Constructing Social Bandits: the Saga of Sontag and Evans, 1889-1911

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promise Beheld 119

Promise Beheld 119 Mescalero Apache wicki-up (Courtesy Guadelupe Mountain National Park) Indian mortar holes at Guadalupe Mountains National Park (Courtesy Guadelupe Mountain National Park) 120 Promise Beheld Historical sketch of El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak in 1854, drawn by Robert Schuchard (Courtesy Guadelupe Mountain National Park) El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak (Courtesy National Park Service) Promise Beheld 121 During the 1880s and 1990s many of the ranchers of the rugged Guadalupes continued to drive their cattle several hundred miles northeast to Clayton, N.M., because it had a more direct rail route to their markets. The men who made that trail drive in 1889 sat for this portrait in Clayton, surrounding a clerk from a Clayton general store who asked if he could join them for the picture. “Black Jack” Ketchem, who was hanged at Clayton in 1901 for train robbery was a Guadalupe cowboy and a member of this trail drive. He stands at the center, rear. (Courtesy Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society of Carlsbad) The Butterfield Stage line ran past the Guadalupe mountains, and the Pinery, one of its way stations, was located at the base of Guadalupe Peak. All that is left today at the national park are these ruins. (Courtesy Guadalupe Mountains National Park) 122 Promise Beheld The town of Eddy (today’s Carlsbad) was a real estate development created “overnight” on a previously structureless and treeless plain. The town company immediately paid for the creation of several major buildings to impress potential buyers. This photograph shows the Haggerman Hotel and the brick bank building to the right. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

1810 1830 1820 1850 the Plains 1840 1860 the Horse the Buffalo

GCSE History Knowledge Organiser: The Plains & The Sioux Indians roam freely on the Plains Limited violence between settlers & Indians 1810 1820 1824 Bureau of Indian Affairs 1830 1840 1850 1860 Indian hunting grounds 1830 Indian 1851 Indian Removal Act Appropriations Act The Plains The Buffalo Society Warfare Before a hunt, the Women were highly valued as they created the future of Indian warriors carried out Sioux would stage a the band. Children didn’t go to school but learned skills raids to seek revenge, or steal Buffalo Dance. Here, from extended family. The survival of the band was more horses. It usually only they would important than any individual. happened in summer. Scalping communicate with was a common practice. Wakan Tanka to ask Most marriages took place for love. Men went to live with for a good hunt. his wife’s family. Rich men were allowed to have more than Warriors believed that without Warrior Societies one wife. This was because there were usually more your whole body, you couldn’t would plan the hunts women than men, and polygamy ensured the future of the go to the Happy Hunting so as not to scare the band. Ground so scalping became a buffalo. Two or three At least once a year, all bands would meet as a nation. trophy so your enemy wouldn’t The Plains were desert-land – a mix of grass and flowing rivers hunts a year were Chiefs achieved their power through prestige and bravery. meet you there. They also with the Black Hills, heavily wooded, in the North. -

Oklahoma Territory Inventory

Shirley Papers 180 Research Materials, General Reference, Oklahoma Territory Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials General Reference Oklahoma Territory 251 1 West of Hell’s Fringe 2 Oklahoma 3 Foreword 4 Bugles and Carbines 5 The Crack of a Gun – A Great State is Born 6-8 Crack of a Gun 252 1-2 Crack of a Gun 3 Provisional Government, Guthrie 4 Hell’s Fringe 5 “Sooners” and “Soonerism” – A Bloody Land 6 US Marshals in Oklahoma (1889-1892) 7 Deputies under Colonel William C. Jones and Richard L. walker, US marshals for judicial district of Kansas at Wichita (1889-1890) 8 Payne, Ransom (deputy marshal) 9 Federal marshal activity (Lurty Administration: May 1890 – August 1890) 10 Grimes, William C. (US Marshal, OT – August 1890-May 1893) 11 Federal marshal activity (Grimes Administration: August 1890 – May 1893) 253 1 Cleaver, Harvey Milton (deputy US marshal) 2 Thornton, George E. (deputy US marshal) 3 Speed, Horace (US attorney, Oklahoma Territory) 4 Green, Judge Edward B. 5 Administration of Governor George W. Steele (1890-1891) 6 Martin, Robert (first secretary of OT) 7 Administration of Governor Abraham J. Seay (1892-1893) 8 Burford, Judge John H. 9 Oklahoma Territorial Militia (organized in 1890) 10 Judicial history of Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 11 Politics in Oklahoma Territory (1890-1907) 12 Guthrie 13 Logan County, Oklahoma Territory 254 1 Logan County criminal cases 2 Dyer, Colonel D.B. (first mayor of Guthrie) 3 Settlement of Guthrie and provisional government 1889 4 Land and lot contests 5 City government (after -

Payment of Taxes As a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: a Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 9 | Number 1 Article 13 1-1-1969 Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q. Mix Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Averill Q. Mix, Comment, Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism, 9 Santa Clara Lawyer 244 (1969). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol9/iss1/13 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PAYMENT OF TAXES AS A CONDITION OF TITLE BY ADVERSE POSSESSION: A NINETEENTH CENTURY ANACHRONISM In California the basic statute governing the obtaining of title to land by adverse possession is section 325 of the Code of Civil Procedure.' This statute places California with the small minority of states that unconditionally require payment of taxes as a pre- requisite to obtaining such title. The logic of this requirement has been under continual attack almost from its inception.2 Some of its defenders state, however, that it serves to give the true owner notice of an attempt to claim his land adversely.' Superficially, the law in California today appears to be well settled, but litigation in which the tax payment requirement is a prominent issue continues to arise. -

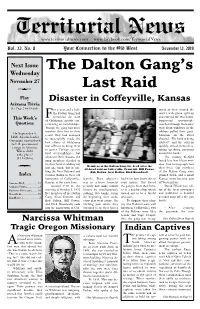

The Dalton Gang's Last Raid

Territorial News www.territorialnews.com www.facebook.com/TerritorialNews Vol. 33, No. 8 Your Connection to the Old West November 13, 2019 Next Issue The Dalton Gang’s Wednesday November 27 Last Raid Play Disaster in Coffeyville, Kansas Arizona Trivia See Page 2 for Details or a year and a half, nized as they crossed the the Dalton Gang had town’s wide plaza, split up This Week’s Fterrorized the state and entered the two banks. of Oklahoma, mostly con- Suspicious townspeople Question: centrating on train holdups. watched through the banks’ Though the gang had more wide front windows as the murders than loot to their robbers pulled their guns. On September 4, credit, they had managed Someone on the street 1886, Apache leader to successfully evade the shouted, “The bank is being Geronimo surrendered to U.S. government best efforts of Oklahoma robbed!” and the citizens troops in Arizona. law officers to bring them quickly armed themselves, Where did it to justice. Perhaps success taking up firing positions take place? bred overconfidence, but around the banks. (14 Letters) whatever their reasons, the The ensuing firefight gang members decided to lasted less than fifteen min- try their hand at robbing not utes. Four townspeople lost Members of the Dalton Gang lay dead after the just one bank, but at rob- ill-fated raid on Coffeyville. From left: Bill Power, their lives, four members bing the First National and Bob Dalton, Grat Dalton, Dick Broadwell. of the Dalton Gang were Index Condon Banks in their old gunned down, and a small hometown of Coffeyville,, feyville. -

Dalton Brothers Wore the White Hats." Real West, July 1981, P

Revised 3/1/12 Dalton Gang Western magazine articles $4.00 per issue To order magazines, go to our website http://www.magazinehouse.us/ Boessenecker, John. "Grat Dalton's California Jailbreak." Real West, Aug. 1988, p. 14. Brant, Marley. "Outlaws' Inlaws in California." Frontier Times, Feb. 1985, p. 18. Chesney, W.D. "I Saw the Daltons Die." Real West, May 1964, p. 18. DeMattos, Jack. "The Daltons" ("Gunfighters of the Real West"). Real West, Dec. 1983, p. 32. Hane, Louis. "Bloodbath at Coffeyville." Westerner, Jan.-Feb. 1972, p. 34. McClelland, Marshall K. "The Day the Daltons Died." Badman, Fall 1972, p. 32. Noren, William. "The Daltons Were Our Neighbors in California." True West, Sept. 1983, p. 29. O'Neal, Harold. "The San Joaquin Train Holdups." Golden West, Mar. 1966, p. 44. Preece, Harold. "Grat Dalton's Fatal Looking Glass." The West, Dec. 1964, p. 14. Preece, Harold. "The Day the Daltons Died." Frontier West, Apr. 1971, p. 10. Rozar, Lily-B. "Inside the Dalton Legend." The West, Aug. 1972, p. 32. Smith, Robert Barr. "Dalton Gang's Mystery Rider at Coffeyville." Wild West, Oct. 1995, p.64. Walker, Wayne T. "When the Dalton Brothers Wore the White Hats." Real West, July 1981, p. 32. *Whittlesey, D.H. "He Said 'Hell No' to the Daltons." Golden West, May 1974, p. 38. Dalton, Emmett Charbo, Eileen. "Doc Outland and Emmett Dalton." True West, Aug. 1980, p. 43. Dalton, Emmett. "Prison Delivery." Old West, Spring 1971, p. 74. Martin, Chuck. "Emmett Dalton's Six-Shooter." Badman, Fall 1972, p. 34. Preece, Harold. "The Truth About Emmett Dalton." Real West, Mar. -

Prince George's Counfy Historical Society News Andnotes

rrl PrinceGeorge's Counfy zU a HistoricalSociety News andNotes Prince Georgeansin the Old West By Alan Virta When I told my friends and colleaguesin Idaho that I was going to talk about Prince Georgeansin the Old West-they gave me funny looks and more than one askedme- How could I ever find them? How would I know who they were? Well, finding them was the leastof myproblems-because everywhereI think I've ever gone-in the United States,at least-l'vs found tracesof PrinceGeorgeans. In the ancientcemetery in the village of Roseville,Ohio-home of my grandparents, greatgrandparents, and two generationsbefore them-there is a huge gravestonewith the name"Grafton Duvall" carvedon it, as PrinceGeorge's a-soundingname as everthere couldbe. When I checkedHany Wright Newman'sbible of Duvall genealogyI found that this GraftonDuvall-one of a numberof men to bearthat nameover several generations-wasindeed a nativeof PrinceGeorge's County. When I moved to Mississippi,one of the first placesI went to visit was Natchez-for nearthere is a historical marker denotingthe site of what was known as the "Maryland Colony" early settlementof PrinceGeorgeans from the Aquascoarea who movedto the old Southwestin the early yearsof the 1800sto take advantageof the fertile soil and opportunitiesthere. PrinceGeorgeans have been heading West sincethe very beginning. PrinceGeorgeans were,indeed, some of the first Westerners-becausein the late 17thcentury, this unorganized,lightly-settled land betweenthe Patuxentand Potomac Rivers was the West. It was Maryland's frontier,where European settlement bumped up againstthe original Indianinhabitants. Stories of Indian raids on the AnacostiaRiver settlements;of Ninan Beall's Rangersw\o patrolledthe frontier line beyondthe river-are as dramaticas any storiesfrom the 19tncentury West of the Apacheand the Sioux. -

The Story Kings County California

THE STORY OF KINGS COUNTY CALIFORNIA By J. L. BROWN Printed by LEDERER, STREET & ZEUS COMPANY, INC. BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA In cooperation with the ART PRINT SHOP HANFORD, CALIFORNIA S?M£Y H(STORV LIBRARY 35 NORTH WE<" THE STORY OF KINGS COUNTY TABLE OF CONTENTS FRONTISPIECE by Ralph Powell FOREWORD Chapter I. THE LAND AND THE FIRST PEOPLE . 7 Chapter II. EXPLORERS, TRAILS, AND OLD ROADS 30 Chapter III. COMMUNITIES 43 Chapter IV. KINGS AS A COUNTY UNIT .... 58 Chapter V. PIONEER LIFE IN KINGS COUNTY 68 Chapter VI. THE MARCH OF INDUSTRY .... 78 Chapter VII. THE RAILROADS AND THE MUSSEL SLOUGH TROUBLE 87 Chapter VIII. THE STORY OF TULARE LAKE 94 Chapter IX. CULTURAL FORCES . 109 Chapter X. NATIONAL ELEMENTS IN KINGS COUNTY'S POPULATION 118 COPYRIGHT 1941 By J. L. BROWN HANFORD, CALIFORNIA FOREWORD Early in 1936 Mrs. Harriet Davids, Kings County Li brarian, and Mr. Bethel Mellor, Deputy Superintendent of Schools, called attention to the need of a history of Kings County for use in the schools and investigated the feasibility of having one written. I had the honor of being asked to prepare a text to be used in the intermediate grades, and the resulting pamphlet was published in the fall of that year. Even before its publication I was aware of its inadequacy and immediately began gathering material for a better work. The present volume is the result. While it is designed to fit the needs of schools, it is hoped that it may not be found so "textbookish" as to disturb anyone who may be interested in a concise and organized story of the county's past. -

Social Banditry and Nation-Making: the Myth of A

SOCIAL BANDITRYAND NATION-MAKING: THE MYTH OF A LITHUANIAN ROBBER* I SOCIAL BANDITRY AND NATION-BUILDING On 22 April 1877, at the St George’s Day market, a group of men gotintoafightinalocalinnatLuoke_,asmalltowninnorth-western Lithuania. Soon the brawl spilled into the town’s market square. After their arrival, the Russian police discovered that what had started as a scuffle had turned into a bloody samosud (literally, self-adjudication), in which a mob of several hundred men and women took the law into its own hands. The victim of the mob violence lay dead on the square with a broken skull. According to a police report, he was ‘the greatest robber and horse thief of the neighbouringdistricts’, alocalpeasantcalledTadasBlinda.1 Asan outlaw, Blinda was buried together with suicides ‘beyond a ditch’ in an unconsecrated corner of the cemetery in Luoke_.2 Today in Lithuania Blinda is largely remembered as a popular legendary hero, ‘a leveller of the world’, who would take from the rich and give to the poor. He is a national and cultural icon whose name is found everywhere: in legends, folk songs, politics, films, cartoons, tourist guides, beer advertising, pop music, and so on. This article, therefore, begins with a puzzle: how did this peasant, who was killed by the mob, become ‘the Lithuanian Robin Hood’, a legendary figure whose heroic deeds are inscribed deep in con- temporary Lithuanian culture? In Primitive Rebels (1959) and Bandits (1969), Eric Hobsbawm proposed a comparative model of social banditry that included colourful figures such as the English Robin Hood, the Polish– Slovak Juro Ja´nosˇ´ık, the Russians Emelian Pugachev and Stenka * I am very grateful to Peter Gatrell and Stephen Rigby for their generous comments on this text, and for references and corrections. -

Peasants “On the Run”: State Control, Fugitives, Social and Geographic Mobility in Imperial Russia, 1649-1796

PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Washington, DC May 7, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrey Gornostaev All Rights Reserved ii PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Thesis Advisers: James Collins, Ph.D. and Catherine Evtuhov, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the issue of fugitive peasants by focusing primarily on the Volga-Urals region of Russia and situating it within the broader imperial population policy between 1649 and 1796. In the Law Code of 1649, Russia definitively bound peasants of all ranks to their official places of residence to facilitate tax collection and provide a workforce for the nobility serving in the army. In the ensuing century and a half, the government introduced new censuses, internal passports, and monetary fines; dispatched investigative commissions; and coerced provincial authorities and residents into surveilling and policing outsiders. Despite these legislative measures and enforcement mechanisms, many thousands of peasants left their localities in search of jobs, opportunities, and places to settle. While many fugitives toiled as barge haulers, factory workers, and agriculturalists, some turned to brigandage and river piracy. Others employed deception or forged passports to concoct fictitious identities, register themselves in villages and towns, and negotiate their status within the existing social structure. -

Banditry and Revolution in the Mexican Bajio, 1910-1920

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 1997 The infernal rage: banditry and revolution in the Mexican Bajio, 1910-1920 Frazer, Christopher Brent Frazer, C. B. (1997). The infernal rage: banditry and revolution in the Mexican Bajio, 1910-1920 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/18590 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/26601 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca TEE UNNERSITY OF CALGARY The Memal Rage: Banditry and Revolution in the Mexican Bajio, 1910-1920 by Christopher Brent Frazer A THESIS SUBMIï'TED TO THE FACWOF GRADUATE STUDES IN PARTLAI, FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS CALGARY,ALBERTA NNE,1997 Q Christopher Brent Frazer 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 ,,,da du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie SeMces seMces bibliographiques 395 Weiiington Street 395, nre Wellinw OtEawaON KIAON4 --ON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence aiiowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats.