Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Requisites of Leadership in the Modern House of Commons 1

Number 4 November 2001 CANADIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP HE EQUISITES OF EADERSHIP THE REQUISITES OF LEADERSHIP IN THE MODERN HOUSE OF COMMONS Paper by: Cristine de Clercy Department of Political Studies University of Saskatchewan Canadian Members of the Study of Parliament Executive Committee Group 2000-2001 The Canadian Study of President Parliament Group (CSPG) was created Leo Doyle with the object of bringing together all those with an interest in parliamentary Vice-President institutions and the legislative F. Leslie Seidle process, to promote understanding and to contribute to their reform and Past President improvement. Judy Cedar-Wilson The constitution of the Canadian Treasurer Study of Parliament Group makes Antonine Campbell provision for various activities, including the organization of conferences and Secretary seminars in Ottawa and elsewhere in James R. Robertson Canada, the preparation of articles and various publications, the Counsellors establishment of workshops, the Dianne Brydon promotion and organization of public William Cross discussions on parliamentary affairs, David Docherty participation in public affairs programs Jeff Heynen on radio and television, and the Tranquillo Marrocco sponsorship of other educational Louis Massicotte activities. Charles Robert Jennifer Smith Membership is open to all those interested in Canadian legislative institutions. Applications for membership and additional information concerning the Group should be addressed to the Secretariat, Canadian Study of Parliament Group, Box 660, West Block, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0A6. Tel: (613) 943-1228, Fax: (613) 995- 5357. INTRODUCTION This is the fourth paper in the Canadian Study of Parliament Groups Parliamentary Perspectives. First launched in 1998, the perspective series is intended as a vehicle for distributing both studies prepared by academics and the reflections of others who have a particular interest in these themes. -

The NDP's Approach to Constitutional Issues Has Not Been Electorally

Constitutional Confusion on the Left: The NDP’s Position in Canada’s Constitutional Debates Murray Cooke [email protected] First Draft: Please do not cite without permission. Comments welcome. Paper prepared for the Annual Meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, June 2004, Winnipeg The federal New Democratic Party experienced a dramatic electoral decline in the 1990s from which it has not yet recovered. Along with difficulties managing provincial economies, the NDP was wounded by Canada’s constitutional debates. The NDP has historically struggled to present a distinctive social democratic approach to Canada’s constitution. Like its forerunner, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), the NDP has supported a liberal, (English-Canadian) nation-building approach that fits comfortably within the mainstream of Canadian political thought. At the same time, the party has prioritized economic and social polices rather than seriously addressing issues such as the deepening of democracy or the recognition of national or regional identities. Travelling without a roadmap, the constitutional debates of the 80s and 90s proved to be a veritable minefield for the NDP. Through three rounds of mega- constitutional debate (1980-82, 1987-1990, 1991-1992), the federal party leadership supported the constitutional priorities of the federal government of the day, only to be torn by disagreements from within. This paper will argue that the NDP’s division, lack of direction and confusion over constitution issues can be traced back to longstanding weaknesses in the party’s social democratic theory and strategy. First of all, the CCF- NDP embraced rather than challenged the parameters and institutions of liberal democracy. -

Steven Estey Humble Human Rights Hero

THE FaCES oF Steven Estey HumblE HuMaN Rights Hero Spotlight: Green Entrepreneurs • Taking Healthy Snacks National Community Trail Blazing • Fresh Idea Makes Waves • The Swamp Man Mailed under Canada Post Publication Mail Sales No. 40031313 | Return Undeliverable Canadian Addresses to:Alumni Office, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS B3H 3C3 FALL 2010 President’s Message 2010-2011 Alumni councIl EditoR: Fall 2010 Steve Proctor (BJ) President: Greg Poirier (MBA’03) Vice-President: Michael K. McKenzie (BComm’80) Art DirectioN and DesigN: Secretary: Mary-Evelyn Ternan (MEd’88, Spectacle Group BEd’70, BA’69) Lynn Redmond (BA’99) Past-President: Stephen Kelly (BSc’78) contributors This issue: David Carrigan (BComm’83) Brian Hayes 3 New Faces on the Alumni Council Sarah Chiasson ( MBA’06) Alan Johnson Blake Patterson 3 Alumni Outreach Program Cheryl Cook (BA’99) Suzanne Robicheau Marcel Dupupet (BComm’04) Richard Woodbury (BA Hon’04) 4 New Faces Sarah Ferguson (BComm’09) 6 Homburg Centre Breaks Ground Frank Gervais (DipEng’58) Advertising: Chandra Gosine (BA’81) (902) 420-5420 Cathy Hanrahan Cox (BA’06) Alumni DirecToR: Feature Articles Shelley Hessian (MBA’07, BComm’84) Patrick Crowley (BA’72) Omar Lodge (BComm’10) Myles McCormick (MEd’89, MA’87, BEd’77, BA’76) senioR Alumni offIcer : 8 The Faces of Steven Estey Margaret Melanson (BA’04) Kathy MacFarlane (Assoc’09) Humble Human Rights Hero could never list everything that makes me proud to be Craig Moore (BA’97) Assoc. VIcE President 11 Students Soar at the Atlantic Centre an Alumnus of Saint Mary’s University. On a weekly Ally Read (BA/BComm’07) External Affairs: basis, I hear about the difference that our family of Megan Roberts (BA’05) Margaret Murphy, (BA Hon, MA) 13 10 Cool Things I Karen Ross (BComm’77) students, professors, staff and alumni are making in a variety Wendy Sentner (BComm’01) Maroon & White is published for alumni of disciplines, media and countries. -

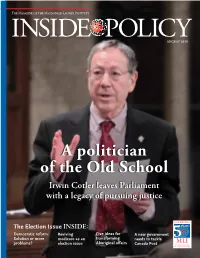

The August 2015 Issue of Inside Policy

AUGUST 2015 A politician of the Old School Irwin Cotler leaves Parliament with a legacy of pursuing justice The Election Issue INSIDE: Democratic reform: Reviving Five ideas for A new government Solution or more medicare as an transforming needs to tackle problems? election issue Aboriginal affairs Canada Post PublishedPublished by by the the Macdonald-Laurier Macdonald-Laurier Institute Institute PublishedBrianBrian Lee Lee Crowley, byCrowley, the Managing Macdonald-LaurierManaging Director,Director, [email protected] [email protected] Institute David Watson,JamesJames Anderson,Managing Anderson, Editor ManagingManaging and Editor, Editor,Communications Inside Inside Policy Policy Director Brian Lee Crowley, Managing Director, [email protected] James Anderson,ContributingContributing Managing writers:writers: Editor, Inside Policy Past contributors ThomasThomas S. AxworthyS. Axworthy ContributingAndrewAndrew Griffith writers: BenjaminBenjamin Perrin Perrin Thomas S. AxworthyDonald Barry Laura Dawson Stanley H. HarttCarin Holroyd Mike Priaro Peggy Nash DonaldThomas Barry S. Axworthy StanleyAndrew H. GriffithHartt BenjaminMike PriaroPerrin Mary-Jane Bennett Elaine Depow Dean Karalekas Linda Nazareth KenDonald Coates Barry PaulStanley Kennedy H. Hartt ColinMike Robertson Priaro Carolyn BennettKen Coates Jeremy Depow Paul KennedyPaul Kennedy Colin RobertsonGeoff Norquay Massimo Bergamini Peter DeVries Tasha Kheiriddin Benjamin Perrin Brian KenLee Crowley Coates AudreyPaul LaporteKennedy RogerColin Robinson Robertson Ken BoessenkoolBrian Lee Crowley Brian -

New NDP Vs. Classic NDP: Is a Synthesis Possible, and Does It Matter? Tom Langford

Labour / Le Travail ISSUE 85 (2020) ISSN: 1911-4842 REVIEW ESSAY / NOTE CRITIQUE New NDP vs. Classic NDP: Is a Synthesis Possible, and Does It Matter? Tom Langford David McGrane, The New NDP: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2019) Roberta Lexier, Stephanie Bangarth & Jon Weier, eds., Party of Conscience: The CCF, the NDP, and Social Democracy in Canada (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2018) Did you know that after Jack Layton took over as its leader in 2003, the federal New Democratic Party became as committed to the generation and dissemination of opposition research, or “oppo research,” as its major rivals in the federal party system? Indeed, the ndp takes the prize for being “the first federal party to set up stand alone websites specifically to attack opponents, now a common practice.”1 The ndp’s continuing embrace of “oppo research” as a means of challenging the credibility of its political rivals was on display during the final days of the 2019 federal election campaign. Facing a strong challenge from Green Party candidates in ridings in the southern part of Vancouver Island, the ndp circulated a flyer that attacked the Green Party for purportedly sharing “many Conservative values,” including being willing to “cut services [that] families need” and to fall short of “always defend[ing] the right to access a safe abortion.” Needless to say, the ndp’s claims were based on a very slanted interpretation of the evidence pulled together by its researchers 1. David McGrane, The New ndp: Moderation, Modernization, and Political Marketing (Vancouver: ubc Press, 2019), 98. -

Ten Years in the Making

ANATOMY OF THE ORANGE CRUSH: TEN YEARS IN THE MAKING Brad Lavigne It has been called an overnight success a decade in the making. The historical political realignment of federal politics by Jack Layton and the New Democratic Party was in fact an ambitious and methodical strategy to modernize Canada’s social democratic party into a viable contender for government. Brad Lavigne, the 2011 campaign manager, NDP senior strategist and longtime Jack Layton adviser, provides an insider’s account of the anatomy of the Orange Crush. Un succès instantané, certes, mais précédé d’une décennie de préparation. C’est ainsi qu’on a qualifié l’exploit de Jack Layton et du NPD, qui ont opéré un réalignement historique de la vie politique canadienne grâce à leur stratégie de modernisation ambitieuse et méthodique en vue de faire du parti social-démocrate un aspirant crédible à la direction du pays. Directeur de la campagne 2011, stratège en chef du NPD et longtemps conseiller de Jack Layton, Brad Lavigne décortique les tenants et aboutissants de la « vague orange ». t only took a few minutes. I stepped out of the makeshift It was an outcome that very few outside Jack Layton’s cir- war room in our election-night operations at the cle believed was possible and one that even fewer predicted. I Intercontinental Hotel in downtown Toronto to make a few short calls to congratulate newly elected New Democratic o how did it happen? Was it an accident? Was Jack Party (NDP) Members of Parliament from Atlantic Canada. S Layton — and the 2011 NDP campaign — simply the By the time I returned from the adjoining room, the benefactor of lacklustre performances from the Liberals and team had taped a bunch of flip-chart paper to the walls with the Bloc Québécois? Or was it something more? the names of dozens and dozens of Quebec ridings scribbled To understand how the “Orange Crush” on May 2, on them. -

The Mulroney-Schreiber Affair - Our Case for a Full Public Inquiry

HOUSE OF COMMONS CANADA THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION The Speaker of the House hereby grants permission to reproduce this document, in whole or in part for use in schools and for other purposes such as private study, research, criticism, review or newspaper summary. Any commercial or other use or reproduction of this publication requires the express prior written authorization of the Speaker of the House of Commons. If this document contains excerpts or the full text of briefs presented to the Committee, permission to reproduce these briefs, in whole or in part, must be obtained from their authors. Also available on the Parliamentary Internet Parlementaire: http://www.parl.gc.ca Available from Communication Canada — Publishing, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0S9 THE MULRONEY-SCHREIBER AFFAIR - OUR CASE FOR A FULL PUBLIC INQUIRY Report of the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics Paul Szabo, MP Chair APRIL, 2008 39th PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION STANDING COMMITTEE ON ACCESS TO INFORMATION, PRIVACY AND ETHICS Paul Szabo Pat Martin Chair David Tilson Liberal Vice-Chair Vice-Chair New Democratic Conservative Dean Del Mastro Sukh Dhaliwal Russ Hiebert Conservative Liberal Conservative Hon. Charles Hubbard Carole Lavallée Richard Nadeau Liberal Bloc québécois Bloc québécois Glen Douglas Pearson David Van Kesteren Mike Wallace Liberal Conservative Conservative iii OTHER MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT WHO PARTICIPATED Bill Casey John Maloney Joe Comartin Hon. Diane Marleau Patricia Davidson Alexa McDonough Hon. Ken Dryden Serge Ménard Hon. -

International Day of the Girl Child Published By

International Day of the Girl Child Published by 5450 Cornwallis Street, Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3K 1A9 Written by El Jones Illustrated by Bria Cherise Miller ISBN 978-0-9949292-7-3 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Printed in Nova Scotia Copyright © 2018 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency. Why is there an international day of the girl? Because we know girls are powerful, courageous, creative and they are making a difference in communities everywhere. You don’t have to wait until you become a woman to make a differ- ence. You can make a difference in many ways, large or small. Girls all over the world face challenges and discrimination. They are not always given access to knowledge, skills, protection, and support. This day is a reminder that girls need to be treated equitably and recognized for their potential. There is no future without girls. We should all champion girls and women around us. Learn about the good, brave and beautiful things girls are doing here and around the world for their families, schools, friends, communities, the environment and more. Recognize and honour girls, past and present. The world needs to hear girls’ stories in the media, in the movies, in books, the school curriculum, and in poems. We hope you enjoy this poem, written by El Jones and illustrated by Bria Miller, now in its second printing! We hope you share it with a friend, too. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents RE-INVENTING THE LEFT IN CANADA Introduction........................................................................................................ 31 A Party in Crisis?..................................................................................................33 The Informed Viewer ..........................................................................................34 Canadian Social Democratic Movement Overview ..............................................35 Fortune and Men’s Eyes ...................................................................................... 39 Discussion, Research, and Essay Questions ..........................................................43 RE-INVENTING THE LEFT IN CANADA Introduction After a disappointing showing in the Novem- deficits, there is increased public support for ber 2000 federal election, its third since a halt to further cuts to spending in educa- 1993, the federal New Democratic Party tion, health, and social programs, and a faces serious challenges as it contemplates its reinvestment of tax revenues into these vital political future. Under the leadership of areas. Alexa McDonough, the NDP’s campaign Such trends should offer a promising focused directly on what all the opinion polls environment for the NDP and its social indicated was the primary concern of Cana- reform message, yet in three successive dians: the preservation of the country’s federal elections the party has been relegated publicly funded health-care system. Despite to an increasingly marginal position in the NDP’s often-repeated claims that as the Canadian federal politics. In fact, during the party responsible for introducing medicare in last campaign most media coverage was Canada it could best be counted on to defend devoted to what were viewed as the only two the system from further cuts, only eight per parties that could realistically claim to be cent those who voted in the election gave it serious contenders for power—the Liberals their support. The NDP’s total representation and the Canadian Alliance. -

International Women's

IWD 2013 INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY JOIN US FOR A FREE POTLUCK TO CELEBRATE STRONG WOMEN. Together, we’re changing the fACE OF POWER IN CANADA. Thursday, March 7, 2013, 5:30 - 8:00 p.m. Kerby Centre (1133 7th Ave SW) Guest Speaker: Gael McLeod, Calgary City Alderman Ward 5. Entertainment by Elbow River & The Raging Grannies. RSVP at 403-264-1155 or [email protected]. Visit womenscentrecalgary.org. *THE EVENT IS A POTLUCK SO PLEASE BRING A FOOD ITEM. This event is brought to you by the International Women’s Day Planning Committee: INTERNATIONAL WOMEN’S DAY From top left, on front: VIOLET MCNAUGHTON - A leader in the Canadian farm, women’s, peace, and co-operative movements. She became the most influential farm woman in Canada and in Saskatchewan during the first half of the 20th century. KIM CAMPBELL - A Canadian politician, lawyer, university professor, diplomat, and writer. She served as the 19th Prime Minister of Canada, from June 25, 1993 to November 4, 1993. Campbell was the first, and to date, the only female Prime Minister of Canada, the first baby boomer to hold that office, and the only Prime Minister to have been born in British Columbia. ADRIENNE CLARKSON – A Canadian journalist and stateswoman who served as the 26th Governor General of Canada, the second female to hold the position since Canadian Confederation, from 1999-2005 NYCOLE TURMEL – Former PSAC National President and current Canadian Member of Parliament. When Jack Layton died on August 22, 2011, Turmel became Leader of the Official Opposition, the second woman to be so appointed, until the selection of Thomas Mulcair in the 2012 leadership election on March 24, 2012. -

Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian

Keghart Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian Genocide Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/just-poems-reflections-on-the-armenian-genocide/ and Democracy JUST POEMS: REFLECTIONS ON THE ARMENIAN GENOCIDE Posted on August 25, 2009 by Keghart Category: Opinions Page: 1 Keghart Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian Genocide Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/just-poems-reflections-on-the-armenian-genocide/ and Democracy By Professor Alan Whitehorn, Canada, August 2009 Prof. Alan Whitehorn has taught in the areas of Canadian parties and public opinion, comparative politics and political theory at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario for over three decades. His latest book is 'Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian Genocide' (Winnipeg, Hybrid, 2009). He is well connected with the Armenian Community in Canada. Each summer he regularly visits Armenia for vacationing and research. He extensively takes part in the various workshops organized by the Zoryan Institute, and he was one of the panelists of public discussion devoted to Policy Directions in Post-Election Armenia in Montreal - 20 June 2008 (View a video clip below). The following is a summary of Prof. Whitehorn's achievements tramscribed from the Website of the Canadian National Defence - Royal Military College of Canada By Professor Alan Whitehorn, Canada, August 2009 Prof. Alan Whitehorn has taught in the areas of Canadian parties and public opinion, comparative politics and political theory at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario for over three decades. His latest book is 'Just Poems: Reflections on the Armenian Genocide' (Winnipeg, Hybrid, 2009). -

FEBRUARY 2003 Graham Fraser

THE NDP LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE—RE-CONNECTING THE LEFT TO THE MIDDLE In the run-up to the NDP leadership vote on January 25, party activists faced a difficult choice between two apparent front runners, the well known face of NDP House Leader Bill Blaikie of Manitoba, and Toronto city councillor Jack Layton, an interesting new face with national credentials as president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities. While Blaikie represents the party’s deep roots in the West and the co-operative movement, Layton represents the possibility of taking the NDP back into the cities and union towns of southern Ontario, where it was strong during the era of Ed Broadbent from 1975-1988, a highwater mark in NDP history. Toronto Star columnist Graham Fraser, widely acclaimed for his books on Canadian politics, offers this situational update on a party confronting an agonizing choice. Graham Fraser En prévision du scrutin à la direction du Nouveau Parti Démocratique du 25 janvier, les militants font face à un choix difficile entre les deux candidats les plus en vue : le Manitobain Bill Blaikie, leader du NPD à la Chambre des communes, et Jack Layton, conseiller municipal de la ville de Toronto et un temps président de la Fédération canadienne des municipalités. Un premier visage très connu, donc, et un second qui gagne à l’être. Si Blaikie représente le profond enracinement du parti dans l’Ouest du pays et le mouvement coopératif, Layton incarne pour sa part l’espoir de lui rendre la popularité dont il jouissait dans les grands centres et les villes ouvrières du sud de l’Ontario, où le NPD a connu une période historiquement fastueuse sous le règne d’Ed Broadbent, de 1975 à 1988.