Introduction: on Writing the History of Early English Criticism 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

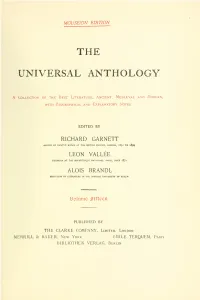

The Universal Anthology

MOUSEION EDITION THE UNIVERSAL ANTHOLOGY A Collection of the Best Literature, Ancient, Medieval and Modern, WITH Biographical and Explanatory Notes EDITED BY RICHARD GARNETT KEEPER OF PRINTED BOOKS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM, LONDON, 185I TO 1899 LEON VALLEE LIBRARIAN AT THE BIBLIOTHEQJJE NATIONALE, PARIS, SINCE I87I ALOIS BRANDL PKOFESSOR OF LITERATURE IN THE IMPERIAL UNIVERSITY OP BERLIN IDoluine ififteen PUBLISHED BY THE CLARKE COMPANY, Limited, London MERRILL & BAKER. New York EMILE TERQUEM. Paris BIBLIOTHEK VERLAG, Berlin Entered at Stationers' Hall London, 1899 Droits de reproduction et da traduction reserve Paris, 1899 Alle rechte, insbesondere das der Ubersetzung, vorbehalten Berlin, 1899 Proprieta Letieraria, Riservate tutti i divitti Rome, 1899 Copyright 1899 by Richard Garnett IMMORALITY OF THE ENGLISH STAGE. 347 Young Fashion — Hell and Furies, is this to be borne ? Lory — Faith, sir, I cou'd almost have given him a knock o' th' pate myself. A Shoet View of the IMMORALITY AND PROFANENESS OF THE ENG- LISH STAGE. By JEREMY COLLIER. [Jeremy Collier, reformer, was bom in Cambridgeshire, England, in 1650. He was educated at Cambridge, became a clergyman, and was a " nonjuror" after the Revolution ; not only refusing the oath, but twice imprisoned, once for a pamphlet denying that James had abdicated, and once for treasonable corre- spondence. In 1696 he was outlawed for absolving on the scaffold two conspira- tors hanged for attempting William's life ; and though he returned later and lived unmolested in London, the sentence was never rescinded. Besides polemics and moral essays, he wrote a cyclopedia and an " Ecclesiastical IILstory of Great Britain," and translated Moreri's Dictionary. -

Essay by Julian Pooley; University of Leicester, John Nichols and His

'A Copious Collection of Newspapers' John Nichols and his Collection of Newspapers, Pamphlets and News Sheets, 1760–1865 Julian Pooley, University of Leicester Introduction John Nichols (1745–1826) was a leading London printer who inherited the business of his former master and partner, William Bowyer the Younger, in 1777, and rose to be Master of the Stationers’ Company in 1804.1 He was also a prominent literary biographer and antiquary whose publications, including biographies of Hogarth and Swift, and a county history of Leicestershire, continue to inform and inspire scholarship today.2 Much of his research drew upon his vast collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century newspapers. This essay, based on my ongoing work on the surviving papers of the Nichols family, will trace the history of John Nichols’ newspaper collection. It will show how he acquired his newspapers, explore their influence upon his research and discuss the changing fortunes of his collection prior to its acquisition by the Bodleian Library in 1865. 1 For useful biographical studies of John Nichols, see Albert H. Smith, ‘John Nichols, Printer and 2 The first edition of John Nichols’ Anecdotes of Mr Hogarth (London, 1780) grew, with the assistance Publisher’ The Library Fifth Series 18.3 (September 1963), pp. 169–190; James M. Kuist, The Works of Isaac Reed and George Steevens, into The Works of William Hogarth from the Original Plates of John Nichols. An Introduction (New York, 1968), Alan Broadfield, ‘John Nichols as Historian restored by James Heath RA to which is prefixed a biographical essay on the genius and productions of and Friend. -

I the POLITICS of DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS

THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 by Loring Pfeiffer B. A., Swarthmore College, 2002 M. A., University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2015 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Loring Pfeiffer It was defended on May 1, 2015 and approved by Kristina Straub, Professor, English, Carnegie Mellon University John Twyning, Professor, English, and Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies, Courtney Weikle-Mills, Associate Professor, English Dissertation Advisor: Jennifer Waldron, Associate Professor, English ii Copyright © by Loring Pfeiffer 2015 iii THE POLITICS OF DESIRE: ENGLISH WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS, PARTISANSHIP, AND THE STAGING OF FEMALE SEXUALITY, 1660-1737 Loring Pfeiffer, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 The Politics of Desire argues that late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century women playwrights make key interventions into period politics through comedic representations of sexualized female characters. During the Restoration and the early eighteenth century in England, partisan goings-on were repeatedly refracted through the prism of female sexuality. Charles II asserted his right to the throne by hanging portraits of his courtesans at Whitehall, while Whigs avoided blame for the volatility of the early eighteenth-century stock market by foisting fault for financial instability onto female gamblers. The discourses of sexuality and politics were imbricated in the texts of this period; however, scholars have not fully appreciated how female dramatists’ treatment of desiring female characters reflects their partisan investments. -

Jane Milling

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE ‘“For Without Vanity I’m Better Known”: Restoration Actors and Metatheatre on the London Stage.’ AUTHORS Milling, Jane JOURNAL Theatre Survey DEPOSITED IN ORE 18 March 2013 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/4491 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Theatre Survey 52:1 (May 2011) # American Society for Theatre Research 2011 doi:10.1017/S0040557411000068 Jane Milling “FOR WITHOUT VANITY,I’M BETTER KNOWN”: RESTORATION ACTORS AND METATHEATRE ON THE LONDON STAGE Prologue, To the Duke of Lerma, Spoken by Mrs. Ellen[Nell], and Mrs. Nepp. NEPP: How, Mrs. Ellen, not dress’d yet, and all the Play ready to begin? EL[LEN]: Not so near ready to begin as you think for. NEPP: Why, what’s the matter? ELLEN: The Poet, and the Company are wrangling within. NEPP: About what? ELLEN: A prologue. NEPP: Why, Is’t an ill one? NELL[ELLEN]: Two to one, but it had been so if he had writ any; but the Conscious Poet with much modesty, and very Civilly and Sillily—has writ none.... NEPP: What shall we do then? ’Slife let’s be bold, And speak a Prologue— NELL[ELLEN]: —No, no let us Scold.1 When Samuel Pepys heard Nell Gwyn2 and Elizabeth Knipp3 deliver the prologue to Robert Howard’s The Duke of Lerma, he recorded the experience in his diary: “Knepp and Nell spoke the prologue most excellently, especially Knepp, who spoke beyond any creature I ever heard.”4 By 20 February 1668, when Pepys noted his thoughts, he had known Knipp personally for two years, much to the chagrin of his wife. -

Pdf\Preparatory\Charles Wesley Book Catalogue Pub.Wpd

Proceedings of the Charles Wesley Society 14 (2010): 73–103. (This .pdf version reproduces pagination of printed form) Charles Wesley’s Personal Library, ca. 1765 Randy L. Maddox John Wesley made a regular practice of recording in his diary the books that he was reading, which has been a significant resource for scholars in considering influences on his thought.1 If Charles Wesley kept such diary records, they have been lost to us. However, he provides another resource among his surviving manuscript materials that helps significantly in this regard. On at least four occasions Charles compiled manuscript catalogues of books that he owned, providing a fairly complete sense of his personal library around the year 1765. Indeed, these lists give us better records for Charles Wesley’s personal library than we have for the library of brother John.2 The earliest of Charles Wesley’s catalogues is found in MS Richmond Tracts.3 While this list is undated, several of the manuscript hymns that Wesley included in the volume focus on 1746, providing a likely time that he started compiling the list. Changes in the color of ink and size of pen make clear that this was a “growing” list, with additions being made into the early 1750s. The other three catalogues are grouped together in an untitled manuscript notebook containing an assortment of financial records and other materials related to Charles Wesley and his family.4 The first of these three lists is titled “Catalogue of Books, 1 Jan 1757.”5 Like the earlier list, this date indicates when the initial entries were made; both the publication date of some books on the list and Wesley’s inscriptions in surviving volumes make clear that he continued to add to the list over the next few years. -

English Literature 1590 – 1798

UGC MHRD ePGPathshala Subject: English Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Paper 02: English Literature 1590 – 1798 Paper Coordinator: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad Module No 31: William Wycherley: The Country Wife Content writer: Ms.Maria RajanThaliath; St. Claret College; Bangalore Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee; University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Dr. Anna Kurian; University of Hyderabad William Wycherley’s The Country Wife Introduction This lesson deals with one of the most famous examples of Restoration theatre: William Wycherley’s The Country Wife, which gained a reputation in its time for being both bawdy and witty. We will begin with an introduction to the dramatist and the form and then proceed to a discussion of the play and its elements and conclude with a survey of the criticism it has garnered over the years. Section One: William Wycherley and the Comedy of Manners William Wycherley (b.1640- d.1716) is considered one of the major Restoration playwrights. He wrote at a time when the monarchy in England had just been re-established with the crowning of Charles II in 1660. The newly crowned king effected a cultural restoration by reopening the theatres which had been shut since 1642. There was a proliferation of theatres and theatre-goers. A main reason for the last was the introduction of women actors. Puritan solemnity was replaced with general levity, a characteristic of the Caroline court. Restoration Comedy exemplifies an aristocratic albeit chauvinistic lifestyle of relentless sexual intrigue and conquest. The Comedy of Manners in particular, satirizes the pretentious morality and wit of the upper classes. -

Season of 1705-1706{/Season}

Season of 1705-1706 anbrugh’s company began the autumn back at Lincoln’s Inn Fields V while they awaited completion of the theatre they had opened with a conspicuous lack of success the previous April. When the Queen’s Theatre in the Haymarket reopened on 30 October with the première of Vanbrugh’s own The Confederacy (a solid success), competition on something like an equal basis was restored to the London theatre for the first time since the union of 1682. Bitter as the theatrical competition of the late 1690s had been, it was always unequal: Rich had enjoyed two good theatre buildings but had to make do with mostly young and second-rate actors; the cooperative at Lin- coln’s Inn Fields included practically every star actor in London, but suffered from a cramped and technically inadequate theatre. By the autumn of 1705 the senior actors had become decidedly long in the tooth, but finally had a theatre capable of staging the semi-operas in which Betterton had long spe- cialized. Against them Rich had a company that had grown up: among its members were such stars as Robert Wilks, Colley Cibber, and Anne Oldfield. The failed union negotiations of summer 1705 left both managements in an ill temper, and for the first time in some years both companies made a serious effort to mount important new shows. Competition was at its hottest in the realm of opera. Under the circum- stances, this was hardly surprising: Betterton had been hankering after the glory days of Henry Purcell’s semi-operas since he was forced out of Dorset Garden in 1695; Vanbrugh was strongly predisposed toward experimenting with the new, all-sung Italianate form of opera; and Christopher Rich, having evidently made fat profits off Arsinoe the previous season, was eager for an- other such coup. -

Dryden and Johnson on Shakespeare Nicholas Hudson

Document generated on 09/26/2021 11:31 p.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle The Mystery of Aesthetic Response: Dryden and Johnson on Shakespeare Nicholas Hudson Volume 30, 2011 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1007713ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1007713ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Hudson, N. (2011). The Mystery of Aesthetic Response: Dryden and Johnson on Shakespeare. Lumen, 30, 21–31. https://doi.org/10.7202/1007713ar Copyright © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 2011 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ The Mystery of Aesthetic Response 21 2. The Mystery of Aesthetic Response: Dryden and Johnson on Shakespeare The year 1678 marked an important and formative moment in the his- tory of Shakespearian criticism. It was in the this year that John Dryden read a copy of Thomas Rymer’s The Tragedies of the Last Age, which the author had sent him. -

John Dunton's Will PRO PROB LI/657 , P. BZ

\-r John Dunton'sWill PROPROB LI/657 , p. BZ In the Name of God Amen. I John Dunton Citizen and Stationer of London and late of St Giles Cripplegate parish in the County of Middlesex being through merry of health of Body and mind Do make this my last will and Testament concerning all my Earthly pittance. For my Soul I bequeath it into the hands of Almighty God, and so hope through the meritts of jesus Christ that my Body after its Sleeping awhile in ]esus shall be committed unto my Soul that they may both be for ever with the Lord. Of what I shall leave behind me I make this following Disposall A11 my just debts being first paid (and by *y debts I mean whatever shall be provd to be soo after my decease or whatever my Executrix hereafter named can by diligent searching find out that I owe) I give to my Dear and adopted Child Mrs Isabella Edwards Widdow late of l)ean Street in Holbourn Parish three hundred pounds Sterlin [sic] (for the tender and matchless ffreindship she shewed both to rny Soul and body from our first Acquaintance in Ireland to the day of my death) to be paid to her by *y Executrix hereafter named as soon as she possibly can after my decease or in case the said Isabella Edwards sould dy" before me I give flfty pounds of the said three hundred pounds to Mr William Lutwich of London Goldsmith... I also give to my Adopted Child Mrs Isabella Edwards her own Picture in a Gilded fframe and also my Silver Spoon that Mr William Ashhurst sent to me that year I liv'd with him when he was Lord Mayor of the City of London - I also give to William Reading Nathaniel Reading and Thomas Reading my Cozens the Summ of thirty pounds Viz. -

Paying for Poetry at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century, with Particular Reference to Dryden, Pope, and Defoe

Paying for Poetry at the Turn of the Eighteenth Century, with Particular Reference to Dryden, Pope, and Defoe J. A. DOWNIE IT IS SOMETIMES insinuated that author-publisher relations changed once and for all as a consequence of Dryden’s contract with Jacob Tonson to publish a subscription edition of his translation of Virgil, and Pope’s subsequent agreement with Bernard Lintot to publish a translation of the Iliad. Both poets unquestionably made a lot of money out of these publications. Dryden should have received the proceeds of the 101 five-guinea subscriptions in their entirety, in accordance with his contract with Tonson, as well as an additional sum from the cheaper second subscription. In addition to agreeing to pay Dryden £200 in four instalments for the copyright of his translation of Virgil to encourage him to complete the project as speedily as possible, Tonson also paid the capital costs of the plates and alterations and the costs of the 101 copies for the first subscribers. He even made a contribution towards the costs of the copies of the second subscribers. John Barnard calculates that “in all Dryden received between £910 and £1,075 from Tonson and the subscribers, and probably £400 or £500 for his [three] dedications” (“Patrons” 177). Yet Dryden fell out with Tonson, and William Congreve and one Mr Aston were called in to mediate. “You always intended I shou[l]d get nothing by the Second Subscriptions,” Dryden complained to Tonson, “as I found from first to last” (Letters 77). After shopping around among other booksellers, however, Dryden came to think rather differently. -

Memoirs of the City of London and Its Celebrities (Volume 1)

Memoirs of the City of London and Its Celebrities (Volume 1) By John Heneage Jesse CHAPTER I TOWER HILL, ALLHALLOWS BARKING, CRUTCHED FRIARS, EAST SMITHFIELD, WAPPING. Illustrious Personages Executed on Tower Hill Melancholy Death of Otway Anecdote of Rochester Peter the Great Church of Allhallows Barking Seething Lane The Minories Miserable Death of Lord Cobham Goodman's Fields Theatre St. Katherine's Church Ratcliffe Highway Murders of the Marrs and Williamsons Execution Dock Judge Jeffreys Stepney. WHO is there whose heart is so dead to every generous impulse as to have stood without feelings of deep emotion upon that famous hill, where so many of the gallant and the powerful have perished by a bloody and untimely death ? Here fell the wise and witty Sir Thomas More ; the great Protector Duke of Somerset ; and the young and accomplished Earl of Surrey ! Here died the lofty Strafford and the venerable Laud ; the unbending patriot, Algernon Sidney, and the gay and graceful Duke of Monmouth ! Who is there who has not sought to fix in his mind's eye the identical spot where they fell, the exact site of the fatal stage and of its terrible paraphernalia ? Who is there who has not endeavoured to identify the old edifice ' from which the gallant Derwent water and the virtuous Kenmure were led through avenues (j.soldief$' fo-.ihfe.folock ? or who has not sought .forthe. -bouse '{adjeining the scaffold " where the gferitle 'Kilmameck'* breathed his last sigh, and where the intrepid Balmerino grasped affectionately, and for the last time, the -

Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment

Comp. by: pg2557 Stage : Revises1 ChapterID: 0001331932 Date:15/12/11 Time:04:58:00 Filepath:d:/womat-filecopy/0001331932.3D OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 15/12/2011, SPi Chapter 23 Historical Writing in Britain from the Late Middle Ages to the Eve of Enlightenment Daniel Woolf Historical writing in Britain underwent extraordinary changes between 1400 and 1700.1 Before 1500, history was a minor genre written principally by clergy and circulated principally in manuscript form, within a society still largely dependent on oral communication. By the end of the period, 250 years of print and steadily rising literacy, together with immense social and demographic change, had made history the most widely read of literary forms and the chosen subject of hundreds of writers. Taking a longer view of these changes highlights continuities and discontinuities that are obscured in shorter-term studies. Some of the continu- ities are obvious: throughout the period the past was seen predominantly as a source of examples, though how those examples were to be construed would vary; and the entire period is devoid, with a few notable exceptions, of historical works written by women, though female readership of history was relatively common- place among the nobility and gentry, and many women showed an interest in informal types of historical enquiry, often focusing on familial issues.2 Leaving for others the ‘Enlightened’ historiography of the mid- to late eighteenth century, the era of Hume, Robertson, and Gibbon, which both built on and departed from the historical writing of the previous generations, this chapter suggests three phases for the principal developments of the period from 1400 to 1 I am grateful to Juan Maiguashca, David Allan, and Stuart Macintyre for their comments on earlier drafts of this essay, which I dedicate to the memory of Joseph M.