Cover Songs: Metaphor Or Object of Study?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Full Results of Survey of Songs

Existential Songs Full results Supplementary material for Mick Cooper’s Existential psychotherapy and counselling: Contributions to a pluralistic practice (Sage, 2015), Appendix. One of the great strengths of existential philosophy is that it stretches far beyond psychotherapy and counselling; into art, literature and many other forms of popular culture. This means that there are many – including films, novels and songs that convey the key messages of existentialism. These may be useful for trainees of existential therapy, and also as recommendations for clients to deepen an understanding of this way of seeing the world. In order to identify the most helpful resources, an online survey was conducted in the summer of 2014 to identify the key existential films, books and novels. Invites were sent out via email to existential training institutes and societies, and through social media. Participants were invited to nominate up to three of each art media that ‘most strongly communicate the core messages of existentialism’. In total, 119 people took part in the survey (i.e., gave one or more response). Approximately half were female (n = 57) and half were male (n = 56), with one of other gender. The average age was 47 years old (range 26–89). The participants were primarily distributed across the UK (n = 37), continental Europe (n = 34), North America (n = 24), Australia (n = 15) and Asia (n = 6). Around 90% of the respondents were either qualified therapists (n = 78) or in training (n = 26). Of these, around two-thirds (n = 69) considered themselves existential therapists, and one third (n = 32) did not. There were 235 nominations for the key existential song, with enormous variation across the different respondents. -

Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository August 2016 Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music Briana E. Morley The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Keir Keightley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts © Briana E. Morley 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Morley, Briana E., "Not In "Isolation": Joy Division and Cultural Collaborators in Popular Music" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3991. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3991 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Abstract There is a dark mythology surrounding the post-punk band Joy Division that tends to foreground the personal history of lead singer Ian Curtis. However, when evaluating the construction of Joy Division’s public image, the contributions of several other important figures must be addressed. This thesis shifts focus onto the peripheral figures who played key roles in the construction and perpetuation of Joy Division’s image. The roles of graphic designer Peter Saville, of television presenter and Factory Records founder Tony Wilson, and of photographers Kevin Cummins and Anton Corbijn will stand as examples in this discussion of cultural intermediaries and collaborators in popular music. -

Precious but Not Precious UP-RE-CYCLING

The sounds of ideas forming , Volume 3 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2020 presents precious but not precious UP-RE-CYCLING This is the recycle tip at Clatterbridge. In February 2020, we’re dropping off some stuff when Brigitte shouts “if you get to the plastic section sharpish, someone’s throwing out a pile of records.” I leg it round and within seconds, eyes and brain honed from years in dank backrooms and charity shops, I smell good stuff. I lean inside, grabbing a pile of vinyl and sticking it up my top. There’s compilations with Blondie, Boomtown Rats and Devo and a couple of odd 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters soundtracks. COVER (VERSIONS) www.alandunn67.co.uk/coverversions.html For those that read the last text, you’ll enjoy the irony in this introduction. This story is about vinyl but not as a precious and passive hands-off medium but about using it to generate and form ideas, abusing it to paginate a digital sketchbook and continuing to be astonished by its magic. We re-enter the story, the story of the sounds of ideas forming, after the COVER (VERSIONS) exhibition in collaboration with Aidan Winterburn that brings together the ideas from July 2018 – December 2019. Staged at Leeds Beckett University, it presents the greatest hits of the first 18 months and some extracts from that first text that Aidan responds to (https://tinyurl.com/y4tza6jq), with me in turn responding back, via some ‘OUR PRICE’ style stickers with quotes/stats. For the exhibition, the mock-up sleeves fabricated by Tom Rodgers look stunning, turning the digital detournements into believable double-sided artefacts. -

The DIY Careers of Techno and Drum 'N' Bass Djs in Vienna

Cross-Dressing to Backbeats: The Status of the Electroclash Producer and the Politics of Electronic Music Feature Article David Madden Concordia University (Canada) Abstract Addressing the international emergence of electroclash at the turn of the millenium, this article investigates the distinct character of the genre and its related production practices, both in and out of the studio. Electroclash combines the extended pulsing sections of techno, house and other dance musics with the trashier energy of rock and new wave. The genre signals an attempt to reinvigorate dance music with a sense of sexuality, personality and irony. Electroclash also emphasizes, rather than hides, the European, trashy elements of electronic dance music. The coming together of rock and electro is examined vis-à-vis the ongoing changing sociality of music production/ distribution and the changing role of the producer. Numerous women, whether as solo producers, or in the context of collaborative groups, significantly contributed to shaping the aesthetics and production practices of electroclash, an anomaly in the history of popular music and electronic music, where the role of the producer has typically been associated with men. These changes are discussed in relation to the way electroclash producers Peaches, Le Tigre, Chicks on Speed, and Miss Kittin and the Hacker often used a hybrid approach to production that involves the integration of new(er) technologies, such as laptops containing various audio production softwares with older, inexpensive keyboards, microphones, samplers and drum machines to achieve the ironic backbeat laden hybrid electro-rock sound. Keywords: electroclash; music producers; studio production; gender; electro; electronic dance music Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 4(2): 27–47 ISSN 1947-5403 ©2011 Dancecult http://dj.dancecult.net DOI: 10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.02.02 28 Dancecult 4(2) David Madden is a PhD Candidate (A.B.D.) in Communications at Concordia University (Montreal, QC). -

Culture Vulture 2011

Culture Vulture 2011 PJ Harvey – Let England Speak (CD + DVD) White Denim – D Bon Iver – Bon Iver Elbow – Build A Rocket Boys! Vinicio Caposella – Marinai, Profeti e Balene (2CD) Spinvis & Hanco Kolk – Tot Ziens, Justine Keller (CD + boek) King Creosote & Jon Hopkins – Diamond Mine DeWolff – Orchards/Lupine Kiran Ahluwalia – Aam Zameen: Common Ground Lucas Santtana – Sem Nostalgia Chris Chameleon – As Jy Weer Skryf Raghu Dixit – Raghu Dixit The Amazing – Gentle Stream Danger Mouse & Daniele Luppi – Rome Nils Frahm – Felt Raphael Saadiq – Stone Rollin’ June Tabor & Oysterband – Ragged Kingdom Ry Cooder – Pull Up Some Dust And Sit Down Patrick Wolf – Lupercalia Gruff Rhys – Hotel Shampoo Samenstelling: Hans Verbakel (4.1.2012) Culture Vulture 2011 100 shorts De eerste twintig zijn favoriete nummers van mijn album top 20. De resterende tachtig staan in “redelijk” willekeurige shuffle volgorde. PJ Harvey – The Words That Maketh Murder Tom Russell – Farewell Never Never Land White Denim – River To Consider Tim Knol – Days Bon Iver – Holocene Beirut – East Harlem Elbow – Lippy Kids Aaron Wright – Trampoline Vinicio Caposella – Lord Jim The Middle East – Hunger Song Spinvis – Kom Terug Thurston Moore – Benediction King Creosote & Jon Hopkins – Bats In The Attic Kurt Vile – Ghost Town DeWolff – Everything Everywhere Nicolas Jaar – Too Many Kids Finding Rain In The Dust Kiran Ahluwalia – Saffar Radiohead – Codex Lucas Santtana – Super Violão Mashup Adele – Someone Like You Chris Chameleon – Daar Is Net Een Vir Altyd Jessie J (feat. B.o.B.) – Price Tag Raghu Dixit – In Mumbai, Waiting for a Miracle Iness Mezel – Amazone The Amazing – Flashlight Dengue Fever – Mr Bubbles Danger Mouse & Daniele Luppi feat. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

Adjagas to Open Glastonbury - Listen to Norway 14.07.10 01.28

Adjagas to open Glastonbury - Listen to Norway 14.07.10 01.28 search articles search directory HOME BALLADE DIRECTORY CALENDAR MUSIC STORE SHEET MUSIC CATALOGUE CONTACT TEXT ARCHIVE IAMIC ABOUT MIC PÅ NORSK Adjagas to open Glastonbury MIC Music The opening of this year’s Glasto will be truly special: Information Lapland’s Adjagas kick off the massive festival with their Centre Norway opening slot at the main stage. Like 205 21.02.2007 | By: Tomas Lauvland Pettersen MIC Music Adjagas were originally booked to Information Centre open Glastonbury in 2005 but that Norway The Quietus year’s torrential rains put an end talks to Jørgen to their show before the duo had Munkeby of Shining: even hit the stage. Now the Sámi outfit is scheduled to return to the The Quietus | Features | major festival’s main stage in 2010 A Glass order to kick-start Glasto 2007 on Half Full | Sax 22 June. And Violence: Jørgen Strong UK reviews Munkeby of Adjagas has garnered rave Shining Interv reviews in the domestic press for thequietus.com their self-titled debut album A new rock released in Norway last year through Trust Me Records. Now the release has been music and pop licensed to !K7 subsidiary Ever Records which launched the album on the European culture market in January 2007. The outfit’s unique take on the traditional Sámi vocal style, website. Editorial joik, which is fused with more contemporary influences has struck a chord with UK independent critics and the first batch of reviews are indeed positive. A few excerpts: “The current folk revival has brought many maverick sounds into the mainstream. -

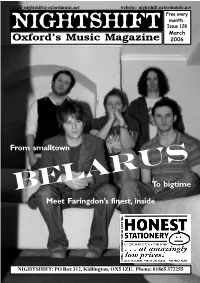

[email protected] Website: Nightshift.Oxfordmusic.Net Free Every Month

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 128 March Oxford’s Music Magazine 2006 From smalltown belarusTo bigtime Meet Faringdon’s finest, inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] LOCAL BANDS have until March 15th to City Girl. This year’s line-up will be announced submit demos for this year’s Oxford Punt. The on the Nightshift website noticeboard and on Punt, organised by Nightshift Magazine, takes Oxfordbands.com on March 16th. place across six venues in Oxford city centre on All-venue Punt passes are now on sale from Wednesday 10th May and will showcase 18 of Polar Bear Records on Cowley Road or online the best new unsigned bands and artists in the from oxfordmusic.net. As ever there will only county. Bands and solo acts can send demos, be 100 passes available, priced at £7 each (plus clearly marked The Punt, to Nightshift, PO Box booking fee). 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Bands who have previously made their reputations early on at TRUCK FESTIVAL 2006 tickets are now on the Punt include The Young Knives and Fell sale nationally after being made available to Oxfordshire music fans only at the start of STEVE GORE February. Tickets for the two-day festival at Hill Farm, Steventon over the weekend of the GARY NUMAN plays his first Oxford show 1965-2006 22nd and 23rd July are priced at £40 and are on for 12 years when he appears at Brookes th Steve Gore, bass player with local ska-punk sale from the Zodiac box office, Polar Bear University Union on Sunday 30 April. -

JOY DIVISION Re-Releases På Vinyl På Mandag D. 29. Juni !

2015-06-23 12:36 CEST JOY DIVISION re-releases på vinyl på mandag d. 29. juni ! Rhino will reissue Joy Division‘s two studio albums Unknown Pleasures andCloser on vinyl, followed closely by similar vinyl re-releases of compilations Still and Substance (with the latter newly expanded). All these 180g records use the 2007 remasters except Substance which uses a 2010 remastering. Both Still and Substance will be gatefold two-LP sets and for the first time on vinyl, the expanded track listing from the original CD release of Substance is used here PLUS plus two additional songs: As You Said and the Pennine version ofLove Will Tear Us Apart. This 19-track version will also be issued on CD. Rhino have promised that “each design replicates the original in painstaking detail”andUnknown Pleasures and Closer will be re-released on 29 June with the two vinyl compilations and the new CD edition of Substance following on July 24 2015. Track listing Unknown Pleasures Side A 1. “Disorder” 2. “Day of the Lords” 3. “Candidate” 4. “Insight” 5. “New Dawn Fades” Side B 1. “She’s Lost Control” 2. “Shadowplay” 3. “Wilderness” 4. “Interzone” 5. “I Remember Nothing” Closer Side A 1. “Atrocity Exhibition” 2. “Isolation” 3. “Passover” 4. “Colony” 5. “A Means to an End” Side B 1. “Heart and Soul” 2. “Twenty Four Hours” 3. “The Eternal” 4. “Decades” Still (2LP) Side A 1. “Exercise One” 2. “Ice Age” 3. “The Sound of Music” 4. “Glass” 5. “The Only Mistake” Side B 1. “Walked in Line” 2. -

A Musicological and Theological Analysis of Sufjan Stevens's Song, "Christmas Unicorn"

ABSTRACT I'm a Christmas Unicorn: A musicological and theological analysis of Sufjan Stevens's song, "Christmas Unicorn" Janna Martindale Director: Jean Boyd, Ph.D. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce the reader to Sufjan Stevens’s 2012 fifty- eight track album Silver & Gold, and specifically the final song, “Christmas Unicorn,” a twelve and half minute anti-epic pop song that starts off in a folk style and builds to an electronic, symphonic climax. The album presents many styles of Christmas songs, including Bach chorales, hymns, original songs, “Jingle Bells,” and a Prince cover. I argue that this album is a post-modern presentation demonstrating all the different expressions of Christmas are valid, no matter how commercial or humble. “Christmas Unicorn” synthesizes all these styles through the metaphor of the unicorn, which is a medieval symbol of Christ in the Nativity and the Crucifixion. Stevens uses the symbol of the unicorn to represent Christ as well as all humans and all the different attributes of Christmas. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: __________________________________________ Dr. Jean Boyd, Department of School of Music APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ___________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Director DATE: __________________________________ I’M A CHRISTMAS UNICORN: A MUSICOLOGICAL AND THEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF SUFJAN STEVEN’S SONG, “CHRISTMAS UNICORN” A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Janna Martindale Waco, Texas ! TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter One: Introduction . 1 Chapter Two: Biography of Sufjan Stevens . 7 Chapter Three: Silver and Gold . 19 Chapter Four: Symbolism of the Unicorn . -

For a Lark the Poetry of Songs

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS PROGRAMA EM TEORIA DA LITERATURA FOR A LARK THE POETRY OF SONGS Telmo Rodrigues DOUTORAMENTO EM ESTUDOS DE LITERATURA E DE CULTURA TEORIA DA LITERATURA 2014 Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras Programa em Teoria da Literatura FOR A LARK THE POETRY OF SONGS Telmo Rodrigues Dissertação orientada por: PROFESSOR DOUTOR ANTÓNIO M. FEIJÓ PROFESSOR DOUTOR MIGUEL TAMEN Doutoramento em Estudos de Literatura e de Cultura Teoria da Literatura 2014 Acknowledgments The work for this thesis was done under a fellowship granted by the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT): the time granted to think is priceless, and I am indeed thankful for being allowed to benefit from it. During this period I have also benefited from the resources put at my disposal by my host institution, the Nova Institute of Philosophy (IFILNOVA). Professor António Feijó has been teaching me since my first year of undergraduate studies and Professor Miguel Tamen since I started graduate studies: I am still to this day amazed at the luck I have for being given the opportunity to work with both of them, and my gratitude for their efforts and enthusiasm in crafting this thesis is immeasurable. As a student of the Program in Literary Theory I must extend my thanks to Professor João Figueiredo, who is an integral part of the Program and with whom I have learnt many valuable things about art. When writing a thesis, a friend who enjoys editing is a blessing one must always be thankful for; in any case, I would gladly dismiss Helena’s editing skills for the friendship which has shaped this work beyond recognition and, necessarily, beyond any written acknowledgment.