Snakebite Envenomization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

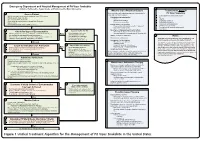

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Approach to the Poisoned Patient

PED-1407 Chocolate to Crystal Methamphetamine to the Cinnamon Challenge - Emergency Approach to the Intoxicated Child BLS 08 / ALS 75 / 1.5 CEU Target Audience: All Pediatric and adolescent ingestions are common reasons for 911 dispatches and emergency department visits. With greater availability of medications and drugs, healthcare professionals need to stay sharp on current trends in medical toxicology. This lecture examines mind altering substances, initial prehospital approach to toxicology and stabilization for transport, poison control center resources, and ultimate emergency department and intensive care management. Pediatric Toxicology Dr. James Burhop Pediatric Emergency Medicine Children’s Hospital of the Kings Daughters Objectives • Epidemiology • History of Poisoning • Review initial assessment of the child with a possible ingestion • General management principles for toxic exposures • Case Based (12 common pediatric cases) • Emerging drugs of abuse • Cathinones, Synthetics, Salvia, Maxy/MCAT, 25I, Kratom Epidemiology • 55 Poison Centers serving 295 million people • 2.3 million exposures in 2011 – 39% are children younger than 3 years – 52% in children younger than 6 years • 1-800-222-1222 2011 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System Introduction • 95% decline in the number of pediatric poisoning deaths since 1960 – child resistant packaging – heightened parental awareness – more sophisticated interventions – poison control centers Epidemiology • Unintentional (1-2 -

Snake Bite Prevention What to Do If You Are Bitten

SNAKE BITE PREVENTION It has been estimated that 7,000–8,000 people per year are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States, and for around half a dozen people, these bites are fatal. In 2015, poison centers managed over 3,000 cases of snake and other reptile bites during the summer months alone. Approximately 80% of these poison center calls originated from hospitals and other health care facilities. Venomous snakes found in the U.S. include rattlesnakes, copperheads, cottonmouths/water moccasins, and coral snakes. They can be especially dangerous to outdoor workers or people spending more time outside during the warmer months of the year. Most snakebites occur when people accidentally step on or come across a snake, frightening it and causing it to bite defensively. However, by taking extra precaution in snake-prone environments, many of these bites are preventable by using the following snakebite prevention tips: Avoid surprise encounters with snakes: Snakes tend to be active at night and in warm weather. They also tend to hide in places where they are not readily visible, so stay away from tall grass, piles of leaves, rocks, and brush, and avoid climbing on rocks or piles of wood where a snake may be hiding. When moving through tall grass or weeds, poke at the ground in front of you with a long stick to scare away snakes. Watch where you step and where you sit when outdoors. Shine a flashlight on your path when walking outside at night. Wear protective clothing: Wear loose, long pants and high, thick leather or rubber boots when spending time in places where snakes may be hiding. -

![Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0546/bites-and-stings-poisonous-animals-and-plants-720546.webp)

Bites and Stings [Poisonous Animals and Plants]

Poisonous animals and plants Dr Tim Healing Dip.Clin.Micro, DMCC, CBIOL, FZS, FRSB Course Director, Course in Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Worshipful Society of Apothecaries of London Faculty of Conflict and Catastrophe Medicine Animal and plant toxins • In most instances the numbers of people affected will be small • There are a few instances where larger numbers may be involved – mainly due to food-borne toxins Poisonous species (N.B. Venomous species use poisons for attack, poisonous animals and plants for passive defence) Venomous and poisonous animals – Reptiles (snakes) – Amphibians (dart frogs) – Arthropods (scorpions, spiders, wasps, bees, centipedes) – Aquatic animals (fish, jellyfish, octopi) Poisonous plants – Contact stinging (nettles, poison ivy, algae) – Poisonous by ingestion (fungi, berries of some plants) – Some algae Snakes Venomous Snakes • About 600 species of snake are venomous (ca. 25% of all snake species). Four main groups: – Elapidae (elapids). Mambas, Cobras, King cobras, Kraits, Taipans, Sea snakes, Brown snakes, Coral snakes. – Viperidae (viperids). True vipers and pit vipers (including Rattlesnakes, Copperheads and Cottonmouths) – Colubridae (colubrids). Mostly harmless, but includes the Boomslang – Atractaspididae (atractaspidids). Burrowing asps, Mole vipers, Stiletto snakes. Geographical distribution • Elapidae: – On land, worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, except in Europe. – Sea snakes occur in the Indian Ocean and the Pacific • Viperidae: – The Americas, Africa and Eurasia. • Boomslangs -

Venom Week 2012 4Th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous

17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology Animal, Plant and Microbial Toxins & Venom Week 2012 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012 1 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction 01 Scientific Organizing Committee 02 Local Organizing Committee / Sponsors / Co-Chairs 02 Welcome Messages 04 Governor’s Proclamation 08 Meeting Program 10 Sunday 13 Monday 15 Tuesday 20 Wednesday 26 Thursday 30 Friday 36 Poster Session I 41 Poster Session II 47 Supplemental program material 54 Additional Abstracts (#298 – #344) 61 International Society on Thrombosis & Haemostasis 99 2 Introduction Welcome to the 17th World Congress of the International Society on Toxinology (IST), held jointly with Venom Week 2012, 4th International Scientific Symposium on All Things Venomous, in Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, July 8 – 13, 2012. This is a supplement to the special issue of Toxicon. It contains the abstracts that were submitted too late for inclusion there, as well as a complete program agenda of the meeting, as well as other materials. At the time of this printing, we had 344 scientific abstracts scheduled for presentation and over 300 attendees from all over the planet. The World Congress of IST is held every three years, most recently in Recife, Brazil in March 2009. The IST World Congress is the primary international meeting bringing together scientists and physicians from around the world to discuss the most recent advances in the structure and function of natural toxins occurring in venomous animals, plants, or microorganisms, in medical, public health, and policy approaches to prevent or treat envenomations, and in the development of new toxin-derived drugs. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Snakebite and Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2013

Guideline Ministry of Health, NSW 73 Miller Street North Sydney NSW 2060 Locked Mail Bag 961 North Sydney NSW 2059 Telephone (02) 9391 9000 Fax (02) 9391 9101 http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/ space space Snakebite and Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2013 - Third Edition space Document Number GL2014_005 Publication date 17-Mar-2014 Functional Sub group Clinical/ Patient Services - Critical care Clinical/ Patient Services - Medical Treatment Summary Revised clinical resource document which provides information and advise on the management of patients with actual or suspected snakebite or spiderbite, and the appropriate levels, type and location of stored antivenom in NSW health facilities. These are clinical guidelines for best clinical practice which are not mandatory but do provide essential clinical support. Replaces Doc. No. Snakebite & Spiderbite Clinical Management Guidelines 2007 - NSW [GL2007_006] Author Branch Agency for Clinical Innovation Branch contact Agency for Clinical Innovation 9464 4674 Applies to Local Health Districts, Board Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Chief Executive Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Specialty Network Governed Statutory Health Corporations, Affiliated Health Organisations, Community Health Centres, Government Medical Officers, NSW Ambulance Service, Ministry of Health, Private Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, Public Health Units, Public Hospitals Audience Clinicial Nursing, Medical, Allied Health Staff, Administration, ED, Intensive Care Units Distributed to Public Health System, Divisions of General Practice, Government Medical Officers, Ministry of Health, Private Hospitals and Day Procedure Centres, Tertiary Education Institutes Review date 17-Mar-2019 Policy Manual Patient Matters File No. 12/4133 Status Active Director-General FIVE Spiderbite Guidelines for Assessment and Management Introduction Red-back spider envenoming or latrodectism is Specific features of funnel-web and red back bite are characterised by severe local or regional pain associated discussed below. -

Venomous Snakebites in the United States

CLINICAL REVIEW Venomous Snakebites in the United States Bernard A. Kurecki III, MD, and H. James Brownlee, Jr., MD St. Petersburg, Florida Venomous snakebite treatment is controversial. Venomous snakebites are known to occur in all but a few states. Approximately 10 to 15 individuals die from snake bites each year, with bites from diamondback rattlesnakes accounting for 95 per cent of fatalities. The identification of the two endogenous classes of venomous snakes are discussed in detail to aid in determining the proper treatment for each class. Approximately 25 percent of all pit viper bites are “ dry" and result in no envenomation. The best first aid is a set of car keys to get the victim to a facility where anti- venin is obtainable. Incision and suction should be limited to very special situa tions; cryotherapy and use of tourniquets applied by laymen should be avoided. Proper medical management at a health care facility requires establishing whether envenomation has occurred and to what extent, followed by appropriate dosing of antivenin. The use of corticosteroids and antibiotics is controversial. Tetanus im munization should be updated, if necessary. Although research in developing a more purified antivenin is under way, the best treatment for snakebite is preven tion. venomous snakebite—rarely does any subject draw snakes and refuse treatment in the hope that their religious A more attention and controversy in an emergency de beliefs will effect a cure for the snakebite. partment. Frequently two or more proponents of different Approximately 75 percent of all snakebites occur in treatments may feel the need to defend zealously their people aged between 19 and 30 years, 1 percent to 2 per specific school of thought, and anyone who attempts even cent occur in women, and less than 1 percent occur in the simplest care of a venomous snakebite may be called blacks. -

PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases Broadens Its Coverage of Envenomings Caused by Animal Bites and Stings

EDITORIAL PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases broadens its coverage of envenomings caused by animal bites and stings 1 2,3 4 Jose MarõÂa GutieÂrrezID *, Jean Philippe ChippauxID , Geoffrey K. IsbisterID 1 Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Universidad de Costa Rica, San JoseÂ, Costa Rica, 2 Universite de Paris, MERIT, IRD, Paris, France, 3 CRT, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France, 4 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia * [email protected] Envenomings from animal bites and stings are particularly frequent in developing countries where they dramatically affect the most deprived populations. A wide variety of animals from different taxa synthesize and inject venoms either as a trophic mechanism to subdue and digest prey or as a defense against predators and other enemies. These toxic secretions can also be injected into humans or domestic animals and significantly impact human and veterinary a1111111111 health. Bites by venomous snakes cause 1.8 to 2.7 million cases of envenomings every year, a1111111111 with 81,000 to 138,000 fatalities, and, possibly, leaving more people with permanent physical a1111111111 and psychological sequelae [1]. This burden of illness largely occurs in impoverished rural a1111111111 populations in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America. In addition, snakebite has a heavy a1111111111 socioeconomic impact, because it predominantly affects the young working population in low- and middle-income countries [2]. For these reasons, snakebite envenoming is included in the list of neglected tropical diseases of the World Health Organization. As one of the foremost journals in tropical medicine and neglected tropical diseases, PLOS OPEN ACCESS Neglected Tropical Diseases has regularly published contributions on various aspects of snake- Citation: GutieÂrrez JM, Chippaux JP, Isbister GK bite and snake envenoming for over a decade. -

Snakebite: the World's Biggest Hidden Health Crisis

Snakebite: The world's biggest hidden health crisis Snakebite is a potentially life-threatening neglected tropical disease (NTD) that is responsible for immense suffering among some 5.8 billion people who are at risk of encountering a venomous snake. The human cost of snakebite Snakebite Treatment Timeline Each year, approximately 5.4 million people are bitten by a snake, of whom 2.7 million are injected with venom. The first snake antivenom This leads to 400,000 people being permanently dis- produced, against the Indian Cobra. abled and between 83,000-138,000 deaths annually, Immunotherapy with animal- mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. 1895 derived antivenom has continued to be the main treatment for snakebite evenoming for 120 years Snakebite: both a consequence and a cause of tropical poverty The Fav-Afrique antivenom, 2014 produced by Sanofi Pasteur (France) Survivors of untreated envenoming may be left with permanently discontinued amputation, blindness, mental health issues, and other forms of disability that severely affect their productivity. World Health Organization Most victims are agricultural workers and children in 2018 (WHO) lists snakebite envenoming the poorest parts of Africa and Asia. The economic as a neglected tropical disease cost of treating snakebite envenoming is unimaginable in most communities and puts families and communi- ties at risk of economic peril just to pay for treatment. WHO launches a strategy to prevent and control snakebite envenoming, including a program targeting affected communities and their health systems Global antivenom crisis 2019 The world produces less than half of the antivenom it The Scientific Research Partnership needs, and this only covers 57% of the world’s species for Neglected Tropical Snakbites of venomous snake. -

Ingestions, Intoxications, and the Critically Ill Child Poisoning in Children

Ingestions, Intoxications, and the Critically Ill Child Poisoning in Children • 1 million cases of exposure to toxins in children younger than 6 years reported in the U.S. In 1993 • estimated that another 1 million exposures to toxins not reported • 1% have moderate or major life-threatening symptoms • 60-100 deaths annually in the U.S Poisoning in Children Less Than 5 Years Old • accounts for 85-90% of pediatric poisoning • is generally accidental • secondary to exploratory behavior and lack of supervision • tend to involve single agent ingestions Poisoning in Children Over 5 Years Old • accounts for 10-15% of pediatric poisoning • is generally intentional • secondary to suicide attempts or gestures, or to intoxications and inadvertent overdose • tend to involve multiple agent ingestions General Concepts for Pediatric Poisoning • Prevention • Initial Stabilization • Diagnosis • Specific Antidotes Management of the Poisoned Child • Treat the Patient, Not the Poison --patient-specific treatment is safer, less expensive, and more effective Management of the Poisoned Child • Stabilization --Airway --Breathing --Circulation --Disability (neurologic) Management of the Poisoned Child • Respiratory Failure --airway obstruction from secretions, refluxed gastric contents, airway muscle relaxation --respiratory muscle rigidity --loss of respiratory drive --pulmonary edema Management of the Poisoned Child • Cardiovascular Collapse --arteriolar dilation --venous dilation --myocardial depression --dysrhythmias Management of the Poisoned Child • Neurologic -

Factors Affecting Prognosis in Patients with Snakebite

EURASIAN JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICINE DO I: 10.4274/eajem.galenos.2020.69885 Original Article Eurasian J Emerg Med. 2021;20(1): 6-11 Factors Affecting Prognosis in Patients with Snakebite Mehmet Özbulat, Ayca Açıkalın, Ufuk Akday, Ömer Taşkın, Nezihat Rana Dişel, Ahmet Sebe Department of Emergency Medicine, Çukurova University Faculty of Medicine, Adana, Turkey Abstract Aim: This study aimed to determine the factors influencing hospitalization durations and discharge status of patients with snakebite, starting from pre-hospital care in the field. Materials and Methods: A total of 38 patients with snakebite admitted to the emergency medicine department between May 1st, 2013 and August 31st, 2016, participated in the study. Data were evaluated using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 17.0. Results: A total of 38 patients were enrolled, of which, 17 (44.7%) were female. Of the 38 patients enrolled, nine patients were in stage 1, 24 in stage 2, and 5 in stage 3. The mean antivenoms given to patients were 3.33±1.29 vials in stage 2 and 4.40±1.14 vials in stage 3. The mean time from bite to antivenom infusion was 80.92±47.57 mins. Hospitalization durations of patients with shorter bite to antivenom infusion intervals (bite-to-needle) were also shorter (p<0.001). In addition, overweight patients were found to stay longer in the hospital (p=0.027). Patients with low hemoglobin and platelet counts and high creatine kinase (CK) levels were found to stay longer in the hospital (p<0.05). Conclusion: Shorter hospitalization durations of patients with shorter bite-to-needle times show the importance of early administration of antivenom.