Unframe Malevich!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy Regained: Niko and the Russian Avant-Garde

A LEGACY REGAINED: NIKO AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE PALACE EDITIONS Contents 8 Foreword Evgeniia Petrova 9 Preface Job de Ruiter 10 Acknowledgements and Notes to the Reader John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny 13 Introduction John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny Part I. Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Russian Avant Garde Remembering Nikolai Khardzhiev 21 Nikolai Khardzhiev RudolfDuganov 24 The Future is Now! lra Vrubel-Golubkina 36 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Suprematists Nina Suetina 43 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Maiakovsky Museum, Moscow Gennadii Aigi 50 My Memoir of Nikolai Khardzhiev Vyacheslav Ivanov 53 Nikolai Khardzhiev and My Family Zoya Ender-Masetti 57 My Meetings with Nikolai Khardzhiev Galina Demosfenova 59 Nikolai Khardzhiev, Knight of the Avant-garde Jean-C1aude Marcade 63 A Sole Encounter Szymon Bojko 65 The Guardian of the Temple Andrei Nakov 69 A Prophet in the Wilderness John E. Bowlt 71 The Great Commentator, or Notes About the Mole of History Vasilii Rakitin Writings by Nikolai Khardzhiev Essays 75 Autobiography 76 Poetry and Painting:The Early Maiakovsky 81 Cubo-Futurism 83 Maiakovsky as Partisan 92 Painting and Poetry Profiles ofArtists and Writers 99 Elena Guro 101 Boris Ender 103 In Memory of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov 109 Vladimir Maiakovsky 122 Velimir Khlebnikov 131 Alexei Kruchenykh 135 VladimirTatlin 137 Alexander Rodchenko 139 EI Lissitzky Contents Texts Edited and Annotated by Nikolai Khardzhiev 147 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introductions to Kazimir Malevich's Autobiography (Parts 1 and 2) 157 Kazimir Malevieh Autobiography 172 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Mikhail Matiushin's The Russian Cubo-Futurists 173 Mikhail Matiushin The Russian Cubo-Futurists 183 Alexei Morgunov A Memoir 186 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Khlebnikov Is Everywhere! 187 Khlebnikov is Everywhere! Memoirs by Oavid Burliuk, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Amfian Reshetov, and on Osip Mandelshtam 190 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Lev Zhegin's Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin 192 Lev Zhegin Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin Part 11. -

Painting the Absolute

ANDRÉI NAKOV MALEVICH painting the absolute An iconic figure in the history of modern art, the Russian painter Kazimir Malevich (1879-1935) was the creator of Suprematism, best known for his emblematic Black Square (1915). Censored in Russia for many years, his revolutionary writings were only recognised at the end of the twentieth century, initially in Western Europe. Similarly, much of his work remained unknown until the fall of Communism; little studied, the life and work of this painter remain shrouded in an aura of mystery. Andréi Nakov’s monumental study of this prophetic artist is founded on many decades of research in Russia, Western Europe and the US. The author has uncovered many previously unknown documents, and sheds a new light on Malevich’s pivotal role in the development of modern art, offering a radically new interpretation of a • Andréi Nakov and Malevich’s daughter, Anna-Maria Uriman. fascinating artist. Andréi Nakov is the leading world expert on the work of Kazimir Malevich and the ‘The Essential 4-volume Reference Guide to Melevich’s Complete Oeuvre’ Russian avant garde. He is the author of the Malevich catalogue raisonné (2002), an extensive critical anthology of the writings of Malevich (1975), and L’Avant-garde • The most detailed and comprehensive analysis of Malevich’s complete œuvre available Russe (1984). Kazimir Malevich: Le Peintre Absolu (the French edition of the present • Based on over 30 years of research in Russia, Western Europe and the US book) was awarded a prize in 2007 by the Académie francaise des Beaux-Arts. Andréi • Andréi Nakov’s scrupulous research corrects previous errors, myths and Nakov has organised numerous exhibitions on Dada, Constructivism and abstract art, misinterpretations of Malevich’s work including the Tate Gallery’s Malevich exhibition in 1976. -

El Lissitzky Letters and Photographs, 1911-1941

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6r29n84d No online items Finding aid for the El Lissitzky letters and photographs, 1911-1941 Finding aid prepared by Carl Wuellner. Finding aid for the El Lissitzky 950076 1 letters and photographs, 1911-1941 ... Descriptive Summary Title: El Lissitzky letters and photographs Date (inclusive): 1911-1941 Number: 950076 Creator/Collector: Lissitzky, El, 1890-1941 Physical Description: 1.0 linear feet(3 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The El Lissitzky letters and photographs collection consists of 106 letters sent, most by Lissitzky to his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, along with his personal notes on art and aesthetics, a few official and personal documents, and approximately 165 documentary photographs and printed reproductions of his art and architectural designs, and in particular, his exhibition designs. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German Biographical/Historial Note El Lissitzky (1890-1941) began his artistic education in 1909, when he traveled to Germany to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Darmstadt. Lissitzky returned to Russia in 1914, continuing his studies in Moscow where he attended the Riga Polytechnical Institute. After the Revolution, Lissitzky became very active in Jewish cultural activities, creating a series of inventive illustrations for books with Jewish themes. These formed some of his earliest experiments in typography, a key area of artistic activity that would occupy him for the remainder of his life. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

Dvigubski Full Dissertation

The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Anna Dvigubski All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Figured Author: Authorial Cameos in Post-Romantic Russian Literature Anna Dvigubski This dissertation examines representations of authorship in Russian literature from a number of perspectives, including the specific Russian cultural context as well as the broader discourses of romanticism, autobiography, and narrative theory. My main focus is a narrative device I call “the figured author,” that is, a background character in whom the reader may recognize the author of the work. I analyze the significance of the figured author in the works of several Russian nineteenth- and twentieth- century authors in an attempt to understand the influence of culture and literary tradition on the way Russian writers view and portray authorship and the self. The four chapters of my dissertation analyze the significance of the figured author in the following works: 1) Pushkin's Eugene Onegin and Gogol's Dead Souls; 2) Chekhov's “Ariadna”; 3) Bulgakov's “Morphine”; 4) Nabokov's The Gift. In the Conclusion, I offer brief readings of Kharms’s “The Old Woman” and “A Fairy Tale” and Zoshchenko’s Youth Restored. One feature in particular stands out when examining these works in the Russian context: from Pushkin to Nabokov and Kharms, the “I” of the figured author gradually recedes further into the margins of narrative, until this figure becomes a third-person presence, a “he.” Such a deflation of the authorial “I” can be seen as symptomatic of the heightened self-consciousness of Russian culture, and its literature in particular. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Download File

Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2014 © 2014 Anita Tárnai All rights reserved ABSTRACT Cultural Experimentation as Regulatory Mechanism in Response to Events of War and Revolution in Russia (1914-1940) Anita Tárnai From 1914 to 1940 Russia lived through a series of traumatic events: World War I, the Bolshevik revolution, the Civil War, famine, and the Bolshevik and subsequently Stalinist terror. These events precipitated and facilitated a complete breakdown of the status quo associated with the tsarist regime and led to the emergence and eventual pervasive presence of a culture of violence propagated by the Bolshevik regime. This dissertation explores how the ongoing exposure to trauma impaired ordinary perception and everyday language use, which, in turn, informed literary language use in the writings of Viktor Shklovsky, the prominent Formalist theoretician, and of the avant-garde writer, Daniil Kharms. While trauma studies usually focus on the reconstructive and redeeming features of trauma narratives, I invite readers to explore the structural features of literary language and how these features parallel mechanisms of cognitive processing, established by medical research, that take place in the mind affected by traumatic encounters. Central to my analysis are Shklovsky’s memoir A Sentimental Journey and his early articles on the theory of prose “Art as Device” and “The Relationship between Devices of Plot Construction and General Devices of Style” and Daniil Karms’s theoretical writings on the concepts of “nothingness,” “circle,” and “zero,” and his prose work written in the 1930s. -

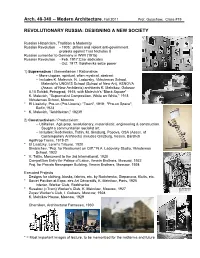

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

Rayonists and Futurists: a Manifesto, 1913

MIKHAIL LARIONOV AND NATALYA GONCHAROVA Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 For biographies see pp. 79 and 54. The text of this piece, "Luchisty i budushchniki. Manifest," appeared in the miscel- lany Oslinyi kkvost i mishen [Donkey's Tail and Target] (Moscow, July iQn), pp. 9-48 [bibl. R319; it is reprinted in bibl. R14, pp. 175-78. It has been translated into French in bibl. 132, pp. 29-32, and in part, into English in bibl. 45, pp. 124-26]. The declarations are similar to those advanced in the catalogue of the '^Target'.' exhibition held in Moscow in March IQIT fbibl. R315], and the concluding para- graphs are virtually the same as those of Larionov's "Rayonist Painting.'1 Although the theory of rayonist painting was known already, the "Target" acted as tReTormaL demonstration of its practical "acKieveffllBnty' Becau'S^r^ffie^anous allusions to the Knave of Diamonds. "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," and David Burliuk, this manifesto acts as a polemical гейроп^ ^Х^ШШУ's rivals^ The use of the Russian neologism ШШ^сТиШ?, and not the European borrowing futuristy, betrays Larionov's current rejection of the West and his orientation toward Russian and East- ern cultural traditions. In addition to Larionov and Goncharova, the signers of the manifesto were Timofei Bogomazov (a sergeant-major and amateur painter whom Larionov had befriended during his military service—no relative of the artist Alek- sandr Bogomazov) and the artists Morits Fabri, Ivan Larionov (brother of Mikhail), Mikhail Le-Dantiyu, Vyacheslav Levkievsky, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romano- vich, Aleksandr Shevchenko, and Kirill Zdanevich (brother of Ilya). -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

Detki V Kletke: the Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry

Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Morse, Ainsley. 2016. Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493521 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry A dissertation presented by Ainsley Elizabeth Morse to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Ainsley Elizabeth Morse. All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephanie Sandler Ainsley Elizabeth Morse Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry Abstract Since its inception in 1918, Soviet children’s literature was acclaimed as innovative and exciting, often in contrast to other official Soviet literary production. Indeed, avant-garde artists worked in this genre for the entire Soviet period, although they had fallen out of official favor by the 1930s. This dissertation explores the relationship between the childlike aesthetic as expressed in Soviet children’s literature, the early Russian avant-garde and later post-war unofficial poetry. -

DANIIL KHARMS and the POETICS of the ABSURD by the Same Author V

DANIIL KHARMS AND THE POETICS OF THE ABSURD By the same author V. F. Odoyevsky: his fife, times and milieu (1986) Pasternak's 'Dr Zhivago' (1987) Daniil Kharms: The Plummeting Old Women (trans.) (1989) The Literary Fantastic: from Gothic to Postmodernism (1990) Daniil Kharms and the Poetics of the Absurd Essays and Materials Edited by N eil Cornwell Senior Lecturer in Russian Studies University 01 Bristol Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-11644-7 ISBN 978-1-349-11642-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-11642-3 © Neil Cornwell 1991 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1991 978-0-333-52590-6 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1991 ISBN 978-0-312-06177-7 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Daniil Kharms and the poetics of the absurd: essays and materials I edited by Neil Cornwell. p. cm. Majority of the essays translated from Russian. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 978-0-312-06177-7 1. Kharms, Daniil, 1905-1942-Criticism and interpretation. 2. Absurd (Philosophy) in literature. 1. Cornwell, Neil. PG3476.K472Z65 1991 89 1. 78 '4209-dc20 91-7702 CIP Contents An unpublished relie of Daniil Kharms vii Robin Milner-Gulland Aeknowledgements ix Note on Transliteration and Abbreviations x Epigraph: Aleksandr Galieh, Legenda 0 tabake xii Notes on the Contributors xv PART I: INTRODUCTORY 1 Introduetion: Daniil Kharms, Blaek Miniaturist 3 Neil Cornwell