Copyright Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is-6 Ta' Novembru, 2019 24,001 This Is a List of Complete Applications

Is-6 ta’ Novembru, 2019 24,001 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sas-06 ta’ Diċembru, 2019. -

Official Program 2013

а 22-26 august ниј о д е к а ид, М ид, р Ohrid, Macedonia | Ох | Macedonia Ohrid, ohrid choir festival охридски хорски фестивал2013 2nd Competition Concert | 2. Натпреварувачки концерт FRIDAY | ПЕТОК Diamont Hall, Hotel Inex Gorica | Дијамантска Сала, Хотел Инекс Горица 19.00 - 19.15 Mixed Youth Choir “Josip Kaplan” - Croatia 19.15 - 19.30 Gdansk University Choir - Poland 1st Concert of Sacred Music | 1. Концерт на духовна музика 19.30 - 19.45 Choir of Maritime University of Szczecin - Poland Church of St. Sophia | Црква Св. Софија 19.45 - 20.00 Youth Choir of Šabac Singing Society - Serbia 10.00 - 10.10 The Academic Choir of Adam Mickiewicz University - Poland 10.10 - 10.20 The Bialystok Technical University Choir - Poland SATURDAY | САБОТА 10.20 - 10.30 Youth Choir “Canto” School of Music Czesław Niemen - Poland 10.30 - 10.40 Youth Female Chamber Choir “Cantilena” by the museum of school of K. May of Saint-Petersburg Institute of 3rd Competition Concert | 3. Натпреварувачки концерт Informatics and Automation of Russian Science Academy - Russia Diamont Hall, Hotel Inex Gorica | Дијамантска Сала, Хотел Инекс Горица 10.40 - 10.50 Chamber Choir of Bulgarian Academy of Science - Bulgaria 10.00 - 10.15 Children’s Chamber Choir “Solovushko” - Russia 10.50 - 11.00 Butelion Classics Chorus - Macedonia 10.15 - 10.30 “Saulainė” - Lithuania 10.30 - 10.45 Valmiera Music School Choir “SolLaRe” - Latvia 2nd Concert of Sacred Music | 2. Концерт на духовна музика 10.45 - 11.00 Break Church of St. Sophia | Црква Св. Софија 11.00 - 11.15 Children’s Choir “Trallala” - Czech Republic 11.30 - 11.40 Valmiera Music School Choir “SolLaRe” - Latvia 11.15 - 11.30 Children’s Choir “The Stars” - Serbia 11.40 - 11.50 Children’s Choir Pražská kantiléna - Czech Republic 11.50 - 12.00 Female vocal ensemble “Making waves” - Ukraine 4th Competition Concert | 4. -

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015/2016 Gwytha Ha Crefhe! 30 Years Preserving and Strengthening Our Cornish Heritage

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015/2016 Gwytha ha Crefhe! 30 years preserving and strengthening our Cornish heritage In the early 1980’s there was a growing concern that too much of the Cornish heritage was under threat from potential private buyers. Two such sites were Land’s End and Lamorna Cove and there was no organisation in Cornwall with the ability to raise the funds required to save the sites. On the 19th February 1983 a group of people got together with the idea of forming such an organisation with the aim of saving buildings, ancient artifacts and important heritage sites. It was the irst of regular meetings, held at the Royal Hotel in Truro, and the Oficers elected were Acting Chairman The Honourable Robert Eliot, Acting Vice Chairman Mrs June Lander, Secretary Mr John Menhinick, Assistant Secretary Mr Jack Spry and the Treasurer Mr Tim Le Grice. At the meeting it was unanimously agreed that Mr Kenneth Kendall be elected as the irst Patron. Subsequent meetings eventually resulted in the Our Education portfolio includes projects with Primary appointments of The Honourable Robert Eliot as Chairman schools and the funding of transport for class visits to with Mrs Moira Tangye as Vice Chairman, The Hon. Treasurer heritage sites which many schools are taking advantage of Mr Carl Roberts and The Hon. Secretary Mr John Menhinick. due to the dificulty of funding in this area. Mr Jack Spry became the Membership Secretary and a We award bursaries to post graduate students who are solicitor, Mr Robin Bailey, was also appointed. So on the studying Cornish history, and in this we work very closely with 2nd April 1985 the Cornwall Heritage Trust came into being, the Institute of Cornish Studies and Exeter University. -

Tappard Farm Barns Deveral Road, Fraddam, Hayle, Cornwall Tr27 5Ep

Ref: LAT210022 GUIDE PRICE: £295,000 A Prime Development Opportunity in Rural Surroundings TAPPARD FARM BARNS DEVERAL ROAD, FRADDAM, HAYLE, CORNWALL TR27 5EP A collection of former farm barns with residential planning consent to create a small and appealing development of three homes together with additional sheds ideal for storage with possible further potential. Tucked away on the rural fringes of popular West Cornwall villages, this sheltered location is easily accessible to the nearby towns of Hayle and Helston. HAYLE (A30) 3.5 MILES * HELSTON 7 MILES * CAMBORNE 5 MILES TRURO 22 MILES * FALMOUTH 17 MILES SITUATION Barely a minute from the B3302 Hayle to Helston Road, this is an extremely central and convenient setting hidden away from most day to day hustle and bustle. The communities of Fraddam, Reawla, Wall, Carnhell Green and Leedstown are all within a 3 mile radius. There is a Post Office/grocery store in Carnhell Green with a more extensive range of shops, doctors’ surgery, dentists and a hospital less than 4 miles away within the north coastal harbour town of Hayle which also boasts a choice of supermarkets and a retail park with Marks & Spencer and Boots etc. The County’s main arterial route, the A30, bypasses Hayle providing easy access to Penzance in the west and the City of Truro in the east and the town also has a station on the main Penzance to Paddington railway line. THE BARNS A courtyard of former farm barns and sheds with Conditional Planning Permission (PA18/03716) for residential conversion into three character homes. Additional useful buildings would be ideal for general storage of building materials and/or vehicles and equipment etc, and may also present potential for alternative use, subject to planning consent. -

80B Torpoint - Seaton - Liskeard

80B Torpoint - Seaton - Liskeard A Line Travel Timetable Valid from 14/01/2013 Until Further Notice Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch SH Torpoint, Torpoint Ferry (SW-bound) 0655 1007 1220 1510 1528 1810 Torpoint, Carbeile Inn (W-bound) 1008 1222 1522 1530 1812 Torpoint, School (NW-bound) 0658 1530 Torpoint, opp Torpoint Bus Depot 1531 Torpoint, HMS Raleigh (W-bound) 0700 1012 1225 1533 1533 1815 Antony, Ring O' Bells (W-bound) 0703 1015 1228 1536 1536 1818 Sheviock, Opposite Sheviock Church (NW-bound) 0706 1018 1231 1539 1539 1821 Polbathic, West Park (W-bound) 0709 Crafthole, opp Cross Park 1021 1234 1542 1542 1824 Portwrinkle, Finnygook Beach (E-bound) 1024 1237 1545 1545 1827 Downderry, opp Church 1037 1250 1558 1558 1838 Seaton, opp The Car Park 1040 1253 1601 1601 1841 Hessenford, Opposite the Old Mill (W-bound) 1046 1259 1607 1607 1847 Widegates, Antiques Shop (W-bound) 1050 1302 1610 1610 1850 Liskeard, Charter Way Morrisons (NE-bound) 1100 1312 1620 1620 Liskeard, Hospital (S-bound) 1103 1315 1623 1623 Liskeard, Post Office (S-bound) 0735 1106 1318 1626 1626 1900 Liskeard, opp Railway Station 1110 1321 1629 1629 1903 Saturdays Torpoint, Torpoint Ferry (SW-bound) 0655 1007 1220 1528 1810 Torpoint, Carbeile Inn (W-bound) 1008 1222 1530 1812 Torpoint, School (NW-bound) 0658 Torpoint, opp Torpoint Bus Depot Torpoint, HMS Raleigh (W-bound) 0700 1012 1225 1533 1815 Antony, Ring O' Bells (W-bound) 0703 -

CORNWALL Hender W. St. Thomas Hill, Launceston Hicks S

190 CORNWALL POST FARMERs-continued. Hender W. St. Thomas hill, Launceston Hicks S. Lewanick, Launceston Hawken G.L. Dannonchapple,f:t.Teath, Hendy A. Trebell, Lanivet, Bodmin Hicks T. Carn, Lelant, Hay le Camelford Hendy E. Trebell, Lanivet, Bodmin Hicks T. Chynalls, St. Paul, Penzance Hawken H. Trefresa, Wadebridge Hendy H. Carmina, Mawgan, Helston Hicks T. Sancreed, Peuzance *Haw ken J.Penrose,St.Ervan, Padstow Hendy J. Trethurffe, Ladock,Grmpound Hicks T. Prideaux, Luxulion, Bodmin Hawken J. Treginnegar, Padstow Hendy J. Frogwell, Callington Hicks T. St. Autbony, Tre~ony HawkenJ.Treburrick,St.Ervan,Padstow Hendy J. Skewes, Cury, Helston Hicks T. Lanivet, Bodmin Haw ken J. jun. Penro~e, Pads tow Hendy J. Frowder, Mullion, Helston Hick;~ T. St. Gerrans, Gram pound Hawken N. Treore, Wadebridge Hendy M. Swyna, Gunwallot>, Helston Hicks T. St. Gennys, Camt>lford Haw ken P. Longcarne, Camelt'ord Hendy S. GunwalloP, Helston Hicks T.jun. Tregarneer,St.Colmb.Major Haw ken P.Tre~wyn, St. Ervan,Padstow Hendy T. Lizard, Helston Hicks W. Clift' farm, Anthony Haw ken R. Stanon,St.Breward, Bodmin Hendy W. Chimber, Gunwalloe,Helston Hicks W. St. Agnes, Scilly HawkenR.G.Trt-gwormond,Wadebrilige Hendy W. Mullion, Ht-lston Hicks W. Newlyn East, Grampound HawkenS.Low.Nankelly,St.ColumhMjr Ht>ndy W. PolJ(reen, Cury, Helston Hicks W. PencrebPr farm, Caliington Hawken T. Hale, St. Kew, Wadebridge Hendy W. Polgreen,Gunwalloe, Helston Hicks W. Fowey, Lostwithiel Haw ken T. Heneward, Bolimin Hermah H. Penare, Gorran, St. A ustell Hicks W. St. Agnes, Scilly Haw ken T. Trevorrick, St.lssry ,Bodmin Hennah T. -

FRG-Pack-Updated-Feb 20

www.facebook.com/cornwallhospicecare www.twitter.com/cornwallhospice www.cornwallhospicecare.co.uk 01726 66868 Dear Supporter, Thank you for your interest in provide at Mount Edgcumbe supporting the work of Cornwall Hospice in St Austell and St Julia’s Hospice Care. Your support Hospice in Hayle, your support is crucial in helping us to raise will allow us to give more people the £5 million that we need each the specialist support they so year to continue providing desperately need. Specialist Palliative Care for the Don’t be put off if you have never people of Cornwall. organised an event before - there You can make a real contribution are some handy tips and ideas to the future of the adult hospices, in this guide, and we are always and help us to build and expand available to offer more in depth the dedicated care that we advice and support. There are provide. With ever increasing also lots of event ideas to inspire demand on the services we you, or you may already have your own ideas on how to help us raise funds...We’d love to hear them! The Fundraising Team 01726 66868 (St Austell Office) 01736 755770 (Hayle Office) About Cornwall Hospice Care ornwall Hospice Care is a 24/7 Complementary Therapists and CCornish Charity that provides Bereavement Counsellors. specialist care for people with terminal illnesses. It costs over £5 million to provide the Our nursing teams support patients specialist care we offer to our in and and their families at Mount out patients. Only 20% of this is Edgcumbe Hospice in St Austell, St funded through a contribution from 500 Julia's Hospice in Hayle and in Cornwall’s NHS Commissioners. -

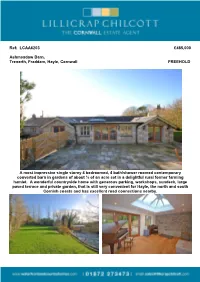

Ref: LCAA6203 £485,000

Ref: LCAA6203 £485,000 Ashmeadow Barn, Trenerth, Fraddam, Hayle, Cornwall FREEHOLD A most impressive single storey 4 bedroomed, 4 bath/shower roomed contemporary converted barn in gardens of about ⅓ of an acre set in a delightful rural former farming hamlet. A wonderful countryside home with generous parking, workshops, sundeck, large paved terrace and private garden, that is still very convenient for Hayle, the north and south Cornish coasts and has excellent road connections nearby. 2 Ref: LCAA6203 SUMMARY OF ACCOMMODATION Entrance hall, kitchen/dining room, living room, summer sitting room, utility, long inner hall, 4 bedrooms (2 en-suite), contemporary wet shower room, family bath/shower room. Outside: About ⅓ of an acre of mostly very private lawned gardens with a large terrace, sundeck and growing beds. Very large modern timber workshop, carport, glasshouse and garden shed plus two generous parking areas. DESCRIPTION Converted in 2001 and greatly updated and extended since Ashmeadow Barn is a very attractive granite and random stone faced extensive single story barn conversion in a rural but not isolated former farming hamlet. Inside there are four double bedrooms, two of which are en-suite, and there is also a family bathroom and separate 3 Ref: LCAA6203 contemporary wet shower room with three of these facilities having under floor heating. These rooms and an excellent utility serve a kitchen/dining room which opens through to a cosy living room with woodburning stove and there is also a further large reception room with bi-fold doors to the rear garden and a glass atrium filling it with light. -

A Study of Nones in Brazil and the USA in Light of Secularization Theory with Missiological Implications

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2020 A Study of Nones in Brazil and the USA in Light of Secularization Theory with Missiological Implications Jolive R. Chavez Andrews University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Chavez, Jolive R., "A Study of Nones in Brazil and the USA in Light of Secularization Theory with Missiological Implications" (2020). Dissertations. 1745. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/1745 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A STUDY OF NONES IN BRAZIL AND THE USA IN LIGHT OF SECULARIZATION THEORY, WITH MISSIOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS by Jolive R. Chaves Adviser: Gorden R. Doss ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological SeMinary Title: A STUDY OF NONES IN BRAZIL AND THE USA IN LIGHT OF SECULARIZATION THEORY, WITH MISSIOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS NaMe of researcher: Jolivê R. Chaves NaMe and degree of faculty adviser: Gorden R. Doss, PhD Date completed: NoveMber 2020 The growth of those who declare theMselves to be Nones, or religiously unaffiliated, in Brazil and the USA has been continuously higher than that of the general population. In Brazil, they are the third-largest group in the religious field, behind only Catholics, and Pentecostal evangelicals. In the USA, they are the second largest group, after Protestants as a whole. -

Fish Terminologies

FISH TERMINOLOGIES Monument Type Thesaurus Report Format: Hierarchical listing - class Notes: Classification of monument type records by function. -

Annual Review 2009-10 a Annual Review R

arts council ofA northern ireland annualR review 2009-10 annual review page 1 page Arts Council of Northern Ireland - 2009-10 www.artscouncil-ni.org arts council of northern ireland annual review 2009-10 arts council of northern ireland annual review 2009-10 page 2 page page 3 page Our Vision Our vision is to ‘place the arts at the heart of our social, economic and creative life’. In Creative Connections*, our five-year development plan for the arts, 2007-2012, we identify four main themes covering what we believe needs to be done to achieve this vision - promoting the value of the arts; strengthening the arts; increasing audiences and improving our organisation’s performance. Cover Image: Cristina Catalina in ‘This Other City’ by Tinderbox Theatre Company. Theatre Tinderbox by City’ Other ‘This in Catalina Cristina Image: Cover Heaney Christopher Photo: In this Annual Review 2009-10, you will see the progress that has been made in these areas, from international profiling of the arts and expansion of arts-led regeneration projects, to strengthening connections with the business sector and Northern Ireland’s continuing participation in the 2012 Cultural Olympiad and Legacy Trust. * available at www.artscouncil-ni.org Maiden Voyage, ‘4 Quartets’. ‘4 Voyage, Maiden Photography Fox Joe Photo: arts council of northern ireland annual review 2009-10 arts council of northern ireland annual review 2009-10 Contents Welcome Welcome to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland’s A brief summary of our Accounts for the financial ‘Building for the Future’ - Chairman’s Foreword 6 Annual Review 2009-2010. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp.