Moving Forward: 2007 RAP Progress Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Wet Weather Flow Master Plan And

STAFF REPORT ACTION REQUIRED Wet Weather Flow Master Plan and Basement Flooding Protection Program Update Date: August 12, 2011 To: Public Works and Infrastructure Committee From: General Manager, Toronto Water Wards: City-wide Reference P:\2011\Cluster B\TW\pw11012 Number: SUMMARY The purpose of this report is to advise Council of the progress made since the adoption of the Wet Weather Flow Master Plan (WWFMP) in 2003, to set priorities for the next five years and seek approval in principle for the Don River and Central Waterfront Project. Subsequent to the adoption of the WWFMP, the rainstorm of August 2005 and the discovery of significant faults in the Coxwell Sanitary Trunk Sewer have profoundly influenced the implementation of the Plan. As a result, the main funding priorities should be: improving basement flooding protection during extreme storms; twinning of the Coxwell Sanitary Trunk Sewer; elimination of combined sewer overflows; and protection of infrastructure and property from imminent collapse due to stream erosion. All of these priorities are urgent, the solutions very complicated and each will involve several hundreds of millions of dollars to correct. This report recommends that the Basement Flooding Protection Program, the Don River and Central Waterfront Project and the Stream Restoration Program be the main funding priorities for the WWFMP over the next five to ten years. Within those programs, it also recommends a method for prioritizing basement flooding projects and coordinating those projects with the rest of the Capital construction program and recommends a technical amendment to the low income subsidy for the Downspout Disconnection Program. -

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average Price by Percentage Increase: January to June 2016

City of Toronto — Detached Homes Average price by percentage increase: January to June 2016 C06 – $1,282,135 C14 – $2,018,060 1,624,017 C15 698,807 $1,649,510 972,204 869,656 754,043 630,542 672,659 1,968,769 1,821,777 781,811 816,344 3,412,579 763,874 $691,205 668,229 1,758,205 $1,698,897 812,608 *C02 $2,122,558 1,229,047 $890,879 1,149,451 1,408,198 *C01 1,085,243 1,262,133 1,116,339 $1,423,843 E06 788,941 803,251 Less than 10% 10% - 19.9% 20% & Above * 1,716,792 * 2,869,584 * 1,775,091 *W01 13.0% *C01 17.9% E01 12.9% W02 13.1% *C02 15.2% E02 20.0% W03 18.7% C03 13.6% E03 15.2% W04 19.9% C04 13.8% E04 13.5% W05 18.3% C06 26.9% E05 18.7% W06 11.1% C07 29.2% E06 8.9% W07 18.0% *C08 29.2% E07 10.4% W08 10.9% *C09 11.4% E08 7.7% W09 6.1% *C10 25.9% E09 16.2% W10 18.2% *C11 7.9% E10 20.1% C12 18.2% E11 12.4% C13 36.4% C14 26.4% C15 31.8% Compared to January to June 2015 Source: RE/MAX Hallmark, Toronto Real Estate Board Market Watch *Districts that recorded less than 100 sales were discounted to prevent the reporting of statistical anomalies R City of Toronto — Neighbourhoods by TREB District WEST W01 High Park, South Parkdale, Swansea, Roncesvalles Village W02 Bloor West Village, Baby Point, The Junction, High Park North W05 W03 Keelesdale, Eglinton West, Rockcliffe-Smythe, Weston-Pellam Park, Corso Italia W10 W04 York, Glen Park, Amesbury (Brookhaven), Pelmo Park – Humberlea, Weston, Fairbank (Briar Hill-Belgravia), Maple Leaf, Mount Dennis W05 Downsview, Humber Summit, Humbermede (Emery), Jane and Finch W09 W04 (Black Creek/Glenfield-Jane -

Trailside Esterbrooke Kingslake Harringay

MILLIKEN COMMUNITY TRAIL CONTINUES TRAIL CONTINUES CENTRE INTO VAUGHAN INTO MARKHAM Roxanne Enchanted Hills Codlin Anthia Scoville P Codlin Minglehaze THACKERAY PARK Cabana English Song Meadoway Glencoyne Frank Rivers Captains Way Goldhawk Wilderness MILLIKEN PARK - CEDARBRAE Murray Ross Festival Tanjoe Ashcott Cascaden Cathy Jean Flax Gardenway Gossamer Grove Kelvin Covewood Flatwoods Holmbush Redlea Duxbury Nipigon Holmbush Provence Nipigon Forest New GOLF & COUNTRY Anthia Huntsmill New Forest Shockley Carnival Greenwin Village Ivyway Inniscross Raynes Enchanted Hills CONCESSION Goodmark Alabast Beulah Alness Inniscross Hullmar Townsend Goldenwood Saddletree Franca Rockland Janus Hollyberry Manilow Port Royal Green Bush Aspenwood Chapel Park Founders Magnetic Sandyhook Irondale Klondike Roxanne Harrington Edgar Woods Fisherville Abitibi Goldwood Mintwood Hollyberry Canongate CLUB Cabernet Turbine 400 Crispin MILLIKENMILLIKEN Breanna Eagleview Pennmarric BLACK CREEK Carpenter Grove River BLACK CREEK West North Albany Tarbert Select Lillian Signal Hill Hill Signal Highbridge Arran Markbrook Barmac Wheelwright Cherrystone Birchway Yellow Strawberry Hills Strawberry Select Steinway Rossdean Bestview Freshmeadow Belinda Eagledance BordeauxBrunello Primula Garyray G. ROSS Fontainbleau Cherrystone Ockwell Manor Chianti Cabernet Laureleaf Shenstone Torresdale Athabaska Limestone Regis Robinter Lambeth Wintermute WOODLANDS PIONEER Russfax Creekside Michigan . Husband EAST Reesor Plowshare Ian MacDonald Nevada Grenbeck ROWNTREE MILLS PARK Blacksmith -

Hto Park (Central Waterfront)

HtO Park (Central Waterfront) http://urbantoronto.ca/forum/printthread.php?s=bdb9f0791b0c9cf2cb1d... HtO Park (Central Waterfront) Printable View Show 40 post(s) from this thread on one page Page 1 of 9 1 2 3 ... Last AlvinofDiaspar 2006-Nov-16, 14:09 HtO Park (Central Waterfront) From the Star: A vision beyond the urban beach Nov. 16, 2006. 01:00 AM CHRISTOPHER HUME Janet Rosenberg may be in a hurry, but unfortunately Toronto isn't. One of the city's leading landscape architects, Rosenberg desperately wants Toronto to get off its collective butt and get going. She's getting tired of waiting. Take HtO, for example, the "urban beach" at the foot of John St. at Queens Quay W. her firm designed three years ago. The project is underway and slated to open next spring, finally, only two years behind schedule. Much of that time has been spent jumping through bureaucratic hoops. Dealing with the various agencies alone was enough to slow construction to a crawl. Now, however, the results can be seen; the large concrete terraces that reach down to the very waters of Lake Ontario have been poured and the hole that will contain a huge sandpit has been dug and lined. Even a few of the bright yellow umbrellas have been installed. Eventually there will be 39, the bulk still to come. Willow trees have also been planted on mounds and benches installed. Of course, changes were made along the way. After West 8 of Rotterdam won the central waterfront redesign competition last summer, the beach was moved closer to Queens Quay in anticipation of reducing the street from four lanes to two. -

1997Fcprogram.Pdf

THE MIMCO MOUNTAINEERS WOULD LIKE TO THANK THEIR 1997 SPONSORS FOR THEIR SUPPORT Apps ExpressCartage Apps International Logistics Artex Electrical Bestway Cartage 1997 Consolidated Freightways Canadian Junior 'B' Lacrosse Championships Cutler-Hamer Etobicole Professional Fire Fighter's Association HOST COMMITTEE Fonorola Co-Chair jim Surphlis Co-Chair Sean O'Callaghan Gillespie-Munroe Event Coordinators ". Rob Michalsky · Brian Shanahan G "N" R Pro Shop · Mark Grimes Homelife Realty - Betty Bailey ................................ john Robinson Hub Group Canada · Bernie Sauve · jack Foote Kingsway Landscaping · Christine Neary Laser 1000 - Margaret McGonigle Volunter Coordinator Lynda O'Callaghan Lazer-Tech Limited VOLUNTEERS Lex Metal Ltd. Kelly O'Cailaghan joe O'Callaghan Brenda Borrow Liberty Health Howie Borrow Sheila Petrovic Darlene Priestman Michelle Robinson Ginette Surphlis Bob McCabe McDonald's Restaurants of Canada Scottie Gillingham Rick Ellul Roger McKeen Midland Walwyn Bill McAlpine Sarah Calvert Nicole Sauve Mimico-Lakeshore Lacrosse Alumni Gord Mackenzie Mick jenkins Mimico Pharmacy Mimico Minor Lacrosse Club CANADIAN LACROSSEASSOCIATION Chairman of the Board Bill Hutton Technical Director Mike Lachapelle Motorola Vice-President, Technical jim Price Neulaps Automotive PennLife Corp Insurance ONTARIO JUNIOR 'B' COUNCIL Commissioner Dave Vernon Pristine Printi ng Secretary-Treasurer Vince Ladouceur Queensway Minor Hockey Association CITY OF ETOBICOKE Rick's Tree Maintenance Director of Facilities Bill Channing R.B. Bannon Canada Royal LePage- Angela and Paul Giruady MIMICO ARE A STAFF Manager Don Thompason Sky Tracker of Canada Assistant Manager Ivan Krympotich Systemsearch Maintenance Clay Stewart The Blue Goose Tavern .......................... Peter King Total Auto Glass WhiteOak Lincoln Mercury Mimico's own Brendan Shanahan of the Stanley Cup winning Detroit Red Wings and Brian Shanahan, of the Mann Cup Champion Six Nations Chiefs pose with their respective trophies, the Stanley and Mann Cups. -

Attachment 1: Table of Projects Being Planned Under the ERMP in 2021

Attachment 1: Table of projects being planned under the ERMP in 2021 Municipality Ward Project Name Portfolio 2021 Project Status City of Brampton 2 Wegneast Valley Erosion Control Project Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Construction City of Brampton 7 I-360/I-361 Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Study, Planning or Design York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Markham 1 German Mills Settlers Park Sites 2-3 Sanitary Infrastructure Protection Management Program Study, Planning or Design City of Markham 4 70 Main Street South Erosion Control Project TRCA Maintenance & Other Hazards (York Region) Construction City of Mississauga 5 Brandon Gate Park - Bank Stabilization Project Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Construction City of Mississauga 5 I-700 Region of Peel Erosion Control & Infrastructure Protection Study, Planning or Design York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Creek I-066, I-067, I-065, I-064, P-102 Management Program Post-Construction York Region Streambank Infrastructure Erosion Control City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Creek near North Richvale Sanitary Infrastructure Protection Management Program Construction City of Richmond Hill 5 Patterson Valley South Richvale Erosion Hazards Fee For Service Post-Construction City of Toronto 1 22-24 Bucksburn Road Erosion Control and Slope Stabilization Project Valley Erosion Hazards Study, Planning or Design City of Toronto 1 Hadrian Drive -

Festival Guide

FESTIVAL GUIDE DU GUÍA DEL GUIDE FESTIVAL FESTIVAL July 10–August 15, 2015 10 juillet au 15 août 2015 10 julio – 15 agosto 2015 LEAD PARTNER PARTENAIRE PRINCIPAL SOCIO PRINCIPAL PREMIER PARTNERS GRANDS PARTENAIRES SOCIOS PREMIERES OPENING CEREMONY CREATIVE PARTNER OFFICIAL BROADCASTER PARTENAIRE CRÉATIF POUR LA CÉRÉMONIE D’OUVERTURE DIFFUSEUR OFFICIEL SOCIO CREATIVO PARA LA CEREMONIA DE INAUGURACIÓN EMISORA OFICIAL OFFICIAL SUPPLIERS FOURNISSEURS OFFICIELS PROVEEDORES OFICIALES PROUD SUPPORTERS FIERS PARRAINEURS COLABORADORES PRINCIPALES Acklands-Grainger ATCO Structures & Logistics Ltd. Bochner Eye Institute BT/A Advertising Burnbrae Farms The Canadian Press Carbon60 Networks The Carpenters’ Union CGC Inc. Division Sports-Rep Inc. ELEIKO EllisDon-Ledcor Esri Canada eSSENTIAL Accessibility Freeman Audio Visual Canada Gateman-Milloy Inc. George Brown College Gerflor Gold Medal Systems La Presse LifeLabs Medical Laboratory Services MAC Cosmetics Minavox Modu-loc Fence Rentals Morningstar Hospitality Services Inc. Nautique Boats ONRoute Highway Service Centres Ontario Power Generation PortsToronto Riedel Communications Roots Rosetta Stone SpiderTech Sportsnet 590 The Fan S4OPTIK Starwood Hotels and Resorts TBM Service Group TLN Telelatino Toronto Port Lands Company UP Express VIA Rail Canada VOIT Vision Critical Waste Management Yonex YouAchieve ZOLL 407 ETR FUNDING PARTIES HOST CITY HOST FIRST NATION BAILLEURS DE FONDS VILLE HÔTE PREMIÈRE NATION HÔTE PROVEEDORES DE FINANCIAMIENTO CIUDAD ANFITRIONA PRIMERA NACIÓN ANFITRIONA Live Sites/Sites -

MATT ,ESS [Et: 1 12 E -R 2 Lynden Rd -Ter Ieret -184 Lynden Road, I( DELIVERY Lyndon MATTRESS BRANDS Park Mall Mattress Ilk BRANTFORD Brands Int

.r, . Y t-ter T LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA 1 t Bibliot leque et Archives Canada tJSvR,NA s1oS 11 II II I! II I I II 111 3 32 6 53873950 5 T-j y I 19 Library & Archives ana. a Newspaper Collection l r 74 i 395 Wellington St. North America's #1 Native W Ottawa. ON K1A ON4 Pub. No. 40016309 Kids have fun while learning at Bite of Brant I Reg. No. 10963 ...See page 7 Okarahshona kenh Onkwehonwene, Six Nations of the Grand Wednesday April 16, 2008 Confederacy mulls over 4 Ontario's `no go zone' i offer I .4 M By Mark Ladan Sd.a - Z «evgr,!'.:; Writer The Six Nations Confederacy council wants more informa- tion before making a decision on an Ontario offer of a two - year development moratorium within the Haldimand Tract. Lead provincial negotiator Murray banned for two years. Coolican made the offer when he The Confederacy Chiefs further 1 spoke at the council's Apr. 5 meet- discussed the matter at a special 11 ing. meeting of the council on Apr. 11. 'il Coolican suggested that any devel- Cayuga sub -Chief Leroy Hill said opment currently underway within it has been deferred to the six - 't the Tract should be allowed to pro- member Chiefs committee that has t ceed, but the Confederacy council been appointed to oversee the land would be allowed to draw up a list rights negotiating process. of so- called "no go zones," in which development would be (Continued on page 3) Ve "Sick" school shut down, ti students moved . -

Toronto Central Waterfront Public Forum #2

TORONTO CENTRAL WATERFRONT PUBLIC FORUM #2 Queens Quay Revitalization EA Bathurst Street to Lower Jarvis Street Municipal Class Environmental Assessment (Schedule C) December 08, 2008 1 WATERFRONT TORONTO UPDATE 2 Central Waterfront International Design Competition 3 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 4 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 5 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 6 Waterfront Toronto Long Term Plan – Central Waterfront 7 East Bayfront Waters Edge Promenade: Design Underway 8 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 9 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 10 Spadina Wavedeck: Opened September 2008 Metropolis Article 11 Rees Wavedeck: Construction Underway 12 Simcoe Wavedeck: Construction Underway 13 Spadina Bridge: Construction Early-2009 14 What Have We Been Doing for the Past 11 Months? • Consider and follow up on comments from Public Forum 1 • Assess baseline technical feasibility of design alternatives – Over 90 meetings in total: • City and TTC technical staff • Partner agencies •Stakeholders • Landowners/Property Managers • Adjacent project efforts • Advanced transit and traffic modelling • Develop Alternative Design Concepts and Evaluation (Phase 3) • Coordination with East Bayfront Transit EA 15 Study Area: Revised 16 Overview • Review of EA Phases 1 & 2 from Public Forum #1: January 2008 • EA Phase 3: Alternative Design Alternatives – Long list of Design Alternatives – Evaluation of Design Alternatives • Next Steps – Evaluation Criteria for Shortlisted Design -

Round 1 - Pick 1

Round 1 - Pick 1 OJALL ontario junior ‘a’ lacrosse league Jeff teat Brampton Excelsiors Round 1 - Pick 3 Round 1 - Pick 5 Round 1 - Pick 6 Round 1 - Pick 7 Round 1 - Pick 8 Round 1 - Pick 10 Round 1 - Pick 11 RYAN SMITH TANNER COOK ROBERT HUDSON MARSHALL POWELESS JEFF HENRICK ETHAN WALKER ETHAN RIGGS OAKVILLE ROCK WHITBY WARRIORS BRAMPTON EXCELSIORS SIX NATIONS ARROWS ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN PETERBOROUGH LAKERS BURLINGTON CHIEFS Round 1 - Pick 12 Round 1 - Pick 15 Round 1 - Pick 16 Round 2 - Pick 17 Round 2 - Pick 18 Round 2 - Pick 23 Round 2 - Pick 24 CONNOR MCLELLAND MAC O’KEEFE JACKSON SUBOCH MATHIEU BOISSONNEAULT RON JOHN JORDAN STOUROS CHARLIE KITCHEN Brampton Excelsiors ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN BROOKLIN LC WHITBY WARRIORS SIX NATIONS ARROWS PETERBOROUGH LAKERS TORONTO BEACHES Round 2 - Pick 25 Round 2 - Pick 29 Round 3 - Pick 38 Round 3 - Pick 39 Round 3 - Pick 40 Round 3 - Pick 44 Round 3 - Pick 46 TY THOMPSON ANDREW BORGATTI KEVIN OWEN HILL SAM FIRTH CURTIS CONLEY ADAM KROMER PHIL MAZZUCA NEPEAN KNIGHTS KITCHENER BRAVES SIX NATIONS ARROWS ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN TORONTO BEACHES WHITBY WARRIORS OAKVILLE BUZZ Round 3 - Pick 47 Round 3 - Pick 48 Round 3 - Pick 51 Round 4 - Pick 53 Round 4 - Pick 54 Round 4 - Pick 56 Round 4 - Pick 57 LACROSSE MATT GAUDET OWEN FRIESEN BEN FRENCH KRIS VELTMAN MITCH OGILVIE ROBBIE STOVEL JONAH BOEHM MIMICO MOUNTAINEERS ST. CATHARINES ATHLETICS COBOURG KODIAKS WEST DURHAM IRONHEADS PETERBOROUGH LAKERS Brampton Excelsiors KITCHENER BRAVES Round 4 - Pick 60 Round 4 - Pick 62 Round 4 - Pick 63 Round 4 - Pick 67 Round 5 - Pick 70 Round 5 - Pick 73 Round 5 - Pick 74 TANNER BUCK CHRIS WEIER brody mclean curtis romanchych john vezina tye argent john kit ORANGEVILLE NORTHMEN Niagara thunderhawks kitchener braves orangeville northmen Brampton Excelsiors hamilton bengals st. -

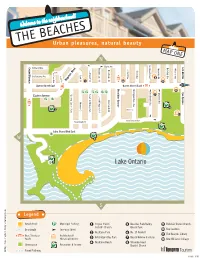

90Ab-The-Beaches-Route-Map.Pdf

THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP ONE N Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Coxw Dixon Ave Bell Brookmount Rd Wheeler Ave Wheeler Waverley Rd Waverley Ashland Ave Herbert Ave Boardwalk Dr Lockwood Rd Elmer Ave efair Ave efair O r c h ell A ell a r d Lark St Park Blvd Penny Ln venu Battenberg Ave 8 ingston Road K e 1 6 9 Queen Street East Queen Street East Woodbine Avenue 11 Kenilworth Ave Lee Avenue Kippendavie Ave Kippendavie Ave Waverley Rd Waverley Sarah Ashbridge Ave Northen Dancer Blvd Eastern Avenue Joseph Duggan Rd 7 Boardwalk Dr Winners Cir 10 2 Buller Ave V 12 Boardwalk Dr Kew Beach Ave Al 5 Lake Shore Blvd East W 4 3 Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking Corpus Christi Beaches Park/Balmy Bellefair United Church g 1 5 9 Catholic Church Beach Park 10 Kew Gardens . Desi Boardwalk One-way Street d 2 Woodbine Park 6 No. 17 Firehall her 11 The Beaches Library p Bus, Streetcar Architectural/ he Ashbridge’s Bay Park Beach Hebrew Institute S 3 7 Route Historical Interest 12 Kew Williams Cottage 4 Woodbine Beach 8 Waverley Road : Diana Greenspace Recreation & Leisure g Baptist Church Writin Paved Pathway BEACH_0106 THE BEACHESUrban pleasures, natural beauty MAP TWO N H W Victoria Park Avenue Nevi a S ineva m Spruc ca Lee Avenue Kin b Wheeler Ave Wheeler Balsam Ave ly ll rbo Beech Ave Willow Ave Av Ave e P e Crown Park Rd gs Gle e Hill e r Isleworth Ave w o ark ark ug n Manor Dr o o d R d h R h Rd Apricot Ln Ed Evans Ln Blvd Duart Park Rd d d d 15 16 18 Queen Street East 11 19 Balsam Ave Beech Ave Willow Ave Leuty Ave Nevi Hammersmith Ave Hammersmith Ave Scarboro Beach Blvd Maclean Ave N Lee Avenue Wineva Ave Glen Manor Dr Silver Birch Ave Munro Park Ave u Avion Ave Hazel Ave r sew ll Fernwood Park Ave Balmy Ave e P 20 ood R ark ark Bonfield Ave Blvd d 0 Park Ave Glenfern Ave Violet Ave Selwood Ave Fir Ave 17 12 Hubbard Blvd Silver Birch Ave Alfresco Lawn 14 13 E Lake Ontario S .com _ gd Legend n: www.ns Beach Front Municipal Parking g 13 Leuty Lifesaving Station 17 Balmy Beach Club . -

The Fish Communities of the Toronto Waterfront: Summary and Assessment 1989 - 2005

THE FISH COMMUNITIES OF THE TORONTO WATERFRONT: SUMMARY AND ASSESSMENT 1989 - 2005 SEPTEMBER 2008 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank the many technical staff, past and present, of the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority and Ministry of Natural Resources who diligently collected electrofishing data for the past 16 years. The completion of this report was aided by the Canada Ontario Agreement (COA). 1 Jason P. Dietrich, 1 Allison M. Hennyey, 1 Rick Portiss, 1 Gord MacPherson, 1 Kelly Montgomery and 2 Bruce J. Morrison 1 Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, 5 Shoreham Drive, Downsview, ON, M3N 1S4, Canada 2 Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Lake Ontario Fisheries Management Unit, Glenora Fisheries Station, Picton, ON, K0K 2T0, Canada © Toronto and Region Conservation 2008 ABSTRACT Fish community metrics collected for 16 years (1989 — 2005), using standardized electrofishing methods, throughout the greater Toronto region waterfront, were analyzed to ascertain the current state of the fish community with respect to past conditions. Results that continue to indicate a degraded or further degrading environment include an overall reduction in fish abundance, a high composition of benthivores, an increase in invasive species, an increase in generalist species biomass, yet a decrease in specialist species biomass, and a decrease in cool water Electrofishing in the Toronto Harbour thermal guild species biomass in embayments. Results that may indicate a change in a positive community health direction include no significant changes to species richness, a marked increase in diversity in embayments, a decline in non-native species in embayments and open coasts (despite the invasion of round goby), a recent increase in native species biomass, fluctuating native piscivore dynamics, increased walleye abundance, and a reduction in the proportion of degradation tolerant species.