Totalitarian Insurgency: Evaluating the Islamic State's In-Theater Propaganda Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—And Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 29 | Issue 1 Article 6 3-20-2017 The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the International Relations Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Public Policy Commons, and the Terrorism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Ramakrishna, Kumar (2017) "The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 29 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol29/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New England Journal of Public Policy The Growth of ISIS Extremism in Southeast Asia: Its Ideological and Cognitive Features—and Possible Policy Responses Kumar Ramakrishna S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore This article examines the radicalization of young Southeast Asians into the violent extremism that characterizes the notorious Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). After situating ISIS within its wider and older Al Qaeda Islamist ideological milieu, the article sketches out the historical landscape of violent Islamist extremism in Southeast Asia. There it focuses on the Al Qaeda-affiliated, Indonesian-based but transnational Jemaah Islamiyah (JI) network, revealing how the emergence of ISIS has impacted JI’s evolutionary trajectory. -

Depliant English.Pdf

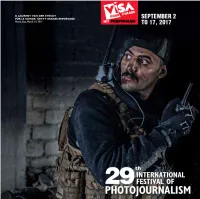

EDITORIAL Can there be too much coverage of a conflict? The question may seem disrespectful, but it still needs to be asked, and answered. Page The program at Visa pour l’Image this year 4 features three exhibitions on the battle EXHIBITIONS for Mosul: Laurent Van der Stockt for Le Admission free of charge, Monde, Alvaro Canovas for Paris Match, and Lorenzo Meloni for Magnum Photos, every day from 10 am with Meloni having a more general approach to 8 pm, Saturday, presenting the collapse of the caliphate. The September 2 brutality of the attacks and the geopolitical , issues involved are so critical that the battle to Sunday certainly deserves attention, and extended September 17 attention. So there are three exhibitions: of a total of 25, three are on the battle for Mosul. As André Gide said: “Everything has already Page been said, but as no one was listening, it has 30 to be said all over again.” At Visa pour l’Image, our ambition is to show EVENING SHOWS and see the whole world, and so we have Monday, September wondered why, of the thirty or so armed 4 to Saturday, conflicts around the world, only a small September 9, 9.45 pm number are covered by a large proportion at Campo Santo of photojournalists. Of the many stories submitted and reviewed by our teams, a few dozen, either directly or indirectly, have VISA D’OR been on Mosul. And for the first time ever in AWARDS the history of the festival, the four nominees & All the awards for the Paris Match Visa d’or News award are on the same subject: Mosul. -

Why Concessions Should Not Be Made to Terrorist Kidnappers

European Journal of Political Economy 44 (2016) 41–52 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect European Journal of Political Economy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ejpe Why concessions should not be made to terrorist kidnappers Patrick T. Brandt, Justin George, Todd Sandler ⁎ School of Economic, Political & Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA article info abstract Article history: This paper examines the dynamic implications of making concessions to terrorist kidnappers. Received 21 December 2015 We apply a Bayesian Poisson changepoint model to kidnapping incidents associated with Received in revised form 23 May 2016 three cohorts of countries that differ in their frequency of granting concessions. Depending Accepted 24 May 2016 on the cohort of countries during 2001–2013, terrorist negotiation successes encouraged 64% Available online 26 May 2016 to 87% more kidnappings. Our findings also hold for 1978–2013, during which these negotia- tion successes encouraged 26% to 57% more kidnappings. Deterrent aspects of terrorist casual- Keywords: ties are also quantified; the dominance of religious fundamentalist terrorists meant that such Kidnappings casualties generally did not curb kidnappings. Changepoints © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY- Game theory Concessions NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Violent ends Dynamic analysis “…we know that hostage takers looking for ransoms distinguish between those governments that pay ransoms and those that do not, and make a point of not taking hostages from those countries that do not pay.” David S. Cohen, US Under Secretary for Terrorism and Financial Intelligence, 2012 speech to ChathamHouse [Callimachi (2014a)] 1. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

The Limits of Military Counterrevolution

THE LIMITS OF MILITARY COUNTERREVOLUTION jason brownlee merica’s recent wars in South Asia and the Middle East have A inflicted extraordinary physical damage and wreaked seemingly endless havoc. Operations in Afghanistan and Iraq during 2001–2014 totaled $1.6 trillion.1 Once long-term veterans’ care, disability payments, and other economic effects are included, estimates rise to $4–$6 tril- lion.2 Related reports count over one million Americans wounded in Afghanistan and Iraq, in addition to nearly seven thousand killed.3 A conservative tally of local civilian casualties in these countries reaches the hundreds of thousands. Mass destruction has not brought political order to Kabul, Baghdad, or (if one adds the 2011 Libya war) Tripoli. 1 Amy Belasco, The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Opera- tions Since 9/11 (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service, 2014). 2 Neta C Crawford, US Budgetary Costs of Wars through 2016: $4.79 Trillion and Counting (Providence, RI: Watson Institute of International and Public Affairs, Brown University, 2016). 3 Jamie Reno, “VA Stops Releasing Data On Injured Vets as Total Reaches Grim Mile- stone,” International Business Times (2013). http://icasualties.org/ All subsequent data on US casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq come from this source. 151 CATALYST • VOL 2 • №2 Dictatorship has been followed by civil war and interstate conflict among regional powers. These conflagrations present a historic opportunity for correcting US policy, but mainstream critiques have been stunningly myopic. At the peak of government, foreign policy learning remains more self-exculpatory than self-reflective. The cutting-edge diagnosis is that proper “counterinsurgency” requires a more serious political commit- ment than what Washington made in 2001–2016. -

The UK's Experience in Counter-Radicalization

APRIL 2008 . VOL 1 . ISSUE 5 The UK’s Experience in published in October 2005, denied having “neo-con” links and supporting that Salafist ideologies played any role government anti-terrorism policies.4 Counter-Radicalization in the July 7 bombings and blamed Rafiq admitted that he was unprepared British foreign policy, the Israeli- for the hostility—or effectiveness—of By James Brandon Palestinian conflict and “Islamophobia” these Islamist attacks: for the attacks.1 They recommended in late april, a new British Muslim that the government tackle Islamic The Islamists are highly-organized, group called the Quilliam Foundation, extremism by altering foreign policy motivated and well-funded. The th named after Abdullah Quilliam, a 19 and increasing the teaching of Islam in relationships they’ve made with century British convert to Islam, will be schools. Haras Rafiq, a Sufi member of people in government over the last launched with the specific aim of tackling the consultations, said of the meetings: 20 years are very strong. Anyone “Islamic extremism” in the United “It was as if they had decided what their who wants to go into this space Kingdom. Being composed entirely findings were before they had begun; needs to be thick-skinned; you of former members of Hizb al-Tahrir people were just going through the have to realize that people will lie (HT, often spelled Hizb ut-Tahrir), the motions.”2 about you; they will do anything global group that wants to re-create to discredit you. Above all, the the caliphate and which has acted as Sufi Muslim Council attacks are personal—that’s the a “conveyor belt” for several British As a direct result of witnessing the way these guys like it. -

PHOTOJOURNALISM EDITORIAL Can There Be Too Much Coverage of a Conflict? the Question May Seem Disrespectful, but It Still Needs to Be Asked, and Answered

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN © LAURENT VAN DER STOCKT Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais, 66000 Perpignan FOR LE MONDE/ Getty ImaGeS ReportaGe SEPTEMBER 2 Tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 Mosul, Iraq, March 19, 2017 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan TO 17, 2017 @Visapourlimage PRESIDENT JEAN-PAUL GRIOLET VICE-PRESIDENT / TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE COORDINATION ARNAUD FÉLICI ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) ANAÏS MONTELS & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN PRESS / PUBLIC RELATIONS 2E BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris Tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] www.2e-bureau.com DIRECTOR SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT / ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, CLÉMENCE ANEZOT TATIANA FOKINA, CAMILLE GRENARD, DANIELA JACQUET FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B 75003 Paris Tel : +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANT LOUIS MARTINEZ SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDANCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR EVENING SHOWS, EVENING PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE SONIA CHIRONI EVENING PRESENTATIONS PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & CAPTIONS BÉATRICE LEROY BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY COMMUNITY MANAGER KYLA WOODS -

Chapter 20 Section 3

CHAPTER 20 SECTION 3 Oil and strategic trading lands have continued to be sources of conflict in the Middle East o United States and Soviets fought for control during the Cold War o Western countries continue to want control today Israel’s creation by the United Nations in 1948 was not recognized by Arabs in Palestine, leading to many conflicts still continuing today o Three wars 1956, 1967, and 1973 . Leads to Israel gaining more land; While between wars, Israelis faced terrorist attacks; United States continually attempts to make peace, unsuccessfully . 1967 war Israeli military takes control of the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, and Golan Heights from Syria . 1973/Yom Kippur War Arabs surpassingly attacked on Yom Kippur, but still could not take back occupied lands; Israelis begin housing Jewish people in occupied lands o Palestine Liberation Organization leads Arab fight against Israel . Led by Yasir Arafat; Extreme dislike of Israelis, and wanted to destroy Israel; Attacked Israel numerous times; Airplane hi-jacking and Olympic killings . In 1987, Arabs in Israel-occupied lands attempt to revolt; Using suicide bombers and terroristic attacks, with many Israelis and Arabs dying o United States and United Nations have attempted to bring peace to the region . Golda Meir was in peace talks in 1973 when Arabs attacked; Peace Accord signed in 1979, giving Sinai Peninsula back to Egypt; Jordan makes peace with Israel in 1994; Syria and Israel continue to fight over Golan Heights . Oslo Accords, signed in 1993 by Yasir Arafat and Israeli leader Yitzhak Rabin gave Palestinians in Gaza and West Bank limited self-rule, and recognition by Israel, and Palestinian Liberation Organization stops terrorist Attacks on Israel o Even with pledge by Mahmoud Abbas, Palestinian violence on Israelis continued . -

1. the Big Picture Maintained and They Will Continue to Receive Salaries Then Further IS Attack Exposes Gaps in Oil Crescent Security Posture Endorsements Are Likely

THe Government of National Accord (GNA) Has yet to move into Tripoli despite claims by Prime Minister designee, Fayez Seraj, tHeir entry was imminent in a television interview given on Mar 17. Libya Weekly Similar announcements Have been made previously. WHispering Bell is aware of Political Security GNA attempts to negotiate safe entry into tHe capital, and tHat many Tripoli-based Bell Update Whispering Bell militias are gradually supporting tHis, July 30, 2018 albeit not always publicly. If tHe GNA can ensure tHat local militias are consulted prior to entrance, tHeir security role will be 1. The Big Picture maintained and tHey will continue to receive salaries tHen furtHer IS attack exposes gaps in Oil Crescent security posture endorsements are likely. Also, in a positive development for tHe unity THis week was marked by an Islamic Following tHe attack, tHe LNA launched a government leaders claiming to represent State (IS) attack on tHe Al-Aguila police “counter offensive” resulting in tHe deatH various civil groups and local militias from station, located approximately 75 kms of an unknown number of militants in tHe Sabrata, Surman, Ajaylat, Riqdalin and East of Ras Lanuf, in addition to an Wadi Al-Jafr area. Pictures were Al-Jmail reportedly declared tHeir support unidentified drone strike targeting a circulated across social media outlets for tHe GNA. Similarly, Misrata’s farmHouse in Awbari, SoutH of Libya. The purportedly showing tHe bodies of 13 IS Municipality also released a statement latest IS Hit-and-run operation raises attackers. CONTENTS endorsing tHe government. THe UNSMIL concerns over tHe Libyan National Army’s also announced its decisions “to extend (LNA) ability to secure tHe Oil Crescent MeanwHile, multiple veHicles belonging to 1 until 15 June 2016 the mandate...to area after it recently mobilized forces. -

Reporting ISIS

Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series #D-101, July 2016 The Pen and the Sword: Reporting ISIS By Paul Wood Joan Shorenstein Fellow, Fall 2015 BBC Middle East Correspondent Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. May 2013: The kidnapping started slowly. 1 At first, it did not feel like a kidnapping at all. Daniel Rye delivered himself to the hostage-takers quite willingly. He was 24 years old, a freelance photographer from Denmark, and he had gone to the small town of Azaz in northern Syria. His translator, a local woman, said they should get permission to work. So on the morning of his second day in Azaz, only his second ever in Syria, they went to see one of the town’s rebel groups. He knocked at the metal gate to a compound. It was opened by a boy of 11 or 12 with a Kalashnikov slung over his shoulder. “We’ve come to see the emir,” said his translator, using the word – “prince” – that Islamist groups have for their commanders. The boy nodded at them to wait. Daniel was tall, with crew-cut blonde hair. His translator, a woman in her 20s with a hijab, looked small next to him. The emir came with some of his men. He spoke to Daniel and the translator, watched by the boy with the Kalashnikov. The emir looked through the pictures on Daniel’s camera, squinting. There were images of children playing on the burnt-out carcass of a tank. It was half buried under rubble from a collapsed mosque, huge square blocks of stone like a giant child’s toy. -

Appendix C: Military Operations and Planning Scenarios Referred to in This Report

Appendix C: Military Operations and Planning Scenarios Referred to in This Report In describing the past and planned use of various types conducted on the territory of North Vietnam during of forces, this primer mentions a number of military the war (as opposed to air operations in South Vietnam, operations that the United States has engaged in since which were essentially continuous in support of U.S. World War II, as well as a number of scenarios that and South Vietnamese ground forces). The most nota- the Department of Defense has used to plan for future ble campaigns included Operations Rolling Thunder, conflicts. Those operations and planning scenarios are Linebacker, and Linebacker II. summarized below. 1972: Easter Offensive.This offensive, launched by Military Operations North Vietnamese ground forces, was largely defeated 1950–1953: Korean War. U.S. forces defended South by South Vietnamese ground forces along with heavy air Korea (the Republic of Korea) from an invasion by support from U.S. forces. North Korea (the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). North Korean forces initially came close to 1975: Spring Offensive.This was the final offensive overrunning the entire Korean Peninsula before being launched by North Vietnamese ground forces during the pushed back. Later, military units from China (the war. Unlike in the Easter Offensive, the United States People’s Republic of China) intervened when U.S. forces did not provide air support to South Vietnamese ground approached the Chinese border. That intervention caused forces, and North Vietnamese forces fully conquered the conflict to devolve into a stalemate at the location of South Vietnam. -

THE IMPACT of the IRAQ WAR on ISRAEL's NATIONAL SECURITY CONCEPTION by Jonathan Spyer*

THE IMPACT OF THE IRAQ WAR ON ISRAEL'S NATIONAL SECURITY CONCEPTION By Jonathan Spyer* Abstract: This article deals with the effects and implications of the Iraq War, and the current situation of insurgency in that country, on Israel's perception of its national security. Specifically, it examines the extent to which the war has impacted on and transformed the three tiers of threat facing Israel--namely the irregular, conventional and non-conventional levels of warfare. The article outlines the nature of each of these three levels of threat, observing the impact of the Iraq War on it. It then moves toward some general conclusions on the Iraq War of 2003 and the events that have followed it as viewed through the perception of Israeli thinking on the region. In each area, this article observes the responses emerging from the Israeli strategic and policymaking echelon to the new situation opened up by the war of 2003. In this regard, it considers Israel's current unilateralist turn in the context of the broader view of current political trends in the region which prevails in the Israeli policymaking echelon. Israel is a country unique among members same dispensation, the same regimes, the of the modern states' system in that the same prevailing ideas, often even the same basic legitimacy of its existence as a individuals (or their sons) dominate the sovereign body is rejected by its neighbors. region as did so in the late 1970s. The dominant political currents of the The region remains stymied by Middle Eastern region place the perception economic stagnation, and the failure of the of Israel as a foreign, illegitimate implant in regimes to develop the potential of the the Middle East somewhere near the center populations under their control.