Body Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward J. Dudley

Edward J. Dudley Bulletin of the CervantesCervantes Society of America The Cervantes Society of America President Frederick De Armas (2007-2010) Vice-President Howard Mancing (2007-2010) Secretary-Treasurer Theresa Sears (2007-2010) Executive Council Bruce Burningham (2007-2008) Charles Ganelin (Midwest) Steve Hutchinson (2007-2008) William Childers (Northeast) Rogelio Miñana (2007-2008) Adrienne Martin (Pacific Coast) Carolyn Nadeau (2007-2008) Ignacio López Alemany (Southeast) Barbara Simerka (2007-2008) Christopher Weimer (Southwest) Cervantes: Bulletin of the Cervantes Society of America Editor: Tom Lathrop (2008-2010) Managing Editor: Fred Jehle (2007-2010) Book Review Editor: William H. Clamurro (2007-2010) Associate Editors Antonio Bernat Adrienne Martin Jean Canavaggio Vincent Martin Jaime Fernández Francisco Rico Edward H. Friedman George Shipley Luis Gómez Canseco Eduardo Urbina James Iffland Alison P. Weber Francisco Márquez Villanueva Diana de Armas Wilson Cervantes is official organ of the Cervantes Society of America It publishes scholarly articles in English and Spanish on Cervantes’ life and works, reviews, and notes of interest to Cervantistas. Twice yearly. Subscription to Cervantes is a part of membership in the Cervantes Society of America, which also publishes a newsletter: $25.00 a year for individuals, $50.00 for institutions, $30.00 for couples, and $10.00 for students. Membership is open to all persons interested in Cervantes. For membership and subscription, send check in us dollars to Carolyn Nadeau, Buck 015; Illinois Wesleyan Univer- sity; Bloomington, Illinois 61701 ([email protected]), Or google Cervantes become a member + “I’m feeling lucky” for the payment page. The journal style sheet is at http://www.h-net.org/~cervantes/ bcsalist.htm. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Written by Nikyatu Jusu

NANNY Written by Nikyatu Jusu “For the mouths of her children quickly forgot the taste of her nipples, and years ago they had begun to look past her face into the nearest stretch of sky.” --Toni Morrison, Sula Cherry Rev. (7/18/20) 2. 1 INT. UPPER EAST SIDE APARTMENT - DAY 1 THE SOUND OF WATER RUNNING, unfettered, unencumbered--perhaps overflowing... We creep through a longish hallway littered with doorways and framed pictures. In these pictures are various poses of a PERFECT UPPER EAST SIDE FAMILY comprised of a WHITE COUPLE [30’s] and their angelic BABY BOY [4]. At the foot of one doorway, shards of light refract like luminescent knives off a pool of blood. We float past... A faintly discernible larger than life arachnid shadow ambles along hallway walls. Whispers. Barely discernible--then louder emanate from-- An AFRO-DOMINICAN WOMAN [45], at the end of the hallway. Her back is to us. She’s frantic. Desperate. She presses a phone to her ear--in her other hand: a top of the line, bloody, French Laguiole steak knife. She stumbles through tears. AFRO DOMINICAN WOMAN (spanish) I...don’t know. I don’t know what happened. I was tired. Confused. It wasn’t the boy. It was something else-- An INHUMAN GROAN echoes just behind her. She freezes, turning slowly and we see her face for the first time: palpable fear. Defense scratches etch her face. A SMALL SPIDER emerges from her ear, making its way across her cheek. She drops the bloody phone as she faces an ANIMALISTIC WAIL. -

Honeybees, Flowers And

A Prelude to Spring the AlTIerican Horticultural Society visifs Charleston April 9-12, 1978 From the moment you are registered at the historic • A visit to Middleton Place, America's oldest land Mills Hyatt House you will witness a rebirth of an scaped gardens, with its artistry of green sculptured tebellum elegance. Your headquarters hotel is the old terraces, butterfly lakes and reflecting pools and quaint est in Charleston; it is also the newest. It opened its wooden bridges. (Cocktails, dinner, musical enter doors in 1853, when Charleston was the " Queen City tainment and tour.) OF the South" . rich, sophisticated, urbane. The • Drayton Hall, the finest untouched example of Mills Hyatt House served as a center of refinement and Georgian architecture standing in North America, lo gracious living. Recently this landmark was recon cated on the Ashley River and surrounded by more structed and preserved as a focal point in Charleston's than 100 acres. (Lunch and tour sponsored by the Na historic district. You will find the Mills Hyatt House tional Trust for Historic Preservation.) one of the most unusual and handsome hotels in • Charles Towne Landing, 200-acre exhibition park America. graced with ancient live oaks flanked by azaleas You are invited to join us and experience the charm draped with grey lace Spanish moss. Wander through of Charleston, a city that combines a unique gardening the English park gardens with acres and acres filled heritage, antebellum architecture, and modern with hundreds of trees and flowers arranged to facilities. provide interest and beauty. (Lunch, animal forest Charleston is in many ways unique, for she was the tour, guided tram rides.) first American city to protect and preserve the fine old buildings and gardens which have witnessed so much • Magnolia Plantation and Gardens. -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

A Qualitative Study On

2018 2018 A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON PREVALENCE SURVEY OF COUNTERMEASURES DRUG ABUSE OF SURVEY PREVALENCE ON STUDY A QUALITATIVE PREVALENCE SURVEY OF DRUG ABUSE COUNTERMEASURES DRUG ABUSE COUNTERMEASURES urrently, the country has stated that Indonesia is in drug Cemergency situation as drug abuse has touched all layers of the society and all areas in Indonesia. In 2018, National Narcotics Board (BNN) in cooperation with Society and Cultural Research Center LIPI conducted the survey on prevalence rate of drug abuse. The objective of this qualitative study is to find out drug trafficking, factor in drug abuse, impact of drug abuse, and Prevention and Eradication Drug Abuse and Illicit Trafficking (P4GN) implementation in each province. This qualitative study is aimed to support quantitative data on prevalence rate of drug abuse in Indonesia in 2019. Research, Data, and Information Center National Narcotics Board (PUSLITDATIN BNN) Image by: mushroomneworleans.com 2018 Jl. MT Haryono No. 11 Cawang. East Jakarta Website : www.bnn.go.id Kratom Email : [email protected] (Mitragyna Speciosa) Call Center : 184 SMS Center : 0812-221-675-675 A QUALITATIVE STUDY ON PREVALENCE SURVEY OF DRUG ABUSE COUNTERMEASURES 2018 RESEARCH, DATA, AND INFORMATION CENTER NATIONAL NARCOTICS BOARD THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA 2019 ISBN : 978-623-93034-0-2 A Qualitative Study on Prevalence Survey of Drug Abuse Countermeasures 2018 Copyright @2019 Editorial Board : Supervisor : Drs. Agus Irianto, S.H., M.Si, M.H. Advisor : Dr. Sri Sunarti Purwaningsih, M.A Drs. Masyhuri Imron, M.A Chief Editor : Dra. Endang Mulyani, M.Si Secretary : Siti Nurlela Marliani, SP., S.H., M.Si Team Members : Dwi Sulistyorini, S.Si., M.Si Sri Lestari, S.Kom., M.Si Novita Sari, S.Sos., M.H Erma Antasari, S.Si Sri Haryanti, S.Sos., M.Si Quazar Noor Azhim, A.Md Rizky Purnamasari, S.Psi Armita Eki Indahsari, S.Si Radityo Kunto Harimurti, S. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

The World Without a Self

The World Without a Self Virginia Woolf and the Novel by fames Naremore New Haven and London, Yale University Press, r973 Copyright © z973 by Ya/,e University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Library of Congress catalog card number: 72-9z3z5 International standard book number: o-300-oz594-z Designed by Sally Sullivan and set in Unotype Granjon type, Printed in the United States of America by The Colonial Press Inc., Clinton, Massachusetts. Published in Great Britain, Europe, and Africa by Yale University Press, Ltd., London. Distributed in Canada by McGill-Queen's University Press, Montreal; in Latin America by Kaiman & Polan, Inc., New York City; in Austra/,asia and Southeast Asia by John Wiley & Sons Austra/,asia Pty. Ltd., Sydney; in India by UBS Publishers' Distributors Pvt., Ltd., Delhi; in .fapan by .fohn Weatherhill, Inc., Tokyo. For Rita and Jay What art was there, known to love or cunning, by which one pressed into those secret chambers? What device for becoming, like waters poured into one jar, one with the object one adored? Lily Briscoe in To the Lighthouse "How describe the world seen without a self?" Bernard in The Waves Contents Acknowledgments xi 1 Introduction 1 2 A Passage from The Voyage Out 5 3 The Artist as Lover: The Voyage Out Continued 30 4 Virginia W 001£ and the Stream of Consciousness 60 5 Mrs. Dal.loway 77 6 To the Lighthouse rr2 7 The Waves 151 8 Orlando and the "New Biography" 190 9 The "Orts and Fr-agments" in Between the Acts 219 ro Conclusion 240 ·Bibliography 249 Index 255 Acknowledgments Portions of this book have appeared in Novel: A Forum on Fiction, and in The Ball State University Forum. -

Who's Holiday!

Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 1 of 48 EXHIBIT 1 THE PLAY Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 2 of 48 WHO’S HOLIDAY! A Christmas Comedy in Couplets by MATTHEW LOMBARDO Represented By: MARK D. SENDROFF, ESQ. Sendroff and Baruch, LLP 1500 Broadway Suite 2201 New York, New York 10036 FIRST REHEARSAL DRAFT (212) 840-6400 September 26, 2016 [email protected] © All Rights Reserved Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 3 of 48 2 CAST OF CHARACTERS CINDY LOU WHO, 45, . JENNIFER SIMARD Unlike the bright-eyed character of her youth, she is no longer an innocent. Having been dealt a tough hand in the game of life, she desperately attempts to remain cheery in all situations. Despite her style-challenged attire and now poorly permed bleached blond hair, there still is a glimmer of hope in her beaten down spirit. SETTING A silver bullet trailer in the snowy hills of Mount Crumpit TIME Christmas Eve WHO’S HOLIDAY is performed without an intermission. Case 1:16-cv-09974-AKH Document 1-1 Filed 12/27/16 Page 4 of 48 3 WHO’S HOLIDAY! The curtain rises on the interior of an older, modest Airstream silver bullet trailer. The furniture is well worn, the carpet has cigarette burns, and the overall taste is reminiscent of 1970’s suburbia. The home is decorated for the holiday, with colored lights strung around the windows, holly and lit plastic snowmen strategically placed, and a not so tasteful Christmas tree in the corner of the main room. -

(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena

(You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) 3 AM ± Matchbox Twenty. 99 Red Ballons ± Nena. Against All Odds ± Phil Collins. Alive and kicking- Simple minds. Almost ± Bowling for soup. Alright ± Supergrass. Always ± Bon Jovi. Ampersand ± Amanda palmer. Angel ± Aerosmith Angel ± Shaggy Asleep ± The Smiths. Bell of Belfast City ± Kristy MacColl. Bitch ± Meredith Brooks. Blue Suede Shoes ± Elvis Presely. Bohemian Rhapsody ± Queen. Born In The USA ± Bruce Springstein. Born to Run ± Bruce Springsteen. Boys Will Be Boys ± The Ordinary Boys. Breath Me ± Sia Brown Eyed Girl ± Van Morrison. Brown Eyes ± Lady Gaga. Chasing Cars ± snow patrol. Chasing pavements ± Adele. Choices ± The Hoosiers. Come on Eileen ± Dexy¶s midnight runners. Crazy ± Aerosmith Crazy ± Gnarles Barkley. Creep ± Radiohead. Cupid ± Sam Cooke. Don¶t Stand So Close to Me ± The Police. Don¶t Speak ± No Doubt. Dr Jones ± Aqua. Dragula ± Rob Zombie. Dreaming of You ± The Coral. Dreams ± The Cranberries. Ever Fallen In Love? ± Buzzcocks Everybody Hurts ± R.E.M. Everybody¶s Fool ± Evanescence. Everywhere I go ± Hollywood undead. Evolution ± Korn. FACK ± Eminem. Faith ± George Micheal. Feathers ± Coheed And Cambria. Firefly ± Breaking Benjamin. Fix Up, Look Sharp ± Dizzie Rascal. Flux ± Bloc Party. Fuck Forever ± Babyshambles. Get on Up ± James Brown. Girl Anachronism ± The Dresden Dolls. Girl You¶ll Be a Woman Soon ± Urge Overkill Go Your Own Way ± Fleetwood Mac. Golden Skans ± Klaxons. Grounds For Divorce ± Elbow. Happy ending ± MIKA. Heartbeats ± Jose Gonzalez. Heartbreak Hotel ± Elvis Presely. Hollywood ± Marina and the diamonds. I don¶t love you ± My Chemical Romance. I Fought The Law ± The Clash. I Got Love ± The King Blues. I miss you ± Blink 182. -

DJ Playlist.Djp

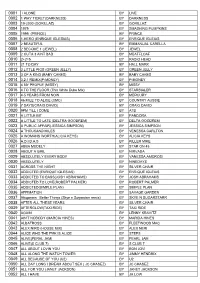

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE