The History of Winchcombe Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Musings from Your Parish Priest

SAINTS FOR THE YEAR OF THE EUCHARIST WELCOME TO ST. PETER JULIAN EYMARD St. Peter Julian Eymard was a 19th century CATHOLIC CHURCH French priest whose devotion to the Blessed Sacra- ment expressed itself both in mystical writings and the foundation of the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament, a religious institute designed to spread 2ND SUNDAY OF LENT - FEBRUARY 28TH, 2020 devotion to the Eucharist. Throughout his life, Peter Julian was afflicted Musings from your Parish Priest: by medical problems, including a “weakness of the In ancient times, the obligation of the penitential fast throughout Lent was to take only one full lungs” and recurrent migraines. He sought solace meal a day. In addition, a smaller meal, called a collation, was allowed in the evening. In practice, this for his suffering in devotion to both Mary and the obligation, which was a matter of custom rather than of written law, was not observed Blessed Sacrament, having originally been a mem- strictly. The 1917 Code of Canon Law allowed the full meal on a fasting day to be taken at any hour ber of the Society of Mary. While serving as visitor and to be supplemented by two collations, with the quantity and the quality of the food to be -general of the society, he observed Marian com- determined by local custom. Abstinence from meat was to be observed on Ash Wednesday and on munities near Paris who practiced perpetual adora- Fridays and Saturdays in Lent. A rule of thumb is that the two collations should not add up to the tion, and was moved by the devotion and happi- equivalent of another full meal. -

BLEDINGTON FOXHOLES and FOSCOT NEWS March 2021 No 444

1 BLEDINGTON FOXHOLES AND FOSCOT NEWS March 2021 No 444 Wandering amongst the tens of thousands of snowdrops at Colesbourne Park with the blue coloured water in the lake reflecting the clay minerals in the water. 2 DATES FOR YOUR DIARY MARCH 2021 Mondays and Fridays; Post Office, Oddington Vill. Hall (p 3) 10.30 to 12.00 Monday 1 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Grey Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Monday 1 Bledington Parish Council Meeting (ZOOM) (p 12) 8.00pm Tuesday 2 Bledington CDC Recycling Day (p 17) 7.00am Monday 8 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Green Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Wednesday 10 Egyptian Art, Walls and Murals (p 13) 10.30am Monday 15 Foxholes/Foscot Grey Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Tuesday 16 Bledington CDC Recycling Day (p 17) 7.00am Wednesday 17 Music in European Art Collections (p 13) 10.30am Monday 22 Foxholes/Foscot WODC Green Collection Day (p 17) 6.00am Tuesday 23 BLEDINGTON NEWS COPY DEADLINE (p 2) 12.00noon Sunday 28 CLOCKS GO FORWARD ONE HOUR 1.00am WE WELCOME NEWS CONTRIBUTIONS TO BLEDINGTON, FOXHOLES AND FOSCOT NEWS Please send your news contributions for the next Issue at any time. Copy deadline is strictly 12.00 Noon 23rd of each month (January to November). Please send news contributions for Bledington News to the editors, Wendy and Sinclair Scott, by paper copy to 4 Old Forge Close, Bledington, Chipping Norton, OX7 6XW or email us at [email protected] Tel: 01608 658624. Bledington News is published in full colour at www.bledington.com Please ensure you have a prompt acknowledgement of your contribution sent by email; this makes it certain we have received it. -

How Useful Are Episcopal Ordination Lists As a Source for Medieval English Monastic History?

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. , No. , July . © Cambridge University Press doi:./S How Useful are Episcopal Ordination Lists as a Source for Medieval English Monastic History? by DAVID E. THORNTON Bilkent University, Ankara E-mail: [email protected] This article evaluates ordination lists preserved in bishops’ registers from late medieval England as evidence for the monastic orders, with special reference to religious houses in the diocese of Worcester, from to . By comparing almost , ordination records collected from registers from Worcester and neighbouring dioceses with ‘conven- tual’ lists, it is concluded that over per cent of monks and canons are not named in the extant ordination lists. Over half of these omissions are arguably due to structural gaps in the surviving ordination lists, but other, non-structural factors may also have contributed. ith the dispersal and destruction of the archives of religious houses following their dissolution in the late s, many docu- W ments that would otherwise facilitate the prosopographical study of the monastic orders in late medieval England and Wales have been irre- trievably lost. Surviving sources such as the profession and obituary lists from Christ Church Canterbury and the records of admissions in the BL = British Library, London; Bodl. Lib. = Bodleian Library, Oxford; BRUO = A. B. Emden, A biographical register of the University of Oxford to A.D. , Oxford –; CAP = Collectanea Anglo-Premonstratensia, London ; DKR = Annual report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records, London –; FOR = Faculty Office Register, –, ed. D. S. Chambers, Oxford ; GCL = Gloucester Cathedral Library; LP = J. S. Brewer and others, Letters and papers, foreign and domestic, of the reign of Henry VIII, London –; LPL = Lambeth Palace Library, London; MA = W. -

Secondary School and Academy Admissions

Secondary School and Academy Admissions INFORMATION BOOKLET 2021/2022 For children born between 1st September 2009 and 31st August 2010 Page 1 Schools Information Admission number and previous applications This is the total number of pupils that the school can admit into Year 7. We have also included the total number of pupils in the school so you can gauge its size. You’ll see how oversubscribed a school is by how many parents had named a school as one of their five preferences on their application form and how many of these had placed it as their first preference. Catchment area Some comprehensive schools have a catchment area consisting of parishes, district or county boundaries. Some schools will give priority for admission to those children living within their catchment area. If you live in Gloucestershire and are over 3 miles from your child’s catchment school they may be entitled to school transport provided by the Local Authority. Oversubscription criteria If a school receives more preferences than places available, the admission authority will place all children in the order in which they could be considered for a place. This will strictly follow the priority order of their oversubscription criteria. Please follow the below link to find the statistics for how many pupils were allocated under the admissions criteria for each school - https://www.gloucestershire.gov.uk/education-and-learning/school-admissions-scheme-criteria- and-protocol/allocation-day-statistics-for-gloucestershire-schools/. We can’t guarantee your child will be offered one of their preferred schools, but they will have a stronger chance if they meet higher priorities in the criteria. -

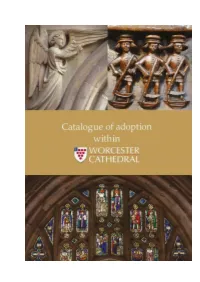

Catalogue of Adoption Items Within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window

Catalogue of Adoption Items within Worcester Cathedral Adopt a Window The cloister Windows were created between 1916 and 1999 with various artists producing these wonderful pictures. The decision was made to commission a contemplated series of historical Windows, acting both as a history of the English Church and as personal memorials. By adopting your favourite character, event or landscape as shown in the stained glass, you are helping support Worcester Cathedral in keeping its fabric conserved and open for all to see. A £25 example Examples of the types of small decorative panel, there are 13 within each Window. A £50 example Lindisfarne The Armada A £100 example A £200 example St Wulfstan William Caxton Chaucer William Shakespeare Full Catalogue of Cloister Windows Name Location Price Code 13 small decorative pieces East Walk Window 1 £25 CW1 Angel violinist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW2 Angel organist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW3 Angel harpist East Walk Window 1 £50 CW4 Angel singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW5 Benedictine monk writing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW6 Benedictine monk preaching East Walk Window 1 £50 CW7 Benedictine monk singing East Walk Window 1 £50 CW8 Benedictine monk East Walk Window 1 £50 CW9 stonemason Angel carrying dates 680-743- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW10 983 Angel carrying dates 1089- East Walk Window 1 £50 CW11 1218 Christ and the Blessed Virgin, East Walk Window 1 £100 CW12 to whom this Cathedral is dedicated St Peter, to whom the first East Walk Window 1 £100 CW13 Cathedral was dedicated St Oswald, bishop 961-992, -

ST EDMUND Dedicated to St Edmund and All the Bright Spirits of Old England Who Bring Comfort and Growing Hope That All the Wrong Shall Yet Be Made Right

THE LIGHT FROM THE EAST: ENGLAND’S LOST PATRON SAINT: ST EDMUND Dedicated to St Edmund and all the Bright Spirits of Old England Who Bring Comfort and Growing Hope That all the Wrong Shall Yet Be Made Right. by Fr Andrew Phillips CONTENTS: Foreword Prologue: Seven Kingdoms and East Anglia Chapter One: Childhood of a King Chapter Two: Edmund’s Kingdom Chapter Three: Edmund’s Martyrdom Chapter Four: Sainthood of a King Epilogue: One Kingdom and Anglia Appendix Bibliography To Saint Edmund This booklet was originally published in parts in the first volume of Orthodox England (1997–1998). This online edition has been revised by Fr Andrew Phillips and reformatted by Daysign, 2020. The Light from the East: England’s Lost Patron Saint: St Edmund Foreword FOREWORD Tis a sad fact, illustrative of our long disdain and neglect of St Edmund 1, formerly much revered as the Patron Saint of England, that to this day there exists no Life of Ithe Saint which is readable, reliable and accessible to the modern reader. True, there is the Life written in Ramsey by St Abbo of Fleury over a thousand years ago in c. 985. Written in Latin but translated shortly afterwards into Old English by that most orthodox monk Ælfric, it is based on an eyewitness account. We think it reliable, but it is not accessible and it covers only a short period of the Saint’s life. True, a great many mediæval chroniclers wrote of St Edmund, among them – Hermann of Bury StEdmunds, Symeon of Durham, Geoffrey Gaimar, Geoffrey of Wells, William of Malmesbury, Osbert of Clare, Florence of Worcester, Jocelin of Brakelond, William of Ramsey, Henry of Huntingdon, Ingulf of Crowland, Matthew Paris, Roger of Wendover, Denis Piramus, Richard of Cirencester and John Lydgate. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

The Bishop of Winchester's Deer Parks in Hampshire, 1200-1400

Proc. Hampsk. Field Club Archaeol. Soc. 44, 1988, 67-86 THE BISHOP OF WINCHESTER'S DEER PARKS IN HAMPSHIRE, 1200-1400 By EDWARD ROBERTS ABSTRACT he had the right to hunt deer. Whereas parks were relatively small and enclosed by a park The medieval bishops of Winchester held the richest see in pale, chases were large, unfenced hunting England which, by the thirteenth century, comprised over fifty grounds which were typically the preserve of manors and boroughs scattered across six southern counties lay magnates or great ecclesiastics. In Hamp- (Swift 1930, ix,126; Moorman 1945, 169; Titow 1972, shire the bishop held chases at Hambledon, 38). The abundant income from his possessions allowed the Bishop's Waltham, Highclere and Crondall bishop to live on an aristocratic scale, enjoying luxuries (Cantor 1982, 56; Shore 1908-11, 261-7; appropriate to the highest nobility. Notable among these Deedes 1924, 717; Thompson 1975, 26). He luxuries were the bishop's deer parks, providing venison for also enjoyed the right of free warren, which great episcopal feasts and sport for royal and noble huntsmen. usually entitled a lord or his servants to hunt More deer parks belonged to Winchester than to any other see in the country. Indeed, only the Duchy of Lancaster and the small game over an entire manor, but it is clear Crown held more (Cantor et al 1979, 78). that the bishop's men were accustomed to The development and management of these parks were hunt deer in his free warrens. For example, recorded in the bishopric pipe rolls of which 150 survive from between 1246 and 1248 they hunted red deer the period between 1208-9 and 1399-1400 (Beveridge in the warrens of Marwell and Bishop's Sutton 1929). -

Chertsey Abbey : an Existence of the Past

iii^li.iin H.xik i ... l.t.l loolcsdlen and K.M kliin.l : .. Vil-rTii Str.-t. NOTTINGHAM. |. t . tft <6;ri0fence of Photo, by F. A. Monk. [Frontispiece. TRIPTYCH OF TILES FROM CHERTSEY ABBEY, THIRTEENTH CENTURY. of BY LUCY WHEELER. With. Preface by SIR SWINFEN EADY. ARMS OF THE MONASTERY OF S. PETER, ABBEY CHURCH, CHERTSEY. Bonbon : WELLS GARDNER, DARTON & CO., LTD., 3, Paternoster Buildings, E.C., and 44, Victoria Street, S. W. PREFACE THE History of Chertsey Abbey is of more than local interest. Its foundation carries us back to so remote a period that the date is uncertain. The exact date fixed in the is A.D. but Chertsey register 666 ; Reyner, from Capgrave's Life of S. Erkenwald, will have this Abbey to have been founded as early as A.D. 630. That Erken- wald, however, was the real founder, and before he became Bishop of London, admits of no doubt. Even the time of Erkenwald's death is not certain, some placing it in 685, while Stow says he died in 697. His splendid foundation lasted for some nine centuries, and in the following pages will be found a full history of the Abbey and its rulers and possessions until its dissolution by Henry VIII. is incessant is con- Change everywhere, and ; nothing stant or in a or less stable, except greater degree ; the Abbeys which in their time played so important a part in the history and development of the country, and as v houses of learning, have all passed away, but a study of the history of an important Abbey enables us to appre- ciate the part which these institutions played in the past, and some of the good they achieved, although they were not wholly free from abuses. -

Gloucester Cathedral Faith, Art and Architecture: 1000 Years

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL FAITH, ART AND ARCHITECTURE: 1000 YEARS SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING SUPPLIED BY THE AUTHORS CHAPTER 1 ABBOT SERLO AND THE NORMAN ABBEY Fernie, E. The Architecture of Norman England (Oxford University Press, 2000). Fryer, A., ‘The Gloucestershire Fonts’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 31 (1908), pp 277-9. Available online at http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v031/bg031277.pdf Hare, M., ‘The two Anglo-Saxon minsters of Gloucester’. Deerhurst lecture 1992 (Deerhurst, 1993). Hare, M., ‘The Chronicle of Gregory of Caerwent: a preliminary account, Glevensis 27 (1993), pp. 42-4. Hare, M., ‘Kings Crowns and Festivals: the Origins of Gloucester as a Royal Ceremonial Centre’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 115 (1997), pp. 41-78. Hare, M., ‘Gloucester Abbey, the First Crusade and Robert Curthose’, Friends of Gloucester Cathedral Annual Report 66 (2002), pp. 13-17. Heighway, C., ‘Gloucester Cathedral and Precinct: an archaeological assessment’. Third edition, produced for incorporation in the Gloucester Cathedral Conservation Plan (2003). Available online at http://www.bgas.org.uk/gcar/index.php Heighway, C. M., ‘Reading the stones: archaeological recording at Gloucester Cathedral’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 126 (2008), pp. 11-30. McAleer, J.P., The Romanesque Church Façade in Britain (New York and London: Garland, 1984). Morris R. K., ‘Ballflower work in Gloucester and its vicinity’, Medieval Art and Architecture at Gloucester and Tewkesbury. British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the year 1981 (1985), pp. 99-115. Thompson, K., ‘Robert, duke of Normandy (b. in or after 1050, d. -

The Pershore Flores Historiarum: an Unrecognised Chronicle from the Period of Reform and Rebellion in England, 1258–65*

English Historical Review Vol. CXXVII No. 529 doi:10.1093/ehr/ces311 © The Author [2012]. Published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved. The Pershore Flores Historiarum: An Unrecognised Chronicle from the Period of Reform and Rebellion in England, 1258–65* Historians of the period of reform and rebellion in England between 1258 and 1265 make extensive use of a chronicle called the Flores Historiarum.1 This is not surprising, because the Flores covers the revolution of 1258, the baronial regime of 1258–60, the king’s recovery of power in 1261, the civil war of 1263, the battle of Lewes in 1264, and the rule of Simon de Montfort down to his defeat and death at the battle of Evesham in 1265. In the earliest surviving text of the Flores, Downloaded from which belongs to Chetham’s Library in Manchester, the account of these revolutionary years is part of a longer section of the chronicle which begins in the year 1249. From that point, until the battle of Evesham in 1265, the text is unified, and distinguished from what comes before and after, by the way in which capital letters at the beginning of sections are http://ehr.oxfordjournals.org/ decorated and, in particular, by the decoration given to the letter ‘A’ in the ‘Anno’ at the beginning of each year.2 The text is also unified, and set apart, by being written, save for a short section at the start, in the same thirteenth-century hand and having very much the appearance of a fair copy.3 Historians who have studied the chronicle have nearly all assumed that this part of the Flores was copied at St Albans Abbey from 4 the work of Matthew Paris and his continuator. -

MASTER Conference Booklet Not BB

Welcome to Worcester College Oxford Dear Guest, Welcome to Worcester College. We are delighted you will be spending some time with us and will endeavour to do everything possible to make your visit both enjoy- able and memorable. We have compiled this directory of services and information, including information on Oxford city centre, which we hope you will find useful during your stay. A Short History There has been an educational establishment on the Worcester College site for over 725 years. In 1277 the General Chapter of the Benedictine Order in England established a house of study at Oxford, but nothing was done until 1283 when Gloucester Abbey founded a monastic house, endowed by Sir John Giffard, for the education of fifteen monks from the Gloucester community. The new foundation, occupying approximately the area around the present Main Quad, was outside the old city walls and adjacent to a Carmelite Friary founded in 1256. It was called Gloucester College, and it was the first and most important of the Benedictine colleges in Oxford. In 1291, the provincial chapter of the Benedictine order arranged for Gloucester College to become the house of study for young monks from Canterbury, and sixteen abbeys are recorded as having sent students here, mostly to study divinity and law. The first monk to graduate at the college, as a Bachelor of Divinity, was Dom William de Brock of Gloucester Abbey in 1298. These thirteenth-century houses were proudly called mansiones and are now referred to as the ‘Cottages’. Each has its own front door, staircase, and arms, or rebus, of the respective ruling abbot.