Satellite Television in Indonesia*^

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at July 13, 2020 8:00 AM

City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM Call to Order Prayer Roll Call Opening Comments - Mayor Part I – Foundational review, Revenues & Budget Summary (Doug Racine) • Foundational Budget Discussion • Fiscal 2021 Budget Summary • Overall Budget Risks and Opportunities • Fund Budgets – Summarized review • General Government Summarized Budget Break Action Item: Council Discussion & Vote on FY2021 Budgets: Part II – Departmental Budgets, Capital Budgets, Grants & Position Control (Ed Karass) • Budget Development introduction (1) Departmental Budget Reviews 1-1. Clerks 1-2. Code Enforcement 1-3. Econ Development 1-4. Facilities 1-5. Finance 1-6. Legal 1-7. Workforce Development 1-8. IT 1-9. Mayor & City Council 1-10. General Government Lunch Break (1) Continued Review of Departmental Budget Reviews 1-11. Public Work Admin 1-12. Public Works Engineering 1-13. Fire 1-14. Police Page 1 of 3 City of Nampa Special City Council Meeting Budget Workshop Livestreaming at https://livestream.com/cityofnampa July 13, 2020 8:00 AM (2) Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-0. 911 2-1. Civic Center/Ford Idaho Center 2-2. Family Justice Center 2-3. Library 2-4. Parks & Recs (Incl Golf) 2-5. Stormwater 2-6. Streets / Airport 2-6. Water / Irrigation 2-7. Wastewater 2-8. Environmental Compliance 2-9. Sanitation / Utility Billing Break (2) Continued Review of Special Revenue, Enterprise & Internal Service Funds 2-10. Building / Development Services 2-11. Planning & Zoning 2-12. Fleet (4) Grants (5) Impact Fees (6) Capital Budget Review 6-0. -

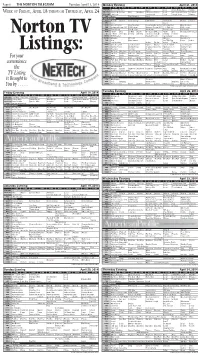

06 4-15-14 TV Guide.Indd

Page 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2014 Monday Evening April 21, 2014 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With Stars Castle Local Jimmy Kimmel Live Nightline WEEK OF FRIDAY, APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY, APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS 2 Broke G Friends Mike Big Bang NCIS: Los Angeles Local Late Show Letterman Ferguson KSNK/NBC The Voice The Blacklist Local Tonight Show Meyers FOX Bones The Following Local Cable Channels A&E Duck D. Duck D. Duck Dynasty Bates Motel Bates Motel Duck D. Duck D. AMC Jaws Jaws 2 ANIM River Monsters River Monsters Rocky Bounty Hunters River Monsters River Monsters CNN Anderson Cooper 360 CNN Tonight Anderson Cooper 360 E. B. OutFront CNN Tonight DISC Fast N' Loud Fast N' Loud Car Hoards Fast N' Loud Car Hoards DISN I Didn't Dog Liv-Mad. Austin Good Luck Win, Lose Austin Dog Good Luck Good Luck E! E! News The Fabul Chrisley Chrisley Secret Societies Of Chelsea E! News Norton TV ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Olbermann ESPN2 NFL Live 30 for 30 NFL Live SportsCenter FAM Hop Who Framed The 700 Club Prince Prince FX Step Brothers Archer Archer Archer Tomcats HGTV Love It or List It Love It or List It Hunters Hunters Love It or List It Love It or List It HIST Swamp People Swamp People Down East Dickering America's Book Swamp People LIFE Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Hoarders Listings: MTV Girl Code Girl Code 16 and Pregnant 16 and Pregnant House of Food 16 and Pregnant NICK Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Full H'se Friends Friends Friends SCI Metal Metal Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Warehouse 13 Metal Metal For your SPIKE Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Cops Jail Jail TBS Fam. -

Eko Murdiyanto ISBN

Perpustakaan Nasional : Katalog Dalam Terbitan (KDT) Eko Murdiyanto Sosiologi Perdesaan/ Eko Murdiyanto -Edisi I – Yogyakarta: UPN “Veteran” Yogyakarta 2008. 264 hlm: 21 cm ISBN: 978-979-8918-88-9 Hak cipta dilindungi oleh undang-undang Diterbitkan oleh: Wimaya Press UPN ”Veteran” Yogyakarta Edisi pertama : Desember 2008 Alamat Penerbit: Badan Usaha Universitas (BUU) Jl SWK 104 (Lingkar Utara), Condongcatur Yogyakarta. 55283 Telp/Fac: (0274) 489027 ISBN : 978-979-8918-88-9 ajian sosiologi perdesaan yang berfokus pada memahami memahami karakter masyarakat sebagai suatu komunitas Sosiologi Perdesaan Eko Murdiyanto Yang utuh semakin pesat perkembangannya. Hal ini seiring dengan kondisi masyarakat di perdesaan yang senantiasa berubah sejak revolusi industri bergulir di Eropa dan membawa konsekuensi perubahan dalam masyarakat yang cenderung cepat. Perubahan ini mendorong munculnya mobilitas penduduk di seluruh dunia. Sejalan dengan itu perubahan pola dalam mobilitas penduduk membawa implikasi bagi perkembangan masyarakat secara luas. Akibat yang kemudian muncul bagi daerah perdesaan, adalah perubahan baik secara fisik maupun sosial kemasyarakatan. Oleh karena itu proses mobilitas penduduk SOSIOLOGI atau migrasi harus senantiasa dipandang sebagai proses alami, sehingga perubahan dalam masyarakat yang ditimbulkannya dapat diantisipasi. Dengan memahami perubahan dalam masyarakat di perdesaan diharapkan program pengembangan masyarakat menuju masyarakat yang PERDESAAN lebih baik dapat dilakukan dengan smart. Buku ini mencoba memberikan wacana bagaimana memahami karakter masyarakat di perdesaan sebagai Pengantar Untuk Memahami suatu komunitas secara utuh, yaitu suatu pemahaman yang berasal dari dalam diri masyarakat itu sendiri. Hal ini diperlukan untuk memahami Masyarakat Desa kondisi masyarakat di perdesaan dalam rangka pengembangan masyarakat menuju masyarakat yang lebih baik dengan tidak meninggalkan masa lalu dan mengabaikan masa depan. -

Bab 2 Industri Dan Regulasi Penyiaran Di Indonesia

BAB 2 INDUSTRI DAN REGULASI PENYIARAN DI INDONESIA 2.1. Lembaga Penyiaran di Indonesia Dalam kehidupan sehari-hari, istilah lembaga penyiaran seringkali dianggap sama artinya dengan istilah stasiun penyiaran. Menurut Peraturan Menkominfo No 43 Tahun 2009, yang ditetapkan 19 Oktober 2009, lembaga penyiaran adalah penyelenggara penyiaran, baik Lembaga Penyiaran Publik, Lembaga Penyiaran Swasta, Lembaga Penyiaran Komunitas, maupun Lembaga Penyiaran Berlangganan yang dalam melaksanakan tugas, fungsi dan tanggungjawabnya berpedoman pada peraturan perundangan yang berlaku. Jika ditafsirkan, lembaga penyiaran adalah salah satu elemen dalam dunia atau sistem penyiaran. Dengan demikian walau lembaga penyiaran bisa dilihat sebagai segala kegiatan yang berhubungan dengan pemancarluasan siaran saja, namun secara implisit ia merupakan keseluruhan yang utuh dari lembaga-lembaga penyiaran (sebagai lembaga yang memiliki para pendiri, tujuan pendiriannya/visi dan misi, pengelola, perlengkapan fisik), dengan kegiatan operasional dalam menjalankan tujuan-tujuan penyiaran, serta tatanan nilai, dan peraturan dengan perangkat-perangkat regulatornya. Sedangkan stasiun penyiaran adalah tempat di mana program acara diproduksi/diolah untuk dipancarluaskan melalui sarana pemancaran dan/atau sarana transmisi di darat, laut atau antariksa dengan menggunakan spektrum frekuensi radio melalui udara, kabel, dan/atau media lainnya untuk dapat diterima secara serentak dan bersamaan oleh masyarakat dengan perangkat penerima siaran. Sedangkan penyiaran adalah kegiatan pemancarluasan -

06 4-15 TV Guide.Indd 1 4/15/08 7:49:32 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, April 15, 2008 Monday Evening April 21, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC Dancing With the Stars Samantha Bachelor-Lond Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live WEEK OF FRIDAY , APRIL 18 THROUGH THURSDAY , APRIL 24 KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Rules CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Medium Local Tonight Show Late FOX Bones House Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention I Survived Crime 360 Intervention AMC Ferris Bueller Teen Wolf StirCrazy ANIM Petfinder Animal Cops Houston Animal Precinct Petfinder Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Dirty Jobs Dirty Jobs Verminators How-Made How-Made Dirty Jobs DISN Finding Nemo So Raven Life With The Suite Montana Replace Kim E! Keep Up Keep Up True Hollywood Story Girls Girls E! News Chelsea Daily 10 Girls ESPN MLB Baseball Baseball Tonight SportsCenter Fastbreak Baseball Norton TV ESPN2 Arena Football Football E:60 NASCAR Now FAM Greek America's Prom Queen Funniest Home Videos The 700 Club America's Prom Queen FX American History X '70s Show The Riches One Hour Photo HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST Modern Marvels Underworld Ancient Discoveries Decoding the Past Modern Marvels LIFE Reba Reba Black and Blue Will Will The Big Match MTV True Life The Paper The Hills The Hills The Paper The Hills The Paper The Real World NICK SpongeBob Drake Home Imp. -

06 9/2 TV Guide.Indd 1 9/3/08 7:50:15 AM

PAGE 6 THE NORTON TELEGRAM Tuesday, September 2, 2008 Monday Evening September 8, 2008 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 KHGI/ABC H.S. Musical CMA Music Festival Local Nightline Jimmy Kimmel Live KBSH/CBS Big Bang How I Met Two Men Christine CSI: Miami Local Late Show-Letterman Late Late WEEK OF FRIDAY , SEPT . 5 THROUGH THUR S DAY , SEPT . 11 KSNK/NBC Deal or No Deal Toughest Jobs Dateline NBC Local Tonight Show Late FOX Sarah Connor Prison Break Local Cable Channels A&E Intervention Intervention After Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Paranorml Intervention AMC Alexander Geronimo: An American Legend ANIM Animal Cops Houston Animal Cops Houston Miami Animal Police Miami Animal Police Animal Cops Houston CNN CNN Election Center Larry King Live Anderson Cooper 360 Larry King Live DISC Mega-Excavators 9/11 Towers Into the Unknown How-Made How-Made Mega-Excavators DISN An Extremely Goofy Movie Wizards Wizards Life With The Suite Montana So Raven Cory E! Cutest Child Stars Dr. 90210 E! News Chelsea Chelsea Girls ESPN NFL Football NFL Football ESPN2 Poker Series of Poker Baseball Tonight SportsCenter NASCAR Now Norton TV FAM Secret-Teen Secret-Teen Secret-Teen The 700 Club Whose? Whose? FX 13 Going on 30 Little Black Book HGTV To Sell Curb Potential Potential House House Buy Me Sleep To Sell Curb HIST The Kennedy Assassin 9/11 Conspiracies The Kennedy Assassin LIFE Army Wives Tell Me No Lies Will Will Frasier Frasier MTV Exposed Exposed Exiled The Hills The Hills Exiled The Hills Exiled Busted Busted NICK Pets SpongeBob Fam. -

The Indonesia Policy on Television Broadcasting: a Politics and Economics Perspective

The Indonesia Policy on Television Broadcasting: A Politics and Economics Perspective Rendra Widyatamaab* and Habil Polereczki Zsoltb aDepartment of Communication, Ahmad Dahlan University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia b Károly Ihrig Doctoral School of Management And Business, University of Debrecen, Hungary *corresponding author Abstract: All around the world, the TV broadcasting business has had an enormous impact on the social, political and economic fields. Therefore, in general, most of the countries regulate TV business well to produce an optimal impact on the nation. In Indonesia, the TV broadcasting business is growing very significantly. After implementing Broadcasting Act number 32 of 2002, the number of TV broadcasting companies increased to 1,251 compared to before 2002, which only had 11 channels, and were dominated by the private TV stations. However, the economic contribution of the TV broadcasting business in Indonesia is still small. Even in 2017, the number of TV companies decreased by 14.23% to 1,073. This situation raises a serious question: how exactly does Indonesian government policy regulate the TV industry? This article is the result of qualitative research that uses interviews and document analysis as a method of collecting data. The results showed that the TV broadcasting industry in Indonesia can not develop properly because the government do not apply fair rules to the private TV industry. Political interests still color the formulation of rules in which the government and big TV broadcasting companies apply the symbiotic -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Benjamin F. Stickle Middle Tennessee State University Department of Criminal Justice Administration 1301 East Main Street - MTSU Box 238 Murfreesboro, Tennessee 37132 [email protected] www.benstickle.com (615) 898-2265 EDUCATION Doctor of Philosophy, 2015, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Master of Science, 2010, Justice Administration University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky Bachelor of Arts, 2005, Sociology Cedarville University, Cedarville, Ohio ACADEMIC POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2019 – Present Associate Professor 2016 – 2019 Assistant Professor Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2014 – 2016 Assistant Professor 2011 – 2014 Instructor (Full-time) University of Louisville, Department of Justice Administration 2014 – 2015 Lecturer ADMINISTRATIVE POSITIONS Middle Tennessee State University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Coordinator, Online Bachelor of Criminal Justice Administration 2018 – Present Chair, Curriculum Committee Campbellsville University, Department of Criminal Justice Administration 2011-2016 Site Coordinator, Louisville Education Center PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS & AFFILIATIONS 2019 – Present Affiliated Faculty, Political Economy Research Institute, Middle Tennessee State University 2017 – Present Senior Fellow for Criminal Justice, Beacon Center of Tennessee Ben Stickle CV, Page 2 AREAS OF SPECIALIZATION • Property Crime: Metal -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 136 2nd International Conference on Social and Political Development (ICOSOP 2017) The Power of the Screen: Releasing Oneself from the Influence of Capital Owners Puji Santoso Muhammadiyah Sumatera Utara University (UMSU) Email: [email protected] Abstract— Indonesia’s Media has long played a pivotal role in every changing. The world’s dependence on political, economic, and cultural changes leads the media playing an active role in the change order. It is not uncommon that the media has always been considered as an effective means to control changes or the process of social transformation. In the current era of reformation, the press, especially television industry has been experiencing rapid development. This is triggered by the opportunities opened for capital owners to invest their money into media business of television. Furthermore, the entrepreneurs or the capital owners capitalize the benefits by establishing several media subsidiaries. They try to seize the freely opened opportunity to create journalistic works. The law stipulates that press freedom is a form of popular sovereignty based on the principles of democracy, justice, and legal sovereignty. The mandate of this law indicates that press freedom should reflect people’s sovereignty. The sovereign people are the people in power and have the power to potentially develop their life-force as much as possible. At present, Indonesia has over 15 national television stations, 12 of which are networked televisions, and no less than 250 local television stations. This number is projected to be increasing based on data on the number of lined up permit applicants registered at the Ministry of Communications and Information office (Kemenkominfo) or at the Indonesian Broadcasting Commission (KPI) office both at the central and regional levels. -

International Journal of Multicultural and Multireligious Understanding Construction of Reality in Post-Disaster News on Televis

Comparative Study of Post-Marriage Nationality Of Women in Legal Systems of Different Countries http://ijmmu.com [email protected] International Journal of Multicultural ISSN 2364-5369 Volume 6, Issue 3 and Multireligious Understanding June, 2019 Pages: 845-853 Construction of Reality in Post-Disaster News on Television Programs: Analysis of Framing in "Sulteng Bangkit" News Program on TVRI Arif Pujo Suroko; Widodo Muktiyo; Andre Novie Rahmanto Department of Communication Science, Universitas Sebelas Maret, Indonesia , Universita http://dx.doi.org/10.18415/ijmmu.v6i3.876 Abstract Television is a mass media which has always been a top priority for the community in getting accurate and reliable information. The presence of television will always be awaited by the public to convey all information, especially when natural disasters occur in an area. This article tries to provide an analysis of the news program produced by the TVRI Public Broadcasting Institutions. This study uses the framing analysis method, with a four-dimensional structural approach to the news text as a framing device from Zhongdang Pan and Gerald M. Kosicki. This analysis aims to understand and then describe how reality is constructed by TVRI broadcasting institutions in the frame of television news programs on natural disasters, earthquakes and sunbaths in Central Sulawesi. The results of the analysis with framing showed that TVRI's reporting through the special program of natural disaster recovery "Sulteng Bangkit" showed prominence on the government's role in the process of handling and restoring conditions after the earthquake and tsunami natural disaster in Central Sulawesi. Keywords: Reality Construction; TV Programs; Media Framing; Natural Disasters 1. -

Senderliste-Digital-Tv.Pdf

Zusatz-Pakete Alle Preise pro Monat. Premium CHF 33.– Entertainment CHF 22.– Sports CHF 11.– 2 Monate1) gratis Im Premium-Paket erhalten Sie alles in einem: Plus, Entertainment, Sports und den Erotik-Sender Blue Hustler. 188 Nicktoons 271 Eurosport 1 HD 189 Cartoon Netw. HD d/e 272 Eurosport 2 HD 190 Boomerang HD d/e 274 sport1+ HD 194 Fix & Foxi 275 sportdigital HD CHF 5.– Plus 197 Nick Jr. 278 Auto Motor & Sport HD 201 Animal Planet HD 279 Motors TV HD d/f/e Deutschsprachige Sender Weitere Sprachen 202 Nat Geo Wild HD d/e 282 sport 1 US HD e 100 RTL HD 448 Extremadura SAT spa 203 Nat Geo HD d/e 285 Extreme Sports Channel d/f/e 101 SAT.1 HD 494 CT24 Czech News cze 204 Discovery HD 286 Fast&FunBox HD e 102 ProSieben HD 497 Duna TV HD hun PLANET 205 HD Planet HD 287 FightBox HD e 103 VOX HD 498 TVRi Romania Int. rum 206 GEO Television HD d/e 290 Nautical Channel HD e/f 104 RTL 2 HD 501 Slovenija 1 slv 212 Travel Channel HD d/e 105 kabel eins HD 508 Z1 TV Sljeme hrv 219 History HD d/e 107 RTLNITRO HD 509 DM Sat srp 221 A&E d/e 108 n-tv HD 521 RTRS plus bos Adult CHF 24.– 227 Bon Gusto HD 111 Super RTL HD 522 OBN bos 295 Penthouse HD 230 E! Entertainment HD d/e 113 sixx HD 529 RTCG TV Montenegro mon 296 Blue Hustler2) 232 RTL Living HD 124 Anixe HD Serie 536 TVSH Shqiptar alb 297 Hustler TV 233 RTL Passion HD 133 Welt der Wunder 551 TRT 1 HD tur 298 Private TV 236 Romance TV HD 163 Gute Laune TV 557 Kanal D (Euro D) tur 237 Universal Channel HD d/e Sender mit 7 Tage Replay-Funktion auf Verte! TV. -

Changes in Cultural Representations on Indonesian Children's Television from the 1980S to the 2000S

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Lirias Asian Journal of Communication ISSN: 0129-2986 (Print) 1742-0911 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rajc20 Changes in cultural representations on Indonesian children's television from the 1980s to the 2000s Hendriyani, Ed Hollander, Leen d'Haenens & Johannes W. J. Beentjes To cite this article: Hendriyani, Ed Hollander, Leen d'Haenens & Johannes W. J. Beentjes (2016): Changes in cultural representations on Indonesian children's television from the 1980s to the 2000s, Asian Journal of Communication, DOI: 10.1080/01292986.2016.1156718 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2016.1156718 Published online: 15 Mar 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 5 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rajc20 Download by: [78.22.197.120] Date: 18 March 2016, At: 14:19 ASIAN JOURNAL OF COMMUNICATION, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2016.1156718 Changes in cultural representations on Indonesian children’s television from the 1980s to the 2000s Hendriyania,b, Ed Hollanderc, Leen d’Haenensd and Johannes W. J. Beentjese aDepartment of Communication, Universitas Indonesia, Gedung Komunikasi lantai 2 FISIP, Depok, 16424 Jawa Barat, Indonesia; bRadboud University Nijmegen, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; cEmeritus Associate Professor at the Department of Communication, Radboud