA FINCHES (POEPHILA GUTTATA ) PETER T. BOAG Departmentof Biology,Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada Al•STRACT.--Manipulationof the diet of Zebra Finch (Poephilaguttata) nestlings in the laboratoryshowed that a low-quality diet reducedgrowth ratesof nine externalmorpholog- ical characters,while a high-quality diet increasedgrowth rates.The growth of plumage characterswas least affectedby diet, while growth ratesof tarsusand masswere most af- fected. The treatments also produced differencesin the adult size of experimental birds, differencesnot evident in either their parentsor their own offspring.Diet quality had the strongestimpact on adult massand tarsuslength, while plumage and beak measurements were less affected. Analysis using principal componentsand characterratios showed that the shapeof experimentalbirds was affectedby the experimentaldiets, but to a minor extent comparedwith changesin overall size. Significantshape changes involved ratiosbetween fast- and slow-growingcharacters. The ratios of charactersthat grow at similar, slow rates (e.g. beak shape) were not affected by the diets. Environmental sourcesof morphological variation should not be neglectedin studiesof phenotypicvariation in birds. Received5 June 1986, accepted30 October1986. MORPHOLOGICAL differences between indi- fitness, and weather was seen in the nonran- vidual birds are often assignedfunctional sig- dom survival of House Sparrows collected by nificance, whether those individuals are of dif- Hiram Bumpus following a winter storm ferent species,different sexes,or different-size (O'Donald 1973, Fleischer and Johnston 1982). members of the same sex (Hamilton 1961, Se- Recently, investigators have tried to dem- lander 1966,Clark 1979,James 1982). -

Alaska Region Revised 2020

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History Repatriation Office Case Report Summaries Alaska Region Revised 2020 Alaska Alutiiq, Koniag, 1991 LARSEN BAY, KODIAK ISLAND Yu'pik In September 1991, the NMNH repatriated the human remains of approximately 1000 individuals from the Uyak (KOD-145) archaeological site to the Alaska Native village of Larsen Bay, and 144 funerary objects were repatriated in January 1992. The museum had received a request to repatriate these remains and artifacts in 1987, and a series of communications between the village and the Smithsonian resulted in the decision to repatriate the remains as culturally affiliated with the present day people of Larsen Bay. The burials had been excavated by a Smithsonian curator, Ales Hrdlicka, during a series of excavations in the 1930s, and dated from around 1000 B.C. to post-contact times. No report is available, but information on the site and the repatriation may be found in the following book: Reckoning With the Dead: the Larsen Bay Repatriation and the Smithsonian Institution. Edited by Tamara L. Bray and Thomas W. Killion. Published in 1994 by the Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. Alaska Inupiat, Yu'pik, 1994 INVENTORY AND ASSESSMENT OF HUMAN REMAINS AND NANA Regional ASSOCIATED FUNERARY OBJECTS FROM NORTHEAST NORTON Corporation SOUND, BERING STRAITS NATIVE CORPORATION, ALASKA IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY This report provides a partial inventory and assessment of the cultural affiliation of the human remains and funerary objects in the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) from within the territorial boundaries of the Bering Strait Native Corporation. -

Prehistoric Aleut Influence at Port Moller

12 'i1 Pribilof lis. "' Resale for so 100 150 200 ·o oO Miles .,• t? 0 Not Fig. 1. Map of the Alaska Peninsula and Adjacent Areas. The dotted line across the Peninsula represents the Aleut boundary as determined by Petroff. Some of the important archaeological sites are marked as follows: 1) Port Moller, 2) Amaknak Island-Unalaska Bay, 3) Fortress or Split Rock, 4) Chaluka, 5) Chirikof Island, 6) Uyak, 7) Kaflia, 8) Pavik-Naknek Drainage, 9) Togiak, 10) Chagvan Bay, 11) Platinum, 12) Hooper Bay. PREHISTORIC ALEUT INFLUENCES AT PORT MOLLER, ALASKA 1 by Allen P. McCartney Univ. of Wisconsin Introduction Recent mention has been made of the Aleut influences at the large prehistoric site at Port Moller, the only locality known archaeologically on the southwestern half of the Alaska Penin sula. Workman ( 1966a: 145) offers the following summary of the Port Moller cultural affinities: Although available published material from the Aleutians is scarce and the easternmost Aleutians in particular have been sadly neglected, it is my opinion that the strongest affinitiesResale of the Port Moller material lie in this direction. The prevalence of extended burial and burial association with ocher at Port Moller corresponds most closely with the burial practices at the Chaluka site on Umnak Island. Several of the more diagnostic projectile points have Aleutian affinities as do the tanged knives and, possibly,for the side-notched projectile point. Strong points of correspondence, particularly in the burial practices and the stone technology, lead me to believe that a definite Aleut component is represented at the site. Data currently available will not allow any definitive statement as to whether or not there are other components represented at the site as well. -

Fishery Management Plan for Arctic Grayling Sport Fisheries Along the Nome Road System, 2001–2004

Fishery Management Report No. 02-03 Fishery Management Plan for Arctic Grayling Sport Fisheries along the Nome Road System, 2001–2004 by Fred DeCicco April 2002 Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Sport Fish Symbols and Abbreviations The following symbols and abbreviations, and others approved for the Système International d'Unités (SI), are used in Division of Sport Fish Fishery Manuscripts, Fishery Data Series Reports, Fishery Management Reports, and Special Publications without definition. Weights and measures (metric) General Mathematics, statistics, fisheries centimeter cm All commonly accepted e.g., Mr., Mrs., alternate hypothesis HA deciliter dL abbreviations. a.m., p.m., etc. base of natural e gram g All commonly accepted e.g., Dr., Ph.D., logarithm hectare ha professional titles. R.N., etc. catch per unit effort CPUE kilogram kg and & coefficient of variation CV at @ 2 kilometer km common test statistics F, t, , etc. liter L Compass directions: confidence interval C.I. meter m east E correlation coefficient R (multiple) north N metric ton mt correlation coefficient r (simple) milliliter ml south S covariance cov millimeter mm west W degree (angular or ° Copyright temperature) Weights and measures (English) Corporate suffixes: degrees of freedom df cubic feet per second ft3/s Company Co. divided by ÷ or / (in foot ft Corporation Corp. equations) gallon gal Incorporated Inc. equals = inch in Limited Ltd. expected value E mile mi et alii (and other et al. fork length FL ounce oz people) greater than > O pound lb et cetera (and so forth) etc. greater than or equal to quart qt exempli gratia (for e.g., harvest per unit effort HPUE example) yard yd less than < id est (that is) i.e., ? less than or equal to latitude or longitude lat. -

Pamphlet to Accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3131

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Seward Peninsula, Alaska, and Accompanying Conodont Data By Alison B. Till, Julie A. Dumoulin, Melanie B. Werdon, and Heather A. Bleick Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3131 View of Salmon Lake and the eastern Kigluaik Mountains, central Seward Peninsula 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................1 Sources of data ....................................................................................................................................1 Components of the map and accompanying materials .................................................................1 Geologic Summary ........................................................................................................................................1 Major geologic components ..............................................................................................................1 York terrane ..................................................................................................................................2 Grantley Harbor Fault Zone and contact between the York terrane and the Nome Complex ..........................................................................................................................3 Nome Complex ............................................................................................................................3 -

Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS

VOLUME 1. MARINE MAMMALS, MARINE BIRDS VOLUME 2, FISH, PLANKTON, BENTHOS, LITTORAL VOLUME 3, EFFECTS, CHEMISTRY AND MICROBIOLOGY, PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 4. GEOLOGY, ICE, DATA MANAGEMENT Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf July - Sept 1976 quarterly reports from Principal Investigators participatingin a multi-year program of environmental assessment related to petroleum development on the Alaskan Continental Shelf. The program is directed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the sponsorship of the Bureau of Land Management. ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LABORATORIES Boulder, Colorado November 1976 VOLUME 1 CONTENTS MARINE MAMMALS vii MARINE BIRDS 167 iii MARINE MAMMALS v MARINE MAMMALS Research Unit Proposer Title Page 34 G. Carleton Ray Analysis of Marine Mammal Remote 1 Douglas Wartzok Sensing Data Johns Hopkins U. 67 Clifford H. Fiscus Baseline Characterization of Marine 3 Howard W. Braham Mammals in the Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS 68 Clifford H. Fiscus Abundance and Seasonal Distribution 30 Howard W. Braham of Marine Mammals in the Gulf of Roger W. Mercer Alaska NWFC/NMFS 69 Clifford H. Fiscus Distribution and Abundance of Bowhead 33 Howard W. Braham and Belukha Whales in the Bering Sea NWFC/NMFS 70 Clifford H. Fiscus Distribution and Abundance of Bow- 36 Howard W. Braham et al head and Belukha Whales in the NWFC/NMFS Beaufort and Chukchi Seas 194 Francis H. Fay Morbidity and Mortality of Marine 43 IMS/U. of Alaska Mammals 229 Kenneth W. Pitcher Biology of the Harbor Seal, Phoca 48 Donald Calkins vitulina richardi, in the Gulf of ADF&G Alaska 230 John J. Burns The Natural History and Ecology of 55 Thomas J. -

Aleuts: an Outline of the Ethnic History

i Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Roza G. Lyapunova Translated by Richard L. Bland ii As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has re- sponsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural and cultural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Shared Beringian Heritage Program at the National Park Service is an international program that rec- ognizes and celebrates the natural resources and cultural heritage shared by the United States and Russia on both sides of the Bering Strait. The program seeks local, national, and international participation in the preservation and understanding of natural resources and protected lands and works to sustain and protect the cultural traditions and subsistence lifestyle of the Native peoples of the Beringia region. Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History Author: Roza G. Lyapunova English translation by Richard L. Bland 2017 ISBN-13: 978-0-9965837-1-8 This book’s publication and translations were funded by the National Park Service, Shared Beringian Heritage Program. The book is provided without charge by the National Park Service. To order additional copies, please contact the Shared Beringian Heritage Program ([email protected]). National Park Service Shared Beringian Heritage Program © The Russian text of Aleuts: An Outline of the Ethnic History by Roza G. Lyapunova (Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo “Nauka” leningradskoe otdelenie, 1987), was translated into English by Richard L. -

Port of Nome Modification Feasibility Study Nome, Alaska

Draft Integrated Feasibility Report and Supplemental Environmental Assessment Port of Nome Modification Feasibility Study Nome, Alaska December 2019 This page left blank intentionally. Draft Integrated Feasibility Report and Supplemental Environmental Assessment Port of Nome Modification Feasibility Study Nome, Alaska Prepared by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Alaska District December 2019 This page left blank intentionally. Port of Nome Modification Feasibility Study Draft Integrated Feasibility Report and Supplemental Environmental Assessment EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This General Investigations study is being conducted under authority granted by Section 204 of the Flood Control Act of 1948, which authorizes a study of the feasibility for development of navigation improvements in various harbors and rivers in Alaska. This study is also utilizing the authority of Section 2006 of WRDA, 2007, Remote and Subsistence Harbors, as modified by Section 2104 of the Water Resources Reform and Development Act of 2014 (WRRDA 2014) and further modified by Section 1105 of WRDA 2016. Section 2006 states that the Secretary may recommend a project without demonstrating that the improvements are justified solely by National Economic Development (NED) benefits, if the Secretary determines that the improvements meet specific criteria detailed in the authority. Additionally, Section 1202(c)(3) of WRDA 2016 “Additional Studies, Arctic Deep Draft Port Development Partnerships” allows for the consideration of transportation cost savings benefits to national security. The proposed port modifications intend to improve navigation efficiency to reduce the costs of commodities critical to the viability of communities in the region. This study has been cost-shared, with 50 % of the study funding provided by the non-Federal sponsor, which is the City of Nome, per the Federal Cost Share Agreement. -

Digital Data for the Preliminary Bedrock Geologic Map of The

Open-File Report 2009-1254 U.S. Department of the Interior Sheet 2 of 2 U.S. Geological Survey Pamphlet accompanies map '02°761 '01°761 '00°761 LIST OF METAMORPHIC-TECTONIC ELEMENTS HIGH GRADE METAMORPHIC AND ASSOCIATED O<t Qs Ol Nome Complex, west-central – Weakly foliated metasedimentary O<l O<l IGNEOUS ROCKS – Amphibolite and granulite-facies O<l O<l Ol Ols Ols YORK TERRANE – Late Proterozoic (?) and Paleozoic sedimentary and unfoliated metaigneous rocks that retain relict primary features; and metasedimentary rocks and minor Late Cretaceous tin-bearing mineral assemblages in mafic rocks formed at pumpellyite-actinolite, metamorphic rocks and associated Cretaceous plutons; penetratively Qs greenschist, and blueschist facies (one locality) deformed metasedimentary and metaigneous schist and gneiss with Oal granites; dominantly carbonate and siliciclastic lithologies, in which Oal primary features are generally retained; fine-grained Nome Complex, eastern – Penetratively deformed and complex metamorphic histories; aluminum-rich lithologies show Ol early development of kyanite-stable mineral assemblages succeeded Ol 17 metasedimentary rocks are weakly foliated. Metamorphic and recrystallized schists with ductile fabrics; protolith packages and Ol Ols 165°00' by sillimanite-stable, lower-pressure assemblages. Lithologies rich in O<p Ols thermal history variable from unit to unit, and generally lower grade metamorphic fabrics identical to Nome Complex in central Seward Oal Qs Peninsula; mineral assemblages in most of the area are characteristic iron and aluminum retain early, relatively high pressure Ktg than Nome Complex. Tin granites intruded in shallow crustal Ols Ol aluminosilicate plus orthoamphibole assemblages (>5kb) that are Cape Espenberg settings. The generally brittle shallow and steeply-dipping structures of greenschist facies, but slightly higher grade assemblages occur in Ol the vicinity of Kiwalik Mountain. -

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

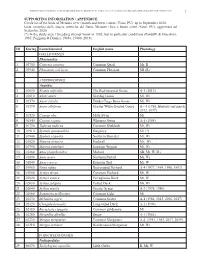

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P.