Sharing Translations Or Supporting Terror? an Analysis of Tarek Mehanna in the Aftermath of Holder V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018

Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Clifford FEBRUARY 2018 THE TRAVELERS American Jihadists in Syria and Iraq BY Alexander Meleagrou-Hitchens, Seamus Hughes, Bennett Cliford Program on Extremism February 2018 All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2018 by Program on Extremism Program on Extremism 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, DC 20006 www.extremism.gwu.edu Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................v A Note from the Director .........................................................................................vii Foreword ......................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary .......................................................................................................1 Introduction: American Jihadist Travelers ..........................................................5 Foreign Fighters and Travelers to Transnational Conflicts: Incentives, Motivations, and Destinations ............................................................. 5 American Jihadist Travelers: 1980-2011 ..................................................................... 6 How Do American Jihadist -

Notes on a Terrorism Trial •Fi Preventive Prosecution, Â

Notes on a Terrorism Trial – Preventive Prosecution, “Material Support” and The Role of The Judge after United States v. Mehanna George D. Brown* Abstract The terrorism trial of Tarek Mehanna, primarily for charges of providing “material support” to terrorism, presented elements of a preventive prosecution as well as the problem of applying Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project (HLP) to terrorism‐related speech. This Article examines both aspects of the case, with emphasis on the central role of the trial judge. As criminal activity becomes more amorphous, the jury looks to the judge for guidance. His rulings on potentially prejudicial evidence which may show just how much of a “terrorist” the defendant is are the key aspect of this guidance. If the defendant is found guilty, the sentence imposed by the judge can have a profound impact on future preventive prosecutions. Particularly important is the judge’s handling of the Sentencing Guidelines’ “Terrorism Enhancement.” As for speech issues, there is enough ambiguity in HLP to let lower courts formulate and apply its test differently. HLP emphasizes co‐ordination with a foreign terrorist organization before speech can be criminalized. There is now movement toward a concept of one‐way coordination that can turn speech prosecutions into a form of general prevention of potential terrorists. All of these issues were central to Mehanna. The Article’s analysis of how the trial court handled them is meant to increase understanding of them, and to highlight the central role of the judge. I. Introduction -

The Suffocation of Free Speech Under the Gravity of Danger of Terrorism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by bepress Legal Repository First Amendment Tim Davis Prof. Raskin The Suffocation of Free Speech under the Gravity of Danger of Terrorism I. Introduction Ali al -Timimi (“al- Timimi”) is an outspoken Muslim scholar who is well respected in the worldwide Muslim community. In his fervent support of Muslims everywhere, he has openly proclaimed that America is one of the chief enemies of the Muslim populace. 1 He has proclaimed that the explosion of the space shuttle Columbia was a sign for Muslims to take action.2 He has urged young Muslim men to jihad, to wage armed conflict with the enemies of Islam. 3 It is safe to say that al -Timimi has made numerous speeches that most Americans would find highly objectionable. On September 23, 2004, the Federal government charged al -Timimi with a six -co unt indictment4, which was later superceded by the present ten -count indictment. 5 During the trial in April 2005, the prosecution introduced over 250 evidentiary exhibits 6, testimony from several expert witnesses on radical Islamism 7, and testimony from various government agents. In 1 Presentencing Report for Muhammed Aatique at 17, United States v. Khan, (No. 03 -296 -A). 2 Presentencing Report for Muhammed Aatique at 17, United States v. Khan, (No. 03 -296 -A). 3 Transcripts, Rebuttal Argument by Mr. Kromberg, Pleading 123 at 14, United States v. Al -Timimi, (No. 1:04cr385). 4 Indictment, United States v. Al -Timimi, (No. 1:04cr385), available at http://www.altimimi.org. -

Wallace Roney Joe Fiedler Christopher

feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 YOUr FREE GUide TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM BILLY HART ENCHANCING wallace joe christopher eddie roney fiedler hollyday costa Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East feBrUARY 2019—ISSUe 202 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 new york@niGht 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: interview : wallace roney 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: artist featUre : joe fiedler 7 by steven loewy [email protected] General Inquiries: on the cover : Billy hart 8 by jim motavalli [email protected] Advertising: encore : christopher hollyday 10 by robert bush [email protected] Calendar: lest we forGet : eddie costa 10 by mark keresman [email protected] VOXNews: LAbel spotliGht : astral spirits 11 by george grella [email protected] VOXNEWS by suzanne lorge US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or oBitUaries 12 by andrey henkin money order to the address above or email [email protected] FESTIVAL REPORT 13 Staff Writers Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, Robert Bush, Kevin Canfield, CD reviews 14 Marco Cangiano, Thomas Conrad, Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Miscellany Tom Greenland, George Grella, 31 Anders Griffen, Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, event calendar Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, 32 Marilyn Lester, Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Jim Motavalli, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Brian Charette, Steven Loewy, As unpredictable as the flow of a jazz improvisation is the path that musicians ‘take’ (the verb Francesco Martinelli, Annie Murnighan, implies agency, which is sometimes not the case) during the course of a career. -

National Security Case Studies Special

National Security Case Studies Special Case-Management Challenges Robert Timothy Reagan Federal Judicial Center June 25, 2013 This Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to develop and conduct research and education programs for the judicial branch. While the Center regards the content as responsible and valuable, it does not reflect policy or recommendations of the Board of the Federal Judicial Center. Contents Table of Challenges .......................................................................................................... xi Table of Judges ............................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 2 TERRORISM PROSECUTIONS ..................................................................................... 3 First World Trade Center Bombing United States v. Salameh (Kevin Thomas Duffy) and United States v. Abdel Rahman (Michael B. Mukasey) (S.D.N.Y.) ....................................................................... 5 Challenge: Interpreters ............................................................................................. 24 Challenge: Court Security ......................................................................................... 24 Challenge: Pro Se Defendants ................................................................................. 24 Challenge: Jury -

Mehanna Government Brief

Case: 12-1461 Document: 00116514022 Page: 1 Date Filed: 04/08/2013 Entry ID: 5724362 NO. 12-1461 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT __________ UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLEE V. TAREK MEHANNA, APPELLANT __________ ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS __________ BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES __________ CARMEN M. ORTIZ MYTHILI RAMAN United States Attorney Acting Assistant Attorney General District of Massachusetts Criminal Division JOHN P. CARLIN DENIS J. MCINERNEY Acting Assistant Attorney Acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General General Criminal Division National Security Division ELIZABETH D. COLLERY JOSEPH F. PALMER Attorney, Appellate Section JEFFREY D. GROHARING Criminal Division Attorneys U.S. Department of Justice National Security Division 950 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Room 1264 Washington, DC 20530 (202) 353-3891 [email protected] Case: 12-1461 Document: 00116514022 Page: 2 Date Filed: 04/08/2013 Entry ID: 5724362 TABLE OF CONTENTS JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT. ........................................................................ 1 STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES. ............................................................................ 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE................................................................................. 3 STATEMENT OF FACTS. ...................................................................................... 6 1. Overview. ............................................................................................. 6 2. Mehanna -

Opening Brief

Case: 12-1461 Document: 00116470099 Page: 1 Date Filed: 12/17/2012 Entry ID: 5698298 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT No. 12-1461 Tarek Mehanna, Defendant-Appellant, v. United States of America, Appellee. ON APPEAL FROM A JUDGMENT OF THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT TAREK MEHANNA Sabin Willett, No. 18725 J. W. Carney, Jr., No. 40016 Susan Baker Manning, No. 1152545 CARNEY & BASSIL Julie Silva Palmer, No. 1140407 20 Park Plaza, Suite 1405 BINGHAM McCUTCHEN LLP Boston, MA 02116 One Federal Street 617.338.5566 Boston, Massachusetts 02110-1726 617.951.8000 Case: 12-1461 Document: 00116470099 Page: 2 Date Filed: 12/17/2012 Entry ID: 5698298 TABLE OF CONTENTS REASONS WHY ORAL ARGUMENT SHOULD BE HEARD ........................... xi JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT ......................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF ISSUES ...................................................................................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................................................. 3 STATEMENT OF FACTS ....................................................................................... 7 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............................................................................. 19 ARGUMENT .......................................................................................................... 21 I. STANDARD OF REVIEW ......................................................................... -

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Appeal: 06-4997 Doc: 71 Filed: 01/23/2008 Pg: 1 of 14 PUBLISHED UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. No. 06-4997 ALI ASAD CHANDIA, a/k/a Abu Qatada, Defendant-Appellant. Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia, at Alexandria. Claude M. Hilton, Senior District Judge. (1:05-cr-00401-CMH-1) Argued: October 30, 2007 Decided: January 23, 2008 Before MICHAEL, MOTZ, and KING, Circuit Judges. Affirmed in part, vacated in part, and remanded by published opinion. Judge Michael wrote the opinion, in which Judge Motz and Judge King joined. COUNSEL ARGUED: Marvin David Miller, Alexandria, Virginia, for Appel- lant. John T. Gibbs, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUS- TICE, Washington, D.C., for Appellee. ON BRIEF: Chuck Rosenberg, United States Attorney, David H. Laufman, Assistant United States Attorney, OFFICE OF THE UNITED STATES ATTORNEY, Alexandria, Virginia, for Appellee. Appeal: 06-4997 Doc: 71 Filed: 01/23/2008 Pg: 2 of 14 2 UNITED STATES v. CHANDIA OPINION MICHAEL, Circuit Judge: Ali Asad Chandia appeals from his conviction, after a jury trial, on three counts of providing material support to terrorists or terrorist organizations. See 18 U.S.C. §§ 2339A, 2339B. Chandia challenges his convictions on several grounds, although he does not contest the sufficiency of the evidence. He also argues that the district court erred in sentencing when it applied the terrorism enhancement under U.S.S.G. §3A1.4. We affirm Chandia’s convictions but, because the district court failed to make the factual findings necessary to impose the §3A1.4 enhancement, we vacate the sentence and remand for resentencing. -

Ohio Terrorism N=30

Terry Oroszi, MS, EdD Advanced Technical Intelligence Center ABC Boonshoft School of Medicine, WSU Henry Jackson Foundation, WPAFB The Dayton Think Tank, Dayton, OH Definitions of Terrorism International Terrorism Domestic Terrorism Terrorism “use or threatened use of “violent acts that are “the intent to instill fear, and violence to intimidate a dangerous to human life the goals of the terrorists population or government and and violate federal or state are political, religious, or thereby effect political, laws” ideological” religious, or ideological change” “Political, Religious, or Ideological Goals” The Research… #520 Charged (2001-2018) • Betim Kaziu • Abid Naseer • Ali Mohamed Bagegni • Bilal Abood • Adam Raishani (Saddam Mohamed Raishani) • Ali Muhammad Brown • Bilal Mazloum • Adam Dandach • Ali Saleh • Bonnell (Buster) Hughes • Adam Gadahn (Azzam al-Amriki) • Ali Shukri Amin • Brandon L. Baxter • Adam Lynn Cunningham • Allen Walter lyon (Hammad Abdur- • Brian Neal Vinas • Adam Nauveed Hayat Raheem) • Brother of Mohammed Hamzah Khan • Adam Shafi • Alton Nolen (Jah'Keem Yisrael) • Bruce Edwards Ivins • Adel Daoud • Alwar Pouryan • Burhan Hassan • Adis Medunjanin • Aman Hassan Yemer • Burson Augustin • Adnan Abdihamid Farah • Amer Sinan Alhaggagi • Byron Williams • Ahmad Abousamra • Amera Akl • Cabdulaahi Ahmed Faarax • Ahmad Hussam Al Din Fayeq Abdul Aziz (Abu Bakr • Amiir Farouk Ibrahim • Carlos Eduardo Almonte Alsinawi) • Amina Farah Ali • Carlos Leon Bledsoe • Ahmad Khan Rahami • Amr I. Elgindy (Anthony Elgindy) • Cary Lee Ogborn • Ahmed Abdel Sattar • Andrew Joseph III Stack • Casey Charles Spain • Ahmed Abdullah Minni • Anes Subasic • Castelli Marie • Ahmed Ali Omar • Anthony M. Hayne • Cedric Carpenter • Ahmed Hassan Al-Uqaily • Antonio Martinez (Muhammad Hussain) • Charles Bishop • Ahmed Hussein Mahamud • Anwar Awlaki • Christopher Lee Cornell • Ahmed Ibrahim Bilal • Arafat M. -

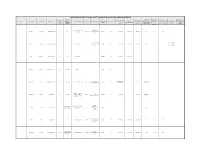

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11

DOJ Public/Unsealed Terrorism and Terrorism-Related Convictions 9/11/01-12/31/14 Date of Initial Terrorist Country or If Parents Are Defendant's Immigration Status If a U.S. Citizen, Entry or Immigration Status Current Organization Conviction Current Territory of Origin, Citizens, Natural- Number Charge Date Conviction Date Defendant Age at Conviction Offenses Sentence Date Sentence Imposed Last U.S. Residence at Time of Natural-Born or Admission to at Time of Initial Immigration Status Affiliation or District Immigration Status If Not a Natural- Born or Conviction Conviction Naturalized? U.S., If Entry or Admission of Parents Inspiration Born U.S. Citizen Naturalized? Applicable 243 months 18/2339B; 18/922(g)(1); 1 5/27/2014 10/30/2014 Donald Ray Morgan 44 ISIS 5/13/15 imprisonment; 3 years MDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Natural-Born N/A N/A N/A 18/924(a)(2) SR 3 years imprisonment; Unknown. Mother 2 8/29/2013 10/28/2014 Robel Kidane Phillipos 19 2x 18/1001(a)(2) 6/5/15 3 years SR; $25,000 DMA MA U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen Naturalized Ethiopia came as a refugee fine from Ethiopia. 3 4/1/2014 10/16/2014 Akba Jihad Jordan 22 ISIS 18/2339A EDNC NC U.S. Citizen U.S. Citizen 4 9/24/2014 10/3/2014 Mahdi Hussein Furreh 31 Al-Shabaab 18/1001 DMN MN 25 years Lawful Permanent 5 11/28/2012 9/25/2014 Ralph Kenneth Deleon 26 Al-Qaeda 18/2339A; 18/956; 18/1117 2/23/15 CDCA CA N/A Philippines imprisonment; life SR Resident 18/2339A; 18/2339B; 25 years 6 12/12/2012 9/25/2014 Sohiel Kabir 37 Al-Qaeda 18/371 (1812339D 2/23/15 CDCA CA U.S. -

Expert Report: U.S. V. Hassan Abu Jihaad

Expert Report: U.S. v. Hassan Abu Jihaad Evan F. Kohlmann ([email protected]) August 2007 INTRODUCTION My full name is Evan Francois Kohlmann. I am an International Terrorism Consultant who specializes in tracking Al-Qaida and other contemporary terrorist movements. I hold a degree in International Politics from the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service (Georgetown University), and a Juris Doctor (professional law degree) from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. I am also the recipient of a certificate in Islamic studies from the Prince Alwaleed bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding (CMCU) at Georgetown University. I currently work as an investigator with the Nine Eleven Finding Answers (NEFA) Foundation and as an on-air analyst for NBC News in the United States. I also run an Internet website Globalterroralert.com that provides information to the general public relating to international terrorism. I am author of the book Al-Qaida’s Jihad in Europe: the Afghan-Bosnian Network (Berg/Oxford International Press, London, 2004) which has been used as a teaching text in graduate- level terrorism courses offered at such educational institutions as Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government and the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). As part of my research beginning in approximately 1997, I have traveled overseas to interview known terrorist recruiters and organizers (such as Abu Hamza al-Masri) and to attend underground conferences and rallies; I have reviewed thousands of open source documents; and, I have amassed one of the largest digital collections of terrorist multimedia and propaganda in the world. -

Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Anti-Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans Author: David Schanzer, Charles Kurzman, Ebrahim Moosa Document No.: 229868 Date Received: March 2010 Award Number: 2007-IJ-CX-0008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Anti- Terror Lessons of Muslim-Americans DAVID SCHANZER SANFORD SCHOOL OF PUBLIC POLICY DUKE UNIVERSITY CHARLES KURZMAN DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL EBRAHIM MOOSA DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION DUKE UNIVERSITY JANUARY 6, 2010 This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Project Supported by the National Institute of Justice This project was supported by grant no.