Examining Migration, Livelihoods, and HIV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20210714 Access Snapshot- Tigray Region June 2021 V2

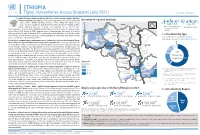

ETHIOPIA Tigray: Humanitarian Access Snapshot (July 2021) As of 31 July 2021 The conflict in Tigray continues despite the unilateral ceasefire announced by the Ethiopian Federal Government on 28 June, which resulted in the withdrawal of the Ethiopian National Overview of reported incidents July Since Nov July Since Nov Defense Forces (ENDF) and Eritrea’s Defense Forces (ErDF) from Tigray. In July, Tigray forces (TF) engaged in a military offensive in boundary areas of Amhara and Afar ERITREA 13 153 2 14 regions, displacing thousands of people and impacting access into the area. #Incidents impacting Aid workers killed Federal authorities announced the mobilization of armed forces from other regions. The Amhara region the security of aid Tahtay North workers Special Forces (ASF), backed by ENDF, maintain control of Western zone, with reports of a military Adiyabo Setit Humera Western build-up on both sides of the Tekezi river. ErDF are reportedly positioned in border areas of Eritrea and in SUDAN Kafta Humera Indasilassie % of incidents by type some kebeles in North-Western and Eastern zones. Thousands of people have been displaced from town Central Eastern these areas into Shire city, North-Western zone. In line with the Access Monitoring and Western Korarit https://bit.ly/3vcab7e May Reporting Framework: Electricity, telecommunications, and banking services continue to be disconnected throughout Tigray, Gaba Wukro Welkait TIGRAY 2% while commercial cargo and flights into the region remain suspended. This is having a major impact on Tselemti Abi Adi town May Tsebri relief operations. Partners are having to scale down operations and reduce movements due to the lack Dansha town town Mekelle AFAR 4% of fuel. -

Amhara Claim of Western and Southern Parts of Tigray

AMHARA CLAIM OF WESTERN AND SOUTHERN PARTS OF TIGRAY By Mathza 11-26-20 We have been hearing and reading about the Amhara Regional State claim of ownership of the Welqayit, Tsegede, Qafta-Humera and Tselemti weredas (hereafter refereed to Welqayit Group) and Raya, and Amhara Regional State threats of war against TPLF/Tigray. One of the threats states “some of the Amhara elite politicians continue to beat drums, as summons to war” (watch/listen) DW TV (Amharic) - July 30, 2020. THE WELQAYIT GROUP Welkayit Amhara Identity Committee (WAIC) was formed in Gonder to return the Welqayit Group from Tigray Regional State to Amhara Regional State. The Welqayit Group was transferred to Tigray during the 1984 reconfiguration of the administrative structure of the country based on ethno-linguistical regional states (kililoch) after the Derg was defeated. It seems that the government of Eritrea has contributed to the Welqayit Group problem. According to ህግደፍንኣሸበርቲ ጉጅለታትን ብአንደበት…ቀዳማይ ክፋል (watch) the Eritrean government had trained Ethiopian oppositions and inculcated opposing views between ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly between Amhara and Tigray Regional States, wherever it viewed appropriate for its devilish objective of dismantling Ethiopia. The Committee recruited Tigrayans from Tigray Regional State to do its dirty work. An example is presented in a video, Tigrai Tv:መድረኽተሃድሶ ወረዳ ቃፍታ- ሑመራህዝቢ ጣብያ ዓዲ-ሕርዲ - YouTube (watch) aired on Feb 01, 2017. It shows confessions by a number of Tigrayans from Qafta-Humera who were lured and bribed by the Committee to serve its objectives. Each of them gave details of activities they participated in and carried out against their own people. -

Regreening of the Northern Ethiopian Mountains: Effects on Flooding and on Water Balance

PATRICK VAN DAMME THE ROLE OF TREE DOMESTICATION IN GREEN MARKET PRODUCT VALUE CHAIN DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA afrika focus — Volume 31, Nr. 2, 2018 — pp. 129-147 REGREENING OF THE NORTHERN ETHIOPIAN MOUNTAINS: EFFECTS ON FLOODING AND ON WATER BALANCE Tesfaalem G. Asfaha (1,2), Michiel De Meyere (2), Amaury Frankl (2), Mitiku Haile (3), Jan Nyssen (2) (1) Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Mekelle University, Ethiopia (2) Department of Geography, Ghent University, Belgium (3) Department of Land Resources Management and Environmental Protection, Mekelle University, Ethiopia The hydro-geomorphology of mountain catchments is mainly determined by vegetation cover. This study was carried out to analyse the impact of vegetation cover dynamics on flooding and water balance in 11 steep (0.27-0.65 m m-1) catchments of the western Rift Valley escarpment of Northern Ethiopia, an area that experienced severe deforestation and degradation until the first half of the 1980s and considerable reforestation thereafter. Land cover change analysis was carried out using aerial photos (1936,1965 and 1986) and Google Earth imaging (2005 and 2014). Peak discharge heights of 332 events and the median diameter of the 10 coarsest bedload particles (Max10) moved in each event in three rainy seasons (2012-2014) were monitored. The result indicates a strong re- duction in flooding (R2 = 0.85, P<0.01) and bedload sediment supply (R2 = 0.58, P<0.05) with increas- ing vegetation cover. Overall, this study demonstrates that in reforesting steep tropical mountain catchments, magnitude of flooding, water balance and bedload movement is strongly determined by vegetation cover dynamics. -

Democracy Under Threat in Ethiopia Hearing Committee

DEMOCRACY UNDER THREAT IN ETHIOPIA HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HEALTH, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS, AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 9, 2017 Serial No. 115–9 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Affairs ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.foreignaffairs.house.gov/ or http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 24–585PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 0ct 09 2002 11:13 Apr 20, 2017 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\_AGH\030917\24585 SHIRL COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS EDWARD R. ROYCE, California, Chairman CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida BRAD SHERMAN, California DANA ROHRABACHER, California GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ALBIO SIRES, New Jersey JOE WILSON, South Carolina GERALD E. CONNOLLY, Virginia MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas THEODORE E. DEUTCH, Florida TED POE, Texas KAREN BASS, California DARRELL E. ISSA, California WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania DAVID N. CICILLINE, Rhode Island JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina AMI BERA, California MO BROOKS, Alabama LOIS FRANKEL, Florida PAUL COOK, California TULSI GABBARD, Hawaii SCOTT PERRY, Pennsylvania JOAQUIN CASTRO, Texas RON DESANTIS, Florida ROBIN L. KELLY, Illinois MARK MEADOWS, North Carolina BRENDAN F. BOYLE, Pennsylvania TED S. -

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies Local use of spices, condiments and non-edible oil crops in some selected woredas in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. A Thesis submitted to the school of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biology (Dryland Biodiversity). By Atey G/Medhin November /2008 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Acknowledgements I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisors Drs. Tamirat Bekele and Tesfaye Bekele for their consistent invaluable advice, comments and follow up from problem identification up to the completion of this work. The technical staff members of the National Herbarium (ETH) are also acknowledged for rendering me with valuable services. I am grateful to the local people, the office of the woredas administration and agricultural departments, chairpersons and development agents of each kebele selected as study site. Thanks also goes to Tigray Regional State Education Bureau for sponsoring my postgraduate study. I thank the Department of Biology, Addis Ababa University, for the financial support and recommendation letters it offered me to different organizations that enabled me to carry out the research and gather relevant data. Last but not least, I am very much indebted to my family for the moral support and encouragement that they offered to me in the course of this study. I Acronyms and Abbreviations BoARD Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Development CSA Central Statistics Authority EEPA Ethiopian Export Promotion -

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia

Linking Poor Rural Households to Microfinance and Markets in Ethiopia Baseline and Mid-term Assessment of the PSNP Plus Project in Raya Azebo November 2010 John Burns & Solomon Bogale Longitudinal Impact Study of the PSNP Plus Program Baseline Assessment in Raya Azebo Table of Contents SUMMARY 6 1. INTRODUCTION 8 1.1 PSNP PLUS PROJECT BACKGROUND 8 1.2 LINKING POOR RURAL HOUSEHOLDS TO MICROFINANCE AND MARKETS IN ETHIOPIA. 9 2 THE PSNP PLUS PROJECT 10 2.1 PSNP PLUS OVERVIEW 10 2.2 STUDY OVERVIEW 11 2.3 OVERVIEW OF PSNP PLUS PROJECT APPROACH IN RAYA AZEBO 12 2.3.1 STUDY AREA GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS 12 2.3.2 MICROFINANCE LINKAGE COMPONENT 12 2.3.3 VILLAGE SAVINGS AND LOAN ASSOCIATIONS 13 2.3.4 MARKET LINKAGE COMPONENT 14 2.3.5 IMPLEMENTATION CHALLENGES 17 2.4 RESEARCH QUESTIONS 18 3. ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY 19 3.1 STUDY APPROACH 19 3.2 OVERVIEW OF METHODS AND INDICATORS 19 3.3 INDICATOR SELECTION 20 3.4 SAMPLING 20 3.4.1 METHOD AND SIZE 20 3.4.2 STUDY LOCATIONS 21 3.5 DATA COLLECTION METHODS 22 3.5.1 HOUSEHOLD INTERVIEWS 22 3.5.2 FOCUS GROUP METHODS 22 3.6 PRE-TESTING 23 3.7 TRIANGULATION AND VALIDATION 23 3.8 DATA ANALYSIS 23 4 RESULTS 25 4.1 CONTEXTUALIZING PSNP PLUS 25 4.2 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND STATUS AT THE TIME OF THE ASSESSMENT 26 4.3 IMPACT OF THE DROUGHT IN 2009 28 4.4 COMMUNITY CHARACTERISTICS 29 4.5 INCOME AND EXPENDITURE 30 4.5.1 PROJECT DERIVED INCOME AND UTILIZATION 31 4.6 SAVINGS AND LOANS 33 4.6.1 PSNP PLUS VILLAGE SAVINGS GROUPS 34 4.7 ASSETS AND ASSET CHANGES 35 4.8. -

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary

FEWS NET Ethiopia Trip Report Summary Activity Name: Belg 2015 Mid-term WFP and FEWS NET Joint assessment Reported by: Zerihun Mekuria (FEWS NET) and Muluye Meresa (WFP_Mekelle), Dates of travel: 20 to 22 April 2015 Area Visited: Ofla, Raya Alamata and Raya Azebo Woredas in South Tigray zones Reporting date: 05 May 2015 Highlights of the findings: Despite very few shower rains in mid-January, the onset of February to May Belg 2015 rains delayed by more than six weeks in mid-March and most Belg receiving areas received four to five days rains with amount ranging low to heavy. It has remained drier and warmer since 3rd decade of March for more than one month. Most planting has been carried out in mid-March except in few pocket areas in the highlands that has planted in January. About 54% of the normal Belg area has been covered with Belg crops. Planted crops are at very vegetative stage with significant seeds remained aborted in the highlands. While in the lowlands nearly entire field planted with crop is dried up or wilted. Dryness in the Belg season has also affected the land preparation and planting for long cycle sorghum. Although the planting window for sorghum not yet over, prolonged dryness will likely lead farmers to opt for planting low yielding sorghum variety. Average Meher 2014 production has improved livestock feed availability. The crop residue reserve from the Meher harvest is not yet exhausted. Water availability for livestock is normal except in five to seven kebeles in Raya Azebo woreda that has faced some water shortages for livestock. -

SITUATION ANALYSIS of CHILDREN and WOMEN: Tigray Region

SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: Tigray Region This briefing note covers several issues related to child well-being in Tigray Regional State. It builds on existing research and the inputs of UNICEF Ethiopia sections and partners.1 It follows the structure of the Template Outline for Regional Situation Analyses. 1Most of the data included in this briefing note comes from the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), Household Consumption and Expenditure Survey (HCES), Education Statistics Annual Abstract (ESAA) and Welfare Monitoring Survey (WMS) so that a valid comparison can be made with the other regions of Ethiopia. SITUATION ANALYSIS OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN: TIGRAY REGION 4 1 THE DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT The northern and mountainous region of Tigray has an estimated population of 5.4 million people, of which approximately 13 per cent are under 5 years old and 43 per cent is under 18 years of age. This makes Tigray the fifth most populous region of Ethiopia. Tigray has a relatively high percentage of female-headed households, at 34 per cent in 2018 versus a national rate of 25 per cent in 2016. Three out of four Tigrayans live in rural areas, and most depend on agriculture (mainly subsistence crop farming).4 Urbanization is an emerging priority, as many new towns are created, and existing towns expand. Urbanization in Tigray is referred to as ‘aggressive’, with an annual rate of 4.6 per cent in the Tigray Socio-Economic Baseline Survey Report (2018).5 The annual urban growth -

Ethiopia: Access

ETHIOPIA Access Map - Tigray Region As of 31 May 2021 ERITREA Ethiopia Adi Hageray Seyemti Egela Zala Ambesa Dawuhan Adi Hageray Adyabo Gerhu Sernay Gulo Mekeda Erob Adi Nebried Sheraro Rama Ahsea Tahtay Fatsi Eastern Tahtay Adiyabo Chila Rama Adi Daero Koraro Aheferom Saesie Humera Chila Bzet Adigrat Laelay Adiabo Inticho Tahtay Selekleka Laelay Ganta SUDAN Adwa Edaga Hamus Koraro Maychew Feresmay Afeshum Kafta Humera North Western Wukro Adwa Hahayle Selekleka Akxum Nebelat Tsaeda Emba Shire Embaseneyti Frewoyni Asgede Tahtay Edaga Arbi Mayechew Endabaguna Central Hawzen Atsbi May Kadra Zana Mayknetal Korarit TIGRAY Naeder Endafelasi Hawzen Kelete Western Zana Semema Awelallo Tsimbla Atsibi Adet Adi Remets Keyhe tekli Geraleta Welkait Wukro May Gaba Dima Degua Tsegede Temben Dima Kola Temben Agulae Awra Tselemti Abi Adi Hagere May Tsebri Selam Dansha Tanqua Dansha Melashe Mekelle Tsegede Ketema Nigus Abergele AFAR Saharti Enderta Gijet AMHARA Mearay South Eastern Adi Gudom Hintalo Samre Hiwane Samre Wajirat Selewa Town Accessible areas Emba Alaje Regional Capital Bora Partially accessible areas Maychew Zonal Capital Mokoni Neqsege Endamehoni Raya Azebo Woreda Capital Hard to reach areas Boundary Accessible roads Southern Chercher International Zata Oa Partially accessible roads Korem N Chercher Region Hard to reach roads Alamata Zone Raya Alamata Displacement trends 50 Km Woreda The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 31 May 2021 Sources: OCHA, Tigray Statistical Agency, humanitarian partners Feedback: [email protected] http://www.humanitarianresponse.info/operations/ethiopia www.reliefweb.int. -

S P E C I a L R E P O

S P E C I A L R E P O R T FAO/WFP CROP AND FOOD SUPPLY ASSESSMENT MISSION TO ETHIOPIA 24 February 2006 FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, ROME WORLD FOOD PROGRAMME, ROME - ii - This report has been prepared by Mr. W.I. Robinson and Mr. A.T. Lieberg and Ms. L. Trebbi, under the responsibility of the FAO and WFP Secretariats with information from official and other sources. Since conditions may change rapidly, please contact the undersigned for further information if required. Henri Josserand Holdbrook Arthur Chief, GIEWS, FAO Regional Director, ODK WFP Fax: 0039-06-5705-4495 Fax: 00256-31242500 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Please note that this Special Report is also available on the Internet as part of the FAO World Wide Web (www.fao.org) at the following URL address: http://www.fao.org/giews/ The Special Alerts/Reports can also be received automatically by E-mail as soon as they are published, by subscribing to the GIEWS/Alerts report ListServ. To do so, please send an E-mail to the FAO-Mail-Server at the following address: [email protected], leaving the subject blank, with the following message: subscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L To be deleted from the list, send the message: unsubscribe GIEWSAlertsWorld-L Please note that it is now possible to subscribe to regional lists to only receive Special Reports/Alerts by region: Africa, Asia, Europe or Latin America (GIEWSAlertsAfrica-L, GIEWSAlertsAsia-L, GIEWSAlertsEurope-L and GIEWSAlertsLA-L). These lists can be subscribed to in the same way as the worldwide list. -

Research Article

z Available online at http://www.journalcra.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CURRENT RESEARCH International Journal of Current Research Vol. 7, Issue, 03, pp.13512-13519, March, 2015 ISSN: 0975-833X RESEARCH ARTICLE DETERMINANTS OF MARKET PARTICIPATION DECISION AND LEVEL OF PARTICIPATION OF DAIRY FARMERS IN TIGRAY, ETHIOPIA: THE CASE OF RAYA *Kebede Abrha Mengstu, Hassen Mehammedbrehan Kahsay, Gebrekiros Hagos Belay and Abebe Tilahun Kassaye Department of Marketing, Mekelle University, Adi-haki Campus, Ethiopia ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: The study was undertaken with the objective of assessing determinants of dairy market participation Received 30th December, 2014 and level of participation in terms of litres of milk in Tigray, Ethiopia.240 households were selected Received in revised form using simple random sampling method. Data were collected using formal survey. The data collected 13th January, 2015 were analysed using both descriptive and Heckman two-step selection econometric models. The Accepted 03rd February, 2015 binary probit model results revealed that Age of the Household head, child age under six years old, Published online 17th March, 2015 family size, distance to the nearest market centre, transportation access and total litres produced per- day played a significant role in dairy market participation. Heckman second-step selection estimation Key words: indicated that level of education of the household head, access to extension services, Total litres Determinants, produced per day, land ownership and non dairy participation significantly affected level of dairy Heckman two-step model, market participation in litre of milk sales. The researchers recommend that government with its Participation, extension workers and other development institutions and partners should give due emphasis on Binary probit model, capacity building, which increases dairy households bargaining power by getting information related Level of participation in litres of milk sales. -

World Bank Document

PA)Q"bP Q9d9T rlPhGllPC LT.CIILh THE FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA Ph,$F&,P f1~77Pq ).rlnPQnlI (*) ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY w Port Otflce Box 1770 Addlr Ababa Ethlopla ra* ~3 ~TC1770 nRn nnrl rtms Cable Addreu Hlghways Addlr Ababa P.BL'ICP ill~~1ill,& aa~t+mn nnrl Public Disclosure Authorized Telex 21issO Tel. No. 551-71-70/79 t&hl 211860 PlOh *'PC 551-71-70179 4hb 251-11-5514865 Fax 251-11-551 866 %'PC Ref. No. MI 123 9 A 3 - By- " - Ato Negede Lewi Senior Transport Specialist World Bank Country Office Addis Ababa Ethiopia Public Disclosure Authorized Subject: APL 111 - Submission of ElA Reports Dear Ato Negede, As per the provisions of the timeframe set for the pre - appraisal and appraisal of the APL Ill Projects, namely: Public Disclosure Authorized 1. Aposto - Wendo - Negelle, 2. Gedo - Nekemte, 3. Gondar - Debark, and 4. Yalo - Dallol, we are hereby submitting, in both hard and soft copies, the final EIA Reports of the Projects, for your information and consumption, addressing / incorporating the comments received at different stages from the Bank. Public Disclosure Authorized SincP ly, zAhWOLDE GEBRIEl, @' Elh ,pion Roods Authority LJirecror General FEDERAL DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA ETHIOPIAN ROADS AUTHORITY E1546 v 4 N Y# Dalol W E Y# Kuneba Y# CONSULTANCYBerahile SERVICES S F OR FOR Ab-Ala Y# FEASIBILITY STUDY Y# ENVIRONMENTALAfdera IMPACT ASSESSMENT Megale Y# Y# Didigsala AND DETAILEDYalo ENGINEERING DESIGN Y# Y# Manda Y# Sulula Y# Awra AND Y# Serdo Y# TENDEREwa DOCUMENT PREPARATIONY# Y# Y# Loqiya Hayu Deday