126 Chapter 4 the Problem of Zeitoper: the Fate of Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tocc0298notes.Pdf

ERNST KRENEK AT THE PIANO: AN INTRODUCTION by Peter Tregear Ernst Krenek was born on 23 August 1900 in Vienna, the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and grew up in a house that overlooked the original gravesites of Beethoven and Schubert. His parents hailed from Čáslav, in what was then Bohemia, but had moved to the city when his father, an officer in the commissary corps of the Imperial Austro-Hungarian Army, had received a posting there. Vienna, the self-styled ‘City of Music’, considered itself to be the well-spring of a musical tradition synonymous with the core values of western classical music, and so it was no matter that neither of Krenek’s parents was a practising musician of any stature: Ernst was exposed to music – and lots of it – from a very young age. Later in life he recalled with wonder the fact that ‘walking along the paths that Beethoven had walked, or shopping in the house in which Mozart had written “Don Giovanni”, or going to a movie across the street from where Schubert was born, belonged to the routine experiences of my childhood’.1 As befitting an officer’s son, Krenek received formal musical instruction from a young age, in particular piano lessons and instruction in music theory. The existence of a well-stocked music hire library in the city enabled him to become, by his mid-teens, acquainted with the entire standard Classical and Romantic piano literature of the day. His formal schooling coincidentally introduced Krenek to the literature of classical antiquity and helped ensure that his appreciation of this music would be closely associated in his own mind with his appreciation of western history and classical culture more generally. -

Download the Berlin Program

BERLIN The Last NIGHT. THE LAST Cabaret. PRESENTED WITH: VO-Barber COV TLC program half page ad FINAL.indd 1 2019-11-28 8:18 AM The Theatre of Music Alan Corbishley: Artistic Director COMING UP: SEPT/OCT 2020 Music of the Night: The Concert Tour a continued celebration of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s 70th Birthday, touring BC and Alberta. 2021 Canadian Premiere of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize Opera, Angel’s Bone: A contemporary fable that examines the dark motivations and effects of modern day slavery and human trafficking. In partnership with Generously supported by www.soundthealarm.ca CITY OPERA VANCOUVER SOUND THE ALARM: MUSIC/THEATRE THE PUSH INTERNATIONAL PERFORMING ARTS FESTIVAL PRESENT BERLIN THE LAST CABARET A new work devised by Alan Corbishley, Joanna Garfinkel, and Roger Parton Running Time: 90:00. No intermission. Haze and lighting effects. There will be a talk-back immediately following the performances on January 23, 24 and 25, 2020. STARRING Meaghan Chenosky • Daniel Deorksen • Alen Dominguez Brent Hirose • Julia Munčs Alan Corbishley • Stage Director Roger Parton • Music Director, Vocal Coach and Arranger Joanna Garfinkel • Dramaturg John Webber • Set and Lighting Design Christopher David Gauthier • Costume Design Tara Cheyenne Friedenberg • Movement and Choreography Jayson McLean • Production Manager Melanie Thompson • Stage Manager Kattia Woloshyniuk • Ticket Manager Sara Bailey • Graphic and Programme Design Luthor Bonk • Programme Editor Michelle Koebke / Diamond’s Edge • Production Photography Chris Randle • Videographer Murray Paterson Marketing Group • Marketing Trudy Chalmers • General Manager Charles Barber • Artistic Director This production is being given on the traditional territories of the Coast Salish peoples of the Xʷməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By YANG-MING SUN Norman, Oklahoma 2007 UMI Number: 3263429 UMI Microform 3263429 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Edward Gates, chair Dr. Jane Magrath Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Sarah Reichardt Dr. Fred Lee © Copyright by YANG-MING SUN 2007 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is dedicated to my beloved parents and my brother for their endless love and support throughout the years it took me to complete this degree. Without their financial sacrifice and constant encouragement, my desire for further musical education would have been impossible to be fulfilled. I wish also to express gratitude and sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Edward Gates, for his constructive guidance and constant support during the writing of this project. Appreciation is extended to my committee members, Professors Jane Magrath, Eugene Enrico, Sarah Reichardt and Fred Lee, for their time and contributions to this document. Without the participation of the writing consultant, this study would not have been possible. I am grateful to Ms. Anna Holloway for her expertise and gracious assistance. Finally I would like to thank several individuals for their wonderful friendships and hospitalities. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

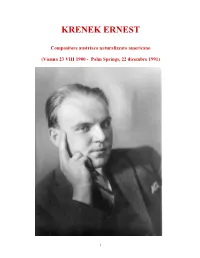

Krenek Ernest

KRENEK ERNEST Compositore austriaco naturalizzato americano (Vienna 23 VIII 1900 - Palm Springs, 22 dicembre 1991) 1 Allievo dal 1916 al 1920 di F. Schreker all'Accademia musicale di Vienna, passò poi alla Hochschule fur Musik di Berlino, dove continuò gli studi con Schreker, ed entrò in proficuo contatto di lavoro con Busoni, A. Schnabel ed altri esponenti del mondo musicale della capitale tedesca. Sposata la figlia di Mahler, Anna (1923) si stabilì in Svizzera ma due anni dopo divorziò e dal 1925 al 1927, su invito di P. Bekker, fu nominato consigliere artistico dell'Opera di Kassel, mettendosi in luce con numerose composizioni teatrali e strumentali ed iniziando un'intensa attività pubblicistica come collaboratore musicale della "Frankfurter Zeitung" e dal 1933 della "Wiener Zeitung”. Ottenuto un successo di portata internazionale con l'opera Jonny spielt auf, dal 1928 si stabilì a Vienna dedicandosi quasi esclusivamente alla composizione, anche qui a contatto con gli ambienti artistici d'avanguardia (Berg, Webern, K. Kraus). Nel 1937 emigrò in America, dove nel 1939 ottenne una cattedra nel Vassar College di Poughkeepsie, presso New York. Dal 1945 ha avuto la cittadinanza americana. Dal 1942 al 1947 ha insegnato nell'Università di Saint Paul, stabilendosi poi a Los Angeles. Dopo la guerra rientrò spesso in Europa, per corsi di composizione, conferenze e concerti. Musicista assai sensibile ai più attuali problemi estetici e di linguaggio, il suo arco creativo rispecchia l'evoluzione spesso contraddittoria delle correnti dell'avanguardia musicale del secolo. L'insegnamento di Schreker lo ha avvicinato nella prima gioventù ad una sorta di espressionismo temperato in senso tardo-romantico, ma ben presto si liberò da quell'influenza per avvicinarsi alle più diverse esperienze musicali. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter Protagonist •T• Zar •T• Santa

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume 11, Number 1 Spring 1993 IN THI S ISSUE I ssues IN THE GERMAN R ECEPTION OF W EILL 7 Stephen Hinton S PECIAL FEATURE: PROTAGON IST AND Z AR AT SANTA F E 10 Director's Notes by Jonathan Eaton Costume Designs by Robert Perdziola "Der Protagonist: To Be or Not to Be with Der Zar" by Gunther Diehl B OOKS 16 The New Grove Dictionary of Opera Andrew Porter Michael Kater's Different Drummers: Jazz in the Culture of Nazi Germany Susan C. Cook Jilrgen Schebera's Gustav Brecher und die Leipziger Oper 1923-1933 Christopher Hailey PERFORMANCES 19 Britten/Weill Festival in Aldeburgh Patrick O'Connor Seven Deadly Sins at the Los Angeles Philharmonic Paul Young Mahagonny in Karlsruhe Andreas Hauff Knickerbocker Holiday in Evanston. IL bntce d. mcclimg "Nanna's Lied" by the San Francisco Ballet Paul Moor Seven Deadly Sins at the Utah Symphony Bryce Rytting R ECORDINGS 24 Symphonies nos. 1 & 2 on Philips James M. Keller Ofrahs Lieder and other songs on Koch David Hamilton Sieben Stucke aus dem Dreigroschenoper, arr. by Stefan Frenkel on Gallo Pascal Huynh C OLUMNS Letters to the Editor 5 Around the World: A New Beginning in Dessau 6 1993 Grant Awards 4 Above: Georg Kaiser looks down at Weill posing for his picture on the 1928 Leipzig New Publications 15 Opera set for Der Zar /iisst sich pltotographieren, surrounded by the two Angeles: Selected Performances 27 Ilse Koegel 0efl) and Maria Janowska (right). Below: The Czar and His Attendants, costume design for t.he Santa Fe Opera by Robert Perdziola. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Ragtime (Well-Tempered), for Large Orchestra Symphony, Mathis der Maler Paul Hindemith aul Hindemith sowed plenty of wild oats his teaching position at the Hochschule für Pduring his apprentice years as a com- Musik in Berlin. poser. In 1921, the year of Ragtime (Well- By 1938 Hindemith’s situation had grown Tempered), he included a fire siren and a so dire that he left for Switzerland, and in canister of sand in the instrumentation for 1940 he proceeded to the United States. That his Kammermusik No. 1, and provoked scan- autumn he joined the faculty of Yale Univer- dal by parodying both the words and music sity, where he remained until 1953 as profes- of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in his lurid sor of music theory and director of the Yale comic opera Das Nusch-Nuschi. By 1929 he Collegium Musicum (the early-music ensem- had managed to spotlight an apparently ble). He became an American citizen in 1946, nude soprano at center-stage in his opera Neues vom Tage. During that decade he was also immersed in many other musical activ- In Short ities: playing viola in the Amar String Quar- Born: November 16, 1895, in Hanau, near tet, which championed new music along Frankfurt, Germany with the classics; serving on the program committee of the Donaueschingen Festival, Died: December 28, 1963, in Frankfurt a hotbed of the latest sounds; embarking on Works composed and premiered: Ragtime a lifelong fascination with early music (mas- (Well-Tempered), composed 1921, incorporating tering the Baroque-era viola d’amore); even a theme from Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue creating some of the first repertoire in the in C minor from the Well-Tempered Clavier, incipient field of electronic music. -

Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School 2012 Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal Laura Neal [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp I am not submitting this version as a PDF. Please let me know if there are any problems in the automatic conversion. Thank you! Recommended Citation Neal, Laura, "Scholarly Program Notes for the Graduate Voice Recital of Laura Neal" (2012). Research Papers. Paper 280. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/280 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES FOR MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL by Laura S. Neal B.S., Murray State University, 2010 B.A., Murray State University, 2010 A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Masters in Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 2012 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL SCHOLARLY PROGRAM NOTES ON MY GRADUATE VOCAL RECITAL By Laura Stone Neal A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters in the field of Music Approved by: Dr. Jeanine Wagner, Chair Dr. Diane Coloton Dr. Paul Transue Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale May 4, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to thank first and foremost my voice teacher and mentor, Dr. Jeanine Wagner for her constant support during my academic studies at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. -

Römische Chorlyrik

RÖMISCHE CHORLYRIK Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) durch die Philosophische Fakultät der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf vorgelegt von Claudia Damm aus Düsseldorf Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Jochem Küppers Prof. Dr. Michael Reichel Mündliche Prüfungen: 26.01.2006, 09.02.2006 1 D 61 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis Danksagung............................................................................................................2 Einleitung................................................................................................................3 1. Chorlyrik in Griechenland.............................................................................9 1.1 Überblick über die Chorlyrik ...................................................................9 1.1.1 Vorbemerkungen zum Begriff ‚Lyrik’ ...........................................9 1.1.2 Die einzelnen Chorliedgattungen..............................................13 1.1.3 Die Hauptvertreter der Chorlieddichtung...................................25 1.2 Die Chöre im Kult und im Drama..........................................................35 1.2.1 Die Chöre im Kult .....................................................................35 1.2.2 Die Chöre im Drama.................................................................40 2. Römische Chorlieder in der Zeit vor Catull ...............................................66 2.1 Die vorliterarische Phase......................................................................66 -

Trude Hesterberg She Opened Her Own Cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921

Hesterberg, Trude Trude Hesterberg she opened her own cabaret, the Wilde Bühne, in 1921. She was also involved in a number of film productions in * 2 May 1892 in Berlin, Deutschland Berlin. She performed in longer guest engagements in Co- † 31 August 1967 in München, Deutschland logne (Metropol-Theater 1913), alongside Massary at the Künstlertheater in Munich and in Switzerland in 1923. Actress, cabaret director, soubrette, diseuse, operetta After the Second World War she worked in Munich as singer, chanson singer theater and film actress, including as Mrs. Peachum in the production of The Threepenny Opera in the Munich „Kleinkunst ist subtile Miniaturarbeit. Da wirkt entwe- chamber plays. der alles oder nichts. Und dennoch ist sie die unberechen- Biography barste und schwerste aller Künste. Die genaue Wirkung eines Chansons ist nicht und unter gar keinen Umstän- Trude Hesterberg was born on 2 May, 1892 in Berlin den vorauszusagen, sie hängt ganz und gar vom Publi- “way out in the sticks” in Oranienburg (Hesterberg. p. 5). kum ab.“ (Hesterberg. Was ich noch sagen wollte…, S. That same year, two events occurred in Berlin that would 113) prove of decisive significance for the life of Getrude Joh- anna Dorothea Helen Hesterberg, as she was christened. „Cabaret is subtle work in miniature. Either everything Firstly, on on 20 August, Max Skladonowsky filmed his works or nothing does. And it is nonetheless the most un- brother Emil doing gymnastics on the roof of Schönhau- predictable and difficult of the arts. The precise effect of ser Allee 148 using a Bioscop camera, his first film record- a chanson is not foreseeable under any circumstances; it ing. -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W.