Greatlakereviewspring'11.Pdf (1.402Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Urban Dwellers and Neighborhood Nature: Exploring Urban Residents' Connection to Place, Community, and Environment

URBAN DWELLERS AND NEIGHBORHOOD NATURE: EXPLORING URBAN RESIDENTS' CONNECTION TO PLACE, COMMUNITY, AND ENVIRONMENT by SARAH P. CHURCH BMUS, The University of Idaho, 1996 MUP, The University of Utah, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Planning) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2013 © Sarah P. Church, 2013 Abstract Urban residents, in part due to issues of urban form and lifestyle choice, have become both physically and cognitively disconnected from the environment and natural processes – a disconnection that has contributed to decisions that have led to over consumption of natural resources and degradation of Earth. The form of the built environment has contributed to this separation, with city development embedded within infrastructures of concrete and pavement. Further, there is little attention paid to smaller scale integration of nature at the neighborhood level that might allow for frequent resident contact and activity. Today, whether in growth or decline, cities are faced with regulatory obligations and crumbling infrastructure. These issues are compounded by the pressing need to address sustainable development and resilience in the face of uncertainty around climate change and the need for reduced oil use. Incremental urban restructuring of neighborhoods through planning and designing to the specifics of local ecology (place-based design) has the potential to restore a balance between urban areas and natural systems. I therefore studied how urban residents perceive and interact with these systems in order to answer the question: How does active involvement in Portland’s Tabor to the River watershed health program foster place-based awareness and environmental learning? This dissertation is an exploratory qualitative case study undertaken in Portland, Oregon in which I conducted 42 semi-structured interviews of community members and 14 experts. -

W In, Lose, Or Draw Ji

Michigan Wins New Poll Over Notre Dame, 2 to 1 --- T.: ......;-i---1-1- Ballot Is 226 to 119 Yanks Sign Di Maggio Record Score Marks or Draw w in, Lose, At Believed Third Win By FRANCIS E. STANN In Special Vote of Figure Hogan's Dilemma in the Far West Nation's Writers Close to $70,000 At Los Angeles That curious hissing noise you may have been hearing in this fty Hm Aikoctotod Pr#kk ■y die Associated tr*u new year means, in all probability, that out on the West Coast those By Witt Grimsley NEW Jan. 6.—Joe Di LOS ANGELES, Jan. I.—Ben sponsors of the remarkable Rose Bowl pact between the Pacific Associated Press Sports Writer YORK, Mag- the gio of the Yankees announced today Hogan left town today, having ac- Conference and the Big Nine are rapidly approaching boiling NEW Jan. 6.—The burn- YORK, that he had signed a contract for complished the following feats In of the point. ing sport* question day— the coming season which made him the game of golf: The Coast Conference people who bought which was the greater college foot- "very happy,” and a consensus of Won the $10,000 Los Angeles Open have been ridiculed and ball of or this particular turkey power 1947, Michigan those who heard the great center- for the third time. Notre Dame—never to be settled on editorially tarred and feathered ever since they fielder express his pleasure placed Established a new the was answered today at record for the entered into an agreement which practically field, the amount of his stipend at close the ballot box—and it’s Michigan tournament at the Riviera Country handed over the Rose' Bowl to the Big Nine for to $70,000. -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

![COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5125/complete-music-list-by-artist-no-of-tunes-6773-465125.webp)

COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ]

[ COMPLETE MUSIC LIST by ARTIST ] [ No of Tunes = 6773 ] 001 PRODUCTIONS >> BIG BROTHER THEME 10CC >> ART FOR ART SAKE 10CC >> DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 10CC >> GOOD MORNING JUDGE 10CC >> I'M NOT IN LOVE {K} 10CC >> LIFE IS A MINESTRONE 10CC >> RUBBER BULLETS {K} 10CC >> THE DEAN AND I 10CC >> THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 >> DANCE WITH ME 1200 TECHNIQUES >> KARMA 1910 FRUITGUM CO >> SIMPLE SIMON SAYS {K} 1927 >> IF I COULD {K} 1927 >> TELL ME A STORY 1927 >> THAT'S WHEN I THINK OF YOU 24KGOLDN >> CITY OF ANGELS 28 DAYS >> SONG FOR JASMINE 28 DAYS >> SUCKER 2PAC >> THUGS MANSION 3 DOORS DOWN >> BE LIKE THAT 3 DOORS DOWN >> HERE WITHOUT YOU {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> KRYPTONITE {K} 3 DOORS DOWN >> LOSER 3 L W >> NO MORE ( BABY I'M A DO RIGHT ) 30 SECONDS TO MARS >> CLOSER TO THE EDGE 360 >> LIVE IT UP 360 >> PRICE OF FAME 360 >> RUN ALONE 360 FEAT GOSSLING >> BOYS LIKE YOU 3OH!3 >> DON'T TRUST ME 3OH!3 FEAT KATY PERRY >> STARSTRUKK 3OH!3 FEAT KESHA >> MY FIRST KISS 4 THE CAUSE >> AIN'T NO SUNSHINE 4 THE CAUSE >> STAND BY ME {K} 4PM >> SUKIYAKI 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> DON'T STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> GIRLS TALK BOYS {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> LIE TO ME {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> SHE'S KINDA HOT {K} 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> TEETH 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> WANT YOU BACK 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER >> YOUNGBLOOD {K} 50 CENT >> 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT >> AYO TECHNOLOGY 50 CENT >> CANDY SHOP 50 CENT >> IF I CAN'T 50 CENT >> IN DA CLUB 50 CENT >> P I M P 50 CENT >> PLACES TO GO 50 CENT >> WANKSTA 5000 VOLTS >> I'M ON FIRE 5TH DIMENSION -

First and Second Degree Black Belt Training Manual

First and Second Degree Black Belt Training Manual Developed by: Adam J. Boisvert, A-5-19 Chief Instructor & Shannon L. Boisvert, A-3-31 Assistant Chief Instructor Black Belt: Expert or Novice One of the greatest misconceptions within the martial arts is the notion that all black belt holders are experts. It is understandable that those unacquainted with the martial arts might make this equation. However, students should certainly recognize that this is not always the case. Too often, novice black belt holders advertise themselves as experts and eventually even convince themselves. The black belt holder has usually learned enough technique to defend themselves against single opponents of average ability. They can be compared to a fledgling that has acquired enough feathers to leave the nest and fend for themselves. The first degree is a starting point. The student has merely built a foundation. The job of building the house lies ahead. The novice black belt holder will now really begin to learn technique. Now that they have mastered the alphabet, they can now begin to read. Years of hard work and study await them before they can even begin to consider themselves an instructor or expert. A good student will, at this stage, suddenly realize how very little they know. The black belt holder also enters a new era of responsibility. Though a freshman, they have entered a strong honorable fraternity of the black belt holders of the entire world; and their actions inside and outside the training hall will be carefully scrutinized. Their conduct will reflect on all black belt holders and they must constantly strive to set an example for all grade holders. -

Indian Horse

Contents 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | 50 | 51 | 52 | 53 | 54 | 55 | 56 Acknowledgements | Copyright For my wife, Debra Powell, for allowing me to bask in her light and become more. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free. WENDELL BERRY, “The Peace of Wild Things” 1 My name is Saul Indian Horse. I am the son of Mary Mandamin and John Indian Horse. My grandfather was called Solomon so my name is the diminutive of his. My people are from the Fish Clan of the northern Ojibway, the Anishinabeg, we call ourselves. We made our home in the territories along the Winnipeg River, where the river opens wide before crossing into Manitoba after it leaves Lake of the Woods and the rugged spine of northern Ontario. They say that our cheekbones are cut from those granite ridges that rise above our homeland. They say that the deep brown of our eyes seeped out of the fecund earth that surrounds the lakes and marshes. The Old Ones say that our long straight hair comes from the waving grasses that thatch the edges of bays. -

New Bridge Groundbreaking Bridge to Be Replaced South Amboy

South Amboy-Sayreville Times September 26, 2020 1 South Amboy New Bridge Groundbreaking Earthquake Shakes Receives FEMA Grant (Photos by Tom Burkard) Area Mayor Fred Henry is pleased to By Tom Burkard announce that the City of South Amboy A 3.1 magnitude earthquake shook is the recipient of a grant from the 2020 parts of Central Jersey, and also was felt in Assistance to Firefighters Grant Program our local communities of South Amboy and Covid-19 Supplemental. Each year the Sayreville. On September 9th, the impact was Federal Government makes available funding felt in the area around 2 a.m., and lasted for to local firefighters to offset local costs for only around 13 seconds. The center of the various needs. This year FEMA earmarked earthquakes was pinpointed 1 ½ miles below this funding to offset purchase costs for ground near Freehold Township. In South Personal Protective Equipment [PPE] to limit Amboy, a person said it “Felt like the house exposure of First Responders to Covid-19. shook briefly,” and a Sayreville woman said Funding received from this grant “It sounded like a loud boom outside of our provided for the purchase of facepiece home.” Fortunately, no injuries or structural adapters that allow our Firefighters to utilize damage was reported, but police received their breathing masks to prevent exposure to numerous calls. airborne diseases. Mayor Henry said “we always pursue Poll Workers Needed grant opportunities when available, John Anagnostis Regional Vice Chair particularly when it allows us to enhance of the Middlesex County Republican the safety of our First Responders. -

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Marxman Mary Jane Girls Mary Mary Carolyne Mas

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red 12 Dec 98 Take Me There (Blackstreet & Mya featuring Mase & Blinky Blink) 7 9 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. 10 Jul 99 Get Ready 32 4 20 Nov 04 Welcome Back/Breathe Stretch Shake 29 2 MARXMAN Total Hits : 8 Total Weeks : 45 Anglo-Irish male rap/vocal/DJ group - Stephen Brown, Hollis Byrne, Oisin Lunny and DJ K One 06 Mar 93 All About Eve 28 4 MASH American male session vocal group - John Bahler, Tom Bahler, Ian Freebairn-Smith and Ron Hicklin 01 May 93 Ship Ahoy 64 1 10 May 80 Theme From M*A*S*H (Suicide Is Painless) 1 12 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 5 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 12 MARY JANE GIRLS American female vocal group, protégées of Rick James, made up of Cheryl Ann Bailey, Candice Ghant, MASH! Joanne McDuffie, Yvette Marine & Kimberley Wuletich although McDuffie was the only singer who Anglo-American male/female vocal group appeared on the records 21 May 94 U Don't Have To Say U Love Me 37 2 21 May 83 Candy Man 60 4 04 Feb 95 Let's Spend The Night Together 66 1 25 Jun 83 All Night Long 13 9 Total Hits : 2 Total Weeks : 3 08 Oct 83 Boys 74 1 18 Feb 95 All Night Long (Remix) 51 1 MASON Dutch male DJ/producer Iason Chronis, born 17/1/80 Total Hits : 4 Total Weeks : 15 27 Jan 07 Perfect (Exceeder) (Mason vs Princess Superstar) 3 16 MARY MARY Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 16 American female vocal duo - sisters Erica (born 29/4/72) & Trecina (born 1/5/74) Atkins-Campbell 10 Jun 00 Shackles (Praise You) -

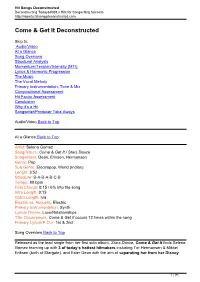

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential. -

WOLF 359 "BRAVE NEW WORLD" by Gabriel Urbina Story By: Sarah Shachat & Gabriel Urbina

WOLF 359 "BRAVE NEW WORLD" by Gabriel Urbina Story by: Sarah Shachat & Gabriel Urbina Writer's Note: This episode takes place starting on Day 1220 of the Hephaestus Mission. FADE IN: On HERA. Speaking directly to us. HERA So here's a story. Once upon a time, there lived a broken little girl. She was born with clouded eyes, and a weak heart, not destined to beat through an entire lifetime. But instead of being wretched or afraid, the little girl decided to be clever. She got very, very good at fixing things. First she fixed toys, and clocks, and old machines that no one thought would ever run again. Then, she fixed bigger things. She fixed the cold and drafty orphanage where she grew up; when she went to school, she fixed equations to make them more useful; everything around her, she made better... and sharper... and stronger. She had no friends, of course, except for the ones she made. The little girl had a talent for making dolls - beautiful, wonderful mechanical dolls - and she thought they were better friends than anyone in the world. They could be whatever she wanted them to be - and as real as she wanted them to be - and they never left her behind... and they never talked back... and they were never afraid of her. Except when she wanted them to be. But if there was one thing the girl never felt like she could fix, it was herself. Until... one day a strange thing happened. The broken girl met an old man - older than anyone she had ever met, but still tricky and clever, almost as clever as the girl.