Strange Interlude Background Pack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Session 3 - the Difference Jesus Makes

Session 3 - The difference Jesus makes Session 3 - The difference Jesus makes Aims and outcomes You will need: Take time to think about and pray over each member l Fabric and other props to create the Easter story of the group, holding them before God and praying that scene their needs are met. Think about how well the group is l Name and locations for the Good Friday story gelling, and whether people are sticking to the ground scene (see pp. 17-18) rules (Compass, p. 5). Are any gentle reminders needed? l Cross (to include in the Good Friday story scene) Is there someone needing extra attention? Perhaps a l Candle (and matches) mentor to talk to? l Three or four copies of newspapers from this week Remind people briefly of the last session, when they l Chalice and paten (plate), bread and wine looked at the life of Jesus. Invite them to think about l Words describing difference Jesus makes on the their reflections at the end of the last session on what Cross (see pp. 19-21). it means to be transformed (Compass, p. 27). What are l Scissors to cut the words and names out (If you their questions at this point? have time they could be backed and made to stand up. But laying them on the scene works just This session will help participants reflect on different as well.) ways we try to understand the meaning of Jesus’ death. l Pens We can only get so far in looking for rational reasons l Bowl for the meaning of Jesus’ death. -

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996

Stage by Stage South Bank: 1988 – 1996 Stage by Stage The Development of the National Theatre from 1848 Designed by Michael Mayhew Compiled by Lyn Haill & Stephen Wood With thanks to Richard Mangan and The Mander & Mitchenson Theatre Collection, Monica Sollash and The Theatre Museum The majority of the photographs in the exhibition were commissioned by the National Theatre and are part of its archive The exhibition was funded by The Royal National Theatre Foundation Richard Eyre. Photograph by John Haynes. 1988 To mark the company’s 25th birthday in Peter Hall’s last year as Director of the National October, The Queen approves the title ‘Royal’ Theatre. He stages three late Shakespeare for the National Theatre, and attends an plays (The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and anniversary gala in the Olivier. Cymbeline) in the Cottesloe then in the Olivier, and leaves to start his own company in the The funds raised are to set up a National West End. Theatre Endowment Fund. Lord Rayne retires as Chairman of the Board and is succeeded ‘This building in solid concrete will be here by the Lady Soames, daughter of Winston for ever and ever, whatever successive Churchill. governments can do to muck it up. The place exists as a necessary part of the cultural scene Prince Charles, in a TV documentary on of this country.’ Peter Hall architecture, describes the National as ‘a way of building a nuclear power station in the September: Richard Eyre takes over as Director middle of London without anyone objecting’. of the National. 1989 Alan Bennett’s Single Spies, consisting of two A series of co-productions with regional short plays, contains the first representation on companies begins with Tony Harrison’s version the British stage of a living monarch, in a scene of Molière’s The Misanthrope, presented with in which Sir Anthony Blunt has a discussion Bristol Old Vic and directed by its artistic with ‘HMQ’. -

Uhm Phd 9205877 R.Pdf

· INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewri~er face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikeiy event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact liMI directly to order. U-M-I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, M148106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9205811 Political economy of passion: Tango, exoticism, and decolonization Savigliano, Marta Elena, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1991 Copyright @1991 by Savigliano, Marta Elena. -

Rock Bottom Junior Script by Craig Hawes

Rock Bottom Junior Script by Craig Hawes Speaking Roles 41 Minimum Cast Size 25 Duration (minutes) 80 2/270618/28 ISBN: 978 1 84237 158 9 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B78 2DP 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com Licences are always required when published musicals are performed. Licences for musicals are only available from the publishers of those musicals. There is no other source. All our Performing, Copying & Video Licences are valid for one year from the date of issue. If you are recycling a previously performed musical, NEW LICENCES MUST BE PURCHASED to comply with Copyright law required by mandatory contractual obligations to the composer. Prices of Licences and Order Form can be found on our website: www.musiclinedirect.com Rock Bottom – Script 1 CONTENTS Cast List .............................................................................................................................. 5 Speaking Roles By Number Of Lines................................................................................ 6 Suggested Cast List For 28 (And 25) Actors .................................................................... 8 Characters In Each Scene ................................................................................................ 10 List Of Properties ............................................................................................................. 11 Production Notes ............................................................................................................. -

Enjoy the Show Cinemas in 65 Countries Showed a National

Did you know? A production from 2,500 cinemas in 65 countries showed a National Theatre Live broadcast or screening in 2017 by William Shakespeare Cast, in order of speaking Musicians Caesar Tunji Kasim Magnus Mehta (Music Director / Agrippa Katy Stephens Percussion), Joley Cragg (Percussion), Enjoy the show Cleopatra Sophie Okonedo Kwêsi Edman (Cello), Sarah Manship Antony Ralph Fiennes (Woodwind), We hope you enjoy your National Theatre Please do let us know what you think Eros Fisayo Akinade Arngeir Hauksson (Guitar / Oud) Live screening. We make every attempt to through our channels listed below or Charmian Gloria Obianyo replicate the theatre experience as closely approach the cinema manager to share Iras Georgia Landers Production Team as possible for your enjoyment. your thoughts. Soothsayer Hiba Elchikhe Enobarbus Tim McMullan Director Simon Godwin Proculeius Ben Wiggins Set Designer Hildegard Bechtler Sicyon Official Shazia Nicholls Costume Designer Evie Gurney Tim Lutkin Connect with us Lepidus Nicholas Le Prevost Lighting Designer Thidias Sam Woolf Music Michael Bruce Pompey Sargon Yelda Movement Directors Jonathan Explore Never miss out Menas Gerald Gyimah Goddard Go behind the scenes of Antony & Cleopatra Get the latest news from Varrius Waleed Hammad Shelley Maxwell and learn more about how our broadcasts National Theatre Live straight Euphronius Nick Sampson Sound Designer Christopher Shutt happen on our website. to your inbox. Octavia Hannah Morrish Video Designer Luke Halls Canidius Alan Turkington Fight Director Kev McCurdy ntlive.com ntlive.com/signup Scarus Alexander Cobb Ventidius Henry Everett Broadcast Team Supernumeraries Samuel Arnold Catherine Deevy Director for Screen Tony Grech-Smith Join in Feedback Technical Producer Christopher C Bretnall Use #AntonyandCleopatra and be Share your thoughts by taking our Script Supervisor Amanda Church a part of the conversation online. -

Qjlir Fa Fentpalnrf

QJlir f a fentpalnrf Volume 16. Issue ^29. DURHAM, N. H., JUNE 3, 1926. Price, 10 Cents HARRY W. STEERE, JR. BOOK AND SCROLL PRES. HETZEL ON PRESIDENT OF CLASS EARLY TRYOUTS HOST TO VISITORS PLANS FOR ANNUAL COMMENCEMENT The final meeting of the year of Leads Graduates For Next Two Years FOR DEBATERS OF UNIVERSITY STAND COMPLETED TOUR OF EUROPE Book and Scroll was held in the par —Miss Marian Arthur Is Vice- lor of Smith H all last Monday night President— Class Day Speak Tau Kappa Alpha Latest at eight o’clock. Representatives of Group to Hear Lectures ers Chosen Commencement Speech by Dr. William F. Anderson By Well-Known Statesman Honorary Campus Society T h e N e w H a m p s h ir e , T h e Golden Bishop of the Methodist-Episcopal Church, Boston B u ll and Spires were guests of the Harry W. Steere, Jr., Amesbury, organization. WILL LEAVE JUNE 23 N. E. LEAGUE FORMED COMMENCEMENT BALL FRIDAY BEGINS PROGRAM Mass., was elected president of the The meeting was opened with in graduating class of the university at troductory remarks from President Party Will Consist of Educators, Ed Two Subjects for Debates— Probably a meeting of the seniors held in Neville, who stressed the necessity The Rev. Vaughan Dabney, Pastor of Second Church, Dorchester, Mass. to itors, and Other Men of Public Life Men’s and Two Women’s Inter Thompson Hall last Monday evening. of making plans for the coming year. Deliver Baccalaureate Sermon Sunday Morning in Men’s Gymnas — To Study Economic and Polit collegiate Contests— Tryouts Miss Marian Arthur, Manchester, The organization has some very in ium— Alumni Day Scheduled for Saturday— Week Ends ical Situation of Europe in September was elected vice-president; Elsworth teresting plans under way which will With Commencement Exercises Monday, June 14 D. -

Read the 2015/2016 Financial Statement

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 National Theatre Page 1 of 87 PUBLIC BENEFIT STATEMENT In developing the objectives for the year, and in planning activities, the Trustees have considered the Charity Commission’s guidance on public benefit and fee charging. The repertoire is planned so that across a full year it will cover the widest range of world class theatre that entertains, inspires and challenges the broadest possible audience. Particular regard is given to ticket-pricing, affordability, access and audience development, both through the Travelex season and more generally in the provision of lower price tickets for all performances. Geographical reach is achieved through touring and NT Live broadcasts to cinemas in the UK and overseas. The NT’s Learning programme seeks to introduce children and young people to theatre and offers participation opportunities both on-site and across the country. Through a programme of talks, exhibitions, publishing and digital content the NT inspires and challenges audiences of all ages. The Annual Report is available to download at www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/annualreport If you would like to receive it in large print, or you are visually impaired and would like a member of staff to talk through the publication with you, please contact the Board Secretary at the National Theatre. Registered Office & Principal Place of Business: The Royal National Theatre, Upper Ground, London. SE1 9PX +44 (0)20 7452 3333 Company registration number 749504. Registered charity number 224223. Registered in England. Page 2 of 87 CONTENTS Public Benefit Statement 2 Current Board Members 4 Structure, Governance and Management 5 Strategic Report 8 Trustees and Directors Report 36 Independent Auditors’ Report 45 Financial Statements 48 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Reference and Administrative Details of the Charity, Trustees and Advisors 86 In this document The Royal National Theatre is referred to as “the NT”, “the National”, and “the National Theatre”. -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

Llprefeired Stocw 1

28 THE ST. PAUL GLOBE, SUNDAY, MAY 13, 1900. "KIDSAPPED IX XEW YORK." MISS ! FAY'S SUCCESS successful and thoroughly meritorious American plays, and will be seen at the I Melodrama the Bill at tlte Grand Lends to a Return Engagement the Grand in the very near future, with the Thin Work. author, Russ Whytal, in the principal Coming: Week. part. The attraction at the Grand this week, i METROPOLITAN j^Lg^ The management of the Metropolitan The story of the play is domestic, with commencing tonight, will be Howard theater a story background of the Civil Hall's "Kidnapped In New York," have been fortunate in securing war, but with Fay it is not a melodrama, and the comedy And Barney Gilmore, formerly of and Anna Eva for a return, commenc- is Tonight-Tomorrow Night TUESDAY Gilmore ing Tuesday so important that it is in of Leonard, as the star, and a strong sup- evening, for the balance of one those Two Performances Only. the week, and special Miss characters that Mr. Whytal appears. Tha MIGHT porting company. by request emotional ..... "wSSST work is in hands Jsh.n Brandon, the treasurer of the Fay will give two matinees this week, th>3 of such ; fl"v w-v « Matinees Wednesday and Saturday on Wednesday well-known people as Mable Knowles, j - Manhattan club, is falsely accused of and Saturday, for ladies Angeline robbing the club, and goes only. Crowded houses have greeted Miss Miss S. Pullia, Mr. C. H. Gel- ! the safe of dart, Dingeon, Melville, Ryley's 1 Jos. -

August and September 2019

August & September 2019 BL4D Newsletter - Theatres and Museums 4th Kew Gardens - Free Guided Walking Royal Botanic Gardens Kew Tour with Sign Language 47 Kew Green Kew August Sunday 4th August 2019, 11.30am Richmond TW9 3AB st Deaf Friendly: Interactive Stockwood Discovery Centre 1 Aug – Science Exhibition London Road, Luton th 8 Sept 1st August – 8th September LU1 4LX 6th Captions: Jesus Christ Superstar Silk Street London, EC2Y 8DS Tuesday 6th Aug, 7.45pm Tel: 0207 638 8891 August [email protected] th Captions: the end of history Sloane Square London, SW1W 8AS 7 (live speech-to-text post-show talk) Box Office: 020 7565 5000 August Wednesday 7th August 7.30pm [email protected] 8th Captions: Present Laughter The Old Vic Thursday 8th Aug, 7.30pm The Cut, Waterloo August SE1 8NB 8th BSL interpreted post-show talk: Matthew Sadler’s Wells, Rosebery Bourne's Romeo and Juliet — New Adventures August Avenue, Thursday 8th August - 7:30pm London, EC1R 4TN th 8 Captions: Tree Young Vic, 66 The Cut, Waterloo August Thursday 8th Aug 7.30pm London, SE1 8LZ, Tel: 02079222922 9th BSL Tour: Cindy Sherman National Portrait Gallery, August Friday 9th August 2019, 19:30 St Martin’s Place, London WC2H OHE, The Roundhouse 10th Captions: Barber Shop Chronicles Saturday 10th August, 3pm 100a Chalk Farm Road August London, NW1 8EH th Captions: Pericles 21 New Globe Walk, 15 Thursday 15th August 7.30pm Bankside August London, SE1 9DT Royal Festival Hall, Belvedere 16th BSL: Duckie Summertime Special Road, London, SE1 8XX, August Friday 16th -

Types & Forms of Theatres

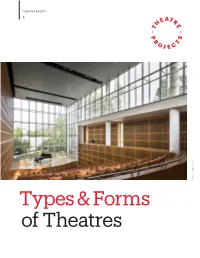

THEATRE PROJECTS 1 Credit: Scott Frances Scott Credit: Types & Forms of Theatres THEATRE PROJECTS 2 Contents Types and forms of theatres 3 Spaces for drama 4 Small drama theatres 4 Arena 4 Thrust 5 Endstage 5 Flexible theatres 6 Environmental theatre 6 Promenade theatre 6 Black box theatre 7 Studio theatre 7 Courtyard theatre 8 Large drama theatres 9 Proscenium theatre 9 Thrust and open stage 10 Spaces for acoustic music (unamplified) 11 Recital hall 11 Concert halls 12 Shoebox concert hall 12 Vineyard concert hall, surround hall 13 Spaces for opera and dance 14 Opera house 14 Dance theatre 15 Spaces for multiple uses 16 Multipurpose theatre 16 Multiform theatre 17 Spaces for entertainment 18 Multi-use commercial theatre 18 Showroom 19 Spaces for media interaction 20 Spaces for meeting and worship 21 Conference center 21 House of worship 21 Spaces for teaching 22 Single-purpose spaces 22 Instructional spaces 22 Stage technology 22 THEATRE PROJECTS 3 Credit: Anton Grassl on behalf of Wilson Architects At the very core of human nature is an instinct to musicals, ballet, modern dance, spoken word, circus, gather together with one another and share our or any activity where an artist communicates with an experiences and perspectives—to tell and hear stories. audience. How could any one kind of building work for And ever since the first humans huddled around a all these different types of performance? fire to share these stories, there has been theatre. As people evolved, so did the stories they told and There is no ideal theatre size. The scale of a theatre the settings where they told them. -

Place, Tourism and Belonging

18 The National Theatre, London, as a theatrical/architectural object of fan imagination Matt Hills Introduction Stijn Reijnders has argued that “memory seems to play an important part in the way in which places of the imagination are experienced. In other words, one can identify a certain reciprocity between memory and imagination” ( 2011 : 113). This chapter builds on such a recognition by focusing on the “mnemonic imagination” ( Keightley & Pickering, 2012) within place-making affects. At the same time, I am responding to the question of whether it is “possible to be a fan of a destination?” ( Linden & Linden, 2017 : 110). As Rebecca Williams (2018: 104) has recently argued, we need a greater under- standing of what places can do to visitors who may not bring particular media or fan-specific imaginative expectations with them and yet may respond strongly to a particular place. What confluence of affective, emo- tional and experiential elements may cause them to become fans of that site . .? By focusing on the Royal National Theatre on the South Bank of London – usually referred to as the “National Theatre” or the “NT” – I am deliber- ately taking a case study which multiplies some of these questions, since the NT has acted as the site for both theatre fandom (Hills, 2017 ) and what has been termed “architectural enthusiasm” (Craggs et al., 2013 , 2016 ). Indeed, the National Theatre has been marked by a related doubling through- out its history (having opened in 1976 after a much-delayed construction process). For, as Daniel Rosenthal (2013 : 845) observes in The National Theatre Story , it represents “what [playwright] Tom Stoppard termed co- existent institutions: ‘One was the ideal of a national theatre; the other was the building’”.