Download Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

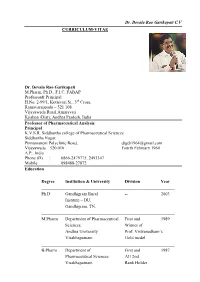

Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati C.V CURRICULUM-VITAE Dr. Devala

Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati C.V CURRICULUM-VITAE Dr. Devala Rao Garikapati M.Pharm, Ph.D., F.I.C. FABAP Professor& Principal H.No. 2-99/1, Kottevari St., 3rd Cross, Ramavarappadu – 521 108 Vijayawada Rural,Amaravati Krishna (Dist), Andhra Pradesh, India Professor of Pharmaceutical Analysis Principal K.V.S.R. Siddhartha college of Pharmaceutical Sciences Siddhartha Nagar, Pinnamaneni Polyclinic Road, [email protected] Vijayawada – 520 010 Fourth February 1964 A.P., India Phone (D) : 0866-2479775, 2493347 Mobile : 098488-27872 Education _____________________________________________________________ Degree Institution & University Division Year _____________________________________________________________ Ph.D Gandhigram Rural -- 2003 Institute – DU, Gandhigram, TN. _____________________________________________________________ M.Pharm Department of Pharmaceutical First and 1989 Sciences, Winner of Andhra University Prof. Viswanadham’s Visakhapatnam Gold medal _____________________________________________________________ B.Pharm Department of First and 1987 Pharmaceutical Sciences AU 2nd Visakhapatnam Rank Holder _____________________________________________________________ F.I.C. Institute of Chemists (India), -- 2005 Kolkata _____________________________________________________________ FABAP Association of Biotechnology -- 2007 And Pharmacy, ANU _____________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ Academic Experience: December 2004 to till date Professor & Principal, -

L,L Ll an EARLY UPANISADIC RE,ADER

AN EARLY UPANISADIC RE,ADER With notes, glossary, and an appendix of related Vedic texts Editedfor the useof Sanskritstudents asa supplementto Lanman'sSariskr it Reader HaNs Flrrunrcn Hocr l l, l i ll MOTILAL BANARSIDASSPUBLISHERS PRIVATE LIMITED . DELHI First Edition : DeLhi 2007 Contents Preface lx Introduction 1 O by Hansllenrich I tock The Texts 25 I: The mystical significanceof the sacrificialhorse (BAU (M) 1:1) 27 ISBN:8l-208 3213,2 (llB) II: A creationmyth associatedwith the agnicayanaand a6vamedha ISBN:81-208321+0 (PB) (from BAU (M) 1:2) 28 III: 'Lead me from untruth(or non-being)to truth(or being) ...' (fromBAU (M) 1:3) 29 MOTILAI, BANARSIDASS IV: Anothercreation myth: The underlying oneness (BAU (M) 1:4) 29 4l U.A. Btrngalow Road, Jawahar Nagar, Dclhi t i0 007 V: A brahminturns to a ksatriyaas teacher, and the parable of Mahalami 8 Chmber, 22 Bhulabhai Desi Road, lvlumbai 400 02ii the sleepingman (from BAU (M) 2:l) 203 Royapetrah High Road, N{ylapore, Chennai 600 004 33 236, 9th N{ain III Block,Jayanagar, Bangalore 560 0l I VI: Yajnavalkyaand Maitreyi (BAU (M) 2:a) J+ Sanas Plaza, 1302 Baji Rao Road, pune 4l I 002 8 Camac Street, Kolkara 700 0 I 7 VII: Ydjffavalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,1: Ashok Rajparh, Patna 800 004 The cows andthe hotr A6vala(BAU (M) 3:l) 36 Chowk, Varanasi 221 001 VIII: Yajfravalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,2: Releasefrom "re-death"(BAU (M) 3:3) 38 IX Ydjfravalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,3: VacaknaviGargi challengesYajfravalkya (BAU (M) 3:8) 39 X: Yajiiavalkya'sdisputations at the assemblyof King Janaka,4: Afr ifr, and VidagdhaSakalya's head flies apart(from BAU (M) 3:9) 40 XI: The beginningof Svetaketu'sinstruction in the transcendental unity of everything(from ChU 6:1-2) 42 XII: The parablesof the fig treeand of the salt,and ilr"trTR (ChU 6:12and 13) +J XIII: The significanceof 3:r (ChU 1:1 with parallelsfrom the Jaiminiya-, , Jaiminiya-Upanisad-,and Aitareya-Brahmanas,and from the Taittiriya- Aranyaka) 44 l. -

Immortal Buddhas and Their Indestructible Embodiments – the Advent of the Concept of Vajrakāya

JIABS Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Volume 34 Number 1–2 2011 (2012) 22011_34_JIABS_GESAMT.indb011_34_JIABS_GESAMT.indb a 111.04.20131.04.2013 009:11:429:11:42 The Journal of the International EDITORIAL BOARD Association of Buddhist Studies (ISSN 0193-600XX) is the organ of the International Association of Buddhist KELLNER Birgit Studies, Inc. As a peer-reviewed journal, KRASSER Helmut it welcomes scholarly contributions Joint Editors pertaining to all facets of Buddhist Studies. JIABS is published twice yearly. BUSWELL Robert The JIABS is now available online in open access at http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/ CHEN Jinhua ojs/index.php/jiabs/index. Articles become COLLINS Steven available online for free 60 months after their appearance in print. Current articles COX Collet are not accessible online. Subscribers can GÓMEZ Luis O. choose between receiving new issues in HARRISON Paul print or as PDF. VON HINÜBER Oskar Manuscripts should preferably be sub- JACKSON Roger mitted as e-mail attachments to: [email protected] as one single fi le, JAINI Padmanabh S. complete with footnotes and references, KATSURA Shōry in two diff erent formats: in PDF-format, and in Rich-Text-Format (RTF) or Open- KUO Li-ying Document-Format (created e.g. by Open LOPEZ, Jr. Donald S. O ce). MACDONALD Alexander Address books for review to: SCHERRER-SCHAUB Cristina JIABS Editors, Institut für Kultur- und SEYFORT RUEGG David Geistesgeschichte Asiens, Apostelgasse 23, A-1030 Wien, AUSTRIA SHARF Robert STEINKELLNER Ernst Address subscription -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Contested Past. Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu

<TARGET "ber1" DOCINFO AUTHOR "Michael Bergunder"TITLE "Contested Past"SUBJECT "Historiographia Linguistica 31:1 (2004)"KEYWORDS ""SIZE HEIGHT "240"WIDTH "160"VOFFSET "2"> Contested Past Anti-Brahmanical and Hindu nationalist reconstructions of Indian prehistory* Michael Bergunder Universität Heidelberg 1. Orientalism When Sir William Jones proposed, in his famous third presidential address before the Asiatick Society in 1786, the thesis that the Sanskrit language was related to the classical European languages, Greek and Latin, and indeed to Gothic, Celtic and Persian, this was later received not only as a milestone in the history of linguistics. This newly found linguistic relationship represented at the same time the most important theoretical foundation on which European Orientalists reconstructed a pre-history of South Asia, the main elements of which achieved general recognition in the second half of the 19th century. According to this reconstruction, around the middle of the second millenium BCE, Indo-European tribes who called themselves a¯rya (Aryans) migrated from the north into India where they progressively usurped the indigenous popula- tion and became the new ruling class. In colonial India this so-called “Aryan migration theory” met with an astonishing and diverse reception within the identity-forming discourses of different people groups. The reconstruction of an epoch lying almost three to four thousand years in the past metamorphosed, in the words of Jan Assman, into an ‘internalized past’, that is, through an act of semioticization the Aryan migration was transformed into a ‘hot memory’ in Levi-Strauss’s sense, and thereby into a ‘founding history, i.e. a myth’ (Assman 1992:75–77). -

The Cosmic Teeth. Part

THE COS.AIIC TEETH BY LAWRENCE PARMLY BROWN //. Flame Teeth and the Teeth of the Sun IT' \'ERYWHERE and always fire has been conceived as some- -—-^ thing that consumes, devours or eats hke a hungry animal or human being; and the more or less individualized flames of fire are sometimes viewed as teeth, but more commonly as tongues. In the very ancient Hindu Rig-Veda the god Agni primarily rep- resents ordinary fire, but secondarily the fiery sun; and there it is said that "He crops the dry ground strewn (with grass and wood), like an animal grazing, he with a golden beard, with shining teeth" (Mandala V, Sukta VH, 7; translation of H. H. Wilson, Vol. HI, p. 247), while his light "quickly spreads over the earth, when with his teeth (of flame) he devours his food" {Ih. VH, iii, 4; Wilson's, Vol. IV, p. 36).^ The Mexican goddess of devouring fire is called Chantico ("In- the-house," with reference to her character as divinity of the do- mestic hearth) and also Ouaxolotl ("Split-at-the-top," for the flame divided into two tips) and Tlappalo ("She-of-the-red-butterfly," perhaps from the flame-like flickering of the insect). Her image is described by Duran with open mouth and the prominent teeth of a carnivorous beast ; and she is associated with the dog as a biting animal, according to one account having been transformed into a dog as a punishment for disregarding a prohibition relating to sac- rifices (Seler, J^aticanus B, p. 273; Spence, Gods of Mexico, p. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

Atharva Veda Engl

ATHARVA VEDA CHAPTER 1 thus makes me stay above. He grants ATHARVA VEDA me the divine revelation of the audi- ble sound and makes me stay above. 4. Imbued with the sound current, CHAPTER I (the Saint) draws me up. Imbued with the sound current, (the Saint) draws me inside (me). He grants me Hymn 1 the divine revelation of the audible sound and thus gives me enlighten- Rishi: Atharva ment. Devta: Vachaspati 1. He (the Saint) grants (me) three Hymn 2 categories of eternal divine revela- tions. He unfolds all the divine forms Rishi: Atharva (to me). Imbued with the sound cur- Devta: Prithvi rent, (the Saint) gives (me) strength with the divine revelations. Imbued 1. Residing inside (me), (the Saint) with the sound current, he always gives me the nourishing divine reve- gives me the divine revelations. lations and makes me beatific. He makes the divine revelations flow to 2. Imbued with the sound current, control the devotee. Residing inside, (the Saint) in meditation makes me the Saint is like a mother to the devo- beatific. The wise Saint with the di- tee. He makes the audible sound cur- vine revelations makes me mighty. rent flow to make the devotee beatif- The virtuous Saint grants me the di- ic. vine revelation of the audible sound. He grants me the divine revelation of 2. The living Saint meets me by the audible sound and makes me stay himself. He makes me (the son) be- above. atific. With the ever-flowing divine revelations of sound, he destroys 3. The living Saint grants the devo- (my) evil thinking and malice. -

Upanishad Vahinis

Upanishad Vahini Stream of The Upanishads SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Upanishad Vahini 7 DEAR READER! 8 Preface for this Edition 9 Chapter I. The Upanishads 10 Study the Upanishads for higher spiritual wisdom 10 Develop purity of consciousness, moral awareness, and spiritual discrimination 11 Upanishads are the whisperings of God 11 God is the prophet of the universal spirituality of the Upanishads 13 Chapter II. Isavasya Upanishad 14 The spread of the Vedic wisdom 14 Renunciation is the pathway to liberation 14 Work without the desire for its fruits 15 See the Supreme Self in all beings and all beings in the Self 15 Renunciation leads to self-realization 16 To escape the cycle of birth-death, contemplate on Cosmic Divinity 16 Chapter III. Katha Upanishad 17 Nachiketas seeks everlasting Self-knowledge 17 Yama teaches Nachiketas the Atmic wisdom 18 The highest truth can be realised by all 18 The Atma is beyond the senses 18 Cut the tree of worldly illusion 19 The secret: learn and practise the singular Omkara 20 Chapter IV. Mundaka Upanishad 21 The transcendent and immanent aspects of Supreme Reality 21 Brahman is both the material and the instrumental cause of the world 21 Perform individual duties as well as public service activities 22 Om is the arrow and Brahman the target 22 Brahman is beyond rituals or asceticism 23 Chapter V. Mandukya Upanishad 24 The waking, dream, and sleep states are appearances imposed on the Atma 24 Transcend the mind and senses: Thuriya 24 AUM is the symbol of the Supreme Atmic Principle 24 Brahman is the cause of all causes, never an effect 25 Non-dualism is the Highest Truth 25 Attain the no-mind state with non-attachment and discrimination 26 Transcend all agitations and attachments 26 Cause-effect nexus is delusory ignorance 26 Transcend pulsating consciousness, which is the cause of creation 27 Chapter VI. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I ..............................................................................................................................