Libraries and Archives of the Anarchist Movement in Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Chapter 1

Notes Introduction 1. Timothy Campbell, introduction to Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy by Roberto Esposito (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), vii. 2. David Graeber, “The Sadness of post- Workerism or Art and Immaterial Labor Conference a Sort of Review,” The Commoner, April 1, 2008, accessed May 22, 2011, http://www.commoner.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/graeber_ sadness.pdf. 3. Michel Foucault, Society Must Be Defended 1975–1976 (New York: Picador, 2003), 210, 211, 212. 4. Ibid., 213. 5. Racism works for the state as “a break into the domain of life that is under power’s control: the break between what must live and what must die” (ibid., 254). 6. Ibid., 212. 7. Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 219. 8. Ibid., 224. 9. Ibid., 229. 10. See Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998) and State of Exception (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005). 11. Esposito, Bios. Biopolitics and Philosophy, 14, 15. 12. Ibid., 147. 13. Laurent Dubreuil, “Leaving Politics. Bios, Zo¯e¯ Life,” Diacritics 36.2 (2006): 88. 14. Paolo Virno, A Grammar of the Multitude (New York: Semiotext[e], 2004), 81. Chapter 1 1. Catalogo Bolaffi delle Fiat, 1899–1970; repertorio completo della produzione automobilistica Fiat dalle origini ad oggi, ed. Angelo Tito Anselmi (Turin: G. Bolaffi , 1970), 15. 2. Gwyn A. Williams, introduction to The Occupation of the Factories: Italy 1920, by Paolo Spriano (London: Pluto Press, 1975), 9. See also Giorgio Porosini, 174 ● Notes Il capitalismo italiano nella prima guerra mondiale (Florence: La Nuova Italia Editore, 1975), 10–17, and Rosario Romero, Breve storia della grande industria in Italia 1861–1961 (Milan: Il Saggiatore, 1988), 89–97. -

Remembering Spain : Italian Anarchist Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War

Remembering Spain : Italian anarchist Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War Umberto Marzocchi 2005, Updated in 2014 Contents Umberto Marzocchi 3 Introduction 4 Italian Anarchist Volunteers in Spain 6 July 1936 ................................... 6 August 1936 ................................. 8 September 1936 ............................... 10 October 1936 ................................. 11 November 1936 ................................ 13 December 1936 ................................ 15 January, February, March 1937 ....................... 18 April 1937 ................................... 19 May 1937 ................................... 23 Epilogue: the death of Berneri ....................... 26 UMBERTO MARZOCCHI – Notes on his life 27 Note on the Text 30 2 Umberto Marzocchi He was born in Florence on 10 October 1900. A shipyard worker in La Spezia, he became an anarchist at a very early age and by 1917 was secretary of the metal- workers’ union affiliated to the USI (Italian Syndicalist Union), thanks to his youth which precluded his being mobilised for front-line service as a reprisal. During the “Red Biennium” he took part in the struggles alongside the renowned La Spezia anarchist, Pasquale Binazzi, the director of Il Libertario newspaper. In 1920 he was part of a gang of anarchists that attacked the La Spezia arsenal, overpowering the security guards and carrying off two machine guns and several rifles, in the,alas disappointed, hope of triggering a revolutionary uprising in the city. In 1921, vis- iting Rome to reach an agreement with Argo Secondari, he took over as organiser of the Arditi del Popolo (People’s Commandos) in the region; this organisation was to give good account of itself during the “Sarzana incidents”. Moving to Savona, he organised the meeting between Malatesta and the pro-Bolshevik Russian anar- chist Sandomirsky who arrived in Rapallo in the wake of the Chicherin delegation as its Press Officer. -

Centro Studi Sea

CENTRO STUDI SEA ISSN 2240-7596 AMMENTU Bollettino Storico, Archivistico e Consolare del Mediterraneo (ABSAC) N. 3 gennaio - dicembre 2013 www.centrostudisea.it/ammentu/ Direzione Martino CONTU (direttore), Giampaolo ATZEI, Manuela GARAU. Comitato di redazione Lucia CAPUZZI, Maria Grazia CUGUSI, Lorenzo DI BIASE, Maria Luisa GENTILESCHI, Antoni MARIMÓN RIUTORT, Francesca MAZZUZI, Roberta MURRONI, Carlo PILLAI, Domenico RIPA, Maria Elena SEU, Maria Angel SEGOVIA MARTI, Frank THEMA, Dante TURCATTI, Maria Eugenia VENERI, Antoni VIVES REUS, Franca ZANDA. Comitato scientifico Nunziatella ALESSANDRINI, Universidade Nova de Lisboa/Universidade dos Açores (Portogallo); Pasquale AMATO, Università di Messina - Università per stranieri ―Dante Alighieri‖ di Reggio Calabria (Italia); Juan Andrés BRESCIANI, Universidad de la República (Uruguay); Margarita CARRIQUIRY, Universidad Católica del Uruguay (Uruguay); Giuseppe DONEDDU, Università di Sassari (Italia); Luciano GALLINARI, Istituto di Storia dell‘Europa Mediterranea del CNR (Italia); Elda GONZÁLEZ MARTÍNEZ, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas (Spagna); Antoine-Marie GRAZIANI, Università di Corsica Pasquale Paoli - Institut Universitaire de France, Paris (Francia); Rosa Maria GRILLO, Università di Salerno (Italia); Victor MALLIA MILANES, University of Malta (Malta); Roberto MORESCO, Società Ligure di Storia Patria di Genova (Italia); Fabrizio PANZERA, Archivio di Stato di Bellinzona (Svizzera); Roberto PORRÀ, Soprintendenza Archivistica della Sardegna (Italia); Didier REY, Università di Corsica Pasquale Paoli (Francia), Sebastià SERRA BUSQUETS, Universidad de las Islas Baleares (Spagna); Cecilia TASCA, Università di Cagliari (Italia). Comitato di lettura La Direzione di AMMENTU sottopone a valutazione (referee), in forma anonima, tutti i contributi ricevuti per la pubblicazione. Responsabile del sito Stefano ORRÙ AMMENTU - Bollettino Storico, Archivistico e Consolare del Mediterraneo (ABSAC) Periodico annuale pubblicato dal Centro Studi SEA di Villacidro. -

Poésie D'un Rebelle

Poésie d’un rebelle. Isabelle Felici To cite this version: Isabelle Felici. Poésie d’un rebelle. : Gigi Damiani. Poète, anarchiste, émigré (1876-1953). Atlier de création libertaire, 2009, 978-2-35104-027-0 <http://www.atelierdecreationlibertaire.com/Poesie- d-un-rebelle.html>. <hal-01359814> HAL Id: hal-01359814 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01359814 Submitted on 8 Sep 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ETTE ÉTUDE EST CONSACRÉE à l’œuvre poétique de Gigi Damiani, I SABELLE ELICI C I F grand nom du journalisme anarchiste italien et compagnon I EL Cde route d’Errico Malatesta. Si le parcours de vie de cet F autodidacte commence et se termine à Rome (1876-1953), il le conduit dans de nombreuses métropoles, notamment celles où s’est Poésie SABELLE installée une forte communauté italienne : São Paulo, Marseille, I Paris, Bruxelles, Tunis. Partout il compose des poésies de lutte et d’espoir, surtout dans les moments les plus troubles de l’histoire d’un rebelle italienne et internationale, dont des pans entiers apparaissent ainsi Poète, anarchiste, émigré (1876-1953) sous un angle inédit, tandis que se dessine également le parcours d’un militant qui, quels qu’aient été les sacrifices à accomplir, n’a jamais suivi d’autres chemins que les chemins de la liberté. -

The Winding Paths of Capital

giovanni arrighi THE WINDING PATHS OF CAPITAL Interview by David Harvey Could you tell us about your family background and your education? was born in Milan in 1937. On my mother’s side, my fam- ily background was bourgeois. My grandfather, the son of Swiss immigrants to Italy, had risen from the ranks of the labour aristocracy to establish his own factories in the early twentieth Icentury, manufacturing textile machinery and later, heating and air- conditioning equipment. My father was the son of a railway worker, born in Tuscany. He came to Milan and got a job in my maternal grand- father’s factory—in other words, he ended up marrying the boss’s daughter. There were tensions, which eventually resulted in my father setting up his own business, in competition with his father-in-law. Both shared anti-fascist sentiments, however, and that greatly influenced my early childhood, dominated as it was by the war: the Nazi occupation of Northern Italy after Rome’s surrender in 1943, the Resistance and the arrival of the Allied troops. My father died suddenly in a car accident, when I was 18. I decided to keep his company going, against my grandfather’s advice, and entered the Università Bocconi to study economics, hoping it would help me understand how to run the firm. The Economics Department was a neo- classical stronghold, untouched by Keynesianism of any kind, and no help at all with my father’s business. I finally realized I would have to close it down. I then spent two years on the shop-floor of one of my new left review 56 mar apr 2009 61 62 nlr 56 grandfather’s firms, collecting data on the organization of the production process. -

SL/945.08/MIL C a 1898 : Dal Processo a Carrara Alle Cannonate

SL/945.08/MIL C A 1898 : dal processo a Carrara alle cannonate di Milano / a cura di Beniamino Gemignani. - Massa : Società Editrice Apuana, 1998. - 1 v. ; 33 cm. CDD: 945.08 1. Carrara - 1898 2. Processi Politici - Carrara - 1898 3. Eco del Carrione 29 luglio 1900 : un fatto. - Carrara : G.A.R., stampa 1981 (Carrara : La Cooperativa Tipolitografica). - 46 p. ; 24 cm. CDD: 320.57 1. Anarchismo - Bresci Gaetano 29 luglio 1900 : un fatto / G.A.R. Carrara. - Carrara : edito a cura dei Gruppi Anarchici Riuniti, stampa 1981 (Carrara : La Cooperativa Tipolitografica). - 44 p. : ill. ; 24 625 : libro bianco sulla legge Reale / a cura del Centro di iniziativa Luca Rossi. - Locate Triulzi (MI) : Cento Fiori, stampa 1990. - 437 p. : ill. ; 24 cm. Saggi e interventi di : Ernesto Balducci, Lelio Basso, Cesare Bermani, Sandro Bernasconi, Comitato Pedro, Massimo Croci, Franco Fortini, Umberto Gay, Tiziana Maiolo, Amedeo Santosuosso, Giuliano Spazzali, Angela Valcavi, Gilberto Vitale, Agostino Viviani 75 aniversari fundacional de la CNT : la historia obrera en acciò : exposiciò grafica-documental. - Barcellona : Ajuntament de Barcelona, 1985. - 39 p. : ill. ; 20 cm. Presentazione di Maria Aurelia Capmany CDD: 335.82 1. Anarchismo 75° aniversario de la C.N.T. (Adherida a la A.I.T.) : 1910 1985 : prefigurando futuro. - [S. l.] : C.N.T., 1985 (Madrid : Artes Graficas Minerva, S. A.). - 31 p. : ill. ; 15 cm. A bocca chiusa : cronaca e documenti del processo contro i "dissidenti di sinistra" in Jugoslavia (Belgrado 1984-85) / a cura del Centro Studi Libertari di Trieste e del Centro Studi garanzie costituzionali Garcos di Milano. - Carrara : La Cooperativa Tipolitografica Editrice, 1986. -

Post/Autonomia

Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy Andrea Hajek, PhD Visiting Fellow at the Centre for the Study of Cultural Memory IGRS, University of London Abstract More than 30 years ago the violent death - on 11 March 1977 - of a left-wing student in the Italian city of Bologna brought an end to a student protest movement, the ‘Movement of ’77’. Today nostalgia dominates public commemorations of the movement as it manifested itself in Bologna. However, this memory is not an exclusive memory of the 1977 generation. A number of young, left-wing activists that draw on the myth of 1977 in Bologna and in particular on the memory of the local Workers Autonomy faction appropriate this memory in a similarly nostalgic manner. This article then explores the value of nostalgia in generational memory: how does it relate to past, present and future, and to what extent does it influence processes of identity formation among youth groups? I argue that nostalgia is more than a longing for the past, and that it can be conceived as progressive and future-orientated, providing empowerment for specific social groups. Keywords Nostalgia, generational memory, 1970s, Italian student movements, Workers Autonomy. Word count: ca. 6.000 (incl. notes and references) 1 Progressive nostalgia. Appropriating memories of protest and contention in contemporary Italy ‘Pagherete caro, pagherete tutto!’1 On 12 March 2011, this slogan reverberated in the streets of the Italian city of Bologna, 34 years after left-wing student Francesco Lorusso was shot dead by police during student protests. Lorusso’s disputed and unresolved death on 11 March 1977 - for which the police officer who shot him was never tried - as well as the violent incidents that subsequently kept Bologna in a state of high tension, have left a deep wound in the city, in particular among Lorusso’s former companions and friends. -

Works Cited – Films

Works cited – films Ali (Michael Mann, 2001) All the President’s Men (Alan J Pakula, 1976) American Beauty (Sam Mendes, 1998) American History X (Tony Kaye, 1998) American Psycho (Mary Harron, 2000) American Splendor (Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, 2003) Arlington Road (Mark Pellington, 1999) Being There (Hal Ashby, 1980) Billy Elliott (Stephen Daldry, 2000) Black Christmas (Bob Clark, 1975) Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981) Bob Roberts (Tim Robbins, 1992) Bowling for Columbine (Michael Moore, 2002) Brassed Off (Mark Herman, 1996) The Brood (David Cronenberg, 1979) Bulworth (Warren Beatty, 1998) Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003) Control Room (Jehane Noujaim, 2004) The China Syndrome (James Bridges, 1979) Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974) Clerks (Kevin Smith, 1994) Conspiracy Theory (Richard Donner, 1997) The Conversation (Francis Ford Coppola, 1974) The Corporation (Jennifer Abbott and Mark Achbar, 2004) Crumb (Terry Zwigoff, 1994) Dave (Ivan Reitman, 1993) The Defector (Raoul Lévy, 1965) La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960) Dr Strangelove, or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964) Evil Dead II (Sam Raimi, 1987) 201 Executive Action (David Miller, 1973) eXistenZ (David Cronenberg, 1999) The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973) Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004) Falling Down (Joel Schumacher, 1993) Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2002) Fight Club (David Fincher, 1999) The Firm (Sydney Pollack, 1993) The Fly (David Cronenberg, 1986) The Forgotten (Joseph Ruben, 2004) Friday the 13th -

Marie Louise Berneri a Tribute

The Anarchist Library Anti-Copyright Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute Phillip Sansom Phillip Sansom Marie Louise Berneri A Tribute June, 1977 Zero Number 1, June, 1977, page 9 Scanned from original. theanarchistlibrary.org June, 1977 Workers in Stalin’s Russia. M.L. Berneri. Freedom Press, 1944. “Sexuality and Freedom.” M.L. Berneri. Now no. 5. Published by George Woodcock. Journey Through Utopia. M.L. Berneri. Routledge Kegan Paul. 1950. Contents Marie Louise Berneri, A tribute, Freedom Press 1949. Neither East nor West, Selected Writings of Marie Louise Berneri. Edited by Vernon Richards. Freedom Press, 1952 References 13 14 3 References 13 And she finishes in her own words with: “The importance Note: Zero (Anarchist/Anarca-feminist Newsmagazine) was of Dr. Reich’s theories is enormous. To those who do not seek published in London in the late 1970s. intellectual exercise, but means of saving mankind from the “We cannot build until the working class gets rid of its illu- destruction it seems to be approaching, this book will be an sions, its acceptance of bosses and faith in leaders. Our pol- individual source of help and encouragement. To anarchists the icy consists in educating it, in stimulating its class instinct fundamental belief in human nature, in complete freedom from and teaching methods of struggle…It is a hard and long task, the authority of the family, the Church and the State will be but…our way of refusing to attempt the futile task of patching familiar, but the scientific arguments put forward to back this up a rotten world, but of striving to build a new one, is notonly belief will form an indispensible addition to their theoretical constructive but is also the only way out.” knowledge.” Space restricts detailed mention of all those who, as she – Marie Louise Berneri, December, 1940 would have been the first to admit, Influenced her develop- ment. -

Transnational Anarchism Against Fascisms: Subaltern Geopolitics and Spaces of Exile in Camillo Berneri’S Work Federico Ferretti

Transnational Anarchism Against Fascisms: subaltern geopolitics and spaces of exile in Camillo Berneri’s work Federico Ferretti To cite this version: Federico Ferretti. Transnational Anarchism Against Fascisms: subaltern geopolitics and spaces of exile in Camillo Berneri’s work. eds. D. Featherstone, N. Copsey and K. Brasken. Anti-Fascism in a Global Perspective, Routledge, pp.176-196, 2020, 10.4324/9780429058356-9. hal-03030097 HAL Id: hal-03030097 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03030097 Submitted on 29 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Transnational anarchism against fascisms: Subaltern geopolitics and spaces of exile in Camillo Berneri’s work Federico Ferretti UCD School of Geography [email protected] This paper addresses the life and works of transnational anarchist and antifascist Camillo Berneri (1897–1937) drawing upon Berneri’s writings, never translated into English with few exceptions, and on the abundant documentation available in his archives, especially the Archivio Berneri-Chessa in Reggio Emilia (mostly published in Italy now). Berneri is an author relatively well-known in Italian scholarship, and these archives were explored by many Italian historians: in this paper, I extend this literature by discussing for the first time Berneri’s works and trajectories through spatial lenses, together with their possible contributions to international scholarship in the fields of critical, radical and subaltern geopolitics. -

Witness for the Prosecution

Witness for the Prosecution Colin Ward 1974 The revival of interest in anarchism at the time of the Spanish Revolution in 1936 ledtothe publication of Spain and the World, a fortnightly Freedom Press journal which changed to Revolt! in the months between the end of the war in Spain and the beginning of the Second World War. Then War Commentary was started, its name reverting to the traditional Freedom inAugust 1945. As one of the very few journals which were totally opposed to the war aims of both sides, War Commentary was an obvious candidate for the attentions of the Special Branch, but it was not until the last year of the war that serious persecution began. In November 1944 John Olday, the paper’s cartoonist, was arrested and after a protracted trial was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment for ‘stealing by finding an identity card’. Two months earlier T. W. Brown of Kingston had been jailed for 15 months for distributing ‘seditious’ leaflets. The prosecution at the Old Bailey had drawn the attention of the court to the fact that thepenalty could have been 14 years. On 12 December 1944, officers of the Special Branch raided the Freedom Press office andthe homes of four of the editors and sympathisers. Search warrants had been issued under Defence Regulation 39b, which declared that no person should seduce members of the armed forces from their duty, and Regulation 88a which enabled articles to be seized if they were evidence of the commission of such an offence. At the end of December, Special Branch officers, led byDetec- tive Inspector Whitehead, searched the belongings of soldiers in various parts of the country. -

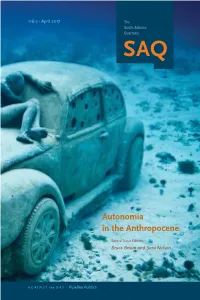

Autonomia in the Anthropocene

SAQ 116:2 • April 2017 The South Atlantic Autonomia in the Anthropocene Quarterly Bruce Braun and Sara Nelson, Special Issue Editors Autonomia in the Anthropocene: SAQ New Challenges to Radical Politics Sara Nelson and Bruce Braun Species, Nature, and the Politics of the Common: 116:2 From Virno to Simondon Miriam Tola • April Anthropocene and Anthropogenesis: Philosophical Anthropology 2017 and the Ends of Man Jason Read At the Limits of Species Being: Anthropocene Autonomia and the Sensing the Anthropocene Elizabeth R. Johnson The Ends of Humans: Anthropocene, Autonomism, Antagonism, and the Illusions of our Epoch Elizabeth A. Povinelli The Automaton of the Anthropocene: On Carbosilicon Machines and Cyberfossil Capital Matteo Pasquinelli Intermittent Grids Karen Pinkus Autonomia Anthropocene: Cover: Anthropocene, Victims, Narrators, and Revolutionaries underwater sculpture, Marco Armiero and Massimo De Angelis depth 8m, MUSA Collection, in the Anthropocene Cancun/Isla Mujeres, Mexico. Special Issue Editors Refusing the World: © Jason deCaires Taylor. Silence, Commoning, All rights reserved, Bruce Braun and Sara Nelson and the Anthropocene DACS / ARS 2017 Anja Kanngieser and Nicholas Beuret Autonomy and the Intrusion of Gaia Duke Isabelle Stengers AGAINST the DAY • Pipeline Politics Editor Michael Hardt Editorial Board Srinivas Aravamudan Rey Chow Roberto M. Dainotto Fredric Jameson Ranjana Khanna The South Atlantic Wahneema Lubiano Quarterly was founded in 1901 by Walter D. Mignolo John Spencer Bassett. Kenneth Surin Kathi Weeks Robyn