Institutions in Myanmar's 2015 Election: Election Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Monitor No.31

Euro-Burma Office 14 – 20 September 2013 Political Monitor 2013 POLITICAL MONITOR NO.31 OFFICIAL MEDIA PRESIDENT THEIN SEIN MEETS 88 GENERATION PEACE AND OPEN SOCIETY GROUP President Thein Sein held talks with the 88 Generation Peace and Open Society Group led by Min Ko Naing on 14 September. They held cordial discussions covered a wide range of issues including reconciliation, mapping of a new form of political culture, flourishing of democratic practices and promoting socio-economic status of the people and to work together in dealing with transitional challenges. Others issues included resolving land disputes, political prisoners and all inclusiveness of national races groups, political parties and Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in the on-going peace process.1 CSOs, MEDIA PLAY CRUCIAL ROLE FOR FREE, FAIR ELECTIONS A media conference (2013) between the Union Election Commission and political parties, jointly organized by Myanmar Multiparty Democracy Programme and International Media Support (IMS), was held in Yangon on 14 September. In his speech, the Union Election Commission (UEC) Chairman Tin Aye said that a strategic plan is being drawn in cooperation to the holding of free and fair elections in 2015. Laws and bylaws which are being drafted and cooperation of all political parties is of prime importance for successful holding the elections. Tin Aye highlighted the crucial role of CSOs and media in ensuring a free and fair election and also called for the collaboration of all political parties, CSOs and media in the holding of elections.2 LAWMAKERS MEET TO PROTECT RIGHTS OF ETHNIC NATIONALITIES Hluttaw Speakers and officials met with Myanmar Parliamentarian Committee and Union Attorney- General and region/state advocates-general on 13 September to discuss the bill on protection of the rights of ethnic nationalities to cooperate in equalizing the different laws of Regions and States in legislative matters of the Union. -

Burma Briefing

Burma Burma’s 2015 Elections and the Briefing 2008 Constitution No. 41 October 2015 Introduction After the election, regardless of No. 1 Elections due on 8th November are obviously who wins: July 2010 significant, but they are unlikely to be the major turning point in a transition to democracy that • Military appoint Home Affairs Minister, many hope for or have talked them up to be. controlling police, security services and Rather, they will be another step in the military’s much of the justice system. So there could carefully planned transition from direct military rule still be political prisoners. and pariah status to a hybrid military and civilian government which is accepted by the international • Military are not under government or community and sections of Burmese society. Parliamentary control, so they could continue attacks in ethnic states, and use Burma’s 2008 Constitution is designed to present of rape as a weapon of war. the appearance of democracy, while maintaining ultimate military control. It is also specifically • 25% of seats in Parliament reserved for designed for the eventuality of the National League the military ensures a military veto over for Democracy (NLD) winning elections and forming constitutional democratic reforms. a government, without this being a threat to military control. They were not prepared, however, to risk • Military dominated National Defense having Aung San Suu Kyi, the most popular and and Security Council more powerful than influential politician in Burma, head that government. parliament or government. Clauses were put in the Constitution to prevent this. • Military have constitutional right to retake A government which is predominantly made up direct control of government. -

Political Monitor No.21

Euro-Burma Office 6 - 12 September 2014 Political Monitor 2014 POLITICAL MONITOR NO. 21 OFFICIAL MEDIA ELECTION COMMISSION POSTPONES BY-ELECTIONS Union Election Commission Chairman Tin Aye announced in a meeting with political parties on 7 September that the by-elections to be held later this year would be cancelled citing concerns over costs and chairing ASEAN as reasons for the decision. Chairman Tin Aye explained that the Union Election Commission had initially told a parliamentary session on 20 May that the second by- elections would be held in late November or early December. However, now that the parliament is occupied with addressing constitutional and electoral reforms issues, holding by-elections would be burdensome on the political parties, some of whose representatives are members of the committees and commissions tasked with constitutional and electoral amendments. Tin Aye said that the government would have to spend over 2 billion kyats on two elections and, as a result, a second thought should be given to holding the elections as there is no telling whether the spending would benefit the country.1 PRESIDENT MAKES OFFICIAL VISIT TO SWITZERLAND President Thein Sein arrived in Switzerland on 4 September and held talks with Swiss President Didier Burkhalter and discussed a wide range of matters including improvement of vocational training schools, development of agriculture and livestock breeding sectors, capacity building for service personnel and local authorities, peace-making process, human rights promotion, constitutional affairs and holding of free and fair elections. They also exchanged views on peace and stability and the development of Rakhine State, as well as racial and religious conflict prevention and relations between ASEAN and regional countries. -

A Study of Myanmar-US Relations

INDEX A strike at Hi-Mo factory and, 146, “A Study of Myanmar-US Relations”, 147 294 All Burma Students’ Democratic abortion, 318, 319 Front, 113, 125, 130 n.6 accountability, 5, 76 All India Radio, 94, 95, 96, 99 financial management and, 167 All Mon Regional Democracy Party, administrative divisions of Myanmar, 104, 254 n.4 170, 176 n.12 allowances for workers, 140–41, 321 Africa, 261 American Centre, 118 African National Congress, 253 n.2 American Jewish World Service, 131 Agarwal, B., 308 n.7 “agency” of individuals, 307 Amyotha Hluttaw (upper house of Agricultural Census of Myanmar parliament), 46, 243, 251 (1993), 307 Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom Agricultural Ministers in States and League, 23 Regions, 171 Anwar, Mohammed, 343 n.1 agriculture, 190ff ANZ Bank (Australia), 188 loans for, 84 “Arab Spring”, 28, 29, 138 organizational framework of, “arbitrator [regime]”, 277 192, 193 Armed Forces Day 2012, 270 Ah-Yee-Taung, 309 armed forces (of Myanmar), 22, 23, aid, 295, 315 262, 269, 277, 333, 334 donors and, 127, 128 battalions 437 and 348, 288 Kachin people and, 293, 295 border areas and, 24 Alagappa, Muthiah, 261, 263, 264 constitution and, 16, 20, 24, 63, Albert Einstein Institution, 131 n.7 211, 265, 266 All Burma Federation of Student corruption and, 26, 139–40 Unions, 115, 121–22, 130 n.4, 130 disengagement from politics, 259 n.6, 148 expenditure, 62, 161, 165, 166 “fifth estate”, 270 356 Index “four cuts” strategy, 288, 293 Aung Kyaw Hla, 301 n.5 impunity and, 212, 290 Aung Ko, 60 Kachin State and, 165, 288, 293 Aung Min, 34, -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

Direction Relating to Foreign Currency Transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) As Amended Made Under Regulation 5 of The

Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) as amended made under regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959 This compilation was prepared on 22 October 2008 taking into account amendments up to Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma – Amendment to the Annex and Variation of Exemptions – Amendment to the Annexes (16/10/2008) Prepared by the Office of Legislative Drafting and Publishing, Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra Federal Register of Legislative Instruments F2008C00574 2 Direction relating to foreign currency transactions and to Burma (18/10/2007) The Reserve Bank of Australia, pursuant to regulation 5 of the Banking (Foreign Exchange) Regulations 1959, hereby directs that: 1. a person must not, either on the person’s own behalf or on behalf of another person, buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency in Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way in Australia; 2. a resident, or a person acting on behalf of a resident, must not buy, borrow, sell, lend or exchange foreign currency outside Australia, or otherwise deal with foreign currency in any other way outside Australia; 3. a person must not be a party to a transaction, being a transaction that takes place in whole or in part in Australia or to which a resident is a party, that has the effect of, or involves, a purchase, borrowing, sale, loan or exchange of foreign currency, or otherwise relates to foreign currency where the transaction relates to property, securities or funds owned or controlled directly or indirectly by, or otherwise relates to payments directly or indirectly to, or for the benefit of any person listed in the Annex to this direction. -

Political Monitor No.17

Euro-Burma Office 14 to 20 May 2011 Political Monitor POLITICAL MONITOR NO. 17 GOVERNMENT REDUCES SENTENCES OF PRISONERS BY ONE YEAR President Thein Sein on 16 May 2011 signed Order No.28/2011 granting amnesty to those currently serving prison sentences. Under the Presidential order, those serving death sentences will have their prison terms commuted to life while others will have their sentences commuted by one year exclusive of remission days.1 FOREIGN AFFAIRS MINISTER RECEIVES GERMAN DELEGATION Minister for Foreign Affairs U Wunna Maung Lwin received a Delegation from Germany led by Michael Glos, Member of Parliament of the Federal Democratic Party (FDP) and Dr H. C. Mult Hans Zehetmair, Chairman of Hans Seidel Foundation, at his office on 16 May. The meeting focused on strengthening bilateral ties and cooperation between the two countries.2 Prior to 1988, Germany provided technical cooperation programmes under the state-run German Technical Corporation Agency (GTZ). In 1985, a joint venture agreement to form the Myanmar Fritz Werner Industries Co. Ltd was signed. Under this agreement, German experts were dispatched to Burma to assist the Burmese in the production of small arms at the Defence Services Products Factory (Kapasa) in Yangon. PYITHU HLUTTAW SPEAKER RECEIVES VICE-CHAIRMAN OF CHINESE CENTRAL MILITARY COMMISSION The Speaker of the Pyithu Hluttaw (People’s Parliament) Thura U Shwe Mann received a visiting Chinese delegation led by Vice-Chairman General Xu Caihou of the Central Military Commission at the Zabuthiri Meeting Hall on 14 May. Also present were Deputy Pyithu Hluttaw Speaker U Nanda Kyaw Swar, Pyithu Hluttaw Representatives U Thein Zaw, U Soe Tha, U Maung Maung Thein, Thura U Aye Myint, U Thein Swe, U Soe Naing, U Thurein Zaw, U Win Sein, Col Htay Naing and Colonel Tint Hsan, Maj-Gen Maung Maung Ohn of the Ministry of Defence, Burma’s Military Attaché to China and the Deputy Director- General of the Hluttaw Office. -

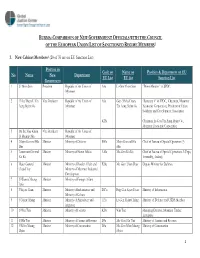

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

EU Official Journal

Official Journal L 99 I of the European Union Volume 64 English edition Legislation 22 March 2021 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/478 of 22 March 2021 implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1998 concerning restrictive measures against serious human rights violations and abuses . 1 ★ Council Regulation (EU) 2021/479 of 22 March 2021 amending Regulation (EU) No 401/2013 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Myanmar/Burma . 13 ★ Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2021/480 of 22 March 2021 implementing Regulation (EU) No 401/2013 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Myanmar/Burma . 15 DECISIONS ★ Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/481 of 22 March 2021 amending Decision (CFSP) 2020/1999 concerning restrictive measures against serious human rights violations and abuses . 25 ★ Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/482 of 22 March 2021 amending Decision 2013/184/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Myanmar/Burma . 37 ★ Council Decision (CFSP) 2021/483 of 22 March 2021 amending Decision 2013/184/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Myanmar/Burma . 40 Acts whose titles are printed in light type are those relating to day-to-day management of agricultural matters, and are generally valid for a limited period. EN The titles of all other acts are printed in bold type and preceded by an asterisk. 22.3.2021 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 99 I/1 II (Non-legislative acts) REGULATIONS COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/478 of 22 March 2021 implementing Regulation -

2021/480 of 22 March 2021 Implementing Regulation (EU) No 401/2013 Concerning Restrictive Measures in Respect of Myanmar/Burma

22.3.2021 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 99 I/15 COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2021/480 of 22 March 2021 implementing Regulation (EU) No 401/2013 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Myanmar/Burma THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EU) No 401/2013 of 2 May 2013 concerning restrictive measures in respect of Myanmar/Burma and repealing Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 (1), and in particular Article 4i thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 2 May 2013, the Council adopted Regulation (EU) No 401/2013. (2) On 22 February 2021, the Council adopted conclusions in which it condemned in the strongest terms the military coup carried out in Myanmar/Burma on 1 February 2021. It called for de-escalation of the crisis through an immediate end to the state of emergency, the restoration of the legitimate civilian government and the opening of the newly elected parliament. (3) The Council also called upon the military authorities to release the President, the State Counsellor and all those who have been detained or arrested in connection with the coup. The Council insisted that unimpeded telecommu nications must be ensured, freedoms of expression, association, and assembly, and access to information guaranteed, and the rule of law and human rights respected. It condemned the military and police repression against peaceful demonstrators while calling for maximum restraint to be exercised by the authorities and for all sides to refrain from violence, in line with international law. -

COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 Amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP Renewing Restrictive Measures Against Burma/Myanmar

L 210/38 EN Official Journal of the European Union 14.8.2009 III (Acts adopted under the EU Treaty) ACTS ADOPTED UNDER TITLE V OF THE EU TREATY COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2009/615/CFSP of 13 August 2009 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (5) Moreover, the Council considers it necessary to amend the lists of persons and entities subject to the restrictive Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in measures in order to extend the assets freeze to enter particular Article 15 thereof, prises that are owned or controlled by members of the regime in Burma/Myanmar or by persons or entities associated with them, Whereas: HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (1) On 27 April 2006, the Council adopted Common Article 1 Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar ( 1). Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP shall be replaced by the texts of Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (2) Council Common Position 2009/351/CFSP ( 2) of 27 April 2009 extended until 30 April 2010 the Article 2 restrictive measures imposed by Common Position 2006/318/CFSP. This Common Position shall take effect on the date of its adoption. (3) On 11 August 2009, the European Union condemned Article 3 the verdict against Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and This Common Position shall be published in the Official Journal announced that it will respond with additional targeted of the European Union. restrictive measures.