Grouse and Quails of North America — Frontmatter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

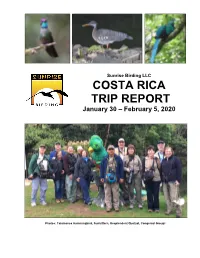

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Sage-Grouse Hunting Season

CHAPTER 11 UPLAND GAME BIRD AND SMALL GAME HUNTING SEASONS Section 1. Authority. This regulation is promulgated by authority of Wyoming Statutes § 23-1-302 and § 23-2-105 (d). Section 2. Hunting Regulations. (a) Bag and Possession Limit. Only one (1) daily bag limit of each species of upland game birds and small game may be taken per day regardless of the number of hunt areas hunted in a single day. When hunting more than one (1) hunt area, a person’s daily and possession limits shall be equal to, but shall not exceed, the largest daily and possession limit prescribed for any one (1) of the specified hunt areas in which the hunting and possession occurs. (b) Evidence of sex and species shall remain naturally attached to the carcass of any upland game bird in the field and during transportation. For pheasant, this shall include the feathered head, feathered wing or foot. For all other upland game bird species, this shall include one fully feathered wing. (c) No person shall possess or use shot other than nontoxic shot for hunting game birds and small game with a shotgun on the Commission’s Table Mountain and Springer wildlife habitat management areas and on all national wildlife refuges open for hunting. (d) Required Clothing. Any person hunting pheasants within the boundaries of any Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Wildlife Habitat Management Area, or on Bureau of Reclamation Withdrawal lands bordering and including Glendo State Park, shall wear in a visible manner at least one (1) outer garment of fluorescent orange or fluorescent pink color which shall include a hat, shirt, jacket, coat, vest or sweater. -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

Wild Turkey Education Guide

Table of Contents Section 1: Eastern Wild Turkey Ecology 1. Eastern Wild Turkey Quick Facts………………………………………………...pg 2 2. Eastern Wild Turkey Fact Sheet………………………………………………….pg 4 3. Wild Turkey Lifecycle……………………………………………………………..pg 8 4. Eastern Wild Turkey Adaptations ………………………………………………pg 9 Section 2: Eastern Wild Turkey Management 1. Wild Turkey Management Timeline…………………….……………………….pg 18 2. History of Wild Turkey Management …………………...…..…………………..pg 19 3. Modern Wild Turkey Management in Maryland………...……………………..pg 22 4. Managing Wild Turkeys Today ……………………………………………….....pg 25 Section 3: Activity Lesson Plans 1. Activity: Growing Up WILD: Tasty Turkeys (Grades K-2)……………..….…..pg 33 2. Activity: Calling All Turkeys (Grades K-5)………………………………..…….pg 37 3. Activity: Fit for a Turkey (Grades 3-5)…………………………………………...pg 40 4. Activity: Project WILD adaptation: Too Many Turkeys (Grades K-5)…..…….pg 43 5. Activity: Project WILD: Quick, Frozen Critters (Grades 5-8).……………….…pg 47 6. Activity: Project WILD: Turkey Trouble (Grades 9-12………………….……....pg 51 7. Activity: Project WILD: Let’s Talk Turkey (Grades 9-12)..……………..………pg 58 Section 4: Additional Activities: 1. Wild Turkey Ecology Word Find………………………………………….…….pg 66 2. Wild Turkey Management Word Find………………………………………….pg 68 3. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 70 4. Turkey Coloring Sheet ..………………………………………………………….pg 71 5. Turkey Color-by-Letter……………………………………..…………………….pg 72 6. Five Little Turkeys Song Sheet……. ………………………………………….…pg 73 7. Thankful Turkey…………………..…………………………………………….....pg 74 8. Graph-a-Turkey………………………………….…………………………….…..pg 75 9. Turkey Trouble Maze…………………………………………………………..….pg 76 10. What Animals Made These Tracks………………………………………….……pg 78 11. Drinking Straw Turkey Call Craft……………………………………….….……pg 80 Section 5: Wild Turkey PowerPoint Slide Notes The facilities and services of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources are available to all without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, age, national origin or physical or mental disability. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Evaluation of Northern Bobwhite and Scaled Quail in Western Oklahoma

P-1054 Research Summary: Evaluation of Northern Bobwhite and Scaled Quail in Western Oklahoma Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources Oklahoma State University Research Summary: Evaluation of Northern Bobwhite and Scaled Quail in Western Oklahoma Researchers involved in this study included: Kent Andersson Senior Research Specialist Eric Thacker Post-Doctoral Researcher Matt Carroll, PhD Evan Tanner, PhD Jeremy Orange, MS Rachel Carroll, MS Cameron Duquette, MS Craig Davis Professor and Bollenbach Chair in Wildlife Management Sam Fuhlendorf Professor and Groendyke Chair in Wildlife Conservation Dwayne Elmore Extension Wildlife Specialist, Professor and Bollenbach Chair in Wildlife Management Introduction Results and Implications There are two species of native quail that occur Survival in Oklahoma, the northern bobwhite (hereafter bobwhite), and the scaled quail (or blue quail). During the study, 1,051 mortalities were Both of these species are popular with hunters and recorded at Packsaddle Wildlife Management landowners. Due to a concern about declining Area. Forty-four percent were attributed to quail populations in the state, a cooperative quail mammals, 33 percent to raptors, 9 percent to study between Oklahoma State University and the hunter harvest, 5 percent to unknown predation, Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation 3 percent to weather exposure and 7 percent to was conducted on the Packsaddle and Beaver miscellaneous causes. River Wildlife Management Areas from 2011- At Beaver River Wildlife Management Area, 2017. Broadly, the project was intended to 929 mortalities were recorded. Forty-seven document survival, nest success, brood success, percent were attributed to mammals, 27 percent habitat selection, genetics and movement of quail. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

Hunting Regulations

WYOMING GAME AND FISH COMMISSION Upland Game Bird, Small Game, Migratory 2021 Game Bird and Wild Turkey Hunting Regulations Conservation Stamp Price Increase Effective July 1, 2021, the price for a 12-month conservation stamp is $21.50. A conservation stamp purchased on or before June 30, 2021 will be valid for 12 months from the date of purchase as indicated on the stamp. (See page 5) wgfd.wyo.gov Wyoming Hunting Regulations | 1 CONTENTS GENERAL 2021 License/Permit/Stamp Fees Access Yes Program ................................................................... 4 Carcass Coupons Dating and Display.................................... 4, 29 Pheasant Special Management Permit ............................................$15.50 Terms and Definitions .................................................................5 Resident Daily Game Bird/Small Game ............................................. $9.00 Department Contact Information ................................................ 3 Nonresident Daily Game Bird/Small Game .......................................$22.00 Important Hunting Information ................................................... 4 Resident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ...................................... $27.00 License/Permit/Stamp Fees ........................................................ 2 Nonresident 12 Month Game Bird/Small Game ..................................$74.00 Stop Poaching Program .............................................................. 2 Nonresident 12 Month Youth Game Bird/Small Game Wild Turkey -

Ruffed Grouse

Ruffed Grouse Photo Courtesy of the Ruffed Grouse Society Introduction The ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) is North America’s most widely distributed game bird. As a very popular game species, the grouse is in the same family as the wild turkey, quail and pheasant. They range from Alaska to Georgia including 34 states and all the Canadian provinces. Historically in Indiana, its range included the forested regions of the state. Today the range is limited to the south central and southeastern 1/3 of the state in the southern hill country, with a few pockets in counties bordering Michigan. Ruffed grouse weigh between 1 and 1.5 pounds and grow to 17 inches in length with a 22-inch wingspan. They exhibit color phases with northern range birds being reddish-brown to gray while those in the southern part of their continental range, including Indiana, are red. History and Current Status Before settlement, grouse populations ranged throughout the hardwood region of the state. In areas where timber was permanently removed for farms, homes and towns grouse habitat has been lost. During the early1900’s, many farms in the south-central portion of Indiana were abandoned. As a result of this farm abandonment, the vegetation around old home sites and in the fallow fields grew through early plant succession stages. About the same time, the reforestation era began as abandoned farms reverted into public ownership under the management of state and federal natural resource agencies. By the 1950’s, natural succession, reforestation, and timber harvest management were beginning to form a myriad of early successional forest patches across a fairly contiguous forested landscape. -

2005-06 New Jersey Firearm Hunter Survey

2005-06 NJ Firearm Hunter Harvest, Recreational and Economic Survey Summary Mail questionnaires were sent to 4,438 firearm hunters licensed during the 2004 calendar year (5.8 percent of all firearm license sales) requesting harvest, recreational and economic information for the 2005-06 hunting season. Survey results indicate that firearm hunters are aging and that retention of younger hunters is low. The mean age of licensed firearm hunters sampled is 44.3 ± 0.4 years of age. Resident firearm hunters live in every county of the state, and 79.8 percent of non-resident firearm hunters reside in the neighboring states of Pennsylvania, New York and Delaware. Firearm license sales (72,604 in 2005) have declined to their lowest point since 1914. Nearly one-half of survey respondents actively pursued at least one of the 14 small game species open to hunting. An estimated 35,411 small game firearm hunters spent in excess of 11.1 million dollars (US, excluding license, permit and stamp fees), enjoyed 420,228 recreation-days and harvested an estimated 61,811 northern bobwhite, 6,481 crows, 27,546 chukar partridge, 711 ruffed grouse, 155,238 pheasants, 3,794 woodcock, 198 eastern coyotes, 79 gray fox, 18,140 gray squirrels, 30,431 rabbits and hares, 435 raccoons, 790 red fox and 4,031 woodchucks during the 2005-06 season. This survey was conducted as part of Job III-B. Hunter and Trapper Harvest, Recreational and Economic Survey. This job is included within Grant Number W-68-R-8, New Jersey Wildlife Research and Management: Project III. -

Upland Game Management Plan 2019-2025

Idaho Upland Game Management Plan 2019-2025 Prepared by IDAHO DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME July 2019 Recommended Citation: Idaho Department of Fish and Game. 2019. Idaho upland game management plan, 2019-2025. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Boise, USA. Front and Back Cover Photographs: Front Cover: Ruffed Grouse ©Agnieszka Bacal CC YB -NC-ND 2.0, Shutterstock Back Cover: ©Glenn Oakley Additional copies: Additional copies can be downloaded from the Idaho Department of Fish and Game website at idfg.idaho.gov Idaho Department of Fish and Game – Upland Game Planning Team: Tyler Archibald – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Regan Berkley – Regional Wildlife Manager, Southwest Region (McCall) Rachel Curtis – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southwest Region Don Jenkins – Regional Habitat Manager, Clearwater Region Jeffrey Knetter – Team Leader and Wildlife Program Coordinator, Headquarters Joe Kozfkay – State Fisheries Manager, Headquarters David Leptich – Regional Wildlife Biologist, Panhandle Region Mike McDonald - Regional Wildlife Manager, Magic Valley Region Ann Moser – Wildlife Staff Biologist, Headquarters Greg Painter - Regional Wildlife Manager, Salmon Region Sal Palazzolo - Wildlife Program Coordinator, Headquarters Maria Pacioretty - Regional Wildlife Biologist, Southeast Region Matt Proett - Regional Wildlife Biologist, Upper Snake Region Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) adheres to all applicable state and federal laws and regulations related to discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, gender, disability or veteran’s status. If you feel you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility of IDFG, or if you desire further information, please write to: Idaho Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 25, Boise, ID 83707 or U.S. -

Winter Food of Oklahoma Quail* by Lois Gould Bird and R

Winter Food of Oklahoma Quail 293 WINTER FOOD OF OKLAHOMA QUAIL* BY LOIS GOULD BIRD AND R. D. BIRD This study is based upon an examination of the crops of 138 quail taken in nineteen counties of Oklahoma. Of these, 135 were taken in December, 1929, during the latter part of the quail season and were sent to us by the state game rangers in response to a request made to Mr. Marsh B. Woodruff, then Assistant Game Warden. Three crops were taken in November by R. D. Bird. With the exception of four crops from Arizona Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata pallida) from Cimmarron County, they were all from Bob-white (Colinus virginianus virginianus). The study of the winter food of birds is important because winter is the critical time of food gathering. It is then that food is scarcest. Food taken from bird crops is easily studied, for the contents have not been subjected to the process of digestion and are not affected by chemical action. The crop is a membranous, sac-like region of the oesophagus, easily distensible, which is used for the reception of food. Its capacity is from four to six times that of the gizzard. (2, p. 28). Seeds and insects in the crop, although in some cases broken and dirty, are in practically the same condition as when lying on the ground. PREVIOUS WORK Dr. Sylvester D. Judd, of the United States Biological Survey, who has made extensive studies of the food of the Bob-white, states: “The Bob-white is probably the most useful abundant species on the farm.