Final Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ports Rail 3

68693 Public Disclosure Authorized Caucasus Transport Corridor for Oil and Oil Products Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by: ECSSD The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized December 2008 Abbreviations and Acronyms ACG Azeri, Chirag and deepwater Gunashli (oil fields) ADDY Azerbaijan Railway AIOC Azerbaijan International Oil Consortium bpd Barrels per day BTC Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (pipeline) CA or CAR Central Asian Region Caspar Azerbaijan State Caspian Shipping Company CIS Commonwealth of Independent States CNPC China National Petroleum Corporation CPC Caspian Pipeline Consortium (pipeline) dwt Deadweight ton FOB Free on board FSU Former Soviet Union GDP Gross Domestic Product GR Georgian Railway km Kilometer KCTS Kazakhstan Caspian Transport System KMG KazMunaiGaz KMTP Kazmortransflot kV Kilovolt MEP Middle East Petroleum MOU Memorandum of Understanding OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development RTC Rail tank-car RZD Russian Railway SOCAR State Oil Company of Azerbaijan tpa Tons per annum (per year), metric TRACECA Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia Vice President, Europe and Central Asia: Shigeo Katsu, ECAVP Country Director: Donna Dowsett-Coirolo, ECCU3 Sector Director: Peter D. Thomson, ECSSD Sector Manager, Transport: Motoo Konishi, ECSSD Task Team Leader: Martha Lawrence, ECSSD I II Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. CASPIAN OIL TRANSPORT MARKET DYNAMICS Outlook for Caspian Oil Production Transport Options for Caspian Oil 2. CAUCASUS RAIL CORRIDOR—PHYSICAL CONSTRAINTS Ports -

Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map

Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map The Asian Development Bank (ADB) is preparing sector assessments and road maps to help align future ADB support with the needs and strategies of developing member countries and other development partners. The transport sector assessment of Georgia is a working document that helps inform the development of country partnership strategy. It highlights the development issues, needs and strategic assistance priorities of the transport sector in Georgia. The knowledge product serves as a basis for further dialogue on how ADB and the government can work together to tackle the challenges of managing transport sector development in Georgia in the coming years. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.7 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 828 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. Georgia Transport Sector ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main Assessment, Strategy, instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. and Road Map TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS. Georgia. 2014 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed in the Philippines Georgia Transport Sector Assessment, Strategy, and Road Map © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION at the LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI and TBILISI © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung

YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION AT THE LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI AND TBILISI © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung This Publication is funded by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung. Commercial use of all media published by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) is not permitted without the written consent of the FES. YOUTH POLICY IMPLEMENTATION AT THE LOCAL LEVEL: IMERETI AND TBILISI Tbilisi 2020 Youth Policy Implementation at the Local Level: Imereti and Tbilisi Tbilisi 2020 PUBLISHERS Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, South Caucasus South Caucasus Regional Offi ce Ramishvili Str. Blind Alley 1, #1, 0179 http://www.fes-caucasus.org Tbilisi, Georgia Analysis and Consulting Team (ACT) 8, John (Malkhaz) Shalikashvili st. Tbilisi, 0131, Georgia Parliament of Georgia, Sports and Youth Issues Committee Shota Rustaveli Avenue #8 Tbilisi, Georgia, 0118 FOR PUBLISHER Felix Hett, FES, Salome Alania, FES AUTHORS Plora (Keso) Esebua (ACT) Sopho Chachanidze (ACT) Giorgi Rukhadze (ACT) Sophio Potskhverashvili (ACT) DESIGN LTD PolyGraph, www.poly .ge TYPESETTING Gela Babakishvili TRANSLATION & PROOFREADING Lika Lomidze Eter Maghradze Suzanne Graham COVER PICTURE https://www.freepik.com/ PRINT LTD PolyGraph PRINT RUN 150 pcs ISBN 978-9941-8-2018-2 Attitudes, opinions and conclusions expressed in this publication- not necessarily express attitudes of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung does not vouch for the accuracy of the data stated in this publication. © Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung 2020 FOREWORD Youth is important. Many hopes are attached to the “next generation” – societies tend to look towards the young to bring about a value change, to get rid of old habits, and to lead any country into a better future. -

Economic Prosperity Initiative

USAID/GEORGIA DO2: Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth October 1, 2011 – September 31, 2012 Gagra Municipal (regional) Infrastructure Development (MID) ABKHAZIA # Municipality Region Project Title Gudauta Rehabilitation of Roads 1 Mtskheta 3.852 km; 11 streets : Mtskheta- : Mtanee Rehabilitation of Roads SOKHUMI : : 1$Mestia : 2 Dushet 2.240 km; 7 streets :: : ::: Rehabilitation of Pushkin Gulripshi : 3 Gori street 0.92 km : Chazhashi B l a c k S e a :%, Rehabilitaion of Gorijvari : 4 Gori Shida Kartli road 1.45 km : Lentekhi Rehabilitation of Nationwide Projects: Ochamchire SAMEGRELO- 5 Kareli Sagholasheni-Dvani 12 km : Highway - DCA Basisbank ZEMO SVANETI RACHA-LECHKHUMI rehabilitaiosn Roads in Oni Etseri - DCA Bank Republic Lia*#*# 6 Oni 2.452 km, 5 streets *#Sachino : KVEMO SVANETI Stepantsminda - DCA Alliance Group 1$ Gali *#Mukhuri Tsageri Shatili %, Racha- *#1$ Tsalenjikha Abari Rehabilitation of Headwork Khvanchkara #0#0 Lechkhumi - DCA Crystal Obuji*#*# *#Khabume # 7 Oni of Drinking Water on Oni for Nakipu 0 Likheti 3 400 individuals - Black Sea Regional Transmission ZUGDIDI1$ *# Chkhorotsku1$*# ]^!( Oni Planning Project (Phase 2) Chitatskaro 1$!( Letsurtsume Bareuli #0 - Georgia Education Management Project (EMP) Akhalkhibula AMBROLAURI %,Tsaishi ]^!( *#Lesichine Martvili - Georgia Primary Education Project (G-Pried) MTSKHETA- Khamiskuri%, Kheta Shua*#Zana 1$ - GNEWRC Partnership Program %, Khorshi Perevi SOUTH MTIANETI Khobi *# *#Eki Khoni Tskaltubo Khresili Tkibuli#0 #0 - HICD Plus #0 ]^1$ OSSETIA 1$ 1$!( Menji *#Dzveli -

6. Imereti – Historical-Cultural Overview

SFG2110 SECOND REGIONAL DEVELOPMETN PROJECT IMERETI REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM IMERETI TOURISM DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Public Disclosure Authorized STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL, CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Tbilisi, December, 2014 ABBREVIATIONS GNTA Georgia National Tourism Administration EIA Environnemental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EMS Environmental Management System IFI International Financial Institution IRDS Imereti Regional Development Strategy ITDS Imereti Tourism Development Strategy MDF Municipal Development Fund of Georgia MoA Ministry of Agriculture MoENRP Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources Protection of Georgia MoIA Ministry of Internal Affairs MoCMP Ministry of Culture and Monument Protection MoJ Ministry of Justice MoESD Ministry of Economic and Sustaineble Developmnet NACHP National Agency for Cultural Heritage Protection PIU Project Implementation Unit PPE Personal protective equipment RDP Regional Development Project SECHSA Strategic Environmental, Cultural Heritage and Social Assessment WB World Bank Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................... 0 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 PROJECT CONTEXT ............................................................................................................................... -

Pilot Integrated Regional Development Programme for Guria, Imereti, Kakheti and Racha Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti 2020-2022 2019

Pilot Integrated Regional Development Programme for Guria, Imereti, Kakheti and Racha Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti 2020-2022 2019 1 Table of Contents List of maps and figures......................................................................................................................3 List of tables ......................................................................................................................................3 List of Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................4 Chapter I. Introduction – background and justification. Geographical Coverage of the Programme .....6 1.1. General background ........................................................................................................................... 6 1.2. Selection of the regions ..................................................................................................................... 8 Chapter II. Socio-economic situation and development trends in the targeted regions .........................9 Chapter ...........................................................................................................................................24 III. Summary of territorial development needs and potentials to be addressed in targeted regions .... 24 Chapter IV. Objectives and priorities of the Programme ................................................................... 27 4.1. Programming context for setting up PIRDP’s objectives and priorities .......................................... -

2018 Presidential Election First Interim Report of the Pre-Election Monitoring

2018 Presidential Election First Interim Report of the Pre-Election Monitoring (August 1 - September 8) 13 September 2018 This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). Views expressed in this publication belong solely to the International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, the United States Government or the NED. Table of Contents I. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 2 II. Key Findings ........................................................................................................................................ 2 III. Recommendations ......................................................................................................................... 4 IV. Electoral Administration ............................................................................................................. 5 Appointment of Temporary Members of DECs ................................................................................. 5 V. Media environment ........................................................................................................................ 9 VI. Intimidation/harassment on alleged political grounds ...................................................... 12 VII. Physical confrontation .............................................................................................................. -

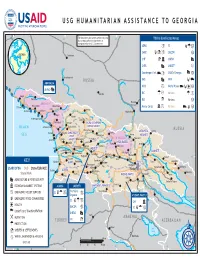

Georgia Program Maps 10/31/2008

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO GEORGIA 40° E 42° E The boundaries and names used on this map 44° E T'bilisi & Affected46° E Areas Majkop do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. Government. ADRA a SC Ga I GEORGIA CARE a UMCOR a Cherkessk CHF IC UNFAO CaspianA Sea 44° CNFA A UNICEF J N 44° Kuban' Counterpart Int. Ea USAID/Georgia Aa N Karachayevsk RUSSIA FAO A WFP E ABKHAZIA E !0 Psou IOCC a World Vision Da !0 UNFAO A 0 Nal'chik IRC G J Various G a ! Gagra Bzyb' Groznyy RUSSIA 0 Pskhu IRD I Various a ! Nazran "ABKHAZIA" Novvy Afon Pitsunda 0 Omarishara Mercy Corps Ca Various E a ! Lata Sukhumi Mestia Gudauta!0 !0 Kodori Inguri Vladikavkaz Otap !0 Khaishi Kvemo-gulripsh Lentekhi !0 Tkvarcheli Dzhvari RACHA-LECHKHUMI-RACHA-LECHKHUMI- Terek BLACK Ochamchira Gali Tsalenjhikha KVEMOKVEMO SVANETISVANETI RUSSIA Khvanchkara Rioni MTSKHETA-MTSKHETA- Achilo Pichori Zugdidi SAMEGRELO-SAMEGRELO- Kvaisi Mleta SEA ZEMOZEMO Ambrolauri MTIANETIMTIANETI Pasanauri Alazani Khobi Tskhaltubo Tkibuli "SOUTH OSSETIA" Anaklia SVANETISVANETI Aragvi Qvirila SHIDASHIDA KARTLIKARTLI Senaki Kurta Artani Rioni Samtredia Kutaisi Chiatura Tskhinvali Poti IMERETIIMERETI Lanchkhuti Rioni !0 Akhalgori KAKHETIKAKHETI Chokhatauri Zestafoni Khashuri N Supsa Baghdati Dusheti N 42° Kareli Akhmeta Kvareli 42° Ozurgeti Gori Kaspi Borzhomi Lagodekhi KEY Kobuleti GURIAGURIA Bakhmaro Borjomi TBILISITBILISI Telavi Abastumani Mtskheta Gurdzhaani Belokany USAID/OFDA DoD State/EUR/ACE Atskuri T'bilisi Î! Batumi 0 AJARIAAJARIA Iori ! Vale Akhaltsikhe Zakataly State/PRM -

Realizing the Urban Potential in Georgia: National Urban Assessment

REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA National Urban Assessment ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK REALIZING THE URBAN POTENTIAL IN GEORGIA NATIONAL URBAN ASSESSMENT ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2016 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. Published in 2016. Printed in the Philippines. ISBN 978-92-9257-352-2 (Print), 978-92-9257-353-9 (e-ISBN) Publication Stock No. RPT168254 Cataloging-In-Publication Data Asian Development Bank. Realizing the urban potential in Georgia—National urban assessment. Mandaluyong City, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 2016. 1. Urban development.2. Georgia.3. National urban assessment, strategy, and road maps. I. Asian Development Bank. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) or its Board of Governors or the governments they represent. ADB does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication and accepts no responsibility for any consequence of their use. This publication was finalized in November 2015 and statistical data used was from the National Statistics Office of Georgia as available at the time on http://www.geostat.ge The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by ADB in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. By making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area, or by using the term “country” in this document, ADB does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Multifunctional Transshipment Terminal at Port of Poti, Georgia Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment

TRANSFORD LLC Multifunctional Transshipment Terminal at Port of Poti, Georgia Updated Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Tbilisi 2015 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 2 Updated ESIA ............................................................................................................... 8 3 Environmental and Social Objectives of the Report ..................................................... 10 4 Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Methodology ....................................... 10 5 Legal and Regulatory Framework ................................................................................ 11 5.1 Georgian legislation .............................................................................................. 11 5.2 Environmental Standards in Georgia .................................................................... 15 5.3 Environmental Impact Assessment in Georgia ..................................................... 17 5.4 IFC Performance Standards ................................................................................. 18 5.5 International Conventions ..................................................................................... 19 5.6 Marine sediment quality guidelines ....................................................................... 20 5.7 Gaps between Georgian legislation and IFC requirements ................................... 21 6 Project Description ..................................................................................................... -

Investment Opportunities in Manufacturing of Apparel Footwear

INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES IN MANUFACTURING OF APPAREL, FOOTWEAR AND BAGS IN GEORGIA 2019 GEORGIA COUNTRY OVERVIEW Area: 69,700 sq. km Population: 3.7 mln GDP 2018: USD 16.2 billions Life expectancy at GDP real growth rate 2018: 4.7 % birth 2018: 74 years GDP CAGR 2013-2018 (GEL): Georgian 4 % GDP per capita 2018: Literacy: 99.8 % USD 4346 Inflation rate (December) 2018 (Y-o-Y): 1.5% Capital: Tbilisi Total Public Debt to Nominal GDP (%) 2018: 42.2% Currency (code): Lari (GEL) INVESTMENT CLIMATE & 2 OPPORTUNITIES IN GEORGIA OVERVIEW OF MANUFACTURING SECTOR Georgia has a rich history of Contract manufacturing of apparel Footwear and bags manufacturing manufacturing apparel, textile is well developed in Georgia and sector has emerged recently and and footwear, dating back to existing factories produce apparel local manufacturers have started to Soviet times for famous international brands, export their products to different such as Moncler, Tommy Hilfiger, international markets Nike, Adidas, Mexx, Zara, Puma, Autograph, Lebek, Hawes & Curtis, M&S, HM, etc. In addition, leather production is also developing in Georgia and Georgian leather is already being exported to Italy and Turkey RUSSIA Zugdidi Anaklia BLACK Poti SEA Samtredia Batumi Ozurgeti Existing clusters Thriving locations TURKEY Main Roads ARMENIA AZERBAIJAN APPAREL BRANDS CURRENTLY PRODUCED IN GEORGIA Source: Geostat; KPMG Note: *-preliminary data INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 3 OF MANUFACTURING FOOTWEAR AND BAGS IN GEORGIA LIBERAL TRADE REGIMES Very simple and service oriented customs -

ANALYSIS of EMPLOYMENT and UNEMPLOYMENT in MUNICIPALITIES of GEORGIA (Target Municipalities: Lentekhi, Oni, Ambrolauri, Tskaltubo, Samtredia, Tsageri)77

European Scientific Journal December 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition Vol.2 ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 ANALYSIS OF EMPLOYMENT AND UNEMPLOYMENT IN MUNICIPALITIES OF GEORGIA (Target municipalities: Lentekhi, Oni, Ambrolauri, Tskaltubo, Samtredia, Tsageri)77 Murtaz Kvirkvaia, Professor Grigol Robakidze University, Tbilisi, Georgia Abstract The article includes detailed employment and uniploymant analysis in each municipality. In the analysis we use results from household survey conducted by the National Statistics Service. More specific information about the labour market at the municipal level was collected through cooperation with local municipalities. For the analysis we used information from municipalities’ web pages, telephone conversations with stakeholders, personal meetings with experts and so on. It should also be noted that a certain part of the data obtained from municipalities and from administrative territorial units have an approximate nature, but based on these information it is possible to gain some valuable conclusions and make assumptions. Terms and reality of employment analysis is carried out not only at the level of the municipality but on the country and regional ones as well. Keywords: Labor market; Unemployment; Employment analysis; local municipalities; Economically Active population; Self-employed; Integrated household survey Introduction The target municipalities (Lentekhi, Oni, Ambrolauri, Tskaltubo, Samtredia, Tsageri) are located in specific regions of Georgia. For example, a municipality of Samtredia and Tskaltubo are in Imereti region, and the other four target municipalities are in Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti region. For the evaluation of the general situation we consider the labor statistics on the country and regional level. Originally a brief analysis of the 77 This analysis was done under the UNDP/AF project.