The Albani Psalter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introitus: the Entrance Chant of the Mass in the Roman Rite

Introitus: The Entrance Chant of the mass in the Roman Rite The Introit (introitus in Latin) is the proper chant which begins the Roman rite Mass. There is a unique introit with its own proper text for each Sunday and feast day of the Roman liturgy. The introit is essentially an antiphon or refrain sung by a choir, with psalm verses sung by one or more cantors or by the entire choir. Like all Gregorian chant, the introit is in Latin, sung in unison, and with texts from the Bible, predominantly from the Psalter. The introits are found in the chant book with all the Mass propers, the Graduale Romanum, which was published in 1974 for the liturgy as reformed by the Second Vatican Council. (Nearly all the introit chants are in the same place as before the reform.) Some other chant genres (e.g. the gradual) are formulaic, but the introits are not. Rather, each introit antiphon is a very unique composition with its own character. Tradition has claimed that Pope St. Gregory the Great (d.604) ordered and arranged all the chant propers, and Gregorian chant takes its very name from the great pope. But it seems likely that the proper antiphons including the introit were selected and set a bit later in the seventh century under one of Gregory’s successors. They were sung for papal liturgies by the pope’s choir, which consisted of deacons and choirboys. The melodies then spread from Rome northward throughout Europe by musical missionaries who knew all the melodies for the entire church year by heart. -

A Guide to Resources for SINGING and PRAYING the PSALMS

READ PRAY SING A Guide to Resources for SINGING and PRAYING the PSALMS – WELCOME – Voices of the Past on the Psalter We are delighted you have come to this conference, and I pray it has been helpful to you. Part of our aim is that you be encouraged and helped to make use of the Psalms in your own worship, using them as a guide for prayer and Dietrich Bonhoeffer singing. To that end we have prepared this booklet with some suggested “Whenever the Psalter is abandoned, an incomparable treasure vanishes from resources and an explanation of metrical psalms. the Christian church. With its recovery will come unsuspected power.” Special thanks are due to Michael Garrett who put this booklet together. We Charles Spurgeon have incorporated some material previously prepared by James Grant as well. “Time was when the Psalms were not only rehearsed in all the churches from day to day, but they were so universally sung that the common people As God has seen fit to give us a book of prayers and songs, and since he has knew them, even if they did not know the letters in which they were written. so richly blessed its use in the past, surely we do well to make every use of it Time was when bishops would ordain no man to the ministry unless he knew today. May your knowledge of God, your daily experience of him be deeply “David” from end to end, and could repeat each psalm correctly; even Councils enhanced as you use his words to teach you to speak to him. -

The Book of Psalms “Bless the Lord, O My Soul, and Forget Not All His Benefits” (103:2)

THE BOOK OF PSALMS “BLESS THE LORD, O MY SOUL, AND FORGET NOT ALL HIS BENEFITS” (103:2) BOOK I BOOK II BOOK III BOOK IV BOOK V 41 psalms 31 psalms 17 psalms 17 psalms 44 psalms 1 41 42 72 73 89 90 106 107 150 DOXOLOGY AT THESE VERSES CONCLUDES EACH BOOK 41:13 72:18-19 89:52 106:48 150:6 JEWISH TRADITION ASCRIBES TOPICAL LIKENESS TO PENTATEUCH GENESIS EXODUS LEVITICUS NUMBERS DEUTERONOMY ────AUTHORS ──── mainly mainly (or all) DAVID mainly mainly mainly DAVID and KORAH ASAPH ANONYMOUS DAVID BOOKS II AND III ADDED MISCELLANEOUS ORIGINAL GROUP BY DURING THE REIGNS OF COLLECTIONS DAVID HEZEKIAH AND JOSIAH COMPILED IN TIMES OF EZRA AND NEHEMIAH POSSIBLE CHRONOLOGICAL STAGES IN THE GROWTH AND COLLECTION OF THE PSALTER 1 The Book of Psalms I. Book Title The word psalms comes from the Greek word psalmoi. It suggests the idea of a “praise song,” as does the Hebrew word tehillim. It is related to a Hebrew concept which means “the plucking of strings.” It means a song to be sung to the accompaniment of stringed instruments. The Psalms is a collection of worship songs sung to God by the people of Israel with musical accompaniment. The collection of these 150 psalms into one book served as the first hymnbook for God’s people, written and compiled to assist them in their worship of God. At first, because of the wide variety of these songs, this praise book was unnamed, but eventually the ancient Hebrews called it “The Book of Praises,” or simply “Praises.” This title reflects its main purpose──to assist believers in the proper worship of God. -

The Phenomenon of Abstraction and Concretization

Abstraction and Concretization Of the Fruit of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil As Seen Through Biblical Interpretation and Art Alyssa Ovadis Department of Jewish Studies Faculty of Arts McGill University, Montreal April 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Alyssa Ovadis 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-68378-1 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-68378-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L’auteur conserve la propriété du droit d’auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protège cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

First and Second Degree Black Belt Training Manual

First and Second Degree Black Belt Training Manual Developed by: Adam J. Boisvert, A-5-19 Chief Instructor & Shannon L. Boisvert, A-3-31 Assistant Chief Instructor Black Belt: Expert or Novice One of the greatest misconceptions within the martial arts is the notion that all black belt holders are experts. It is understandable that those unacquainted with the martial arts might make this equation. However, students should certainly recognize that this is not always the case. Too often, novice black belt holders advertise themselves as experts and eventually even convince themselves. The black belt holder has usually learned enough technique to defend themselves against single opponents of average ability. They can be compared to a fledgling that has acquired enough feathers to leave the nest and fend for themselves. The first degree is a starting point. The student has merely built a foundation. The job of building the house lies ahead. The novice black belt holder will now really begin to learn technique. Now that they have mastered the alphabet, they can now begin to read. Years of hard work and study await them before they can even begin to consider themselves an instructor or expert. A good student will, at this stage, suddenly realize how very little they know. The black belt holder also enters a new era of responsibility. Though a freshman, they have entered a strong honorable fraternity of the black belt holders of the entire world; and their actions inside and outside the training hall will be carefully scrutinized. Their conduct will reflect on all black belt holders and they must constantly strive to set an example for all grade holders. -

“May the Divine Will Always Be Blessed!” Newsletter No

The Pious Universal Union for the Children of the Divine Will Official Newsletter for “The Pious Universal Union for Children of the Divine Will –USA” Come Supreme Will, down to reign in Your Kingdom on earth and in our hearts! ROGATE! FIAT ! “May the Divine Will always be blessed!” Newsletter No. 130 – March 4 A.D. 2013 “Now I die more content, because the Divine Volition consoled me more than usual with your presence in these lasts instants of my life. Now I see a long, beautiful and wide Road, illuminated by infinite and shining Suns... Oh, yes, I recognize them! They are the Suns of my acts done in the Divine Will. This is the road which I now must follow. It is the way prepared for me by the Divine Volition, it is the road of my triumph, it is the road of my glory, to connect me in the immense happiness of the Divine Will. It is my road, it is the road which I will reserve for you, dear Father; it is the road which I will reserve for all those souls who will want to live in the Divine Will.” 1 The Holy Death of Luisa Piccarreta By Padre Bernardino Bucci At the news of Luisa’s death which occurred on March 4 A.D. 1947, it seemed that the people of Corato paused to live a unique and extraordinary event. Their Luisa, their Saint, was no more. And like a river in full spate they poured into Luisa’s house to look at her and express their affection to her, for so many years esteemed and beloved by all. -

Fr. Luigi Villa: Probably John XXIII and Paul VI Initiated in the Freemasonry?

PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA PAUL VI… BEATIFIED? By father Doctor LUIGI VILLA (First Edition: February 1998 – in italian) (Second Edition: July 2001 –in italian) EDITRICE CIVILTà Via Galileo Galilei, 121 25123 BRESCIA (ITALY) PREFACE Paul VI was always an enigma to all, as Pope John XXIII did himself observe. But today, after his death, I believe that can no longer be said. In the light, in fact, of his numerous writings and speeches and of his actions, the figure of Paul VI is clear of any ambiguity. Even if corroborating it is not so easy or simple, he having been a very complex figure, both when speaking of his preferences, by way of suggestions and insinuations, and for his abrupt leaps from idea to idea, and when opting for Tradition, but then presently for novelty, and all in language often very inaccurate. It will suffice to read, for example, his Addresses of the General Audiences, to see a Paul VI prey of an irreducible duality of thought, a permanent conflict between his thought and that of the Church, which he was nonetheless to represent. Since his time at Milan, not a few called him already “ ‘the man of the utopias,’ an Archbishop in pursuit of illusions, generous dreams, yes, yet unreal!”… Which brings to mind what Pius X said of the Chiefs of the Sillon1: “… The exaltation of their sentiments, the blind goodness of their hearts, their philosophical mysticisms, mixed … with Illuminism, have carried them toward another Gospel, in which they thought they saw the true Gospel of our Savior…”2. -

Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections Through Hand Hygiene

infection control and hospital epidemiology august 2014, vol. 35, no. 8 shea/idsa practice recommendation Strategies to Prevent Healthcare-Associated Infections through Hand Hygiene Katherine Ellingson, PhD;1,a Janet P. Haas, PhD, RN, CIC;2,a Allison E. Aiello, PhD;3 Linda Kusek, MPH, RN, CIC;4 Lisa L. Maragakis, MD, MPH;5 Russell N. Olmsted, MPH, CIC;6 Eli Perencevich, MD, MS;7,8 Philip M. Polgreen, MD;7 Marin L. Schweizer, PhD;7,8 Polly Trexler, MS, CIC;5 Margaret VanAmringe, MHS;4 Deborah S. Yokoe, MD, MPH9 purpose ability to conveniently and comfortably sanitize hands at frequent intervals.8-10 Yet adherence to recommended hand Previously published guidelines provide comprehensive rec- hygiene practices remains low (approximately 40%), even 1,2 ommendations for hand hygiene in healthcare facilities. The in well-resourced facilities.11 Reasons for low hand hygiene intent of this document is to highlight practical recommen- adherence include inconvenient location of sinks, under- dations in a concise format, update recommendations with staffing or busy work setting, and skin irritation as well as the most current scientific evidence, and elucidate topics that cultural issues, such as lack of role models and inattention warrant clarification or more robust research. Additionally, to guidelines.12,13 this document is designed to assist healthcare facilities in II. Since publication of the Centers for Disease Control and implementing hand hygiene adherence improvement pro- Prevention (CDC) guidelines in 20021 and the World grams, including efforts to optimize hand hygiene product Health Organization (WHO) guidelines in 2009,2 hand use, monitor and report back hand hygiene adherence data, hygiene studies have been published that can inform var- and promote behavior change. -

A Folk Dance Program for Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Grades

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses 1959 A Folk Dance Program for Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Grades Alene Johnson Wesselius Central Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Educational Methods Commons, and the Elementary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Wesselius, Alene Johnson, "A Folk Dance Program for Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Grades" (1959). All Master's Theses. 234. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/234 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FOLK DANCE PROGRAM FOR FOURTH, FIFTH, AND SIXTH GRADES A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty Central Washington College of Education In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Education by Alene Johnson Wesselius August 1959 ;-' .l.._)'"'' ws15f SPECIAL I (COLLECTION c APPROVED FOR THE GRADUATE FACULTY Everett A. Irish, COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN Albert H. Poffenroth Donald J. Murphy ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Grateful acknowledgment is extended to Associate Pro fessor Dr. Everett A. Irish for his advice, friendly criticisms, and encouragement. The writer also wishes to recognize the assistance of Dr. Donald J. Murphy and Mr. A. H. Poffenroth. My appreciation goes, also, to the sixty-nine teachers who graciously accepted the responsibility of answering the questionnaire for this study. To Mr. Claude Brannan, Health, Safety, and Physical Education Consultant, Yakima Public Schools, Mr. -

Resource Guide 4

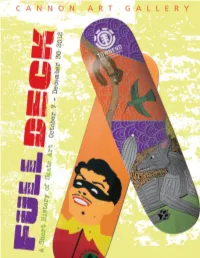

WILLIAM D. CANNON AR T G A L L E R Y TABLE OF CONTENTS Steps of the Three-Part-Art Gallery Education Program 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 Making the Most of Your Gallery Visit 5 The Artful Thinking Program 7 Curriculum Connections 8 About the Exhibition 10 About Street Skateboarding 11 Artist Bios 13 Pre-visit activities 33 Lesson One: Emphasizing Color 34 Post-visit activities 38 Lesson Two: Get Bold with Design 39 Lesson Three: Use Text 41 Classroom Extensions 43 Glossary 44 Appendix 53 2 STEPS OF THE THREE-PART-ART GALLERY EDUCATION PROGRAM Resource Guide: Classroom teachers will use the preliminary lessons with students provided in the Pre-Visit section of the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art resource guide. On return from your field trip to the Cannon Art Gallery the classroom teacher will use Post-Visit Activities to reinforce learning. The guide and exhibit images were adapted from the Full Deck: A Short History of Skate Art Exhibition Guide organized by: Bedford Gallery at the Lesher Center for the Arts, Walnut Creek, California. The resource guide and images are provided free of charge to all classes with a confirmed reservation and are also available on our website at www.carlsbadca.gov/arts. Gallery Visit: At the gallery, an artist educator will help the students critically view and investigate original art works. Students will recognize the differences between viewing copies and seeing works first and learn that visiting art galleries and museums can be fun and interesting. Hands-on Art Project: An artist educator will guide the students in a hands-on art project that relates to the exhibition. -

Carolyn Merchant the WOMEN, ECOLOGY, and the SCIENTIFIC

Carolyn Merchant THE OF AT WOMEN, ECOLOGY, AND THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION tfj 1817 Harper & Row, Publi$hers, San Francisco New York, Grand Rapids, Philadelphia, St. Louis London, Singapore, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto Acknowledgment is made fur the permission of the Journal of the History of Phi losophy to include a revised version of the author's article "The Vitalism of Anne Conway" (July 1979) in Chapter 11; of Ambix to include parts of the author's article "The Vitalism of Francis Mercury Van Helmont" (November 1979) in Chapters 4 and 11; of Indiana University Press. to reprint from Metamorphoses by Publius Ovid, translated by Rolfe Humphries (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1955); and of Cornell University Press to reprint tables on p. 312 from William E. Monter, Witchcraft in France and Switzerland. Copyright © 1976 by Cornell University. THE DEATH OF NATURE: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. Copyright © 1980 by Carolyn Merchant. PREFACE: 1990 copyright© 1989 by Carolyn Mer chant. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written per mission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Haroer & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022. FIRST HARPER & ROW PAPERBACK EDITION PUBLISHED IN 1983. Designed by Paul Quin Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Merchant, Carolyn. The death of nature. Originally published in 1980; with new preface. Includes bibliographical references. l . Women in science. 2. Philosophy of nature. 3. Human ecology. -

Special Collections Display

6 August: Special Collections display Hunterian Psalter England: c. 1170 MS Hunter 229 (U.3.2) One of a small group of elaborately illuminated twelfth century English psalters, this book is regarded as the greatest treasure of Dr William Hunter's magnificent eighteenth century library. Hunter acquired the manuscript in France amongst several other lots at the Jean-Louis Gaignat sale of 10 April 1769; he paid 50 livres and one sou for it - at the time, he was generally paying three times as much for early printed books. The identity of the undoubtedly wealthy patron who commissioned the manuscript's production is unknown, although it may possibly have been Roger de Mowbray (d.1188), from one of the greatest Anglo-Norman families of the twelfth century; having been a crusader, he had a knowledge of the sacred sites of the Holy Land and also founded the Augustinian houses of Byland and Newburgh near to his castle in Thirsk. Given the number of northern saints commemorated in the calendar (Cuthbert and his translation, Wilfrid, John of Beverley and Oswald), it is likely that its first owner resided in a Northern Diocese while three commemorations of St Augustine point to a connection with the Augustinian Canons. The manuscript’s script and initials show close similarities to another English psalter now preserved in the Royal Library, Copenhagen (MS Thott 143), and it is probable that the two manuscripts were produced in the same scriptorium. The diocese of York is a reasonable place of origin, although Lincoln is another possibility. Neither this nor the Copenhagen Psalter has an entry in the Calendar for Thomas Becket, which suggests that they were completed some time before his canonization in 1173.