Identity and Self-Determination: the Fertit Opposition in South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN

COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State SOUTH SUDAN Bureau for Community Security South Sudan Peace and Small Arms Control and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme The Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control under the Ministry of Interior is the Gov- ernment agency of South Sudan mandated to address the threats posed by the proliferation of small arms and community insecurity to peace and development. The South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission is mandated to promote peaceful co-existence amongst the people of South Sudan and advise the Government on matters related to peace. The United Nations Development Programme in South Sudan, through the Community Security and Arms Control Project supports the Bureau strengthen its capacity in the area of community security and arms control at the national, state, and county levels. Cover photo: © UNDP/Sun-Ra Lambert Baj COMMUNITY CONSULTATION REPORT Warrap State South Sudan Published by South Sudan Bureau for Community Security and Small Arms Control South Sudan Peace and Reconciliation Commission United Nations Development Programme MAY 2012 JUBA, SOUTH SUDAN CONTENTS Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... i Foreword ........................................................................................................................... .ii Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... -

An Article on Explosion of Ethnic Violence in Warrap State in South Sudan

South American Journal of Academic Research Special Edition May 2016 An article on explosion of ethnic violence in Warrap state In south Sudan Article by Emmanuel Moju, MSC on clinical psychology, Texila American University, South Sudan Email: [email protected] Abstract As matter of facts, ethnic conflict is an outcome of number of interrelated factors. It is important to cautiously and thoroughly study each of these factors and establish relationship among the characteristics involved. Appropriate approach is useful in an endeavor to resolve ethnic conflicts through a peaceful means. Ethnic conflict leads, among other things, to the breakdown of law and order, the disruption of economic activities, political stability, humanitarian crises and a state of uncertainty which prevent long run investment and development efforts and peace. A case on line is the conflict that broke out between the SPLA and SPLA in opposition on 15th December 2013, in South Sudan, all the developments made from independence till the date were gone. Violent ethnic conflict leads to extraordinary displacement of people including vulnerable groups such as women, children, the elderly as well as the disabled who often are seriously affected by violent conflict. Therefore, it is worthwhile to give due concern to interethnic relations and manage it cautiously and systematically. Conflict is like contagious disease. Unwise handling of conflict gives it the opportunity to widespread all of a sudden. If it occurred, conflict must be handled at its early stages. Once allowed to escalate, it would change to violence that cannot be easily remedied and control. A good example is the Central Africa Republic ongoing ethnic violence between the Muslims and the Christians (Alemayehu, Fantaw. -

EOI Mission Template

United Nations Nations Unies United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) South Sudan REQUEST FOR EXPRESSION OF INTEREST (EOI) This notice is placed on behalf of UNMISS. United Nations Procurement Division (UNPD) cannot provide any warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of contents of furnished information; and is unable to answer any enquiries regarding this EOI. You are therefore requested to direct all your queries to United Nation Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) using the fax number or e-mail address provided below. Title of the EOI: Provision of Refrigerant Gases to UNMISS in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan Date of this EOI: 10 January 2020 Closing Date for Receipt of EOI: 11 February 2020 EOI Number: EOIUNMISS17098 Chief Procurement Officer Unmiss Hq, Tomping Site Near Juba Address EOI response by fax or e-mail to the Attention of: International Airport, Room No 3c/02 Juba, Republic Of South Sudan Fax Number: N/A E-mail Address: [email protected], [email protected] UNSPSC Code: 24131513 DESCRIPTION OF REQUIREMENTS PD/EOI/MISSION v2018-01 1. The United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (UNMISS) has a requirement for the provision of Refrigerant Gases in Juba, Bor, Bentiu, Malakal, Wau, Kuajok, Rumbek, Aweil, Torit and Yambio, Republic of South Sudan and hereby solicits Expression of Interest (EOI) from qualified and interested vendors. SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS / INFORMATION (IF ANY) Conditions: 2. Interested service providers/companies are invited to submit their EOIs for consideration by email (preferred), courier or by hand delivery as indicated below. -

Republic of South Sudan "Establishment Order

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN "ESTABLISHMENT ORDER NUMBER 36/2015 FOR THE CREATION OF 28 STATES" IN THE DECENTRALIZED GOVERNANCE SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN Order 1 Preliminary Citation, commencement and interpretation 1. This order shall be cited as "the Establishment Order number 36/2015 AD" for the creation of new South Sudan states. 2. The Establishment Order shall come into force in thirty (30) working days from the date of signature by the President of the Republic. 3. Interpretation as per this Order: 3.1. "Establishment Order", means this Republican Order number 36/2015 AD under which the states of South Sudan are created. 3.2. "President" means the President of the Republic of South Sudan 3.3. "States" means the 28 states in the decentralized South Sudan as per the attached Map herewith which are established by this Order. 3.4. "Governor" means a governor of a state, for the time being, who shall be appointed by the President of the Republic until the permanent constitution is promulgated and elections are conducted. 3.5. "State constitution", means constitution of each state promulgated by an appointed state legislative assembly which shall conform to the Transitional Constitution of South Sudan 2011, amended 2015 until the permanent Constitution is promulgated under which the state constitutions shall conform to. 3.6. "State Legislative Assembly", means a legislative body, which for the time being, shall be appointed by the President and the same shall constitute itself into transitional state legislative assembly in the first sitting presided over by the most eldest person amongst the members and elect its speaker and deputy speaker among its members. -

Communities Tackling Small Arms and Light Weapons in South Sudan Briefing

Briefing July 2018 Communities tackling small arms and light weapons in South Sudan Lessons learnt and best practices Introduction The proliferation and misuse of small arms and light Clumsy attempts at forced disarmament have created fear weapons (SALW) is one of the most pervasive problems and resentment in communities. In many cases, arms end facing South Sudan, and one which it has been struggling up recirculating afterwards. This occurs for two reasons: to reverse since before independence in July 2011. firstly, those carrying out enforced disarmaments are – either deliberately or through negligence – allowing Although remoteness and insecurity has meant that seized weapons to re-enter the illicit market. Secondly, extensive research into the exact number of SALW in there have been no simultaneous attempts to address the circulation in South Sudan is not possible, assessments of demand for SALW within the civilian population. While the prevalence of illicit arms are alarming. conflict and insecurity persists, demand for SALW is likely to remain. Based on a survey conducted in government controlled areas only, the Small Arms Survey estimated that between In April 2017, Saferworld, with support from United 232,000–601,000 illicit arms were in circulation in South Nations Mine Action Service (UNMAS), launched a project Sudan in 20161. It is estimated that numbers of SALW are to identify and improve community-based solutions likely to be higher in rebel-held areas. to the threats posed by the proliferation and misuse of SALW. The one-year pilot project aimed to raise Estimates also vary from state to state within South awareness among communities about the dangers of Sudan. -

Strategic Peacebuilding- the Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan

SPECIAL REPORT Strategic Peacebuilding The Role of Civilians and Civil Society in Preventing Mass Atrocities in South Sudan The Cases of the SPLM Leadership Crisis (2013), the Military Standoff at General Malong’s House (2017), and the Wau Crisis (2016–17) NYATHON H. MAI JULY 2020 WEEKLY REVIEW June 7, 2020 The Boiling Frustrations in South Sudan Abraham A. Awolich outh Sudan’s 2018 peace agreement that ended the deadly 6-year civil war is in jeopardy, both because the parties to it are back to brinkmanship over a number S of mildly contentious issues in the agreement and because the implementation process has skipped over fundamental st eps in a rush to form a unity government. It seems that the parties, the mediators and guarantors of the agreement wereof the mind that a quick formation of the Revitalized Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) would start to build trust between the leaders and to procure a public buy-in. Unfortunately, a unity government that is devoid of capacity and political will is unable to address the fundamentals of peace, namely, security, basic services, and justice and accountability. The result is that the citizens at all levels of society are disappointed in RTGoNU, with many taking the law, order, security, and survival into their own hands due to the ubiquitous absence of government in their everyday lives. The country is now at more risk of becoming undone at its seams than any other time since the liberation war ended in 2005. The current st ate of affairs in the country has been long in the making. -

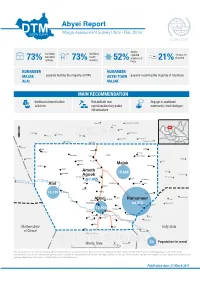

20170331 Abyei

Abyei Report Village Assessment Survey | Nov - Dec 2016 IOM OIM bomas functional functional reported villages are 73% education 73% health 52% presence of 21% deserted facilities facilities UXOs. RUMAMEER RUMAMEER MAJAK payams hosting the majority of IDPs ABYEI TOWN payams receiving the majority of returnees ALAL MAJAK MAIN SURVEY RECOMMENDATIONS MAIN RECOMMENDATION livelihood diversication Rehabilitate and Engage in sustained activities operationalize key public community-level dialogue infrastructure Ed Dibeikir Ramthil Raqabat Rumaylah Nyam Roba Nabek Umm Biura El Amma Mekeines Zerafat SUDABeida N Ed Dabkir Shagawah Duhul Kawak Al Agad Al Aza Meiram Tajiel Dabib Farouk Debab Pariang Um Khaer Langar Di@ra Raqaba Kokai Es Saart El Halluf Pagol Bioknom Pandal Ajaj Kajjam Majak Ghabush En Nimr Shigei Di@ra Ameth Nyak Kolading 15,685 Gumriak 2 Aguok Goli Ed Dahlob En Neggu Fagai 1,055 Dumboloya Nugar As Sumayh Alal Alal Um Khariet Bedheni Baar Todach Saheib Et Timsah Noong 13,130 Ed Derangis Tejalei Feid El Kok Dungoup Padit DokurAbyeia Rumameer Todyop Madingthon 68,372 Abu Qurun Thurpader Hamir Leu 12,900 Awoluum Agany Toak Banton Athony Marial Achak Galadu Arik Athony Grinঞ Agach Awal Aweragor Madul Northern Bahr Agok Unity State Lort Dal el Ghazal Abiemnom Baralil Marsh XX Population in need SOUTH SUDANMolbang Warrap State Ajakuao 0 25 50 km The boundaries on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the Government of the Republic of South Sudan or IOM. This map is for planning purposes only. IOM cannot guarantee this map is error free and therefore accepts no liability for consequential and indirect damages arising from its use. -

South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’S Newest Country

The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Ted Dagne Specialist in African Affairs July 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41900 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Republic of South Sudan: Opportunities and Challenges for Africa’s Newest Country Summary In January 2011, South Sudan held a referendum to decide between unity or independence from the central government of Sudan as called for by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement that ended the country’s decades-long civil war in 2005. According to the South Sudan Referendum Commission (SSRC), 98.8% of the votes cast were in favor of separation. In February 2011, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir officially accepted the referendum result, as did the United Nations, the African Union, the European Union, the United States, and other countries. On July 9, 2011, South Sudan is to officially declare its independence. The Obama Administration welcomed the outcome of the referendum and pledged to recognize South Sudan as an independent country in July 2011. The Administration is expected to send a high-level presidential delegation to South Sudan’s independence celebration on July 9, 2011. A new ambassador is also expected to be named to South Sudan. South Sudan faces a number of challenges in the coming years. Relations between Juba, in South Sudan, and Khartoum are poor, and there are a number of unresolved issues between them. The crisis in the disputed area of Abyei remains a contentious issue, despite a temporary agreement reached in mid-June 2011. -

Addis PEACE a 411St ME HEADS O BANJUL, 30 DECEM AFRICAN

AFRICAN UNION UNION AFRICAINE UNIÃO AFRICANA Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, P.O. Box: 3243 Tel.: (251‐11) 5513 822 Fax: (251‐11) 5519 321 Email: situationroom@africa‐union.org PEACE AND SECURITY COUNCIL 411st MEETING AT THE LEVEL OF HEADS OF STATE AND GOVERNMENT BANJUL, THE GAMBIA 30 DECEMBER 2013 PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OFF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN PSC/AHG/3(CDXI) Page 1 REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON OF THE COMMISSION ON THE SITUATION IN SOUTH SUDAN I. INTRODUCTION 1. The present report is submitted in the context of the meeting of Council to be held in Banjul, The Gambia, on 30 December 2013, to deliberate on the unfolding situation in South Sudan. The conflict in South Sudan erupted on 15 December, in the context of a political challenge to the President of the Republic of South Sudan, from leading members of the ruling party, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). This rapidly mutated into violent confrontation and rebellion. The conflict imperils the lives and wellbeing of South Sudanese, jeopardizes the future of the young nation, and is a threat to regional peace and security. 2. The report provides a background to the current crisis, a chronology of the events of the last six months and an overview of the regional, continental and international response. The report concludes with observations on the way forward. II. BACKGROUND 3. The current conflict represents the accumulation of unresolved political disputes within the leadership of the SPLM. The leaders had disagreements on fundamental aspects of the party and country’s leadership, governance and direction. -

Partner Presence and Interventions in Warrap State A14062012-1

FSL Cluster Partner Presence and Interventions in Warrap State A14062012-1 27°0'0"E 30°0'0"E Disclaimer The boundaries and and names shown and the designations used on this map do not Abyei imply offical endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations or the Government U of South Sudan. For any comment please contact: F S L - c l u st e r- s s d @ fa o . o r g n it Data sources y H! * Administrative boundaries were obtained courtesy of IMU OCHA; State capitals * Kind of interventions are provided by FSL Cluster partners ! H Undetermined boundary 13 Bentiu Twic Primary roads N N " " 0 0 ' Secondary roads ' 0 0 ° ° 9 l 9 za ha Gogrial East Tertiary roads l G r e ah Rivers B ern H! rth Abyei administrative area No Aweil t s International boundary e 6 11 Warrap W l South Sudan states a i 8 r g South Sudan counties J o o G n Waterbg ody/marsh l H! Tonj North e Kuajok Grazingi areas Type of intervention Food assistance and livestock interventions Tonj East Food assistance, livestock, income & employment, value addition/markets, and Intervening Partners' by County H! 5 agriculture interventions County Livestock Gogrial East FAO, VSF Suisse Wau Gogrial West FAO, VSF Suisse * Figures indicate number of partners Tonj East VSF Belgium, FAO, VSF Suisse Tonj North VSF Belgium, FAO, VSF Suisse Tonj South FAO, VSF Suisse Scale 1: 665,360 Twic FAO, VSF Suisse 7 Map Paper Size: A1 ¬ Map created: June 2012 County Income/Employment Value Addition/Markets Gogrial East FAO, VSF Germany VSF Germany Gogrial West NRC, FAO, NPA FAO Sudan Tonj East Tonj South -

Secretary-General's Report on South Sudan (September 2020)

United Nations S/2020/890 Security Council Distr.: General 8 September 2020 Original: English Situation in South Sudan Report of the Secretary-General I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 2514 (2020), by which the Council extended the mandate of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) until 15 March 2021 and requested me to report to the Council on the implementation of the Mission’s mandate every 90 days. It covers political and security developments between 1 June and 31 August 2020, the humanitarian and human rights situation and progress made in the implementation of the Mission’s mandate. II. Political and economic developments 2. On 17 June, the President of South Sudan, Salva Kiir, and the First Vice- President, Riek Machar, reached a decision on responsibility-sharing ratios for gubernatorial and State positions, ending a three-month impasse on the allocations of States. Central Equatoria, Eastern Equatoria, Lakes, Northern Bahr el-Ghazal, Warrap and Unity were allocated to the incumbent Transitional Government of National Unity; Upper Nile, Western Bahr el-Ghazal and Western Equatoria were allocated to the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army in Opposition (SPLM/A-IO); and Jonglei was allocated to the South Sudan Opposition Alliance. The Other Political Parties coalition was not allocated a State, as envisioned in the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan, in which the coalition had been guaranteed 8 per cent of the positions. 3. On 29 June, the President appointed governors of 8 of the 10 States and chief administrators of the administrative areas of Abyei, Ruweng and Pibor. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM Via Free Access “They Are Now Community Police” 411

international journal on minority and group rights 22 (2015) 410-434 brill.com/ijgr “They Are Now Community Police”: Negotiating the Boundaries and Nature of the Government in South Sudan through the Identity of Militarised Cattle-keepers Naomi Pendle PhD Candidate, London School of Economics, London, UK [email protected] Abstract Armed, cattle-herding men in Africa are often assumed to be at a relational and spatial distance from the ‘legitimate’ armed forces of the government. The vision constructed of the South Sudanese government in 2005 by the Comprehensive Peace Agreement removed legitimacy from non-government armed groups including localised, armed, defence forces that protected communities and cattle. Yet, militarised cattle-herding men of South Sudan have had various relationships with the governing Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army over the last thirty years, blurring the government – non government boundary. With tens of thousands killed since December 2013 in South Sudan, questions are being asked about options for justice especially for governing elites. A contextual understanding of the armed forces and their relationship to gov- ernment over time is needed to understand the genesis and apparent legitimacy of this violence. Keywords South Sudan – policing – vigilantism – transitional justice – war crimes – security © NAOMI PENDLE, 2015 | doi 10.1163/15718115-02203006 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 (CC-BY-NC 4.0) License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/Downloaded from Brill.com09/24/2021 04:59:59AM via free access “they Are Now Community Police” 411 1 Introduction1 On 15 December 2013, violence erupted in Juba, South Sudan among Nuer sol- diers of the Presidential Guard.