The Catholic Lobby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (Bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167

David Goldstein and Martha Moore Avery Papers 1870-1958 (bulk 1917-1940) MS.1986.167 http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4438 Archives and Manuscripts Department John J. Burns Library Boston College 140 Commonwealth Avenue Chestnut Hill 02467 library.bc.edu/burns/contact URL: http://www.bc.edu/burns Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Biographical note: David Goldstein .............................................................................................................. 6 Biographical note: Martha Moore Avery ...................................................................................................... 7 Scope and Contents ........................................................................................................................................ 9 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Collection Inventory ..................................................................................................................................... 11 I: David Goldstein -

Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Monday, August

Saint John Gualbert Cathedral PO Box 807 Johnstown PA 15907-0807 539-2611 Stay awake and be ready! 536-0117 For you do not know on what day your Lord will come. Cemetery Office 536-0117 Fax 535-6771 Sunday, August 11, - Nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Readings: Wisdom 18:6-9/ Hebrews 11:1-2, 8-19 or 11:1-2, 8-12/ Luke 12:32-48 or 12:35-40 [email protected] 8:00 am: For the Intentions of the People of the Parish 11:00 am: Clarence Michael O’Shea (Great Granddaughter Dianne O’Shea) Bishop 5:00 pm: John Concannon (Kevin Klug) Most Rev Mark L Bartchak, DD Monday, August 12, - Weekday, Saint Jane Frances de Chantal, Religious Rector & Pastor Readings: Deuteronomy 10:12-22/ Matthew 17:22-27 Very Rev James F Crookston 7:00 am: Saint Anne Society 12:05 pm: Sophie Wegrzyn, Birthday Remembrance (Son, John) Parochial Vicar Father Clarence S Bridges Tuesday, August 13, - Weekday, Saints Pontian, Pope, & Hippolytus, Priest, Martyrs Readings: Deuteronomy 31:1-8/ Matthew 18:1-5, 10, 12-14 In Residence 7:00 am: Living & Deceased Members of 1st Catholic Slovac Ladies Father Sean K Code 12:05 pm: Bishop Joseph Adamec (Deacon John Concannon, Monica & Angela Kendera) SUNDAY LITURGY Wednesday, Saint Maximilian Kolbe, Priest & Martyr Saturday Evening Readings: Deuteronomy 34:1-12/ Matthew 18:15-20 5:00 pm Vigil Readings: 1 Chronicles 15:3-4, 15-16; 16:1-2/ 1 Corinthians 15:54b-57/ Luke 11:27-28 Sundays 7:00 am: Carole Vogel (Helen Muha) 8:00 am 12:05 pm: Anna Mae Cicon (Daughter, Melanie) 11:00 am 6:00 pm: Sara (Connors) O’Shea (Great Granddaughter, Dianne O’Shea 5:00 pm Thursday, August 15, - The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary Readings: Revelation 11:19a; 12:1-6a, 10ab/ Corinthians 15:20-27/ Luke 1:39-50 7:00 am: Robert F. -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

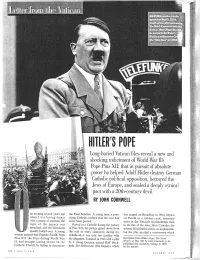

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Katholisches Wort in Die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014

Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem katholischen Glauben treu!“ 68 Gerhard Stumpf: Reformer und Wegbereiter in der Kirche: Klemens Maria Hofbauer 76 Franz Salzmacher: Europa am Scheideweg 82 Katholisches Wort in die Zeit 45. Jahr März 2014 DER FELS 3/2014 65 Formen von Sexualität gleich- Liebe Leser, wertig sind. Eine Vorgeschichte hat weiterhin die Insolvenz des kircheneigenen Unternehmens der Karneval ist in der katho- „Weltbild“. Das wirtschaftliche lischen Welt zuhause, wo sich Desaster ist darauf zurückzufüh- der Rhythmus des Lebens auch ren, dass die Geschäftsführung im Kirchenjahr widerspiegelt. zu spät auf das digitale Geschäft Die Kirche kennt eben die Natur gesetzt hat. Hinzu kommt die INHALT des Menschen und weiß, dass er Sortimentsausrichtung, die mit auch Freude am Leben braucht. Esoterik, Pornographie und sa- tanistischer Literatur, trotz vie- Papst Franziskus: Lebensfreude ist nicht gera- Das Licht Christi in tiefster Finsternis ....67 de ein Zeichen, das unsere Zeit ler Hinweise über Jahrzehnte, charakterisiert. Die zunehmen- keineswegs den Anforderungen Prof. Dr. Konrad Löw: : den psychischen Erkrankungen eines kircheneigenen Medien- Pius XII.: „Bleibt dem sprechen jedenfalls nicht dafür. unternehmens entsprach. Eine katholischen Glauben treu!“ .................68 „Schwermut ist die Signatur der Vorgeschichte hat schließlich die Gegenwart geworden“, lautet geistige Ausrichtung des ZDK Raymund Fobes: der Titel eines Artikels, der die- und der sie tragenden Großver- Seid das Salz der Erde ........................72 ser Frage nachgeht (Tagespost, bände wie BDKJ, katholische 1.2.14). Frauenverbände etc. Prälat Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Lothar Roos: Die Menschen erleben heute, Die selbsternannten „Refor- „Ein Licht für das Leben mer“ der deutschen Ortskirche in der Gesellschaft“ (Lumen fidei) .........74 dass sie mit verdrängten Prob- lemen immer mehr in Tuchfüh- ereifern sich immer wieder ge- Gerhard Stumpf: lung kommen. -

Angels Bible

ANGELS All About the Angels by Fr. Paul O’Sullivan, O.P. (E.D.M.) Angels and Devils by Joan Carroll Cruz Beyond Space, A Book About the Angels by Fr. Pascal P. Parente Opus Sanctorum Angelorum by Fr. Robert J. Fox St. Michael and the Angels by TAN books The Angels translated by Rev. Bede Dahmus What You Should Know About Angels by Charlene Altemose, MSC BIBLE A Catholic Guide to the Bible by Fr. Oscar Lukefahr A Catechism for Adults by William J. Cogan A Treasury of Bible Pictures edited by Masom & Alexander A New Catholic Commentary on Holy Scripture edited by Fuller, Johnston & Kearns American Catholic Biblical Scholarship by Gerald P. Fogorty, S.J. Background to the Bible by Richard T.A. Murphy Bible Dictionary by James P. Boyd Christ in the Psalms by Patrick Henry Reardon Collegeville Bible Commentary Exodus by John F. Craghan Leviticus by Wayne A. Turner Numbers by Helen Kenik Mainelli Deuteronomy by Leslie J. Hoppe, OFM Joshua, Judges by John A. Grindel, CM First Samuel, Second Samuel by Paula T. Bowes First Kings, Second Kings by Alice L. Laffey, RSM First Chronicles, Second Chronicles by Alice L. Laffey, RSM Ezra, Nehemiah by Rita J. Burns First Maccabees, Second Maccabees by Alphonsel P. Spilley, CPPS Holy Bible, St. Joseph Textbook Edition Isaiah by John J. Collins Introduction to Wisdom, Literature, Proverbs by Laurance E. Bradle Job by Michael D. Guinan, OFM Psalms 1-72 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Psalms 73-150 by Richard J. Clifford, SJ Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther by James A. -

Chapter 18: Roosevelt and the New Deal, 1933-1939

Roosevelt and the New Deal 1933–1939 Why It Matters Unlike Herbert Hoover, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was willing to employ deficit spending and greater federal regulation to revive the depressed economy. In response to his requests, Congress passed a host of new programs. Millions of people received relief to alleviate their suffering, but the New Deal did not really end the Depression. It did, however, permanently expand the federal government’s role in providing basic security for citizens. The Impact Today Certain New Deal legislation still carries great importance in American social policy. • The Social Security Act still provides retirement benefits, aid to needy groups, and unemployment and disability insurance. • The National Labor Relations Act still protects the right of workers to unionize. • Safeguards were instituted to help prevent another devastating stock market crash. • The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation still protects bank deposits. The American Republic Since 1877 Video The Chapter 18 video, “Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal,” describes the personal and political challenges Franklin Roosevelt faced as president. 1928 1931 • Franklin Delano • The Empire State Building 1933 Roosevelt elected opens for business • Gold standard abandoned governor of New York • Federal Emergency Relief 1929 Act and Agricultural • Great Depression begins Adjustment Act passed ▲ ▲ Hoover F. Roosevelt ▲ 1929–1933 ▲ 1933–1945 1928 1931 1934 ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ 1930 1931 • Germany’s Nazi Party wins • German unemployment 1933 1928 107 seats in Reichstag reaches 5.6 million • Adolf Hitler appointed • Alexander Fleming German chancellor • Surrealist artist Salvador discovers penicillin Dali paints Persistence • Japan withdraws from of Memory League of Nations 550 In this Ben Shahn mural detail, New Deal planners (at right) design the town of Jersey Homesteads as a home for impoverished immigrants. -

EXTENSIONS of REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

10672 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS May 8, 1980 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL SECURITY LEAKS potentiaf sources of intelligence infor Some of the stories say this informa mation abroad are reluctant to deal tion is coming out after all of the with our intelligence services for fear people involved have fled to safety. HON. LES ASPIN that their ties Will be exposed on the Maybe and maybe not. But if we are OF WISCONSIN front pages of American newspapers, worried about the cooperatic1n of for IN THE -HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES either because of leaks from Congress eigners, leaks like these would make Thursday, May 8, ,1980 or because sensitive material has been them extremely nervous about cooper leveraged out of the administration by ation. How can the leaker or leakers e Mr. ASPIN. Mr. Speaker, it is time FOIA. know everyone is safe? that we in Congress complain -}ust as We are also being told that, because Mr. Speaker, if foreigners are reluc loudly as those in the administration foreigners are fearful that secrets will tant to cooperate with us, it is the about national security leaks. be leaked, the intelligence agencies fault of our own agencies. Administrations, be they Republican must have the power to blue pencil They should know that the fault is or Democrat, have a predilection for manuscripts written by present and not. in Congress or in the FOIA but in pointing at Congress and bewailing former intelligence officers to make themselves. Recall that despite weeks the fact that the legislative branch sure they don't reveal anything sensi of forewarning, our people rushed out can't keep a secret. -

American Catholicism and the Political Origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1991 American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/ Thomas M. Moriarty University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Moriarty, Thomas M., "American Catholicism and the political origins of the Cold War/" (1991). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 1812. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/1812 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORI ARTY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 1991 Department of History AMERICAN CATHOLICISM AND THE POLITICAL ORIGINS OF THE COLD WAR A Thesis Presented by THOMAS M. MORIARTY Approved as to style and content by Loren Baritz, Chair Milton Cantor, Member Bruce Laurie, Member Robert Jones, Department Head Department of History TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. "SATAN AND LUCIFER 2. "HE HASN'T TALKED ABOUT ANYTHING BUT RELIGIOUS FREEDOM" 25 3. "MARX AMONG THE AZTECS" 37 4. A COMMUNIST IN WASHINGTON'S CHAIR 48 5. "...THE LOSS OF EVERY CATHOLIC VOTE..." 72 6. PAPA ANGEL I CUS 88 7. "NOW COMES THIS RUSSIAN DIVERSION" 102 8. "THE DEVIL IS A COMMUNIST" 112 9. -

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection BOOK NO

Kenneth A. Merique Genealogical and Historical Collection SUBJECT OR SUB-HEADING OF SOURCE OF BOOK NO. DATE TITLE OF DOCUMENT DOCUMENT DOCUMENT BG no date Merique Family Documents Prayer Cards, Poem by Christopher Merique Ken Merique Family BG 10-Jan-1981 Polish Genealogical Society sets Jan 17 program Genealogical Reflections Lark Lemanski Merique Polish Daily News BG 15-Jan-1981 Merique speaks on genealogy Jan 17 2pm Explorers Room Detroit Public Library Grosse Pointe News BG 12-Feb-1981 How One Man Traced His Ancestry Kenneth Merique's mission for 23 years NE Detroiter HW Herald BG 16-Apr-1982 One the Macomb Scene Polish Queen Miss Polish Festival 1982 contest Macomb Daily BG no date Publications on Parental Responsibilities of Raising Children Responsibilities of a Sunday School E.T.T.A. BG 1976 1981 General Outline of the New Testament Rulers of Palestine during Jesus Life, Times Acts Moody Bible Inst. Chicago BG 15-29 May 1982 In Memory of Assumption Grotto Church 150th Anniversary Pilgrimage to Italy Joannes Paulus PP II BG Spring 1985 Edmund Szoka Memorial Card unknown BG no date Copy of Genesis 3.21 - 4.6 Adam Eve Cain Abel Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.7- 4.25 First Civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 4.26 - 5.30 Family of Seth Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 5.31 - 6.14 Flood Cainites Sethites antediluvian civilization Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 9.8 - 10.2 Noah, Shem, Ham, Japheth, Ham father of Canaan Holy Bible BG no date Copy of Genesis 10.3 - 11.3 Sons of Gomer, Sons of Javan, Sons -

Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right

“Artisans … for Antichrist”: Jews, Radical Catholic Traditionalists, and the Extreme Right Mark Weitzman* The Israeli historian, Israel J. Yuval, recently wrote: The Christian-Jewish debate that started nineteen hundred years ago, in our day came to a conciliatory close. … In one fell swoop, the anti-Jewish position of Christianity became reprehensible and illegitimate. … Ours is thus the first generation of scholars that can and may discuss the Christian-Jewish debate from a certain remove … a post- polemical age.1 This appraisal helped spur Yuval to write his recent controversial book Two Nations in Your Womb: Perceptions of Jews and Christians in late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Yuval based his optimistic assessment on the strength of the reforms in Catholicism that stemmed from the adoption by the Second Vatican Council in 1965 of the document known as Nostra Aetate. Nostra Aetate in Michael Phayer’s words, was the “revolution- ary” document that signified “the Catholic church’s reversal of its 2,000 year tradition of antisemitism.”2 Yet recent events in the relationship between Catholics and Jews could well cause one to wonder about the optimism inherent in Yuval’s pronouncement. For, while the established Catholic Church is still officially committed to the teachings of Nostra Aetate, the opponents of that document and of “modernity” in general have continued their fight and appear to have gained, if not a foothold, at least a hearing in the Vatican today. And, since in the view of these radical Catholic traditionalists “[i]nternational Judaism wants to radically defeat Christianity and to be its substitute” using tools like the Free- * Director of Government Affairs, Simon Wiesenthal Center. -

The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, Et Al

Consensus Volume 26 Article 7 Issue 2 Apocalyptic 11-1-2000 The iuP s XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al Oscar Cole-Arnal Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Cole-Arnal, Oscar (2000) "The iusP XII controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et al," Consensus: Vol. 26 : Iss. 2 , Article 7. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol26/iss2/7 This Studies and Observations is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Pius XII Controversy: John Cornwell, Margherita Marchione, et. al. Oscar L. Cole-Arnal Professor of Historical Theology Waterloo Lutheran Seminary Waterloo, Ontario ew would dispute that Eugenio Pacelli, better known as Pope Pius XII, remains one of the most controversial figures of this Fcentury. Although his reign lasted twenty years (1939-1958), the debate swirls around his career as a papal diplomat in Germany from I 1917 to 1939 (the year he became pope) and the period of his papacy I i that overlapped with World War II. Questions surrounding his relation- ship with Hitler’s Third Reich (1933-1945) and his policy decisions with respect to the Holocaust extend far beyond the realm of calm historical research to the point of acrimonious polemics. In fact, virtually all the I studies which have emerged about Pius XII after the controversial play I The Deputy (1963) by Rolf Hochhuth range between histories with po- lemical elements to outright advocacy works for or against. -

Gottes Mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina Und Papst Pius XII

Martha Schad Gottes mächtige Dienerin Schwester Pascalina und Papst Pius XII. Mit 25 Fotos Herbig Für Schwester Dr. Uta Fromherz, Kongregation der Schwestern vom Heiligen Kreuz, Menzingen in der Schweiz Inhalt Teil I Inhaltsverzeichnis/Leseprobe aus dem Verlagsprogramm der 1894–1929 Buchverlage LangenMüller Herbig nymphenburger terra magica In der Nuntiatur in München und Berlin Bitte beachten Sie folgende Informationen: Von Ebersberg nach Altötting 8 Der Inhalt dieser Leseprobe ist urheberrechtlich geschützt, Im Dienst für Nuntius Pacelli in München und Berlin 20 alle Rechte liegen bei der F. A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München. Die Leseprobe ist nur für den privaten Gebrauch bestimmt und darf nur auf den Internet-Seiten www.herbig.net, Teil II www.herbig-verlag.de, www.langen-mueller-verlag.de, 1930–1939 www.nymphenburger-verlag.de, www.signumverlag.de und www.amalthea-verlag.de Im Vatikan mit dem direkt zum Download angeboten werden. Kardinalstaatssekretär Pacelli Die Übernahme der Leseprobe ist nur mit schriftlicher Genehmigung des Verlags Besuchen Sie uns im Internet unter: Der vatikanische Haushalt 50 gestattet. Die Veränderungwww d.heer digitalenrbig-verlag Lese.deprobe ist nicht zulässig. Reisen mit dem Kardinalstaatssekretär 67 »Mit brennender Sorge«, 1937 85 © 2007 by F.A. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, München Alle Rechte vorbehalten Umschlaggestaltung: Wolfgang Heinzel Teil III Umschlagbild: Hans Lehnert, München 1939–1958 und dpa/picture-alliance, Frankfurt Lektorat: Dagmar von Keller Im Vatikan mit Papst Pius XII. Herstellung und Satz: VerlagsService Dr. Helmut Neuberger & Karl Schaumann GmbH, Heimstetten Judenverfolgung, Hunger und Not 94 Gesetzt aus der 11,5/14,5 Punkt Minion Das päpstliche Hilfswerk – Michael Kardinal Drucken und Binden: GGP Media GmbH, Pößneck Printed in Germany von Faulhaber 110 ISBN 978-3-7766-2531-8 Mächtige Hüterin 146 Teil IV 1959–1983 Oberin am päpstlichen nordamerikanischen Priesterkolleg in Rom Der vatikanische Haushalt Leben ohne Papst Pius XII.