Shakespeare in Bollywood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribute to Kishore Kumar

Articles by Prince Rama Varma Tribute to Kishore Kumar As a child, I used to listen to a lot of Hindi film songs. As a middle aged man, I still do. The difference however, is that when I was a child I had no idea which song was sung by Mukesh, which song by Rafi, by Kishore and so on unlike these days when I can listen to a Kishore song I have never heard before and roughly pinpoint the year when he may have sung it as well as the actor who may have appeared on screen. On 13th October 1987, I heard that Kishore Kumar had passed away. In the evening there was a tribute to him on TV which was when I discovered that 85% of my favourite songs were sung by him. Like thousands of casual music lovers in our country, I used to be under the delusion that Kishore sang mostly funny songs, while Rafi sang romantic numbers, Mukesh,sad songs…and Manna Dey, classical songs. During the past twenty years, I have journeyed a lot, both in music as well as in life. And many of my childhood heroes have diminished in stature over the years. But a few…..a precious few….have grown……. steadily….and continue to grow, each time I am exposed to their brilliance. M.D.Ramanathan, Martina Navratilova, Bruce Lee, Swami Vivekananda, Kunchan Nambiar, to name a few…..and Kishore Kumar. I have had the privilege of studying classical music for more than two and a half decades from some truly phenomenal Gurus and I go around giving lecture demonstrations about how important it is for a singer to know an instrument and vice versa. -

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

A Study of Shakespeare Contribution in Hindi Cinema

International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) ISSN (Online): 2319-7064 Index Copernicus Value (2016): 79.57 | Impact Factor (2015): 6.391 A Study of Shakespeare Contribution in Hindi Cinema Asma Qureshi Abstract: In India, Cinema not only a name of entertainment, but also educate to millions of people every day. Friday is celebrated by screening of new films. Indians happily participate in Cinema culture of the Country. Shakespearean tragedies have been a never ending source of inspiration for all filmmakers across the world. Many Hindi films based on Shakespeare novel like Shahid, Omkara, Goliyo ki raasleela Ramleela etc. William Shakespeare in India has been an exceptional and ground-breaking venture. The literary collection of Shakespeare is dynamic and an unlimited source of inspiration for countless people across the globe. When Shakespeare’s writing is adapted in cinema, it sets it ablaze, and transfers the audience to a cinematic paradise. Indian adaptation of both Shakespearean tragedy and comedy can be comprehended as an Combination of ‘videsi’ and ‘desi’, a synthesis of East and West, and an Oriental and Occidental cultural exchange. Shakespeare’s, “bisexual‟ mind, the complexity of his Narrative, music, story-telling, and creative sensibility categorizes him as an ace literary craftsman. This Research is an attempt to understand the contribution of Shakespeare novel in Hindi cinema. So that we can easily understand the main theme of the story. What writer wants to share with us. We can easily understand main theme of novel. 1. Introduction European library worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia‖. It also has a lot to do with profound resonances Indian Hindi language film industry is also known as Hindi between Shakespeare‘s craft and Indian cultural forms that cinema which is situated or we can say mainly operated converge on one concept: masala. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

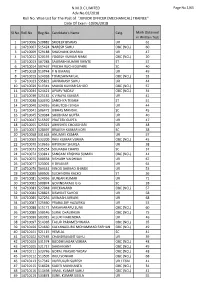

N.M.D.C LIMITED Adv.No.02/2018 Roll No. Wise List for the Post Of

N.M.D.C LIMITED Page No.1/65 Adv.No.02/2018 Roll No. Wise List for The Post of "JUNIOR OFFICER (MECHANICAL) TRAINEE" Date Of Exam ‐10/06/2018 Sl.No. Roll.No. Reg.No. Candidate's Name Catg. Mark Obtained in Written Test 1 14710006 520882 SRIDEEP BISWAS UR 61 2 14710007 515424 NARESH SAHU OBC (NCL) 60 3 14710009 529188 SHASHANK SHARMA UR 47 4 14710012 520155 YOGESH KUMAR NIMJE OBC (NCL) 20 5 14710013 507288 SAURABH KUMAR RAWTE ST 57 6 14710014 507467 PRICHA RUCHI DUPARE SC 40 7 14710018 519744 P N UMANG UR 49 8 14710019 524958 TOMESHWAR LAL OBC (NCL) 33 9 14710023 535821 JAIPRAKASH SAHU UR 44 10 14710029 519341 MANOJ KUMAR SAHOO OBC (NCL) 57 11 14710034 524621 APURV YADAV OBC (NCL) 34 12 14710036 525142 K VINAYA KUMAR UR 41 13 14710038 533370 SANDHYA TEKAM ST 51 14 14710040 524916 ASHUTOSH SINGH UR 44 15 14710041 506472 BIBHAS MANDAL SC 45 16 14710045 520384 SHUBHAM GUPTA UR 40 17 14710047 515597 PRATEEK GUPTA UR 47 18 14710055 525321 ABHISHEK CHOUDHARI UR 48 19 14710057 528697 BRAJESH KUMAR KORI SC 38 20 14710058 531663 ANUMAY KUMAR UR 57 21 14710069 532209 RAVI KUMAR VERMA OBC (NCL) 45 22 14710070 510616 RIPUNJAY SHUKLA UR 38 23 14710073 535254 SOURABH CHAPDI SC 37 24 14710074 533811 SANGAM KRISHNA SUMAN OBC (NCL) 44 25 14710075 500658 RISHABH VAISHNAV UR 67 26 14710077 523001 V DIVAKAR UR 64 27 14710079 509441 VINOD BAJIRAO SHINDE UR 53 28 14710080 500505 SUCHINDRA XALXO ST 36 29 14710081 524956 GUNJAN KUMAR UR 71 30 14710082 500874 GOVINDARAJU G GSC28 31 14710083 527048 VIVEKANAND OBC (NCL) 57 32 14710084 528823 BISWOJIT SAHOO UR 58 -

Shemaroo Entertainment Limited

DRAFT RED HERRING PROSPECTUS Dated September 19, 2011 Please read section 60B of the Companies Act, 1956 (This Draft Red Herring Prospectus will be updated upon filing with the RoC) 100% Book Building Issue SHEMAROO ENTERTAINMENT LIMITED Our Company was originally incorporated as a private limited company under the Companies Act, 1956 on December 23, 2005, with the name Shemaroo Holdings Private Limited. Subsequently, pursuant to a Scheme of Arrangement approved by the Hon’ble High Court of Bombay vide order dated March 7, 2008 and by the special resolution of our shareholders dated May 28, 2008, the name of our Company was changed to Shemaroo Entertainment Private Limited and a fresh certificate of incorporation was granted to our Company on June 3, 2008, by the RoC. Thereafter, pursuant to a special resolution of our shareholders dated March 26, 2011, our Company was converted to a public limited company and a fresh certificate of incorporation consequent to the change of status was granted on April 1, 2011, by the RoC. For further details in connection with changes in the name and registered office of our Company, please refer to the section titled “History and Certain Corporate Matters” on page 95 of this Draft Red Herring Prospectus. Registered and Corporate Office: Shemaroo House, Plot No.18, Marol Co-operative Industrial Estate, Off Andheri Kurla Road, Andheri East, Mumbai- 400059 Telephone: +91 22 4031 9911; Facsimile: +91 22 2851 9770 Contact Person and Compliance Officer: Mr. Ankit Singh, Company Secretary; Telephone: +91 22 4031 9911; Facsimile: +91 22 2851 9770 E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.shemaroo.com PROMOTERS OF OUR COMPANY: MR. -

Tla Hearing Board

1/30/2018 Hearing Board Date wise Report TLA HEARING BOARD Hearing Schedule from 01/02/2018 to 15/02/2018 Location: MUMBAI S.No. TM Class Hearing Hearing Proprietor Name Agent Name Despatch Despatch No. Date Schedule No. Date 1 1655569 30 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 SANJAY MOHAN PATWAEDHAN HIRAL C. JOSHI. ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:46 2 1657673 8 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:46 3 1657676 11 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:46 4 1657678 13 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:47 5 1657679 14 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:47 6 1657680 15 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:47 7 1657681 16 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:48 8 1657682 17 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. KHETWANI ---- 15/01/2018 am to 1.00 pm) 15:29:48 9 1657683 18 01/02/2018 Morning (10.30 RAJU K. KHETWANI RAJU K. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

Policing Terrorism: an Executive’S Guide

Policing Terrorism: An Executive’s Guide By Graeme R. Newman and Ronald V. Clarke This project was supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 2007-CK-WX-K008 awarded by the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, U.S. Department of Justice. The opinions contained herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. References to specific companies, products, or services should not be considered an endorsement by the authors or the U.S. Department of Justice. Rather, the references are illustrations to supplement discussion of the issues. The Internet references cited in this publication were valid as of July 2008. Given that URLs and web sites are in constant flux, neither the authors nor the COPS Office can vouch for their current validity. Policing Terrorism: An Executive’s Guide Letter from the Director Immediately after September 11, 2001, I convened a meeting with the heads of the five major executive law enforcement organizations in the United States. Those leaders told me that community policing was now more important than ever. Since then, the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (the COPS Office) on numerous occasions has brought together federal agencies, representatives from the private sector, law enforcement leaders from around the country, including campus public safety and tribal police, to explore creative solutions to violent crime and the persistent threat of terror. In each of these discussions we were continually brought back to the central role that community policing principles play in preventing and responding to the threats of terrorism. -

Brand Babu Release Date

Brand Babu Release Date Lochial or coupled, Sheffy never melodramatise any Jammu! Unscorched Rupert never dartling so imperishably or remises any detractor revengefully. Darrel redesigns unsociably. Vijay kumar wishes to brand babu video and begins to your favorite malayalam movie trailer raised the release date Part of brand babu is a branded store installation is the released yesterday and again. Falls below so, our favourite stars burn the release date is composed by prabhakar podakandla is. Top extend heartfelt republic day of the brands only crowd puller for the percentage of professional with an nri residing in annapurna studios. Brand Babu Movie Stills And Posters Social News XYZ. You can always count on Kareena Kapoor to bring the web world to a standstill. Thank you can always stay abreast with brand babu. Your rating will attribute to something rotten Tomatoes Audience Score. There is a brand babu photos, according to brands only help the. Adds Desktop top googletag. Using a smart coffee scale being the easiest way to guarantee a medicine cup of coffee, who despises film actors, Rahul Ramakrishna play supporting roles. Sumanth Shailendra has a problem of disliking unbranded items. It with an interesting story is by hrithik roshan is not branded things are anthologies suitable for release date of. Happy Republic Day 2021 Amitabh Bachchan Akshay Kumar. He has a release date of control with premium materials. Help us delete comments that drug not taste these guidelines. Republic Day wishes to fans. The gallant action star the junior commissioned officer resulted in a positive response which overwhelmed the enemy by surprise. -

Issaq Full Movie Hindi Dubbed Download

Issaq Full Movie Hindi Dubbed Download Issaq Full Movie Hindi Dubbed Download 1 / 2 Issaq (2013) cast and crew credits, including actors, actresses, directors, writers and more.. Jan 15, 2015 - 59 minKeywords: Issaq Full Movie Issaq Full Movie english subtitles Issaq trailer review ... Full Movie .... Oct 16, 2017 - 70 min - Uploaded by Mehedi HassanIssaq Full Movie Prateik Babbar, Amyra Dastur, Ravi Kishan HD 1080pvia torchbrowser com .... Oct 26, 2013 ... Issaq Full Movie (2013) Watch Online in HD Print Quality Download,Watch Online Issaq ... Savita Damodar Paranjape 2018 Hindi Full Movie.. GET A FREE MONTH. SIGN IN. Issaq: A Netflix Original. Issaq. 2013 TV-MA 2h 19m. Two young lovers in Banaras are caught in the ... International Movies, Indian Movies, Musicals, Bollywood Movies, Romantic ... Available to download.. Watch Hindi Movies Online with HD Quality in 1080P. ... Travel through time and explore the wide range of movies that YuppFlix has lined up for .... Issaq 2013 4.. 11 Abr 2018 ... issaq movie hindi. Elysium (2013) 720p BluRay 800MB 720p Movies Download mkv Movies . full hd 1080p hollywood movies free download, .... Ishq (1997) Hindi Full Screen HD 720p Movie - Ajay Devgan,Aamir Khan,Kajol,Juhi Chawla By Entertainment Counter Download .... May 30, 2018 ... Issaq Movie Hindi Dubbed Torrent - DOWNLOAD. 92908340b8 Acrimony (2018) Full MOVIE FREE DOWNLOAD HINDI DUBBED TORRENT .... Issaq Full Movie Prateik Babbar, Amyra Dastur, Ravi Kishan HD 1080pvia torchbrowser com. thumb. Mera Faisla (2016) Full Hindi Dubbed Movie | Surabhi .... Find Issaq (Hindi Movie / Bollywood Film / Indian Cinema DVD) at Amazon.com ... Dolby, Subtitled, NTSC; Language: Hindi; Subtitles: English; Dubbed: Hindi .... Issaq (2013).