SONGS from the OTHER SIDE of the WALL Dan Holloway

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

'Boxing Clever

NOVEMBER 05 2018 sandboxMUSIC MARKETING FOR THE DIGITAL ERA ISSUE 215 ’BOXING CLEVER SANDBOX SUMMIT SPECIAL ISSUE Event photography: Vitalij Sidorovic Music Ally would like to thank all of the Sandbox Summit sponsors in association with Official lanyard sponsor Support sponsor Networking/drinks provided by #MarketMusicBetter ast Wednesday (31st October), Music Ally held our latest Sandbox Summit conference in London. While we were Ltweeting from the event, you may have wondered why we hadn’t published any reports from the sessions on our site and ’BOXING CLEVER in our bulletin. Why not? Because we were trying something different: Music Ally’s Sandbox Summit conference in London, IN preparing our writeups for this special-edition sandbox report. From the YouTube Music keynote to panels about manager/ ASSOCIATION WITH LINKFIRE, explored music marketing label relations, new technology and in-house ad-buying, taking in Fortnite and esports, Ed Sheeran, Snapchat campaigns and topics, as well as some related areas, with a lineup marketing to older fans along the way, we’ve broken down the key views, stats and debates from our one-day event. We hope drawn from the sharp end of these trends. you enjoy the results. :) 6 | sandbox | ISSUE 215 | 05.11.2018 TALES OF THE ’TUBE Community tabs, premieres and curation channels cited as key tools for artists on YouTube in 2018 ensions between YouTube and the music industry remain at raised Tlevels following the recent European Parliament vote to approve Article 13 of the proposed new Copyright Directive, with YouTube’s CEO Susan Wojcicki and (the day after Sandbox Summit) music chief Lyor Cohen both publicly criticising the legislation. -

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love

Artist Song Title N/A Swedish National Anthem 411 Dumb 702 I Still Love You 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 911 More Than A Woman 1927 Compulsory Hero 1927 If I Could 1927 That's When I Think Of You Ariana Grande Dangerous Woman "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Eat It "Weird Al" Yankovic White & Nerdy *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye *NSYNC (God Must Have Spent) A Little More Time On You *NSYNC I'll Never Stop *NSYNC It's Gonna Be Me *NSYNC No Strings Attached *NSYNC Pop *NSYNC Tearin' Up My Heart *NSYNC That's When I'll Stop Loving You *NSYNC This I Promise You *NSYNC You Drive Me Crazy *NSYNC I Want You Back *NSYNC Feat. Nelly Girlfriend £1 Fish Man One Pound Fish 101 Dalmations Cruella DeVil 10cc Donna 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Mandy 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Wall Street Shuffle 10cc Don't Turn Me Away 10cc Feel The Love 10cc Food For Thought 10cc Good Morning Judge 10cc Life Is A Minestrone 10cc One Two Five 10cc People In Love 10cc Silly Love 10cc Woman In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About Belief) 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 2nd Baptist Church (Lauren James Camey) Rise Up 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

The American Ceramic Society 25Th International Congress On

The American Ceramic Society 25th International Congress on Glass (ICG 2019) ABSTRACT BOOK June 9–14, 2019 Boston, Massachusetts USA Introduction This volume contains abstracts for over 900 presentations during the 2019 Conference on International Commission on Glass Meeting (ICG 2019) in Boston, Massachusetts. The abstracts are reproduced as submitted by authors, a format that provides for longer, more detailed descriptions of papers. The American Ceramic Society accepts no responsibility for the content or quality of the abstract content. Abstracts are arranged by day, then by symposium and session title. An Author Index appears at the back of this book. The Meeting Guide contains locations of sessions with times, titles and authors of papers, but not presentation abstracts. How to Use the Abstract Book Refer to the Table of Contents to determine page numbers on which specific session abstracts begin. At the beginning of each session are headings that list session title, location and session chair. Starting times for presentations and paper numbers precede each paper title. The Author Index lists each author and the page number on which their abstract can be found. Copyright © 2019 The American Ceramic Society (www.ceramics.org). All rights reserved. MEETING REGULATIONS The American Ceramic Society is a nonprofit scientific organization that facilitates whether in print, electronic or other media, including The American Ceramic Society’s the exchange of knowledge meetings and publication of papers for future reference. website. By participating in the conference, you grant The American Ceramic Society The Society owns and retains full right to control its publications and its meetings. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Goldfrapp (Medley) Can't Help Falling Elvis Presley John Legend In Love Nelly (Medley) It's Now Or Never Elvis Presley Pharrell Ft Kanye West (Medley) One Night Elvis Presley Skye Sweetnam (Medley) Rock & Roll Mike Denver Skye Sweetnam Christmas Tinchy Stryder Ft N Dubz (Medley) Such A Night Elvis Presley #1 Crush Garbage (Medley) Surrender Elvis Presley #1 Enemy Chipmunks Ft Daisy Dares (Medley) Suspicion Elvis Presley You (Medley) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley Daisy Dares You & (Olivia) Lost And Turned Whispers Chipmunk Out #1 Spot (TH) Ludacris (You Gotta) Fight For Your Richard Cheese #9 Dream John Lennon Right (To Party) & All That Jazz Catherine Zeta Jones +1 (Workout Mix) Martin Solveig & Sam White & Get Away Esquires 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & I Ciara 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z Ft Beyonce & I Am Telling You Im Not Jennifer Hudson Going 1 3 Dog Night & I Love Her Beatles Backstreet Boys & I Love You So Elvis Presley Chorus Line Hirley Bassey Creed Perry Como Faith Hill & If I Had Teddy Pendergrass HearSay & It Stoned Me Van Morrison Mary J Blige Ft U2 & Our Feelings Babyface Metallica & She Said Lucas Prata Tammy Wynette Ft George Jones & She Was Talking Heads Tyrese & So It Goes Billy Joel U2 & Still Reba McEntire U2 Ft Mary J Blige & The Angels Sing Barry Manilow 1 & 1 Robert Miles & The Beat Goes On Whispers 1 000 Times A Day Patty Loveless & The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen 1 2 I Love You Clay Walker & The Crowd Goes Wild Mark Wills 1 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott & The Grass Wont Pay -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

DJ Playlist.Djp

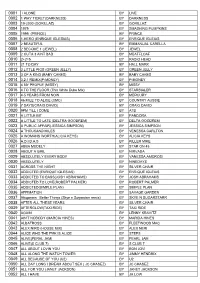

0001 I ALONE BY LIVE 0002 1 WAY TICKET(DARKNESS) BY DARKNESS 0003 19-2000 (GORILLAZ) BY GORILLAZ 0004 1979 BY SMASHING PUMPKINS 0005 1999 (PRINCE) BY PRINCE 0006 1-HERO (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0007 2 BEAUTIFUL BY EMMANUAL CARELLA 0008 2 BECOME 1 (JEWEL) BY JEWEL 0009 2 OUTA 3 AINT BAD BY MEATFLOAF 0010 2+2=5 BY RADIO HEAD 0011 21 TO DAY BY HALL MARK 0012 3 LITTLE PIGS (GREEN JELLY) BY GREEN JELLY 0013 3 OF A KIND (BABY CAKES) BY BABY CAKES 0014 3,2,1 REMIX(P-MONEY) BY P-MONEY 0015 4 MY PEOPLE (MISSY) BY MISSY 0016 4 TO THE FLOOR (Thin White Duke Mix) BY STARSIALER 0017 4-5 YEARS FROM NOW BY MERCURY 0018 46 MILE TO ALICE (CMC) BY COUNTRY AUSSIE 0019 7 DAYS(CRAIG DAVID) BY CRAIG DAVID 0020 9PM TILL I COME BY ATB 0021 A LITTLE BIT BY PANDORA 0022 A LITTLE TO LATE (DELTRA GOODREM) BY DELTA GOODREM 0023 A PUBLIC AFFAIR(JESSICA SIMPSON) BY JESSICA SIMPSON 0024 A THOUSAND MILES BY VENESSA CARLTON 0025 A WOMANS WORTH(ALICIA KEYS) BY ALICIA KEYS 0026 A.D.I.D.A.S BY KILLER MIKE 0027 ABBA MEDELY BY STAR ON 45 0028 ABOUT A GIRL BY NIRVADA 0029 ABSOLUTELY EVERY BODY BY VANESSA AMOROSI 0030 ABSOLUTELY BY NINEDAYS 0031 ACROSS THE NIGHT BY SILVER CHAIR 0032 ADDICTED (ENRIQUE IGLESIAS) BY ENRIQUE IGLEIAS 0033 ADDICTED TO BASS(JOSH ABRAHAMS) BY JOSH ABRAHAMS 0034 ADDICTED TO LOVE(ROBERT PALMER) BY ROBERT PALMER 0035 ADDICTED(SIMPLE PLAN) BY SIMPLE PLAN 0036 AFFIMATION BY SAVAGE GARDEN 0037 Afropeans Better Things (Skye n Sugarstarr remix) BY SKYE N SUGARSTARR 0038 AFTER ALL THESE YEARS BY SILVER CHAIR 0039 AFTERGLOW(TAXI RIDE) BY TAXI RIDE -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

Black Rage VI Denison University

Denison University Denison Digital Commons Writing Our Story Black Studies 2005 Black Rage VI Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory Recommended Citation Denison University, "Black Rage VI" (2005). Writing Our Story. 98. http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/writingourstory/98 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Black Studies at Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Writing Our Story by an authorized administrator of Denison Digital Commons. ~It ...... 1 ei ll e:· CU· st. C jll eli [I C,I ei l .J C.:a, •.. a4 II a.il .. a,•• as II at iI Uj 'I Uj iI ax cil ui 11 a: c''. iI •a; a,iI'. u,· u,•• a: • at , 3,,' .it Statement of Purpose: To allow for a creative outlet for students of the Black Student Union of Denison University. Dedicated to Introduction The Black Student Union The need for this publication came about when the expres· Spring 2005 sions of a number of Black students were denied from other campus publications without any valid justification. As his tory has proven, when faced With limitations, we as Black people then create a means for overcoming that limitation a means that is significant to our own interests and beliefs. Therefore, we came together as a Black community in search of resolution, and decided on Black Rage as the instrument by which we would let our creative voices sing. This unprecedented publication serves as a refuge for the Black students at Denison University, by offering an avenue for our poetry, prose, short stories as well as other unique writings to be read, respected, and held in utmost regard. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C.