Contextualising Wasaṭiyyah from the Perspective of the Leaders of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Malaysian Intellectual:A Briefsari Historical 27 (2009) Overview 13 - 26 of the Discourse 13

The Malaysian Intellectual:A BriefSari Historical 27 (2009) Overview 13 - 26 of the Discourse 13 The Malaysian Intellectual: A Brief Historical Overview of the Discourse DEBORAH JOHNSON ABSTRAK Kertas ini memperkatakan wacana yang melibatkan intelektual di Malaysia. Ia menegaskan bahawa sesuai dengan perubahan sosio-politik, ‘bidang makna’ yang berkaitan konsep ‘intelektual’ dan lokasi sosial sebenar para intelektual itu sudah mengalami perubahan besar sepanjang abad dua puluh. Ini menimbulkan cabaran kepada sejarahwan yang ingin melihat masa lampau dengan kaca mata masa kini tetapi yang sepatutnya perlu difahami dengan tanggapan yang ikhlas sesuai dengan masanya. Selain itu, ia juga menimbulkan cabaran kepada penyelidik sains sosial untuk mengelak dari mengaitkan konsep masa lampau kepada konsep masa terkini supaya dapat memahami sumbangan ide dan kaitannya kepada masa lampau. Sehubungan itu, makalah ini memberi bayangan sekilas tentang persekitaran, motivasi dan sumbangan beberapa tokoh intelektual yang terkenal di Malaysia. Kata kunci: A Samad Ismail, intelektual, wacana, Alam Melayu ABSTRACT This paper focuses on the discourse in Malaysia concerning intellectuals. It asserts that in concert with political and sociological changes, the ‘field of meanings’ associated with the concept of ‘the intellectual’ and the actual social location of intellectual actors have undergone considerable change during the twentieth century. This flags the challenge for historians who are telling today’s stories about the past in today’s terms, but who have to try to understand that past on its own terms. Further, it flags the challenge for social scientists to not merely appropriate the concepts of past scholars in tying to understand the present, but rather to also understand the context in which those ideas had relevance. -

And Bugis) in the Riau Islands

ISSN 0219-3213 2018 no. 12 Trends in Southeast Asia LIVING ON THE EDGE: BEING MALAY (AND BUGIS) IN THE RIAU ISLANDS ANDREW M. CARRUTHERS TRS12/18s ISBN 978-981-4818-61-2 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg 9 789814 818612 Trends in Southeast Asia 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 1 19/6/18 8:05 AM The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute (formerly Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) is an autonomous organization established in 1968. It is a regional centre dedicated to the study of socio-political, security, and economic trends and developments in Southeast Asia and its wider geostrategic and economic environment. The Institute’s research programmes are grouped under Regional Economic Studies (RES), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). The Institute is also home to the ASEAN Studies Centre (ASC), the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre (NSC) and the Singapore APEC Study Centre. ISEAS Publishing, an established academic press, has issued more than 2,000 books and journals. It is the largest scholarly publisher of research about Southeast Asia from within the region. ISEAS Publishing works with many other academic and trade publishers and distributors to disseminate important research and analyses from and about Southeast Asia to the rest of the world. 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 2 19/6/18 8:05 AM 2018 no. 12 Trends in Southeast Asia LIVING ON THE EDGE: BEING MALAY (AND BUGIS) IN THE RIAU ISLANDS ANDREW M. CARRUTHERS 18-J04027 01 Trends_2018-12.indd 3 19/6/18 8:05 AM Published by: ISEAS Publishing 30 Heng Mui Keng Terrace Singapore 119614 [email protected] http://bookshop.iseas.edu.sg © 2018 ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore All rights reserved. -

An Islamic Perspective

Islam and Civilisational Renewal A journal devoted to contemporary issues and policy research Special Issue: Religion, Law, and Governance in Southeast Asia Volume 2 • Number 1 • October 2010 Produced and distributed by ISSN 2041–871X (Print) ISSN 2041–8728 (Online) © INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED ISLAMIC STUDIES 2010 ICR 2-1 00 prelims 1 28/09/2010 11:06 ISLAM AND CIVILISATIONAL RENEWAL EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Professor Mohammad Hashim Kamali EDITOR Professor Emeritus Datuk Osman Bakar ASSOCIATE EDITOR Christoph Marcinkowski ADVISORY BOARD Mahmood Zuhdi Hj Abdul Mostafa Mohaghegh Damad, Sachiko Murata, United States Majid, Malaysia Islamic Republic of Iran Chandra Muzaffar, Malaysia Ibrahim Abu Rabi‘, Canada Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkey Seyyed Hossein Nasr, United Syed Farid Alatas, Singapore W. Cole Durham Jr, United States Syed Othman Al-Habshi, States Mohamed Fathi Osman, Canada Malaysia John Esposito, United States Tariq Ramadan, United Amin Abdullah, Indonesia Marcia Hermansen, United Kingdom Zafar Ishaq Ansari, Pakistan States Miroslav Volf, United States Azyumardi Azra, Indonesia Ekmeleddin Ihsanoğlu, Turkey John O. Voll, United States Azizan Baharuddin, Malaysia Anthony H. Johns, Australia Abdul Hadi Widji Muthari, Shamsul Amri Baharuddin, Yasushi Kosugi, Japan Indonesia Malaysia Khalid Masud, Pakistan Timothy Winter (alias Abdal Mustafa Cerić, Bosnia Ingrid Mattson, United States Hakim Murad), United Herzegovina Ali A. Mazrui, United States Kingdom Murat Çizakça, Turkey Khalijah Mohd Salleh, Malaysia OBJECTIVES AND SCOPE • Islam and Civilisational Renewal (ICR) is an international peer-reviewed journal published by Pluto Journals on behalf of the International Institute of Advanced Islamic Studies (IAIS). It carries articles, book reviews and viewpoints on civilisational renewal. • ICR seeks to advance critical research and original scholarship on theoretical, empirical, historical, inter-disciplinary and comparative studies, with a focus on policy research. -

Sup. No. 4 32 Head I

Sup. No. 4 32 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Head I - Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports That the total sum to be allocated for Head I of the Estimates be reduced by $100. (a) Plans in Event of Economic Slowdown Mr Seah Kian Peng (b) Improve Access and Review Eligibility Mr Seah Kian Peng (c) Malay/Muslim Community of the Future Assoc. Prof. Fatimah Lateef (d) Empowering the Poor, Needy and Low-skilled Assoc. Prof. Dr Muhammad Faishal Ibrahim (e) Empowering the Poor, Needy and Low-skilled Assoc. Prof. Fatimah Lateef (f) Madrasah Education and Training Teachers Assoc. Prof. Fatimah Lateef (g) Performance of Madrasahs under Joint Madrasah System Mr Zaqy Mohamad (h) Tertiary Tuition Subsidy Scheme Mr Zainudin Nordin (i) Yayasan Mendaki Tuition Scheme Mr Zainudin Nordin (j) Self-help Groups and Minor Marriages Dr Intan Azura Mokhtar (k) Strengthening Muslim Institutions Mr Hawazi Daipi (l) Mosque Management Mr Muhamad Faisal Abdul Manap (m) Upgrading of Mosques Assoc. Prof. Dr Muhammad Faishal Ibrahim (n) Mosque Upgrading Programme Mr Hawazi Daipi (o) Sustainability of Mosque Building and Mendaki Fund Mr Zaqy Mohamad Sup. No. 4 33 ______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Head I - Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports - continued (p) Mosque Building Mr Zainal Sapari (q) A Progressive -

Votes and Proceedings of the Twelfth Parliament of Singapore

VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE TWELFTH PARLIAMENT OF SINGAPORE First Session MONDAY, 13 MAY 2013 No. 54 1.30 pm 386 PRESENT: Mdm SPEAKER (Mdm HALIMAH YACOB (Jurong)). Mr ANG WEI NENG (Jurong). Mr BAEY YAM KENG (Tampines). Mr CHAN CHUN SING (Tanjong Pagar), Acting Minister for Social and Family Development and Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Defence. Mr CHEN SHOW MAO (Aljunied). Dr CHIA SHI-LU (Tanjong Pagar). Mrs LINA CHIAM (Non-Constituency Member). Mr CHARLES CHONG (Joo Chiat), Deputy Speaker. Mr CHRISTOPHER DE SOUZA (Holland-Bukit Timah). Ms FAIZAH JAMAL (Nominated Member). Mr NICHOLAS FANG (Nominated Member). Mr ARTHUR FONG (West Coast). Mr CEDRIC FOO CHEE KENG (Pioneer). Ms FOO MEE HAR (West Coast). Ms GRACE FU HAI YIEN (Yuhua), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for the Environment and Water Resources and Second Minister for Foreign Affairs. Mr GAN KIM YONG (Chua Chu Kang), Minister for Health and Government Whip. Mr GAN THIAM POH (Pasir Ris-Punggol). Mr GERALD GIAM YEAN SONG (Non-Constituency Member). Mr GOH CHOK TONG (Marine Parade). No. 54 13 MAY 2013 387 Mr HAWAZI DAIPI (Sembawang), Senior Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Education and Acting Minister for Manpower. Mr HENG CHEE HOW (Whampoa), Senior Minister of State, Prime Minister's Office and Deputy Leader of the House. Mr HRI KUMAR NAIR (Bishan-Toa Payoh). Ms INDRANEE RAJAH (Tanjong Pagar), Senior Minister of State, Ministry of Law and Ministry of Education. Dr INTAN AZURA MOKHTAR (Ang Mo Kio). Mr S ISWARAN (West Coast), Minister, Prime Minister's Office, Second Minister for Home Affairs and Second Minister for Trade and Industry. -

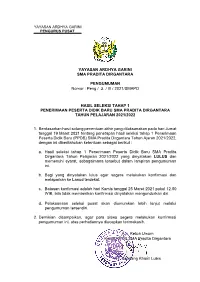

Pengumuman-Tahap-1-Ppdb

YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI PENGURUS PUSAT YAYASAN ARDHYA GARINI SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA PENGUMUMAN Nomor : Peng / 2 / III / 2021/SMAPD HASIL SELEKSI TAHAP 1 PENERIMAAN PESERTA DIDIK BARU SMA PRADITA DIRGANTARA TAHUN PELAJARAN 2021/2022 1. Berdasarkan hasil sidang penentuan akhir yang dilaksanakan pada hari Jumat tanggal 19 Maret 2021 tentang penetapan hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru (PPDB) SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Ajaran 2021/2022, dengan ini diberitahukan ketentuan sebagai berikut : a. Hasil seleksi tahap 1 Penerimaan Peserta Didik Baru SMA Pradita Dirgantara Tahun Pelajaran 2021/2022 yang dinyatakan LULUS dan memenuhi syarat, sebagaimana tersebut dalam lampiran pengumuman ini. b. Bagi yang dinyatakan lulus agar segera melakukan konfirmasi dan melaporkan ke Lanud terdekat. c. Batasan konfirmasi adalah hari Kamis tanggal 25 Maret 2021 pukul 12.00 WIB, bila tidak memberikan konfirmasi dinyatakan mengundurkan diri. d. Pelaksanaan seleksi pusat akan diumumkan lebih lanjut melalui pengumuman tersendiri. 2. Demikian disampaikan, agar para siswa segera melakukan konfirmasi pengumuman ini, atas perhatiannya diucapkan terimakasih. A.n. Ketua Umum Ketua PPDB SMA Pradita Dirgantara Ny. Sondang Khairil Lubis Lampiran Pengumuman Daftar Nama Peserta Lolos Seleksi Tahap 1 NO KODE DAFTAR NAMA JK ASAL PANDA 1 2 3 4 5 1 PRAK-83JQEKIC Az Zahra Leilany Widjanarka P Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 2 PRAK-8TM1YQGC Glenn Emmanuel Abraham L Lanud Abdul Rachman Saleh (ABD), Malang 3 PRAK-202101-0879 Kayana Nur Ramadhania P Lanud Abdul -

Peraturan Badan Informasi Geospasial

PERATURAN BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA NOMOR 16 TAHUN 2019 TENTANG SATUAN HARGA PENYELENGGARAAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL TAHUN ANGGARAN 2020 PADA BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL KEPALA BADAN INFORMASI GEOSPASIAL REPUBLIK INDONESIA, Menimbang : a. bahwa untuk mendukung penyelenggaraan informasi geospasial melalui mekanisme pengadaan barang/jasa pemerintah, diperlukan satuan harga lain selain standar biaya masukan sebagaimana telah ditetapkan dengan Peraturan Menteri Keuangan; b. bahwa berdasarkan ketentuan Pasal 8 ayat (2) huruf b Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 71/PMK.02/2013 tentang Pedoman Standar Biaya, Standar Struktur Biaya, dan Indeksasi Dalam Penyusunan Rencana Kerja dan Anggaran Kementerian Negara/Lembaga sebagaimana telah diubah dengan Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 51/PMK.02/2014 tentang Perubahan Atas Peraturan Menteri Keuangan Nomor 71/PMK.02/2013 tentang Pedoman Standar Biaya, Standar Struktur Biaya, dan Indeksasi Dalam Penyusunan Rencana Kerja dan Anggaran Kementerian Negara/Lembaga, Kepala Badan Informasi Geospasial diberikan kewenangan untuk menetapkan satuan harga; - 2 - c. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud dalam huruf a, dan huruf b, perlu menetapkan Peraturan Badan Informasi Geospasial tentang Satuan Harga Penyelenggaraan Informasi Geospasial Tahun Anggaran 2020 pada Badan Informasi Geospasial; Mengingat : 1. Peraturan Presiden Nomor 16 Tahun 2018 tentang Pengadaan Barang/Jasa Pemerintah (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 2018 Nomor 33); 2. Peraturan Presiden Nomor 94 Tahun 2011 tentang -

Major Vote Swing

BT INFOGRAPHICS GE2015 Major vote swing Bukit Batok Sengkang West SMC SMC Sembawang Punggol East GRC SMC Hougang SMC Marsiling- Nee Soon Yew Tee GRC GRC Chua Chu Kang Ang Mo Kio Holland- GRC GRC Pasir Ris- Bukit Punggol GRC Hong Kah Timah North SMC GRC Aljunied Tampines Bishan- GRC GRC Toa Payoh East Coast GRC GRC West Coast Marine GRC Parade Tanjong Pagar GRC GRC Fengshan SMC MacPherson SMC Mountbatten SMC FOUR-MEMBER GRC Jurong GRC Potong Pasir SMC Chua Chu Kang Registered voters: 119,931; Pioneer Yuhua Bukit Panjang Radin Mas Jalan Besar total votes cast: 110,191; rejected votes: 2,949 SMC SMC SMC SMC SMC 76.89% 23.11% (84,731 votes) (25,460 votes) PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY (83 SEATS) WORKERS’ PARTY (6 SEATS) PEOPLE’S PEOPLE’S ACTION PARTY POWER PARTY Gan Kim Yong Goh Meng Seng Low Yen Ling Lee Tze Shih SIX-MEMBER GRC Yee Chia Hsing Low Wai Choo Zaqy Mohamad Syafarin Sarif Ang Mo Kio Pasir Ris-Punggol 2011 winner: People’s Action Party (61.20%) Registered voters: 187,771; Registered voters: 187,396; total votes cast: 171,826; rejected votes: 4,887 total votes cast: 171,529; rejected votes: 5,310 East Coast Registered voters: 99,118; 78.63% 21.37% 72.89% 27.11% total votes cast: 90,528; rejected votes: 1,008 (135,115 votes) (36,711 votes) (125,021 votes) (46,508 votes) 60.73% 39.27% (54,981 votes) (35,547 votes) PEOPLE’S THE REFORM PEOPLE’S SINGAPORE ACTION PARTY PARTY ACTION PARTY DEMOCRATIC ALLIANCE Ang Hin Kee Gilbert Goh J Puthucheary Abu Mohamed PEOPLE’S WORKERS’ Darryl David Jesse Loo Ng Chee Meng Arthero Lim ACTION PARTY PARTY Gan -

Al Azhar - Study Exchange Programme

Al Azhar - Study Exchange Programme Egypt and England – a significant study exchange: Christians and Muslims learning about each other’s faith A significant development and strengthening of the relationship between the Anglican Communion and Al Azhar Al Sharif, the centre of Islamic learning in Cairo, Egypt, has taken place during November through two significant study visits. The first is that of the Grand Mufti of Egypt, His Eminence Dr Ali Gomaa, who delivered a talk at the University of Cambridge during the first week of November. A longer stay for study, of a month’s duration, was made by three younger Muslim scholars (El Sayed Mohamed Abdalla Amin, Farouk Rezq Bekhit Sayyid, Sameh Mustafa Muhammad Asal, graduate teaching assistants at the Faculty of Languages and Translation, Department of Islamic Studies in English, Al Azhar University) to Ridley Hall Theological College, Cambridge, England, November 1-29. Ridley Hall is well-known as a training centre for future Anglican clergy. Study exchange linked to Anglican Communion Al Azhar dialogue This double visit, of both Dr Gomaa, an eminent international Muslim scholar, and of three future Muslim religious leaders, is linked to the study exchange agreement signed by the Anglican Communion and Al Azhar Al Sharif in September 2005 at Lambeth Palace and ratified in the presence of Sheikh Al Azhar, Dr Mohamed Tantawy, at a meeting held at Al Azhar in September 2006. This process of study exchange has been developed to further the aims of the initial agreement between the Anglican Communion -

Sexuality, Islam and Politics in Malaysia: a Study of the Shifting Strategies of Regulation

SEXUALITY, ISLAM AND POLITICS IN MALAYSIA: A STUDY OF THE SHIFTING STRATEGIES OF REGULATION TAN BENG HUI B. Ec. (Soc. Sciences) (Hons.), University of Sydney, Australia M.A. in Women and Development, Institute of Social Studies, The Netherlands A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2012 ii Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation was made possible with the guidance, encouragement and assistance of many people. I would first like to thank all those whom I am unable to name here, most especially those who consented to being interviewed for this research, and those who helped point me to relevant resources and information. I have also benefited from being part of a network of civil society groups that have enriched my understanding of the issues dealt with in this study. Three in particular need mentioning: Sisters in Islam, the Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies (CSBR), and the Kartini Network for Women’s and Gender Studies in Asia (Kartini Asia Network). I am grateful as well to my colleagues and teachers at the Department of Southeast Asian Studies – most of all my committee comprising Goh Beng Lan, Maznah Mohamad and Irving Chan Johnson – for generously sharing their intellectual insights and helping me sharpen mine. As well, I benefited tremendously from a pool of friends and family who entertained my many questions as I tried to make sense of my research findings. My deepest appreciation goes to Cecilia Ng, Chee Heng Leng, Chin Oy Sim, Diana Wong, Jason Tan, Jeff Tan, Julian C.H. -

RELIGIOUS PEACE a Precious Treasure RELIGIOUS PEACE a Precious Treasure

RELIGIOUS PEACE A Precious Treasure RELIGIOUS PEACE A Precious Treasure Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies (SRP) Programme Editors: Salim Mohamed Nasir and M Nirmala Copyright © 2015 ISBN: 978-981-09-4915-0 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University. Printed by Future Print Pte Ltd 10 Kaki Bukit Road 1,#01-35 KB Industrial Building, Singapore 416175 Tel: 6842 5500 Email: [email protected] Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies (SRP) Programme S Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University Block S4, Level B4, Nanyang Avenue, Singapore 639798 Tel: (65) 6592 1680 Email: [email protected] Website: www.rsis.edu.sg A PRECIOUS RELIGIOUS TREASURE PEACE RELIGIOUS PEACE, RELIGIOUS PEACE Contents A PRECIOUS TREASURE A Precious Treasure 05 Message by PM Lee Hsien Loong 07 Foreword INTRODUCTION 10 About SRP 13 Profiles 22 Reclaiming Our Common Humanity - Role of Religion amidst Pluralism 32 Theological and Cultural Foundations for Strong and Positive Inter-Religious Relations 42 Theological and Cultural Foundations for an Inclusivist View of the Religious ‘Other’ in Islamic Tradition 60 Inter-Religious Relations in Singapore 76 Hinduism, Peace-building and the Religious ‘Other’ 91 Annexes 112 Acknowledgements RELIGIOUS RELIGIOUS PEACE, PEACE A PRECIOUS TREASURE RELIGIOUS PEACE, A PRECIOUS TREASURE 03 Meeting with Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. (MCI photo by Terence Tan) Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong met Sheikh Dr Ali Gomaa and Most Rev Dr Mouneer Hanna Anis at the Istana on 6 June 2014. -

Senarai Buku-Buku Inggeris Yang Lulus

SENARAI BUKU-BUKU INGGERIS YANG LULUS Tarikh dikemaskini: 19/04/2017 * Bagi penguna windows sila tekan ctrl+f untuk carian BIL TAJUK BUKU PENGARANG PENERBIT CETAKAN KEPUTUSAN ISBN RUJUKAN 1 ANSWERS TO NON-MUSLIMS' COMMON QUESTIONS DR. ZAKIR NAIK IDCI. ISLAMIC DAWAH Apr-10 LULUS - 63 ABOUT ISLAM CENTRE INTERNATIONAL (DAFTAR 01) 2 7 FORMULAS OF EXCELLENT INDIVIDUALS DR. DANIAL ZAINAL ABIDIN PTS MILLENNIA SDN BHD 2010 LULUS ISBN : 978-967-5564- 145 47-5 3 A QUALITIES OF A GOOD MUSLIM WIFE TAIWO HAMBAL ABDUL A.S. NOORDEEN 2001 LULUS - 39 RAHEEM (DAFTAR 01) 4 ISLAMIC MEDICINE THE KEY TO A BETTER LIFE YUSUF AL- HAJJ AHMAD MAKTABA DAR-US-SALAM 2010 LULUS ISBN: 978-603-500- 195 061-1 5 TRUE WISDOM DESCRIBED IN THE QUR'AN HARUN YAHYA GOODWORD BOOKS 2004 LULUS - 208 (DAFTAR 01) 6 1001 INVENTIONS MUSLIM HERIGATE IN OUR WORLD - FOUNDATION FOR 2007 LULUS TANPA ISBN:9780955242618 4 SECOND EDITION SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY (2nd COP (DAFTAR 01) 7 15 WAYS TO INCREASE YOUR EARNINGS FROM THE ABU AMMAR YASIR QADHI AL-HIDAYAH 2002 LULUS ISBN: 1-898649-56-1 56 QUR'AN AND SUNNAH PUBLISHING & DISTRIBUTION 8 200 FAQ ON ISLAMIC ISLAMIC BELIEFS AL-HAFIZ AL-HAKIMI DAR AL-MANARAH 2001 LULUS - 256 (DAFTAR 01) 9 24 HOURS IN THE LIFE OF A MUSLIM HARUN YAHYA TA-HA PUBLISHERS LTD. _ LULUS - 264 (DAFTAR 01) 10 300 AUTHENTICATED MIRACLES OF MUHAMMAD BADR AZIMABADI ADAM PUBLISHERS & 2000 LULUS - 269 DISTRIBUTORS (DAFTAR 01) 11 365 DAYS WITH THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD NURDAN DAMLA GOODWORK BOOKS 2014 LULUS ISBN 978-81-7898- 241 852-8 12 50 BIG IDEAS YOU REALLY NEED TO KNOW BEN DUPRE QUERCUS _ LULUS TANPA - 27 COP (DAFTAR 01) 13 8 PRODUCTIVE RAMADAN EASY STEPS TO FINISH - ISLAMIA, THE BRUNEI - LULUS - 53 QURAN THIS RAMADHAN TIMES 14 8 STEP TO HELP PREPARE FOR RAMADHAN - ISLAMIA, THE BRUNEI 2013 LULUS - 54 TIMES Hak Cipta Terpelihara Bahagian Penapisan dan Pameran, Pusat Da'wah Islamiah, Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama, Negara Brunei Darussalam 15 A BOOK ABOUT COLORS ALLAH IS AL KHALIQ (THE SABA GHAZI AMEEN IQRA' INTERNATIONAL 2002 LULUS TANPA - 120 CREATOR) EDUCATION COP 16 A BOY FROM MAKKAH DR.