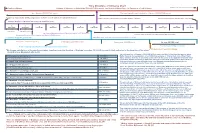

Sanskrit Prosody,/And Numerical Symbols Explained

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meter of Classical Arabic Poetry

Pegs, Cords, and Ghuls: Meter of Classical Arabic Poetry Hazel Scott Haverford College Department of Linguistics, Swarthmore College Fall 2009 There are many reasons to read poetry, filled with heroics and folly, sweeping metaphors and engaging rhymes. It can reveal much about a shared cultural history and the depths of the human soul; for linguists, it also provides insights into the nature of language itself. As a particular subset of a language, poetry is one case study for understanding the use of a language and the underlying rules that govern it. This paper explores the metrical system of classical Arabic poetry and its theoretical representations. The prevailing classification is from the 8th century C.E., based on the work of the scholar al-Khaliil, and I evaluate modern attempts to situate the meters within a more universal theory. I analyze the meter of two early Arabic poems, and observe the descriptive accuracy of al-Khaliil’s system, and then provide an analysis of the major alternative accounts. By incorporating linguistic concepts such as binarity and prosodic constraints, the newer models improve on the general accessibility of their theories with greater explanatory potential. The use of this analysis to identify and account for the four most commonly used meters, for example, highlights the significance of these models over al-Khaliil’s basic enumerations. The study is situated within a discussion of cultural history and the modern application of these meters, and a reflection on the oral nature of these poems. The opportunities created for easier cross-linguistic comparisons are crucial for a broader understanding of poetry, enhanced by Arabic’s complex levels of metrical patterns, and with conclusions that can inform wider linguistic study.* Introduction Classical Arabic poetry is traditionally characterized by its use of one of the sixteen * I would like to thank my advisor, Professor K. -

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda

[VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 3 I JULY – SEPT 2018] e ISSN 2348 –1269, Print ISSN 2349-5138 http://ijrar.com/ Cosmos Impact Factor 4.236 An Introduction to Sanskrit Chanda MITHUN HOWLADAR Ph. D Scholar, Department of Sanskrit, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia, West Bengal Received: May 22, 2018 Accepted: July 11, 2018 ABSTRACT We can generally say, any composition which has a musical sound, is called chanda. Chanda has been one of the Vedāṅgas since Vedic period. Vedic verses are composed in several chandas. The number of Vedic chandas is 21, out of which 7 are mainly used. Earliest poetic composition in public language (laukika Sanskrit) started from Valmiki, later it became a fashion and then a discipline for composition (kāvya). But here has been a difference in Vedic and laukika chandas. Where Vedic chnadas are identified by the number of syllables (varṇa or akṣara) in a line of verse or whole verse and the number of lines in the verse, laukika chanda is identified by the order of the laghu-guru syllables. The number of the laukika chandas is not yet finally defined but many texts have been composed describing the different number of chandas. Each chanda of laukika Sanskrit (post Vedic Sanskrit) consists of four pādas or caraṇas, that is, the fourth part of the chanda. Keywords: Chanda, Vedāṅgas, Chandaśāstra, pāda, Chandomañjarī. Introduction: Veda, the oldest literature in the world, is also called Chandas because the Vedic mantras (compositions) are all metric compositions (Chandobaddha). All the four Saṁhitās (with some exceptions in Yajurveda and Atharvaveda) are of this nature. -

Contribution of Leelavathi to Prosody

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 20, Issue 8, Ver. VI (Aug. 2015), PP 08-13 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Contribution of Leelavathi to Prosody Dr.K.K.Geethakumary Associate Professor, Dept.of Sanskrit, University of Calicut, India, Kerala, 673635) I. Introduction Leelavathi, a treatise on Mathematics, is written by Bhaskara II who lived in 12th century A.D. Besides explaining the details of mathematical concepts that were in existence up to that period, the text introduces some new mathematical concepts. This paper is an attempt to analyze the metres employed in Leelavathi as well as the concepts of permutation and combination introduced by the author in the same text. Key words:-Combination, Leelavathi, Meruprasthara, Metre, Permutation, II. Metres In The Text Leelavathi In poetry, metre has a significant role to contribute the emotive aspect. The spontaneous out pore of emotion always happens through a suitable metre that is revealed in the mind of the poet at the time of literary creation. Rhythm itself is the life of the metre as it transfuses the emotion. Varied compositions of diversified rhythms which are innumerable give birth to different metres in poetry. Early poeticians like Bhamaha, Dandin, Vamana, Rudrada and Rajasekhara have stated that erudition in prosody is essential for making poetical composition. In Vedic period, the skill of Vedic Rishis in handling the language and metre for expressing their ideas is also equally attractive. The metres used are well suited to the types of poetry, the ideas expressed in them and the content exposed. -

The Rhythm of the Gods' Voice. the Suggestion of Divine Presence

T he Rhythm of the Gods’ Voice. The Suggestion of Divine Presence through Prosody* E l ritmo de la voz de los dioses. La sugerencia de la presencia divina a través de la prosodia Ronald Blankenborg Radboud University Nijmegen [email protected] Abstract Resumen I n this article, I draw attention to the E ste estudio se centra en la meticulosidad gods’ pickiness in the audible flow of de los dioses en el flujo audible de sus expre- their utterances, a prosodic characteris- siones, una característica prosódica del habla tic of speech that evokes the presence of que evoca la presencia divina. La poesía hexa- the divine. Hexametric poetry itself is the métrica es en sí misma el lenguaje de la per- * I want to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of ARYS for their suggestions and com- ments. https://doi.org/10.20318/arys.2020.5310 - Arys, 18, 2020 [123-154] issn 1575-166x 124 Ronald Blankenborg language of permanency, as evidenced by manencia, como pone de manifiesto la litera- wisdom literature, funereal and dedicatory tura sapiencial y las inscripciones funerarias inscriptions: epic poetry is the embedded y dedicatorias: la poesía épica es el lenguaje direct speech of a goddess. Outside hex- directo integrado de una diosa. Más allá de ametric poetry, the gods’ special speech la poesía hexamétrica, el habla especial de los is primarily expressed through prosodic dioses es principalmente expresado mediante means, notably through a shift in rhythmic recursos prosódicos, especialmente a través profile. Such a shift deliberately captures, de un cambio en el perfil rítmico. -

Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India

Journal of Interdisciplinary Cycle Research ISSN NO: 0022-1945 Development of Indian Classical Language and Literature on Modern Creative Writing of India Ceazer Gonsalves Assistant Professor Department of English Milagres College, Udupi, Karnataka Email: [email protected] Abstract Language is a medium through which we express our thought. While the literature is a mirror which reflects ideas and philosophies which govern our society, hence to know any particular culture and its traditions it is very important we understand the evolution of its language and the various forms of literature like poetry, plan drama, religious and non religious writing. Indian language play a very important role in our culture and one of the earliest language is Sanskrit ever since human being have invented scripts, writing has reflected the culture, life style, society and the polity of the contemporary society. Each culture evolved its own language and creates a number of literary bases and this literary base of civilization tells us about the evolution of its language and culture through the span of centuries. As we know Sanskrit language is a mother of most of the Indian language .The Vedas and Puranas, Mahabharata, Ramayana all these works were written in Sanskrit language and also variety of secular and regional literature created in the past so that we can understand better. It is among the 22 language listed in the Indian Constitution .Sanskrit gave importance to study linguist scientifically during 18th and 19th century. Sanskrit is the only language that transcended the barriers of regions and boundaries from the north to the south and east to the west .There is no part of India that has not contributed to all being affected by language. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

The Poetry Handbook I Read / That John Donne Must Be Taken at Speed : / Which Is All Very Well / Were It Not for the Smell / of His Feet Catechising His Creed.)

Introduction his book is for anyone who wants to read poetry with a better understanding of its craft and technique ; it is also a textbook T and crib for school and undergraduate students facing exams in practical criticism. Teaching the practical criticism of poetry at several universities, and talking to students about their previous teaching, has made me sharply aware of how little consensus there is about the subject. Some teachers do not distinguish practical critic- ism from critical theory, or regard it as a critical theory, to be taught alongside psychoanalytical, feminist, Marxist, and structuralist theor- ies ; others seem to do very little except invite discussion of ‘how it feels’ to read poem x. And as practical criticism (though not always called that) remains compulsory in most English Literature course- work and exams, at school and university, this is an unwelcome state of affairs. For students there are many consequences. Teachers at school and university may contradict one another, and too rarely put the problem of differing viewpoints and frameworks for analysis in perspective ; important aspects of the subject are omitted in the confusion, leaving otherwise more than competent students with little or no idea of what they are being asked to do. How can this be remedied without losing the richness and diversity of thought which, at its best, practical criticism can foster ? What are the basics ? How may they best be taught ? My own answer is that the basics are an understanding of and ability to judge the elements of a poet’s craft. Profoundly different as they are, Chaucer, Shakespeare, Pope, Dickinson, Eliot, Walcott, and Plath could readily converse about the techniques of which they are common masters ; few undergraduates I have encountered know much about metre beyond the terms ‘blank verse’ and ‘iambic pentameter’, much about form beyond ‘couplet’ and ‘sonnet’, or anything about rhyme more complicated than an assertion that two words do or don’t. -

Time Structure of Universe Chart

Time Structure of Universe Chart Creation of Universe Lifespan of Universe - 1 Maha Kalpa (311.040 Trillion years, One Breath of Maha-Visnu - An Expansion of Lord Krishna) Complete destruction of Universe Age of Universe: 155.52197 Trillion years Time remaining until complete destruction of Universe: 155.51803 Trillion years At beginning of Brahma's day, all living beings become manifest from the unmanifest state (Bhagavad-Gita 8.18) 1st day of Brahma in his 51st year (current time position of Brahma) When night falls, all living beings become unmanifest 1 Kalpa (Daytime of Brahma, 12 hours)=4.32 Billion years 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas Chaturyugas 1 Manvantara 306.72 Million years Age of current Manvantara and current Manu (Vaivasvata): 120.533 Million years Time remaining for current day of Brahma: 2.347051 Billion years Between each Manvantara there is a juncture (sandhya) of 1.728 Million years 1 Chaturyuga (4 yugas)=4.32 Million years 28th Chaturyuga of the 7th manvantara (current time position) Satya-yuga (1.728 million years) Treta-yuga (1.296 million years) Dvapara-yuga (864,000 years) Kali-yuga (432,000 years) Time remaining for Kali-yuga: 427,000 years At end of each yuga and at the start of a new yuga, there is a juncture period 5000 years (current time position in Kali-yuga) "By human calculation, a thousand ages taken together form the duration of Brahma's one day [4.32 billion years]. -

The Medea of Euripides and Seneca: a Comparison

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1941 The Medea of Euripides and Seneca: A Comparison Mary Enrico Frisch Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Frisch, Mary Enrico, "The Medea of Euripides and Seneca: A Comparison" (1941). Master's Theses. 180. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/180 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1941 Mary Enrico Frisch -If.. THE MEDEA OF EURIPIDES AND SENECA: A COMPARISON by Sister Mary Enrico Frisch, S.S.N.D. A Thesis submitted 1n partial ~ul~illment o~ the requirements ~or the degree o~ Master o~ Arts Loyola University August, 1941 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I Introduction: Survey o~ Opinion. 1 II Broad Similarities in Moti~ and 6 Sentiment. III Broad Similarities in the Plot 30 o~ the Medea o~ Euripides and the Medea o~ Seneca. IV Parallels in Phraseology. 51 v Characters and Their Attitude 73 to the Gods. Bibliography a. Re~erences ~or the Medea 91 o~ Euripides. b. Re~erences ~or the Medea 95 o~ Seneca. c. General Works. 98 THE MEDEA OF EURIPIDES AND SENECA: A COMPARISON Chapter I INTRODUCTION: SURVEY OF OPINION It is not a new theory that Seneca used the plays o~ Eurip ides as models for his Latin tragedies, particularly his Medea, Hippolytus, Hercules Furens, Troades and the Phoenissae. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

![History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7681/history-of-indian-philosophy-upani%C3%B1ads-key-terms-questions-pin-d%C5%93-%C3%A4%C3%BCn-aatmn-xmr-s-sar-kmr-mae-aannd-847681.webp)

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions %Pin;Dœ Äün! Aatmn! Xmr S<Sar Kmr Mae] Aannd

History of Indian Philosophy Upaniñads: Key Terms & Questions KEY TERMS %pin;dœ *to sit down near to, to approach *the sitting down at the feet of another to listen to his words, hence, secret knowledge upaniñad *the mystery which underlies or rests underneath the external system of things Upanishad *esoteric doctrine, secret doctrine, words of mystery *a class of philosophical writings *lit. growth, expansion, evolution, swelling of the spirit or soul äün! *the sacred word, the Veda, a sacred text or Mantra (in Vedas) *the sacred syllable OM brahman *religious or spiritual knowledge brahman *the One, self-existent impersonal Spirit, universal Soul, Divine Essence and source from which all created things emanate or with which they are identified and to which they return, the Absolute, the Eternal AaTmn! *variously derived from: to breathe, to move, to blow, the breath ätman *the soul, principle of life and sensation atman *the highest personal principle of life xmR *that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, law dharma *right, justice dharma *virtue, morality, religion, religious merit, good works s<sar *going or wandering through, undergoing trasmigration *a course, passage, passing through a succession of states, circuit of mundane saàsära existence, the world, secular life, worldly illusion samsara kmR from kri, to act; thus action, performance *making, doing, performing karma (the law governing the fruit of action) karma mae] *emancipation, liberation, release mokña *release from worldly existence or transmigration, final