ATHOLL HOUSE PRODUCTIONS LIMITED Respondent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Service Review

Delivering Quality First in Scotland DELIVERING QUALITY FIRST IN SCOTLAND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The BBC is the most trusted broadcaster in Scotland and a core part of the life of the nation. It unites the audience in enjoyment of the most popular TV, radio and online services, while also championing the diversity of the interests, cultures and languages of this nation of islands and regions. It is valued for upholding the highest standards of quality. The BBC’s commitment to Scotland is to offer a range and depth of programming which is both widely relevant and uniquely distinctive. As the only broadcaster which has invested in covering the whole country across all platforms, it is well-placed to do this. The BBC’s ambition in Scotland is to serve as a national forum, connecting the people of Scotland to each other, to the wider UK and to the rest of the world. As a public service broadcaster which has secure funding and global reach, the BBC is well-placed to achieve this. The BBC provides value to audiences in Scotland in two main ways: through programmes and services which are made in and for Scotland specifically; and through programmes and services which are broadcast across the whole UK. In Scotland, the audience rates the BBC as the leading provider of both Scottish news and non-news programming. Reporting Scotland has the highest reach of any news bulletin; TV opt-out programming1 reaches 44% of the audience every week and is highly appreciated; BBC Radio Scotland is second in popularity only to BBC Radio Two; BBC Scotland’s online portfolio has 3.7m weekly UK unique browsers2; and BBC ALBA attracts half a million English-speaking viewers to its Gaelic TV channel every week. -

SCCJR Reports 2007-2016

The Scottish Centre for Crime and Justice Research: Celebrating 10 Years CONTENTS 10 YEARS OF SCCJR .................................................................. 4 Communicating and Engaging .................................................................................................................................................... 34 Welcome to the 10-Year Anniversary Report of the Scottish Centre Knowledge Exchange ................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 34 for Crime and Justice Research (SCCJR) ...................................................................................................................................... 4 From Vision to Reality – Transforming Scotland’s Care of Women in Custody ........................................................................................ 34 Domestic abuse in the Scottish Context – What Works to Reduce Incidence and Harm ................................................................ 34 The Next 10 Years of SCCJR ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Constructing ‘Problematic’ Identities ................................................................................................................................................................................ 34 Who we are ................................................................................................................................................................................................ -

Scotland Management Review 2009/10

SCOTLAND MANAGEMENT REVIEW 2009/10 A INTRODUCTION FROM NATIONAL DIRECTOR A DIFFICULT AND CHALLENGING YEAR HAS, HOWEVER, ALSO BEEN ONE OF TREMENDOUS ACHIEVEMENT, CHARACTERISED BY LANDMARK PROGRAMMES AND INCREASED BBC INVESTMENT IN BROADCASTING IN SCOTLAND. Audiences are at the heart of all of our broadcasting and, across 2009/2010, we looked to ensure that the many diverse needs and tastes of our viewers and listeners were met, on television, radio and online. Across the month of September the This is Scotland season on BBC Four showcased the best of our nation’s culture, arts and music before a UK audience and the second part of Scotland’s History broadcast to critical acclaim at the turn of the year, on BBC One Scotland, network and on the BBC HD channel. Our news teams continued to bring the best local, national and international journalism to radio, television and online audiences across Scotland, from local reporting on the winter weather chaos “AGAINST A DIFFICULT FINANCIAL BACKDROP, BBC to coverage of the release of the Lockerbie bomber, which brought with it a prestigious Royal NETWORK BUSINESS IN SCOTLAND HAS CONTINUED Television Society award. The BBC’s Network Supply Review saw several key programmes transfer to Scotland during the TO INCREASE, AND WE ARE NOW STARTING TO course of the year. The Review Show and The Weakest Link both began filming in our studios atP acific REALISE THE FULL POTENTIAL OF OUR DIGITAL Quay in Glasgow. They joined a slate of new productions, across genres, which have helped boost BBC network investment in Scotland to over 6% of the total BBC spend, meeting the 2012 target TELEVISION AND RADIO STUDIOS AT PACIFIC QUAY set for us in 2007 by the Director-General and the BBC Trust. -

A History: 1993–2018

r e d l E m a d A @ : t i d e r C Scottish Grocers Federation 222/224 Queensferry Road A History: Edinburgh EH4 2BN 199 3– 2018 T: 0131 343 3300 E: [email protected] W: scottishshop.org.uk By Lawrie Dewar MBE Edited by Karen Peattie Foreword by Pete Cheema 1981 Tom Hood President 1962-1963 1981 Jack Suttie President 1966-1967 1981 David Woodside President 1969-1970 1981 Archie Alexander Federation Secretary 1982 Roy McFarlane President 1963-1964 1982 Malcolm MacLeod President 1967-1968 1982 John Aitken President 1968-1969 1982 Bruce Aitkenhead President 1973-1974 1982 Roger Rogerson President 1974-1975 1982 Stan Clarke President 1978-1979 Our industry is worth Honorary 1983 May Christie SGF NEX £5.2 billion per annum Members of the 1983 Ian Adam President 1956-1957 “ 1983 James McGuire President 1972-1973 1983 James Renwick President 1977-1978 to the Scottish economy Scottish Grocers’ 1984 John Irving President 1976-1977 1984 Willie McPhail and directly employs Federation 1984 BenSavage 1984 Geoff Walker over 41,000 people 1986 Madge Alexander 1987 Sam Kilburn ” 1987 Archie McNicol McCurrach’s 1989 Michæl Kempton Federation Accountant 1993 Lionel Cashin Mars UK 1996 Andrew Nicol President 1987-1988 1996 Walter McCubbin SGF NEX 1997 John Paterson SGF NEX 1998 Sarah Jeffrey MD, PGMA 1999 Calum Duncan SGF NEX 1999 Lambert Munro SGF NEX 2001 Lawrie Dewar President 1975-1976/Fed Sec 2001 Ross Kerr Walkers Crisps 2006 Eddie Thompson President 1998-2000 2006 Scott Landsburgh President 1994-1996/Fed Sec 2008 Dougie Edgar President 2000-2002 2012 Jim Botterill President 2002-2004 2012 David Sands President 1996-1998 2017 Tom Wilson President, 1980/81 and 1986/87 2017 Ian McDonald JW Filshill 2017 Alan McCaffer PepsiCo 2017 Bep Dhaliwal Mars Chocolate 2017 Sandy Wilkie Retired Milkman Foreword It is remarkable to think that the Scottish Technology, meanwhile, has been our Grocers’ Federation has reached such a friend and allows retailers to work in pivotal moment in its history. -

UNIVERSITY of STIRLING Mbnica Terribas I Sala Thesis Entitled

L UNIVERSITY OF STIRLING Mbnica Terribas i Sala Thesis entitled: TELEVISION, NATIONAL IDENTITY AND THE PUBLIC SPHERE Scottish -A comparative study of and Catalan discussion programmes - Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 1994 Oh, que cansatestic de la meva covarda,bruta, tan salvatgeterra i com magrada?ia d'allunyar-men nord enlla.... Perb no he de seguir mai el meu somni, i ein quedargaquffins a la mort. Salvador Espriu (1913-1985) A la meva fanulia, per vetllar l'esquitx. To Mark, the Bremen musiciansand el Llampec, for their patience. Acknowledgments This study would have never been possible without the co-operation and support of a greatmany peopleboth in the Catalanand the Scottishtelevision industries. To the teams of both Scottish Women and La Vida en un Xip, I owe special gratitude for the time spent and the information given. I hope that if this study helps to improve the understanding of the national identity question in Scotland and Catalonia and also increasethe democracy of our mass media, all those to which I have troubled may feel compensated. I would particularly like to thank the British Council and Caixa d'Estalvis i Pensionsde Barcelonafor the funding of this thesis and their human support during my two years in Scotland. This study owes its inspiration to Joaquim M. Puyal i Ortiga, whose ideas and efforts television democratic to encouragedt5 me to explore as a medium which everyoneshould have access. However, this thesis would have never beenfinished without the patience, guidancez: I and encouragementZ) of my principal supervisor,Philip Schlesinger,Cý who always believed in it. -

STV Statement 2014 FINAL

STV Statement 2014 Overall Strategy / Major Themes for the Year 2014: The Time is Now 2014 is a unique and exciting time for Scotland and STV is committed to playing a key role as a public service broadcaster by bringing viewers all the news, analysis and opinion in the lead up to the Scottish independence referendum, as well as the story of the Commonwealth Games and other crucial events throughout the year. STV is committed to providing quality and compelling public service broadcast content and we will continue to deliver in excess of licence requirements in 2014 and beyond. Scotland has a strong appetite for local news and we will continue to bring viewers a sustainable news service that clearly delivers what viewers want, not only on air but across multiple platforms via three distinct evening programmes serving Scotland’s regions, with an additional bulletin for Tayside, and regional Scottish news for ITV’s Daybreak . From April, we will deliver four bulletins as part of ITV’s flagship morning programme, Good Morning Britain . As we approach the referendum on Scottish independence on 18 September, STV will continue to provide a platform for debate around the key issues, bringing viewers all the news, analysis, discussion and opinions from both sides of the debate. We also plan to undertake our most ambitious and large scale results coverage to date with an overnight results programme on 18/19 September providing viewers with comprehensive coverage and analysis of the results that will determine Scotland's constitutional future. Digital business growth The diversification of STV’s digital business will continue in 2014 as we seek new platforms to deliver our quality content to audiences however and wherever they choose to consume it. -

Multiplatform Production June 2019 Multiplatform Production (MPP) Is BBC Scotland’S In-House Production Team

Multiplatform Production June 2019 Multiplatform Production (MPP) is BBC Scotland’s in-house production team. We make content for BBC Scotland TV, Radio and Digital platforms; BBC ALBA and BBC Radio nan Gàidheal as well as music, drama and speech programmes for network Radio and The Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo for BBC One. Our team works across Music, Entertainment and Events; Sport; Speech and Topical; Digital; Gaelic productions and includes the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra. 22 Graham Development for speech & Russell topical, Gaelic, sport, SSO, Head of music, entertainment, events, Development digital & innovation John J MacIsaac Gaelic - TV, radio, digital Editor, Gaelic Heather Kane Editor, Speech Speech & Topical & Topical Tom Connor Sport - TV, radio, digital Editor, Sport Pauline Law Head of Multiplatform Production Dominic Parker SSO Director, SSO David Staite Editor, Music, Music, Entertainment Entertainment and Events & Events Anthony Browne Digital Editor, Digital Morven MacKenzie Head of Business 3 Strand Title Description Contact Base Speech & Topical 4 Strand Title Description Contact Base Out for the Inspiration for our listeners with Emily Esson & Aberdeen Weekend (Radio weekend events and activities in Elizbeth Clark Scotland) Scotland. Out of Doors Discover the latest outdoor Fiona Aitken Aberdeen (Radio Scotland) activities and rural issues across Scotland with presenters Mark Stephen and Euan McIlwraith. Junior Historians The next generation of reporters Rhona Edinburgh (Radio Scotland) get to grips with stories from Brudenell their communities Our Story (Radio Presenter Mark Stephen hears Lynsey Moyes Edinburgh Scotland) the stories and histories of distinctive communities across Scotland. Somewhere Only Nicola Meighan discovers new Debbie McPhail Edinburgh We Know (Radio and sometimes surprising Scotland) insights about some of our best- loved household names as they reveal their strong connection to a particular place. -

Scotland's Propaganda

UK: £0.00 US: $0.00 Scotland’s Propaganda War: The Media and the 2014 Independence Referendum How biased were the Scottish and UK Media? Why they were biased? Why did it matter in 2014? Why will it matter less next time? ©Professor John Robertson @ thoughtcontrolscotland.com September 2015 Professor John Robertson, of University of the West of Scotland, provides a detailed account of the role the Scottish and UK media played in the Scottish Referendum Campaign. The book is based on his own research, which triggered a heated dispute with BBC Scotland, a summons to the Scottish Parliament and a storm of debate in social media. It also presents research by other academics and gives explanations for the findings from prominent theorists such as Noam Chomsky. Originally contracted to Welsh Academic Press in September 2014, the book is now released into the public domain after several infuriating delays and barriers of an inexplicable nature. This account of media bias in the coverage of the Scottish Referendum campaign goes beyond more journalistic impressions, from practitioners within the industry, to explain why it was so. It does this by revealing the true nature of influences on our media which are the result of unequal access to education and the interlocking of the resultant elites in finance, in ownership, in commercial directorships, in media directorships, in senior post-holders in journalism, in university leadership including professors, and, uniquely in Scotland, in the elites leading the Scottish and UK Labour parties. With love for Scotland and all its people and places - John Robertson, 24th August 2015. -

Karen Dunbar

22 Astwood Mews, London, SW7 4DE CDA +44 (0)20 7937 2749|[email protected] KAREN DUNBAR First Icon Awards in Glasgow, 2015 named ‘Role Model of the Year’. THEATRE THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING EARNEST ‘Lady Bracknell’ Dir. Lu Kemp [Perth Theatre] STILL GAME LIVE ‘God’ Dir. Michael Hines [SSE Hydro] CALENDAR GIRLS THE MUSICAL ‘Cora’ Dir. Matt Ryan [David Pugh Ltd/ UK Tour] MA, PA AND THE LITTLE MOUTHS ‘Ma’ Dir. Andy Arnold [Tron Theatre, Glasgow / Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh] #71 ‘Chrissy’ Dir. April Chamberlain [Òran Mór/ Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh] SHAKESPEARE TRILOGY Dir. Phyllida Lloyd The Tempest ‘Trinculo’ [Donmar Warehouse/ St Ann’s Warehouse, New York] Henry IV ‘Vernon/Bardolph’ [Donmar Warehouse] Julius Caesar [Donmar Warehouse] WITSHERFACE: FUNNY HOW…? [Glasgow International Comedy Festival at Saint Luke’s] PRISCILLA QUEEN OF THE DESERT THE MUSICAL ‘Shirley’ Dir. Simon Phillips/ Jason Capewell [David Ian Productions Ltd/ Edinburgh Playhouse] HENRY IV ‘Vernon/Bardolph’ Dir. Phyllida Lloyd [St Ann’s Warehouse, New York] Nominated Outstanding Revival of a Play, 61st Annual Drama Desk Awards, New York CYRANO DE BERGERAC ‘Minder’ Dir. Gerry Mulgrew [Edinburgh Book Festival/ Communicado Theatre Co] CAN’T FORGET ABOUT YOU ‘Martha’ Dir. Conleth Hill [Lyric Theatre, Belfast at the Tron Theatre, Glasgow 2015] HAPPY DAYS ‘Winnie’ Dir. Andy Arnold [Mayfesto - Tron Theatre, Glasgow] HENRY IV ‘Vernon/Bardolph’ Dir. Phyllida Lloyd [Donmar Warehouse] CAN’T FORGET ABOUT YOU ‘Martha’ Dir. Conleth Hill [Lyric Belfast] 2013 Studio Production, 2014 Main House Production THE GUID SISTERS ‘Rose Ouimet’ Dir. Serge Denoncourt [NTS at Lyceum, Edinburgh and Kings Theatre, Glasgow] Nominated Best Ensemble, Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland 2012 - 2013 MEN SHOULD WEEP [2010/2011] ‘Mrs Harris’ Dir. -

Children 1St FRS 10 V3

Children 1st Annual Report and Financial Statements 2016-17 1 | www.children1st.org.uk Table of Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Report of the Board of Management .................................................................................................................... 4 Objects and Activities .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Vision ................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Mission ............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Values .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Strategic Plan .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Achievements and Performance ........................................................................................................................... 5 Strategic Aim 1 - Providing excellent services which promote the -

Table of Membership Figures For

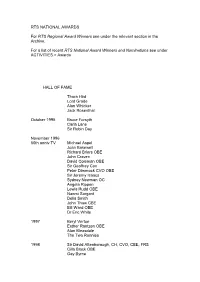

RTS NATIONAL AWARDS For RTS Regional Award Winners see under the relevant section in the Archive. For a list of recent RTS National Award Winners and Nominations see under ACTIVITIES > Awards HALL OF FAME Thora Hird Lord Grade Alan Whicker Jack Rosenthal October 1995 Bruce Forsyth Carla Lane Sir Robin Day November 1996 60th anniv TV Michael Aspel Joan Bakewell Richard Briers OBE John Craven David Coleman OBE Sir Geoffrey Cox Peter Dimmock CVO OBE Sir Jeremy Isaacs Sydney Newman OC Angela Rippon Lewis Rudd OBE Naomi Sargant Delia Smith John Thaw CBE Bill Ward OBE Dr Eric White 1997 Beryl Vertue Esther Rantzen OBE Alan Bleasdale The Two Ronnies 1998 Sir David Attenborough, CH, CVO, CBE, FRS Cilla Black OBE Gay Byrne David Croft OBE Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly Verity Lambert James Morris 1999 Sir Alistair Burnet Yvonne Littlewood MBE Denis Norden CBE June Whitfield CBE 2000 Harry Carpenter OBE William G Stewart Brian Tesler CBE Andrea Wonfor In the Regions 1998 Ireland Gay Byrne Brian Farrell Gloria Hunniford Gerry Kelly James Morris 1999 Wales Vincent Kane OBE Caryl Parry Jones Nicola Heywood Thomas Rolf Harris AM OBE Sir Harry Secombe CBE Howard Stringer 2 THE SOCIETY'S PREMIUM AWARDS The Cossor Premium 1946 Dr W. Sommer 'The Human Eye and the Electric Cell' 1948 W.I. Flach and N.H. Bentley 'A TV Receiver for the Home Constructor' 1949 P. Bax 'Scenery Design in Television' 1950 Emlyn Jones 'The Mullard BC.2. Receiver' 1951 W. Lloyd 1954 H.A. Fairhurst The Electronic Engineering Premium 1946 S.Rodda 'Space Charge and Electron Deflections in Beam Tetrode Theory' 1948 Dr D. -

Nominee List 2019

CELTIC MEDIA FESTIVAL - NOMINEE LIST 2019 CELTIC MEDIA FESTIVAL - NOMINEE LIST 2019 Title Production Company Broadcaster Country Animation Ar Pevarad Kerniel Vivement Lundi ! & La Boîte... BRITTANY Cumulus Ioan Holland WALES Peek Zoo Dream Logic RTÉ IRELAND Widdershins Simon P Biggs SCOTLAND Arts Lomax in Éírinn Aisling Productions Ltd TG4 IRELAND RIP IT UP: DIY or Die BBC Studios, Pacific Quay Productions BBC TWO Scotland SCOTLAND Sylvia Plath: Inside the Bell Jar Yeti Television BBC2 WALES The Cliff Top Sessions Clifftop Creative CORNWALL Children's Programme All In Good Time Dyehouse Films RTÉ 2 IRELAND Mabinogi-ogi Boom Cymru S4C WALES Leugh Le Linda BBC Gàidhlig BBC ALBA SCOTLAND Prosiect Z Boom Cymru S4C WALES Skiantou Sichant JPL FILMS France 3 Bretagne BRITTANY Comedy Elis James: Cic lan yr Archif Alpha S4C WALES O'r Diwedd 2017 Boom Cymru S4C WALES Scot Squad The Comedy Unit BBC Scotland SCOTLAND Soft Border Patrol The Comedy Unit BBC Northern Ireland IRELAND Two Doors Down BBC Studios BBC Two SCOTLAND Current Affairs Caso Diana Quer Televisión de Galicia Televisión de Galicia GALICIA Degemer mat France 3 Bretagne France 3 Bretagne BRITTANY Disclosure: Suffer the Children BBC Scotland BBC Scotland on One SCOTLAND Gangs, Murder and Teenage Drug Runners BBC Cymru Wales BBC One Wales WALES RTÉ Prime Time – Carers in Crisis RTÉ News and Current Affairs RTÉ One IRELAND Drama Series Bannan Young Films BBC ALBA SCOTLAND Can't Cope Won't Cope Deadpan Pictures RTÉ 2 IRELAND River City BBC Studios BBC Scotland SCOTLAND Un Bore Mercher Vox Pictures S4C WALES 1 CELTIC MEDIA FESTIVAL - NOMINEE LIST 2019 Entertainment Celtic Connections: Bothy Culture and Beyond BBC Scotland Music Ents & Events BBC2 Scotland SCOTLAND FFIT Cymru Cwmni Da S4C WALES Ireland's Fittest Family Animo Kite Production for RTÉ RTÉ One IRELAND Factual Entertainment An Drochaid MacTV BBC ALBA SCOTLAND Rhod Gilbert's Work Experience Zipline Media Limited BBC One Wales WALES Taithí gan Teorainn Loosehorse TG4 IRELAND The Rotunda Scratch Films Ltd.