Chippenham Parish, Covering Landscape, Settlement and Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HD1650 Trinity Gardens-16Pp Brochure EMAIL

3 new exclusive high quality detached 4 bedroom family homes situated on Hardenhuish Lane PLOT 1 Trinity Gardens is an exclusive private development of just three luxury houses, architect designed to the highest standard and located within the highly desirable area of Hardenhuish, Chippenham. Trinity Gardens is approached via a slip road off Hardenhuish Lane. The houses are constructed in a traditional manner with high quality brickwork and reconstructed stonework to PLOT 3 the external elevations and slates to the roof. Internally the houses have excellent room proportions with crisp, modern design. Trinity Gardens has been designed with strong The accommodation is arranged with open plan kitchen/ breakfast and family room. There is a well proportioned emphasis on the external sitting room with wood burning stove and a study/snug design embodying the on the ground floor. A special feature of all the houses is a separate utility room off the kitchen with doors giving golden ratio rule of access to the front and rear of the houses. classical buildings. Upstairs, the four bedrooms have the benefit of two en-suite bathrooms and a family bathroom. All bedrooms have fitted wardrobes. PLOT 2 Outside there is a double garage with electric opening door and the gardens, front and rear, are laid to grass. Trinity Gardens Hardenhuish Lane Chippenham SN14 6HR Little Waitrose Chippenham Railway Station SUPERB LOCATION Chippenham is a vibrant historic market town situated in the heart of Wiltshire with easy access to Bath, Bristol and Swindon. TRANSPORT Trinity Gardens lies just to the north west of Chippenham town centre with both junction 17 of the M4 motorway and Chippenham mainline railway station less than 5 minutes drive by car. -

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the Differences Between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas

Addendum to School Places Strategy 2017-2022 – Explanation of the differences between Wiltshire Community Areas and Wiltshire School Planning Areas This document should be read in conjunction with the School Places Strategy 2017 – 2022 and provides an explanation of the differences between the Wiltshire Community Areas served by the Area Boards and the School Planning Areas. The Strategy is primarily a school place planning tool which, by necessity, is written from the perspective of the School Planning Areas. A School Planning Area (SPA) is defined as the area(s) served by a Secondary School and therefore includes all primary schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into that secondary school. As these areas can differ from the community areas, this addendum is a reference tool to aid interested parties from the Community Area/Area Board to define which SPA includes the schools covered by their Community Area. It is therefore written from the Community Area standpoint. Amesbury The Amesbury Community Area and Area Board covers Amesbury town and surrounding parishes of Tilshead, Orcheston, Shrewton, Figheldean, Netheravon, Enford, Durrington (including Larkhill), Milston, Bulford, Cholderton, Wilsford & Lake, The Woodfords and Great Durnford. It encompasses the secondary schools The Stonehenge School in Amesbury and Avon Valley College in Durrington and includes primary schools which feed into secondary provision in the Community Areas of Durrington, Lavington and Salisbury. However, the School Planning Area (SPA) is based on the area(s) served by the Secondary Schools and covers schools in the towns and surrounding villages which feed into either The Stonehenge School in Amesbury or Avon Valley College in Durrington. -

Sutton Benger Parish Council

Sutton Benger Parish Housing Needs Survey Survey Report March 2015 Wiltshire Council County Hall, Bythesea Road, Trowbridge BA14 8JN Contents Page Parish summary 3 Introduction 4 Aim 4 Survey distribution and methodology 5 Key findings 5 Part 1 – People living in parish 5 Part 2 – Housing need 9 Affordability 12 Summary 13 Recommendations 14 2 1. Parish Summary The parish of Sutton Benger is in Chippenham Community Area within the local authority area of Wiltshire. • There is a population of 1,057 according to the 2011 Census, comprised of 415 households.1 • The parish of Sutton Benger stretches from the hamlet of Draycot Cerne in the west, through the village of Sutton Benger to the River Avon in the east, and from the Stanton Household Recycling Centre & Chippenham Pit Stop in the north, to the National Trust's sites of Special Scientific Interest and County Wildlife in the south. • The medieval village layout of a High Street and parallel Back Lane (now Chestnut Road) and a staggered cross roads beside the 13th Century Parish Church, All Saints, formed by Seagry Road and Bell Lane is still clearly visible, even with the addition of a large housing estate that doubled the size of the village in the 1970s. A further 25% increase in housing stock (85 homes) is currently being constructed upon the previous 'chicken factory' site. With another 41 houses awaiting planning application decisions, the size of the village is set to increase further. • The village straddles the B4069 (Chippenham to Lyneham road) and is in close proximity to junction 17 of the M4, giving easy access to Swindon, Bath and Bristol, as well as benefitting from the more local amenities either in Chippenham to the south west or Malmesbury in the north. -

Memorials of Old Wiltshire I

M-L Gc 942.3101 D84m 1304191 GENEALOGY COLLECTION I 3 1833 00676 4861 Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2009 with funding from Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center http://www.archive.org/details/memorialsofoldwiOOdryd '^: Memorials OF Old Wiltshire I ^ .MEMORIALS DF OLD WILTSHIRE EDITED BY ALICE DRYDEN Editor of Meinoriah cf Old Northamptonshire ' With many Illustrations 1304191 PREFACE THE Series of the Memorials of the Counties of England is now so well known that a preface seems unnecessary to introduce the contributed papers, which have all been specially written for the book. It only remains for the Editor to gratefully thank the contributors for their most kind and voluntary assistance. Her thanks are also due to Lady Antrobus for kindly lending some blocks from her Guide to Amesbury and Stonekenge, and for allowing the reproduction of some of Miss C. Miles' unique photographs ; and to Mr. Sidney Brakspear, Mr. Britten, and Mr. Witcomb, for the loan of their photographs. Alice Dryden. CONTENTS Page Historic Wiltshire By M. Edwards I Three Notable Houses By J. Alfred Gotch, F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A. Prehistoric Circles By Sir Alexander Muir Mackenzie, Bart. 29 Lacock Abbey .... By the Rev. W. G. Clark- Maxwell, F.S.A. Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers . By H. St. George Gray The Rising in the West, 1655 . The Royal Forests of Wiltshire and Cranborne Chase The Arundells of Wardour Salisbury PoHtics in the Reign of Queen Anne William Beckford of Fonthill Marlborough in Olden Times Malmesbury Literary Associations . Clarendon, the Historian . Salisbury .... CONTENTS Page Some Old Houses By the late Thomas Garner 197 Bradford-on-Avon By Alice Dryden 210 Ancient Barns in Wiltshire By Percy Mundy . -

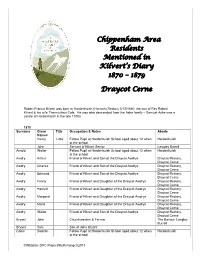

Draycot Cerne

Chippenham Area Residents Mentioned in Kilvert’s Diary 1870 – 1879 Draycot Cerne Robert Francis Kilvert was born at Hardenhuish (Harnish) Rectory 3/12/1840, the son of Rev Robert Kilvert & his wife Thermuthius Cole. He was also descended from the Ashe family – Samuel Ashe was a curate at Hardenhuish in the late 1700s. 1870 Surname Given Title Occupation & Notes Abode Names Henry ‘Little’ Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school John Servant of Kilvert Senior Langley Burrell Arnold Walter Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school Awdry Arthur Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Charles Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Edmund Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Fanny Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Harriett Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Margaret Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Maria Friend of Kilvert and Daughter of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Awdry Walter Friend of Kilvert and Son of the Draycot Awdrys Draycot Rectory, Draycot Cerne Bryant John Churchwarden & Farmer The Barrow, Langley Burrell Bryant Tom Son of John Bryant Coles Deacon Fellow Pupil at Hardenhuish School aged about 12 when Hardenhuish at the school ©Wiltshire -

Wiltshire and Swindon Waste Core Strategy

Wiltshire & Swindon Waste Core Strategy Development Plan Document July 2009 Alaistair Cunningham Celia Carrington Director, Economy and Enterprise Director of Environment and Wiltshire Council Regeneration Bythesea Road Swindon Borough Council County Hall Premier House Trowbridge Station Road Wiltshire Swindon BA14 8JN SN1 1TZ © Wiltshire Council ISBN 978-0-86080-538-0 i Contents Page 1. Introduction 1 2. Key Characteristics of Wiltshire and Swindon 3 3. Waste Management in Wiltshire and Swindon: Issues and Challenges 11 4. Vision and Strategic Objectives 14 5. Strategies, Activities and Actions 18 6. Implementation, Monitoring and Review 28 Appendix 1 Glossary of Terms 35 Appendix 2 Development Control DPD Policy Areas 40 Appendix 3 Waste Local Plan (2005) Saved Policies 42 Appendix 4 Key Diagram 44 ii Executive Summary The Waste Core Strategy for Wiltshire and Swindon sets out the strategic planning policy framework for waste management over the next 20 years. The Waste Core Strategy forms one element of the Wiltshire and Swindon Minerals and Waste Development Framework. In this sense, the Core Strategy should be read in conjunction with national and regional policy as well as local policies –including the emerging Minerals and Waste Development Control Policies Development Plan Document (DPD) and the Waste Site Allocations DPD. The Strategy considers the key characteristics of Wiltshire and Swindon such as population trends, economic performance, landscape importance and cultural heritage. It identifies that approximately 68.6% of the Plan area is designated for its landscape and ecological importance, a key consideration within the Waste Core Strategy. The Strategy gives a summary of the current characteristics of waste management activities in Wiltshire and Swindon. -

Download Bristol Walking

W H II T RR EE E D L H LL A A A N M D D II PP E TT G O S R N O V R RR EE O O W AA OO A D H RR U D BB G RR II B A LL S CC R E M ONO R E H N LL H A E H T H CC H R Y A CHERCH R TT EE RR A S O O O Y EE 4 M AD H LL E N C D II SS TT 1 RTSEY PP E L CC D R K N L 0 T TT A EE S EE O R HA S O G E CC NN 8 K A N C E N N AA E P M IIN A TT Y RD LEY RO B F H D W L II R F S P R PP M R R L RD W Y CC Y II K D A E O EE N R A A D A U R DD O O E U LLLL A AA D RD RR WAVE A H M EN A B P S P RR N O TT D M LL KK V TT A ININ T C D H H H R BB BB DD LA E O N T AD E R NN K S A A A EE A SS S N C A G RO B E AA D T VI M A L S OO A T RR D TT A OA ST RONA U M L B TT NER A OO O O C NN DD R E RR TT AAN TT M R E O B RR JJ CK T H Y EE NN OOH RONA O II N II R G R L O PP T R EE N OO H N O L AA RR A A RR II RR D T LL CH A A A A NSN C A O T RR O OO V T A R D N C SS V KK DD S D E C VV W D O R NSN H EE R R F EE L R O UU A L S IIE L N AD R A L L II N TT R IAL D K R H U OADO A O O ER A D R EE P VE OD RO O TT N AD O A T T IMPERIIM W D CC NE E D S N II A E OA N E L A D V E R F PP A S R E FR N R EY KK V D O O O TL A E UG T R R T HA RR R E ADA G R S W M N S IIN Y D G A A O P LL E AL PP R R S L L D N V Y WE H YN T II IIN DE WE S R L A LLE C A Y N O E T G N K R O F M N RORO II HA D TO R E D P A T E Y II L R L E P L Y E A A M L R E DD D U E E A R D U F MPTOM H N M R AA M AD A V A W R R R W T W L OA OA M OA S O M OO A IIL T HA R A C L O D L E L RR D A D P K D D II E E N O E AM Y D T HAM VA R R R O T T AD CO D N VE OR N O O M Y BBI D ST F COTHAMC R THA I ST A A FORD AA C T R ITIT G D T M O -

Pickwick – Conservation Area Appraisal

Pickwick – Conservation Area Appraisal Produced by Pickwick Association 1 Plans used in this document are based upon Ordnance Survey mapping with the permission of the controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Un- authorised reproduction infringes crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. Corsham Town Council Licence number 100051233 2015 Contains British Geological Survey materials © UKRI [2011] As well as from the authors, images (maps, plans, photos., postcards, aerial views etc.) were sourced from Julian Carosi, Stephen Flavin, Larry St. Croix, Thomas Brakspear and David Rum- ble, to whom we are grateful: if there are any omissions we apologise sincerely. Our thanks also to Cath Maloney (for her editing skills), to Tom Brakspear and Paul Kefford who contributed additional text, and Anne Lock and Melanie Pomeroy-Kellinger who read and helpfully advised. Front Cover picture - The Roundhouse, Pickwick. Back Cover picture - The Hare and Hounds circa 1890 Draft for consultation January 2021 2 Pickwick Conservation Area Appraisal Contents Pickwick – Conservation Area Appraisal : Title Page 1 Copyright acknowledgements 2 Contents 3 Introduction by Thomas Brakspear 4 The Pickwick Association and the Pickwick Conservation Area Appraisal 10 Executive Summary 11 Part 1 – Background to this Review 12 Background 12 The Review 12 Planning Policy Context 14 Purpose and scope of this document 15 Corsham’s Neighbourhood Plan 16 Part 2 – Corsham - its setting and history 17 Geology 17 Location and Setting -

WILTSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position WI_AMAV00 SU 15217 41389 UC road AMESBURY Church Street; opp. No. 41 built into & flush with churchyard wall Stonehenge Road; 15m W offield entrance 70m E jcn WI_AMAV01 SU 13865 41907 UC road AMESBURY A303 by the road WI_AMHE02 SU 12300 42270 A344 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due N of monument on the Verge Winterbourne Stoke Down; 60m W of edge Fargo WI_AMHE03 SU 10749 42754 A344 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Plantation on the Verge WI_AMHE05 SU 07967 43180 A344 SHREWTON Rollestone top of hill on narrow Verge WI_AMHE06 SU 06807 43883 A360 SHREWTON Maddington Street, Shrewton by Blind House against wall on Verge WI_AMHE09 SU 02119 43409 B390 CHITTERNE Chitterne Down opp. tank crossing next to tree on Verge WI_AMHE12 ST 97754 43369 B390 CODFORD Codford Down; 100m W of farm track on the Verge WI_AMHE13 ST 96143 43128 B390 UPTON LOVELL Ansty Hill top of hill,100m E of line of trees on Verge WI_AMHE14 ST 94519 42782 B390 KNOOK Knook Camp; 350m E of entrance W Farm Barns on bend on embankment WI_AMWH02 SU 12272 41969 A303 AMESBURY Stonehenge Down, due S of monument on the Verge WI_AMWH03 SU 10685 41600 A303 WILSFORD CUM LAKE Wilsford Down; 750m E of roundabout 40m W of lay-by on the Verge in front of ditch WI_AMWH05 SU 07482 41028 A303 WINTERBOURNE STOKE Winterbourne Stoke; 70m W jcn B3083 on deep verge WI_AMWH11 ST 990 364 A303 STOCKTON roadside by the road WI_AMWH12 ST 975 356 A303 STOCKTON 400m E of parish boundary with Chilmark by the road WI_AMWH18 ST 8759 3382 A303 EAST KNOYLE 500m E of Willoughby Hedge by the road WI_BADZ08 ST 84885 64890 UC road ATWORTH Cock Road Plantation, Atworth; 225m W farm buildings on the Verge WI_BADZ09 ST 86354 64587 UC road ATWORTH New House Farm; 25m W farmhouse on the Verge Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph WILTSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

Delivering a Wiltshire Regional Network 2020”

Delivering a Regional Rail Service! Connecting Wiltshire’s Communities incorporating TransWilts Community Rail Partnership ROUTE STRATEGY and NEW STATION POLICY “Delivering a Wiltshire Regional Network 2020” [email protected] www.transwilts.org Registered address: 4 Wardour Place, Melksham, Wiltshire, SN12 6AY. Community Interest Company (Company Number 9397959 registered in England and Wales) 2020 Route Strategy Report 24 Feb 2015 v1!Page 1 Delivering a Regional Rail Service! Executive Summary Proposed TransWilts Regional Network builds on the regional service success and provides: • Corsham with an hourly train service 27 minutes to Bristol, 26 minutes to Swindon • Royal Wootton Bassett Parkway (for Lyneham MOD) with two trains per hour service 7 minutes to Swindon • Wilton Parkway (for Stonehenge) with hourly service 6 minutes to Salisbury 56 minutes to Southampton Airport • Swindon to Salisbury hourly train service • Timetable connectivity with national main line services • Adds a direct rail link into Southampton regional airport via Chippenham • Provides all through services without any changes • Rolling stock • 2 electric units (from Reading fleet) post 2017 electrification of line • 1 diesel cascaded from the Stroud line post 2017 electrification, unit which currently waits 70 minutes in every 2 hours at Swindon • 1 diesel from the existing TransWilts service • Existing three diesel units ‘Three Rivers CRP’ used on the airport loop service Salisbury to Romsey. Currently with 40 minute layover at Salisbury, continues on to Swindon. • Infrastructure • A passing loop for IEP trains by reopening the 3rd platform at Chippenham Hub acting as an interchange for regional services • New Stations • Corsham station at Stone Wharf • Royal Wootton Bassett Parkway (for Lyneham) new site east of the old station site serves M4 J16 as a park & ride for Swindon • Wilton Parkway (for Stonehenge) at existing A36 Bus Park and Ride location. -

Introduction

03 Atkins Transport modeling note Technical Note Project: Chippenham Urban Expansion HIF Subject: M4 Junction 17 Author: Reg 13(1) Reviewed by: Reg 13(1) Date: 12/02/2019 Approved by: Reg 13(1) Version: 1.0 Introduction 1.1. Introduction Wiltshire Council are preparing a funding bid to be submitted to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) through the Housing Infrastructure Fund (HIF). The bid seeks to fund a distributor road to the east of Chippenham, from Lackham roundabout of the A350 south west of the town to the A4 London Road, and from the A4 London Road to Parsonage Way in the north. The objective of the distributor road is to aid the delivery of the homes and employment proposals of the Chippenham Urban Expansion. Without the distributor road, the level of development would cause unacceptable levels of delay through Chippenham town centre. However, the proposed growth will also lead to increases in congestion and delay at other points on the highway network, and to resolve these issues Wiltshire Council has proposed a number of mitigation schemes. The mitigation schemes are proposed to be funded by existing CIL and strategic funds where necessary in the short term (by 2024, the opening year of the distributor road) or through expected CIL returns from the proposed development where schemes are required in the longer term. A mitigation scheme was considered necessary at M4 J17, to the north of Chippenham as initial testing of traffic growth suggested that by 2041 the junction would operate significantly over capacity. A meeting between Wiltshire Council’s Chippenham Urban Expansion development team, Homes England and Highways England was held on the 30th January 2019. -

Great Western Signal Box Diagrams 22/06/2020 Page 1 of 40

Great Western Signal Box Diagrams Signal Box Diagrams Signal Box Diagram Numbers Section A: London Division Section B: Bristol Division Section E: Exeter Division Section F: Plymouth Division Section G: Gloucester Division Section H: South Wales Main Line Section J: Newport Area Section K: Taff Vale Railway Section L: Llynvi & Ogmore Section Section M: Swansea District Section N: Vale of Neath Section P: Constituent Companies Section Q: Port Talbot & RSB Railways Section R: Birmingham Division Section S: Worcester Division Section T: North & West Line Section U: Cambrian Railways Section W: Shrewsbury Division Section X: Joint Lines Diagrams should be ordered from the Drawing Sales Officer: Ray Caston 22, Pentrepoeth Road, Bassaleg, NEWPORT, Gwent, NP10 8LL. Latest prices and lists are shown on the SRS web site http://www.s-r-s.org.uk This 'pdf' version of the list may be downloaded from the SRS web site. This list was updated on: 10th April 2017 - shown thus 29th November 2017 - shown thus 23rd October 2018 - shown thus 1st October 2019 - shown thus 20th June 2020 (most recent) - shown thus Drawing numbers shown with an asterisk are not yet available. Note: where the same drawing number appears against more than one signal box, it indcates that the diagrams both appear on the same sheet and it is not necessary to order the same sheet twice. Page 1 of 40 22/06/2020 Great Western Signal Box Diagrams Section A: London Division Section A: London Division A1: Main Line Paddington Arrival to Milton (cont'd) Drawing no. Signal box A1: Main Line Paddington Arrival to Milton Burnham Beeches P177 Drawing no.