Movement Patterns and Genetic Stock Delineation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TNP SOK 2011 Internet

GARDEN ROUTE NATIONAL PARK : THE TSITSIKAMMA SANP ARKS SECTION STATE OF KNOWLEDGE Contributors: N. Hanekom 1, R.M. Randall 1, D. Bower, A. Riley 2 and N. Kruger 1 1 SANParks Scientific Services, Garden Route (Rondevlei Office), PO Box 176, Sedgefield, 6573 2 Knysna National Lakes Area, P.O. Box 314, Knysna, 6570 Most recent update: 10 May 2012 Disclaimer This report has been produced by SANParks to summarise information available on a specific conservation area. Production of the report, in either hard copy or electronic format, does not signify that: the referenced information necessarily reflect the views and policies of SANParks; the referenced information is either correct or accurate; SANParks retains copies of the referenced documents; SANParks will provide second parties with copies of the referenced documents. This standpoint has the premise that (i) reproduction of copywrited material is illegal, (ii) copying of unpublished reports and data produced by an external scientist without the author’s permission is unethical, and (iii) dissemination of unreviewed data or draft documentation is potentially misleading and hence illogical. This report should be cited as: Hanekom N., Randall R.M., Bower, D., Riley, A. & Kruger, N. 2012. Garden Route National Park: The Tsitsikamma Section – State of Knowledge. South African National Parks. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................2 2. ACCOUNT OF AREA........................................................................................................2 -

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Speciestm

Species 2014 Annual ReportSpecies the Species of 2014 Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme Species ISSUE 56 2014 Annual Report of the Species Survival Commission and the Global Species Programme • 2014 Spotlight on High-level Interventions IUCN SSC • IUCN Red List at 50 • Specialist Group Reports Ethiopian Wolf (Canis simensis), Endangered. © Martin Harvey Muhammad Yazid Muhammad © Amazing Species: Bleeding Toad The Bleeding Toad, Leptophryne cruentata, is listed as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesTM. It is endemic to West Java, Indonesia, specifically around Mount Gede, Mount Pangaro and south of Sukabumi. The Bleeding Toad’s scientific name, cruentata, is from the Latin word meaning “bleeding” because of the frog’s overall reddish-purple appearance and blood-red and yellow marbling on its back. Geographical range The population declined drastically after the eruption of Mount Galunggung in 1987. It is Knowledge believed that other declining factors may be habitat alteration, loss, and fragmentation. Experts Although the lethal chytrid fungus, responsible for devastating declines (and possible Get Involved extinctions) in amphibian populations globally, has not been recorded in this area, the sudden decline in a creekside population is reminiscent of declines in similar amphibian species due to the presence of this pathogen. Only one individual Bleeding Toad was sighted from 1990 to 2003. Part of the range of Bleeding Toad is located in Gunung Gede Pangrango National Park. Future conservation actions should include population surveys and possible captive breeding plans. The production of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is made possible through the IUCN Red List Partnership. -

Geographic Structure of European Anchovy: a Nuclear-DNA Study Yanis Bouchenak-Khelladi, Jean-Dominique Durand, Antonios Magoulas, Philippe Borsa

Geographic structure of European anchovy: a nuclear-DNA study Yanis Bouchenak-Khelladi, Jean-Dominique Durand, Antonios Magoulas, Philippe Borsa To cite this version: Yanis Bouchenak-Khelladi, Jean-Dominique Durand, Antonios Magoulas, Philippe Borsa. Geographic structure of European anchovy: a nuclear-DNA study. Journal of Sea Research (JSR), Elsevier, 2008, 59, pp.269-278. 10.1016/j.seares.2008.03.001. hal-00553681 HAL Id: hal-00553681 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00553681 Submitted on 8 Jan 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. To be cited as: Bouchenak-Khelladi Y., Durand J.-D., Magoulas A., Borsa P. 2008. – Geographic structure of European anchovy: a nuclear-DNA study. Journal of Sea Research 59, 269-278 [doi:10.1016/j.seares.2008.03.001] Geographic structure of European anchovy: a nuclear-DNA study Yanis Bouchenak-Khelladi a, Jean-Dominique Durand b, Antonios Magoulas c, Philippe Borsa d,* a Department of Botany, Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland b Institut de recherche pour le développement, Dakar, Senegal c Institute -

Worse Things Happen at Sea: the Welfare of Wild-Caught Fish

[ “One of the sayings of the Holy Prophet Muhammad(s) tells us: ‘If you must kill, kill without torture’” (Animals in Islam, 2010) Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish Alison Mood fishcount.org.uk 2010 Acknowledgments Many thanks to Phil Brooke and Heather Pickett for reviewing this document. Phil also helped to devise the strategy presented in this report and wrote the final chapter. Cover photo credit: OAR/National Undersea Research Program (NURP). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Dept of Commerce. 1 Contents Executive summary 4 Section 1: Introduction to fish welfare in commercial fishing 10 10 1 Introduction 2 Scope of this report 12 3 Fish are sentient beings 14 4 Summary of key welfare issues in commercial fishing 24 Section 2: Major fishing methods and their impact on animal welfare 25 25 5 Introduction to animal welfare aspects of fish capture 6 Trawling 26 7 Purse seining 32 8 Gill nets, tangle nets and trammel nets 40 9 Rod & line and hand line fishing 44 10 Trolling 47 11 Pole & line fishing 49 12 Long line fishing 52 13 Trapping 55 14 Harpooning 57 15 Use of live bait fish in fish capture 58 16 Summary of improving welfare during capture & landing 60 Section 3: Welfare of fish after capture 66 66 17 Processing of fish alive on landing 18 Introducing humane slaughter for wild-catch fish 68 Section 4: Reducing welfare impact by reducing numbers 70 70 19 How many fish are caught each year? 20 Reducing suffering by reducing numbers caught 73 Section 5: Towards more humane fishing 81 81 21 Better welfare improves fish quality 22 Key roles for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 84 23 Strategies for improving welfare of wild-caught fish 105 Glossary 108 Worse things happen at sea: the welfare of wild-caught fish 2 References 114 Appendix A 125 fishcount.org.uk 3 Executive summary Executive Summary 1 Introduction Perhaps the most inhumane practice of all is the use of small bait fish that are impaled alive on There is increasing scientific acceptance that fish hooks, as bait for fish such as tuna. -

Pcr-Based Dgge Identification of Bacteria and Yeasts

ESTABLISHMENT OF A GENETIC DATABASE AND MOLECULAR METHODS FOR THE IDENTIFICATION OF FISH SPECIES AVAILBLE ON THE SOUTH AFRICAN MARKET DONNA-MAREÈ CAWTHORN Dissertation presented for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (FOOD SCIENCE) in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Promotor: Prof. R.C. Witthuhn Co-promotor: Dr. H.A. Steinman December 2011 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. 08 November 2011 _________________________ ___________________ Donna-Mareè Cawthorn Date Copyright © 2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za iii ABSTRACT Consumers have the right to accurate information on the fish products they purchase to enable them to make educated seafood selections that will not endanger their own wellbeing or the wellbeing of the environment. Unfortunately, marine resource scarcity, financial incentives and inadequate or poorly enforced regulations have all promoted the mislabelling of fish species on global markets, the results of which may hold economic, conservation and health consequences. The primary aims of this study were to determine the most commonly available fish species on the South African market, to establish and compare DNA-based methods for the unambiguous identification of these species and to utilise the most applicable methods to evaluate the extent of mislabelling on the local fisheries market. -

Larval Fish Dynamics in Coastal and Oceanic

LARVAL FISH DYNAMICS IN COASTAL AND OCEANIC HABITATS IN THE CANARY CURRENT LARGE MARINE ECOSYSTEM (12 – 23°N) Dissertation with the aim of achieving a doctoral degree at the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences Department of Biology of University Hamburg submitted by Maik Tiedemann M.Sc. Marine Biology B.Sc. Biology Hamburg, 2017 The present cumulative thesis is based on the scope on the bylaws of the Department of Biology's Doctoral Committee supplementing the Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences Doctoral Degree Regulations dated 1 December 2010 including adopted bylaws dated 23 February 2016. The content of chapter III may have changed in the process of publication and the submission of the present thesis. Please contact the principal author for citation purposes. Day of submission: 17. August 2017 Day of oral examination: 01. December 2017 The following evaluators recommend the admission of the dissertation: 1. Evaluator: Prof. Dr. Christian Möllmann Institute for Hydrobiology and Fisheries Science, Center for Earth System Research and Sustainability (CEN), Klima Campus, University of Hamburg, Grosse Elbstrasse 133, D-22767 Hamburg, Germany 2. Evaluator: Dr. Heino O. Fock Thünen-Institute (TI), Institute of Sea Fisheries, Federal Research Institute for Rural Areas, Forestry and Fisheries, Palmaille 9, 22767 Hamburg, Germany PREFACE The present dissertation cumulates the results of my doctoral project conducted from April 2013 to July 2017. My project was part of the tripartite German – French – African project “Ecosystem approach to the management of fisheries and the marine environment in West African waters” (AWA) funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the grant number 01DG12073A. -

Proefschrift Muller

University of Groningen The commuting parent Mullers, Ralf Hubertus Elisabeth IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2009 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Mullers, R. H. E. (2009). The commuting parent: Energetic constraints in a long distance forager, the Cape gannet. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 05-10-2021 The commuting parent Energetic constraints in a long distance forager, the Cape gannet The research reported in this thesis was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Foundation for the Advancement of Tropical Research (WOTRO) of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). -

Shallow Population Histories in Deep Evolutionary Lineages of Marine Fishes: Insights from Sardines and Anchovies and Lessons for Conservation

Shallow Population Histories in Deep Evolutionary Lineages of Marine Fishes: Insights From Sardines and Anchovies and Lessons for Conservation W. S. Grant and B. W. Bowen Most surveys of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) in marine ®shes reveal low levels of sequence divergence between haplotypes relative to the differentiation observed between sister taxa. It is unclear whether this pattern is due to rapid lineage sorting accelerated by sweepstakes recruitment, historical bottlenecks in population size, founder events, or natural selection, any of which could retard the accumulation of deep mtDNA lineages. Recent advances in paleoclimate research prompt a re- examination of oceanographic processes as a fundamental in¯uence on genetic diversity; evidence from ice cores and anaerobic marine sediments document strong regime shifts in the world's oceans in concert with periodic climatic changes. These changes in sea surface temperatures, current pathways, upwelling intensities, and retention eddies are likely harbingers of severe ¯uctuations in pop- ulation size or regional extinctions. Sardines (Sardina, Sardinops) and anchovies (Engraulis) are used to assess the consequences of such oceanographic process- es on marine ®sh intrageneric gene genealogies. Representatives of these two groups occur in temperate boundary currents on a global scale, and these regional populations are known to ¯uctuate markedly. Biogeographic and genetic data in- dicate that Sardinops has persisted for at least 20 million years, yet the mtDNA genealogy for this group coalesces in less than half a million years and points to a recent founding of populations around the rim of the Indian±Paci®c Ocean. Phy- logeographic analysis of Old World anchovies reveals a Pleistocene dispersal from the Paci®c to the Atlantic, almost certainly via southern Africa, followed by a very recent recolonization from Europe to southern Africa. -

Liste Espèces

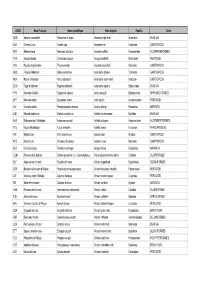

CODE Nom Français Nom scientifique Nom Anglais Famille Ordre ODQ Anomie cascabelle Pododesmus cepio Abalone jingle shell Anomiidae BIVALVIA ABX Ormeaux nca Haliotis spp Abalones nei Haliotidae GASTROPODA REN Sébaste rose Sebastes fasciatus Acadian redfish Scorpaenidae SCORPAENIFORMES YNA Acoupa toeroe Cynoscion acoupa Acoupa weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI HSV Pourpre aiguillonnee Thais aculeata Aculeate rock shell Muricidae GASTROPODA GBQ Troque d'Adanson Gibbula adansoni Adanson's gibbula Trochidae GASTROPODA NKA Natice d'Adanson Natica adansoni Adanson's moon snail Naticidae GASTROPODA GLW Tagal d'Adanson Tagelus adansonii Adanson's tagelus Solecurtidae BIVALVIA PYD Manchot d'Adélie Pygoscelis adeliae Adelie penguin Spheniscidae SPHENISCIFORMES QFT Maconde aden Synagrops adeni Aden splitfin Acropomatidae PERCOIDEI NIV Crevette adonis Parapenaeopsis venusta Adonis shrimp Penaeidae NATANTIA DJD Modiole adriatique Modiolus adriaticus Adriatic horse mussel Mytilidae BIVALVIA AAA Esturgeon de l'Adriatique Acipenser naccarii Adriatic sturgeon Acipenseridae ACIPENSERIFORMES FCV Fucus d'Adriatique Fucus virsoides Adriatic wrack Fucaceae PHAEOPHYCEAE IRR Mitre brûlée Mitra eremitarum Adusta miter Mitridae GASTROPODA KCE Murex bruni Chicoreus brunneus Adusta murex Muricidae GASTROPODA AES Crevette ésope Pandalus montagui Aesop shrimp Pandalidae NATANTIA CGM Poisson-chat, hybride Clarias gariepinus x C. macrocephalus Africa-bighead catfish, hybrid Clariidae SILURIFORMES SUF Ange de mer africain Squatina africana African angelshark Squatinidae SQUALIFORMES -

Global Seafood Production from Mariculture: Current Status, Trends and Its Future Under Climate Change

GLOBAL SEAFOOD PRODUCTION FROM MARICULTURE: CURRENT STATUS, TRENDS AND ITS FUTURE UNDER CLIMATE CHANGE by Muhammed Alolade Oyinlola B. AQFM., University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria, 2010 M.Sc., Universität Bremen, Germany, 2014 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Zoology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2019 © Muhammed Alolade Oyinlola, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Global seafood production from mariculture: current status, trends and its future under climate change submitted by Muhammed Alolade Oyinlola in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology Examining Committee: Dr. William Wai Lung Cheung Supervisor Dr. Daniel Pauly Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Evgeny Pakhomov University Examiner Dr. Xiaonan Lu University Examiner Additional Supervisory Committee Members: Dr. Rashid Sumaila Supervisory Committee Member Dr. Max Troell Supervisory Committee Member ii Abstract Mariculture is growing rapidly over the last three decades at an average rate of about 3.7% per year from 2001 to 2010. However, questions about mariculture sustainable development are uncertain because of diverse environmental challenges and concerns that the sector faces. Changing ocean conditions such as temperature, acidity, oxygen level and primary production can affect mariculture production, directly and indirectly, particularly the open and semi-open ocean farming operations. This dissertation aims to understand climate change impact on future seafood production from mariculture. Firstly, I update the existing Global Mariculture Database (GMD) with recent mariculture production and create a farm-gate price database to match the production data. -

Review of the State of World Marine Fishery Resources

ISSN 2070-7010 569 FAO FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL PAPER 569 Review of the state of world marine fishery resources Review of the state world marine fishery resources This publication presents an updated assessment and review of the current status of the world’s marine fishery resources. It summarizes the information available for each FAO Statistical Areas; discusses the major trends and changes that have occurred with the main fishery resources exploited in each area; and reviews the stock assessment work undertaken in support of fisheries management in each region. The review is based mainly on official catch statistics up until 2009 and relevant stock assessment and other complementary information available until 2010. It aims to provide the FAO Committee on Fisheries and, more generally, policy-makers, civil society, fishers and managers of world fishery resources with a comprehensive, objective and global review of the state of the living marine resources. ISBN 978-92-5-107023-9 ISSN 2070-7010 FAO 9 789251 070239 I2389E/1/12.11 Cover illustration: Emanuela D’Antoni FAO FISHERIES AND Review of the state AQUACULTURE TECHNICAL of world marine PAPER fishery resources 569 Marine and Inland Fisheries Service Fisheries and Aquaculture Resources Use and Conservation Division FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2011 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Multidisciplinary Investigation Into Stock Structure of Small Pelagic Fishes in Southern Africa

Multidisciplinary investigation into stock structure of small pelagic fishes in southern Africa S. L. Hampton Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Biological Sciences UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN August 2014 Univeristy of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Multidisciplinary investigation into stock structure of small pelagic fishes in southern Africa S. L. Hampton August 2014 Supervisors: Coleen Moloney (Ma-Re, University of Cape Town) Paulette Bloomer (MEEP, University of Pretoria) Carl van der Lingen (DAFF) The financial assistance of the National Research Foundation (NRF) towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. Declaration I know the meaning of Plagiarism and declare that all the work presented in this thesis is my own, except where it is properly acknowledged in the text. This thesis has not been submitted in whole or in part for a degree at another university. S.L. Hampton 15 August 2014 Multidisciplinary investigation into stock structure of small pelagic fishes in southern Africa Table of Contents Pages Acknowledgements i-iii Abstract 1 Chapter 1: An introduction to small pelagic fish and stock identification in southern Africa.