ARTICLES the House of Stolypin Migrants to Eastern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Economic and Geographical Characteristics and Prospects of Development of Environmental Protection Infrastructure in the Baikal Region of Russia

MODERN ECONOMIC AND GEOGRAPHICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND PROSPECTS OF DEVELOPMENT... QUAESTIONES GEOGRAPHICAE 30(2) • 2011 MODERN ECONOMIC AND GEOGRAPHICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND PROSPECTS OF DEVELOPMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE BAIKAL REGION OF RUSSIA TATIANA ZABORTSEVA Russian Academy of Sciences, Siberian Branch, V.B. Sochava Institute of Geography, Irkutsk, Russia Manuscript received February 15, 2011 Revised version June 8, 2011 ZABORTSEVA T. Modern economic and geographical characteristics and prospects of development of environmen- tal protection infrastructure in the Baikal region of Russia. Quaestiones Geographicae 30(2), Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Poznań 2011, pp. 81–86, 2 figs, 3 tables. DOI 10.2478/v10117-011-0020-2, ISBN 978-83-62662-62-3, ISSN 0137-477X. ABSTRACT : In the administrative division of Russia, the Baikal region is traditionally considered as embracing three parts: the Irkutsk oblast’, the Republic of Buryatia, and Zabaikalsky Kray. Its area is three times larger than that of France (1.6 million km²), but its population size and density are typical of “the Siberian depth of the coun- try” (4.6 million people, under 3 persons/km²). One of the most important global features of a part of this region – the Baikal Natural Territory – is to ensure the preservation of Lake Baikal as a World Heritage Site. A strategy of environmentally oriented land use determines an adequate level of development of ecological infrastructure and its most important sector – environmental protection infrastructure (EPI). The article presents an analysis of the current infrastructure for managing solid waste, and proposes a forecast scenario of its development with the use of the gravity model in the EPI sector involving recycling collection points. -

Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets Gluschenko, Konstantin Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk State University 2 April 2018 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85667/ MPRA Paper No. 85667, posted 02 Apr 2018 23:10 UTC Spatial Integration of Siberian Regional Markets Konstantin Gluschenko Institute of Economics and Industrial Engineering, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IEIE SB RAS), and Novosibirsk State University Novosibirsk, Russia E-mail address: [email protected] This paper studies market integration of 13 regions constituting Siberia with one another and all other Russian regions. The law of one price serves as a criterion of market integration. The data analyzed are time series of the regional costs of a basket of basic foods (staples basket) over 2001–2015. Pairs of regional markets are divided into four groups: perfectly integrated, conditionally integrated, not integrated but tending towards integration (converging), and neither integrated nor converging. Nonlinear time series models with asymptotically decaying trends describe price convergence. Integration of Siberian regional markets is found to be fairly strong; they are integrated and converging with about 70% of country’s regions (including Siberian regions themselves). Keywords: market integration, law of one price; price convergence; nonlinear trend; Russian regions. JEL classification: C32, L81, P22, R15 Prepared for the Conference “Economy of Siberia under Global Challenges of the XXI Century” dedicated to the 60th anniversary of the IEIE SB RAS; Novosibirsk, Russia, June 18–20, 2018. 1. Introduction The national product market is considered as a system with elements being its spatial segments, regional markets. -

Survey of Land and Real Estate Transactions in the Russian Federation

36117 V. 1 Public Disclosure Authorized Foreign Investment Advisory Service, Project is co-financed by the a joint service of the European Union International Finance Corporation in the framework of the and the World Bank Policy Advice Programme Public Disclosure Authorized SURVEY OF LAND AND REAL ESTATE TRANSACTIONS IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION CROSS-REGIONAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized March 2006 Public Disclosure Authorized Survey of Land and Real Estate Transactions in the Russian Federation. Cross-Regional Report The project has also received financial support from the Government of Switzerland, the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (seco). Report is prepared by the Media Navigator marketing agency, www.navigator,nnov.ru Disclaimer (EU) This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of its authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Disclaimer (FIAS) The Organizations (i.e. IBRD and IFC), through FIAS, have used their best efforts in the time available to provide high quality services hereunder and have relied on information provided to them by a wide range of other sources. However they do not make any representations or warranties regarding the completeness or accuracy of the information included this report, or the results which would be achieved by following its recommendations. 2 Survey of Land and Real Estate Transactions in the Russian Federation. Cross-Regional Report TABLE OF -

Estimations of Undisturbed Ground Temperatures Using Numerical and Analytical Modeling

ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING By LU XING Bachelor of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China 2008 Master of Arts/Science in Mechanical Engineering Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK, US 2010 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2014 ESTIMATIONS OF UNDISTURBED GROUND TEMPERATURES USING NUMERICAL AND ANALYTICAL MODELING Dissertation Approved: Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler Dissertation Adviser Dr. Daniel E. Fisher Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar Dr. Richard A. Beier ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Jeffrey D. Spitler, who patiently guided me through the hard times and encouraged me to continue in every stage of this study until it was completed. I greatly appreciate all his efforts in making me a more qualified PhD, an independent researcher, a stronger and better person. Also, I would like to devote my sincere thanks to my parents, Hongda Xing and Chune Mei, who have been with me all the time. Their endless support, unconditional love and patience are the biggest reason for all the successes in my life. To all my good friends, colleagues in the US and in China, who talked to me and were with me during the difficult times. I would like to give many thanks to my committee members, Dr. Daniel E. Fisher, Dr. Afshin J. Ghajar and Dr. Richard A. Beier for their suggestions which helped me to improve my research and dissertation. -

Annual Report 2007 Oao Irkutskenergo

ANNUAL REPORT 2007 OAO IRKUTSKENERGO Irkutsk 2007 ANNUAL REPORT IRKUTSK POWER GENERATION AND DISTRIBUTION COMPANY (OAO IRKUTSKENERGO) 2007 ANNUAL REPORT 3 ABBREVIATIONS BAM Baikal-Amur Mainline LV low voltage BHN Bratsk Heating Networks MBA Master of Business Administration BHPP Bratskaya Hydroelectric Power Plant MICEX Moscow Interbank Currency Exchange bn billion mln million BM balancing market MV medium voltage CHPP combined heat and power plant MW megawatt CMP Cost Management Program N-I CHPP Novo-Irkutskaya Combined Heat and Power Plant CPGD Central Power Grid District NKAZ Novokuznetsk Aluminium Smelter DAM day ahead market NOREM New Wholesale Electricity and Capacity Market (BM, DAM, LTBCM) EBITDA earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization NPGD Northern Power Grid District EPGD Eastern Power Grid District OAO open joint-stock company EPS earnings per share OOO limited liability company FST Federal Tariff s Service OPI overall performance improvement Gcal gigacalorie RAO UES of Russia RAO Unifi ed Energy System of Russia HND heating network district REC Regional Energy Commission HPP hydroelectric power plant ROA return on assets HR human resources ROE return on equity MAREM+ Interregional Agency of Electric Power and Capacity Market RTS Russian Trading System HV high voltage RF Russian Federation Hz hertz RUB Russian ruble IE OAO Irkutskenergo SPGD Southern Power Grid District IESK OOO Irkutsk Grid Company TCE tonne of coal equivalent IHPP Irkutskaya Hydroelectric Power Plant TPP thermal power plant IFRS International -

A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia

Informationen der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle für jüdische Architektur in Europa bet-tfila.org/info Nr. 18 1+2/15 Fakultät 3, Technische Universität Braunschweig / Center for Jewish Art, Hebrew University of Jerusalem SPECIAL EDITION “Siberia” – SONDERAUSGABE „Sibirien“ “From Jerusalem to Birobidzhan” – A Documentation of the Jewish Heritage in Siberia In August 2015, the team of the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University Erstmalig erscheint aus aktuellem Anlass of Jerusalem undertook a research expedition to Siberia. Over the course of 21 eine Sonderausgabe von bet tfila.org/info: Im days, the expedition spanned 6,000 km. Overall, the CJA team visited 16 sites August 2015 konnte sich das deutsch-israe- in Siberia and the Russian Far East: Tomsk, Mariinsk, Achinsk, Krasnoyarsk, lische Team des Center for Jewish Art und Kansk, Nizhneudinsk, Irkutsk, Babushkin (former Mysovsk), Kabansk, Ulan- der Bet Tfila – Forschungsstelle einen lange Ude (former Verkhneudinsk), Barguzin, Petrovsk Zabaikalskii (former Petrovskii gehegten Wunsch erfüllen und das jüdische Zavod), Chita, Khabarovsk, Birobidzhan, and Vladivostok. Erbe in Sibirien und im „Fernen Osten“ Russlands dokumentieren. In drei Wochen 16 synagogues and 4 collections of ritual objects were documented alongside a legten die fünf Wissenschaftler (Prof. Aliza survey of 11 Jewish cemeteries and numerous Jewish houses. The team consisted Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. of Prof. Aliza Cohen-Mushlin, Dr. Vladimir Levin, Dr. Katrin Kessler (Bet Tfila, Katrin Keßler, Dr. Anna Berezin und Archi- Braunschweig), Dr. Anna Berezin, and architect Zoya Arshavsky. The expedi- tektin Zoya Arshavsky) auf ihrer Reise von tion was made possible with the generous donations of Mrs. Josephine Urban, Tomsk nach Vladivostok über 6.000 km zu- London, and an anonymous donor. -

A Region with Special Needs the Russian Far East in Moscow’S Policy

65 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’s pOLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer NUMBER 65 WARSAW JUNE 2017 A REGION WITH SPECIAL NEEDS THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST IN MOSCOW’S POLICY Szymon Kardaś, additional research by: Ewa Fischer © Copyright by Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia / Centre for Eastern Studies CONTENT EDITOR Adam Eberhardt, Marek Menkiszak EDITOR Katarzyna Kazimierska CO-OPERATION Halina Kowalczyk, Anna Łabuszewska TRANSLATION Ilona Duchnowicz CO-OPERATION Timothy Harrell GRAPHIC DESIGN PARA-BUCH PHOTOgrAPH ON COVER Mikhail Varentsov, Shutterstock.com DTP GroupMedia MAPS Wojciech Mańkowski PUBLISHER Ośrodek Studiów Wschodnich im. Marka Karpia Centre for Eastern Studies ul. Koszykowa 6a, Warsaw, Poland Phone + 48 /22/ 525 80 00 Fax: + 48 /22/ 525 80 40 osw.waw.pl ISBN 978-83-65827-06-7 Contents THESES /5 INTRODUctiON /7 I. THE SPEciAL CHARActERISticS OF THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST AND THE EVOLUtiON OF THE CONCEPT FOR itS DEVELOPMENT /8 1. General characteristics of the Russian Far East /8 2. The Russian Far East: foreign trade /12 3. The evolution of the Russian Far East development concept /15 3.1. The Soviet period /15 3.2. The 1990s /16 3.3. The rule of Vladimir Putin /16 3.4. The Territories of Advanced Development /20 II. ENERGY AND TRANSPORT: ‘THE FLYWHEELS’ OF THE FAR EAST’S DEVELOPMENT /26 1. The energy sector /26 1.1. The resource potential /26 1.2. The infrastructure /30 2. Transport /33 2.1. Railroad transport /33 2.2. Maritime transport /34 2.3. Road transport /35 2.4. -

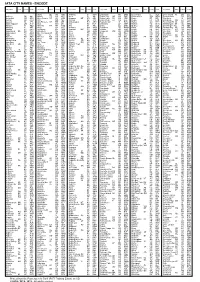

Iata City Names - Encode

IATA CITY NAMES - ENCODE City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code City name State Country Code Alpha QL AU ABH Aribinda BF XAR Bakelalan MY BKM Beersheba IL BEV Block Island RI US BID Aalborg DK AAL Alpine TX US ALE Arica CL ARI Baker City OR US BKE Befandriana MG WBD Bloemfontein ZA BFN Aalesund NO AES Alroy Downs NT AU AYD Aripuana MT BR AIR Baker Lake NU CA YBK Beica ET BEI Blonduos IS BLO Aarhus DK AAR Alta NO ALF Arkalyk KZ AYK Bakersfield CA US BFL Beida LY LAQ Bloodvein MB CA YDV Aasiaat GL JEG Alta Floresta MT BR AFL Arkhangelsk RU ARH Bakkafjordur IS BJD Beihai CN BHY Bloomfield Ri QL AU BFC Aba/Hongyuan CN AHJ Altai MN LTI Arlit NE RLT Bakouma CF BMF Beihan YE BHN Bloomington IN US BMG Abadan IR ABD Altamira PA BR ATM Arly BF ARL Baku AZ BAK Beijing CN BJS Bloomington-NIL US BMI Abaiang KI ABF Altay CN AAT Armenia CO AXM Balakovo RU BWO Beira MZ BEW Blubber Bay BC CA XBB Abakan XU ABA Altenburg DE AOC Armidale NS AU ARM Balalae SB BAS Beirut LB BEY Blue Bell PA US BBX Abbotsford BC CA YXX Altenrhein CH ACH Arno MH AMR Balgo Hill WA AU BQW Bejaia DZ BJA Bluefield WV US BLF Abbottabad PK AAW Alto Rio Seng CB AR ARR Aroa PG AOA Bali CM BLC Bekily MG OVA Bluefields NI BEF Abbs YE EAB Alton IL US ALN Arona SB RNA Bali PG BAJ Belaga MY BLG Blumenau SC BR BNU Abeche TD AEH Altoona PA US AOO Arorae KI AIS Balikesir TR BZI Belem PA BR BEL Blythe CA US BLH Abemama KI AEA Altus OK US LTS Arrabury QL AU AAB Balikpapan ID BPN Belfast GB -

Load Article

Arctic and North. 2018. No. 33 55 UDC [332.1+338.1](985)(045) DOI: 10.17238/issn2221-2698.2018.33.66 The prospects of the Northern and Arctic territories and their development within the Yenisei Siberia megaproject © Nikolay G. SHISHATSKY, Cand. Sci. (Econ.) E-mail: [email protected] Institute of Economy and Industrial Engineering of the Siberian Department of the Russian Academy of Sci- ences, Kransnoyarsk, Russia Abstract. The article considers the main prerequisites and the directions of development of Northern and Arctic areas of the Krasnoyarsk Krai based on creation of reliable local transport and power infrastructure and formation of hi-tech and competitive territorial clusters. We examine both the current (new large min- ing and processing works in the Norilsk industrial region; development of Ust-Eniseysky group of oil and gas fields; gasification of the Krasnoyarsk agglomeration with the resources of bradenhead gas of Evenkia; ren- ovation of housing and public utilities of the Norilsk agglomeration; development of the Arctic and north- ern tourism and others), and earlier considered, but rejected, projects (construction of a large hydroelectric power station on the Nizhnyaya Tunguska river; development of the Porozhinsky manganese field; place- ment of the metallurgical enterprises using the Norilsk ores near Lower Angara region; construction of the meridional Yenisei railroad and others) and their impact on the development of the region. It is shown that in new conditions it is expedient to return to consideration of these projects with the use of modern tech- nologies and organizational approaches. It means, above all, formation of the local integrated regional pro- duction systems and networks providing interaction and cooperation of the fuel and raw, processing and innovative sectors. -

Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities

Dr. K. Warikoo 1 © Vivekananda International Foundation 2020 Published in 2020 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg | Chanakyapuri | New Delhi - 110021 Tel: 011-24121764 | Fax: 011-66173415 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.vifindia.org Follow us on Twitter | @vifindia Facebook | /vifindia All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher Dr. K. Warikoo is former Professor, Centre for Inner Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He is currently Senior Fellow, Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi. This paper is based on the author’s writings published earlier, which have been updated and consolidated at one place. All photos have been taken by the author during his field studies in the region. Siberia and India: Historical Cultural Affinities India and Eurasia have had close social and cultural linkages, as Buddhism spread from India to Central Asia, Mongolia, Buryatia, Tuva and far wide. Buddhism provides a direct link between India and the peoples of Siberia (Buryatia, Chita, Irkutsk, Tuva, Altai, Urals etc.) who have distinctive historico-cultural affinities with the Indian Himalayas particularly due to common traditions and Buddhist culture. Revival of Buddhism in Siberia is of great importance to India in terms of restoring and reinvigorating the lost linkages. The Eurasianism of Russia, which is a Eurasian country due to its geographical situation, brings it closer to India in historical-cultural, political and economic terms. -

Russian Government Continues to Support Cattle Sector

THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Voluntary - Public Date: 6/17/2013 GAIN Report Number: RS1335 Russian Federation Post: Moscow Russian Government Continues to Support Cattle Sector Report Categories: Livestock and Products Policy and Program Announcements Agricultural Situation Approved By: Holly Higgins Prepared By: FAS/Moscow Staff Report Highlights: Russia’s live animal imports have soared in recent years, as the Federal Government has supported the rebuilding of the beef and cattle sector in Russia. This sector had been in continual decline since the break-up of the Soviet Union, but imports of breeding stock have resulted in a number of modern ranches. The Russian Federal and oblast governments offer a series of support programs meant to stimulate livestock development in the Russian Federation over the next seven years which are funded at hundreds of billions of Russian rubles (almost $10 billion). These programs are expected to lead to a recovery of the cattle industry. Monies have been allocated for both new construction and modernization of old livestock farms, purchase of domestic and imported of high quality breeding dairy and beef cattle, semen and embryos; all of which should have a direct and favorable impact on livestock genetic exports to Russia through 2020. General Information: Trade Russia’s live animal imports have soared in recent years, as the Federal Government has supported the rebuilding of the beef and cattle sector in Russia. This sector has been in decline since the break-up of the Soviet Union, but imports of breeding stock have resulted in a number of modern ranches which are expected to lead to a recovery of the cattle industry. -

Stephanie Hampton Et Al. “Sixty Years of Environmental Change in the World’S Deepest Freshwater Lake—Lake Baikal, Siberia,” Global Change Biology, August 2008

LTEU 153GS —Environmental Studies in Russia: Lake Baikal Lake Baikal in Siberia, Russia is approximately 25 million years old, the deepest and oldest lake in the world, holding more than 20% of earth’s fresh water, and providing a home to 2500 animal species and 1000 plant species. It is at risk of being irreparably harmed due to increasing and varied pollution and climate change. It has a rich history and culture for Russians and the many indigenous cultures surrounding it. It is the subject of social activism and public policy debate. Our course will explore the physical and biological characteristics of Lake Baikal, the risks to its survival, and the changes already observed in the ecosystem. We will also explore its cultural significance in the arts, literature, and religion, as well as political, historical, and economic issues related to it. Class will be run largely as a seminar. Each student will be expected to contribute based on their own expertise, life experience, and active learning. As a final project, student groups will draw on their own research and personal experiences with Lake Baikal to form policy proposals and a media campaign supporting them. Week 1: Biology and Geology of Lake Baikal Moscow: Meet with Environmental Group, Visit Zaryadye Park (Urban Development) Irkutsk Local Field Trip: Baikal Limnological Museum—forms of life in and around Lake Baikal Week 2: Threats to the Baikal Environment Local Field Trip: Irkutsk Dump, Baikal Interactive Center/Service Work Traveling Field Trip: Balagansk/Angara River, Anthropogenic Effects on Environment Weeks 3/4: Economics and Politics of Lake Baikal, Lake Baikal in Literature and Culture Traveling Field Trip: Olkhon Island/Service Project, Service Work on Great Baikal Trail/Camping Week 5: Comparison of Environmental Issues and Policies in Russian Urban Centers St.