The Lutes of the Santal | Bengt Fosshag

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Freebern, Charles L., 1934

THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Freebern, Charles L., 1934- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 06:04:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290233 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-6670 FREEBERN, Charles L., 1934- IHE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA/JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS. [Appendix "Pronounciation Tape Recording" available for consultation at University of Arizona Library]. University of Arizona, A. Mus.D., 1969 Music University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan CHARLES L. FREEBERN 1970 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED • a • 111 THE MUSIC OP INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS by Charles L. Freebern A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA. GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles L, Freebern entitled THE MUSIC OF INDIA, CHINA, JAPAN AND OCEANIA: A SOURCE BOOK FOR TEACHERS be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts &• 7?)• as. in? Dissertation Director fca^e After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Connnittee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" _ ^O^tLUA ^ AtrK. -

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta

Cultures of Instrument Making in Assam Upatyaka Dutta As Assam slowly recovers from the double whammy of COVID-19 pandemic and floods, I utilized every little opportunity to visit instrument makers living in the interior villages of Assam. My first visit was made to a Satra (Neo-vaishnavite monastery) by the name of Balipukhuri Satra on the outskirts of Tezpur (Sonitpur district), the cultural capital of Assam. There in the Satra, the family introduced me to three hundred years old folk instruments. A Sarinda, which is an archaic bowed string instrument, turns out to be one of their most prized possessions. Nobody in the family is an instrument maker, however, their ancestors had received the musical instruments from an Ahom king almost three hundred years back. The Sarinda remains in a dilapidated condition, with not much interest given to its restoration. Thus, the sole purpose that the instrument is serving is ornamentation. Fig 1: The remains of a Sarinda at Balipukhuri Satra The week after that was my visit to a village in Puranigudam, situated in Nagaon district of Assam. Two worshippers of Lord Shiva, Mr. Golap Bora and Mr. Prafulla Das, told tales of Assamese folk instruments they make and serenaded me with folk songs of Assam. Just before lunchtime, I visited Mr. Kaliram Bora and he helped me explore a range of Assamese instruments, the most interesting among which is the Kali. The Kali is a brass musical instrument. In addition to making instruments, Kaliram Bora is a well-known teacher of the Kali and has been working with the National Academy of Music, Dance and Drama’s Guru-shishya Parampara system of schools to imbibe education in Kali to select students of Assam. -

The Sarangi Family

THE SARANGI FAMILY 1. 1 Classification In the prestigious New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. the sarangi is described as follows : "A bowed chordophone occurring in a number of forms in the Indian subcontinent. It has a waisted body, a wide neck without frets and is usually carved from a single block of wood; in addition to its three or four strings it has one or two sets of sympathetic strings. The sarangi originated as a folk instrument but has been used increasingly in classical music." 1 Whereas this entry consists of only a few lines. the violin family extends to 72 pages. lea ding one to conclude that a comprehensive study of the sarangi has been sorely lacking for a long time. A cryptic description like the one above reveals next to nothing about this major Indian bowed instrument which probably originated at the same time as the violin. It also ignores the fact that the sarangi family comprises the largest number of Indian stringed instruments. What kind of sarangi did the authors visualize when they wrote these lines? Was it the large classical sarangi or one of the many folk types? In which musical context are these instruments used. and how important is the sarangi player? How does one play the sarangi? Who were the famous masters and what did they contribute? Many such questions arise when one talks about the sarangi. A person frnm Romhav-assuminq he is familiar with the sarangi-may have a different 2 picture in mind than someone from Jodhpur or Srinagar. -

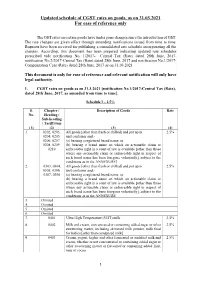

GST Notifications (Rate) / Compensation Cess, Updated As On

Updated schedule of CGST rates on goods, as on 31.03.2021 For ease of reference only The GST rates on certain goods have under gone changes since the introduction of GST. The rate changes are given effect through amending notifications issued from time to time. Requests have been received for publishing a consolidated rate schedule incorporating all the changes. According, this document has been prepared indicating updated rate schedules prescribed vide notification No. 1/2017- Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017, notification No.2/2017-Central Tax (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 and notification No.1/2017- Compensation Cess (Rate) dated 28th June, 2017 as on 31.03.2021 This document is only for ease of reference and relevant notification will only have legal authority. 1. CGST rates on goods as on 31.3.2021 [notification No.1/2017-Central Tax (Rate), dated 28th June, 2017, as amended from time to time]. Schedule I – 2.5% S. Chapter / Description of Goods Rate No. Heading / Sub-heading / Tariff item (1) (2) (3) (4) 1. 0202, 0203, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0204, 0205, unit container and,- 0206, 0207, (a) bearing a registered brand name; or 0208, 0209, (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or 0210 enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE] 2. 0303, 0304, All goods [other than fresh or chilled] and put up in 2.5% 0305, 0306, unit container and,- 0307, 0308 (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily], subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE 3. -

Other String Instruments Catalogue

. Product Catalogue for Other Strings Instruments Contents: 4 Strings Violin…………………………………………………………………………………...1 5 Strings Violin……………………...…………………………………………………………...2 Bulbul Tarang....…………………...…………………………………………………………...3 Classical Veena...…….………………………………………………………………………...4 Dilruba.…………………………………………………………………….…………………..5 Dotara……...……………………...…………………………………………………………..6 Egyptian Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………...7 Ektara..…………….………………………………………………………………………...8 Esraaj………………………………………………………………………………………10 Gents Tanpura..………………...…………………………………………………………11 Harp…………………...…………………………………………………………..............12 Kamanche……….……………………………………………………………………….13 Kamaicha……..…………………………………………………………………………14 Ladies Tanpura………………………………………………………………………...15 Lute……………………...……………………………………………………………..16 Mandolin…………………...…………………………………………………………17 Rabab……….………………………………………………………………………..18 Saarangi……………………………………………………………………………..22 Saraswati Veena………...………………………………………………………….23 Sarinda……………...………………………………………………………….......24 Sarod…….………………………………………………………………………...25 Santoor……………………………………………………………………………26 Soprano………………...………………………………………………………...27 Sor Duang……………………………………………………………………….28 Surbahar……………...…………………………………………………………29 Swarmandal……………….……………………………………………………30 Taus…………………………………………………………………………….31 Calcutta Musical Depot 28C, Shyama Prasad Mukherjee Road, Kolkata-700 025, West Bengal, India Ph:+91-33-2455-4184 (O) Mobile:+91-9830752310 (M) 24/7:+91-9830066661 (M) Email: [email protected] Web: www.calmusical.com /calmusical /calmusical 1 4 Strings Violin SKU: CMD/4SV/1600 -

South Asian Dance & Music Mapping Study

South Asian Dance & Music Mapping Study - APPENDICES Commissioned by: Arts Council England April 2020 December 2020 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendices to Report Contents Appendices Appendix 1 Consultation List 3 Appendix 2 Market Analysis 17 Appendix 3 Desk Research Literature Review 77 Appendix 4 Excel Mapping Docs with Macros (attached separately) Appendix 4a Excel Mapping Docs without Macros (attached separately) Appendix 5 Sector Survey Findings 121 December 2020 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendix 1: Consultation List Appendix 1 – Consultation List In total 103 South Asian musicians and/or dancers and stakeholders were consulted through one to one consultations and/or a series of round table sector discussions. South Asian Dance & Music: Consultation List – One to One Depth Interviews Name Organisation / Title 1. Seetal Kaur ACE Relationship Manager (Dance), Midlands & SA Dancer https://www.curveonline.co.uk/news/meet-the-artist-seetal-kaur/ 2. Mithila Sarma ACE Relationship Manager (Music) & SA Musician https://prsfoundation.com/grantees/women-make-music-mithila-sarma/ https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b061c3t4 3. Jan De Schynkel ACE Relationship Manager, Dance & Project Lead 4. Joe Shaw ACE Senior Officer, Policy & Research & Project Team 5. Victoria Merriman ACE Relationship Manager; Children Young People and Learning / Music Education 6. Laura Evans Relationship Manager, Dance 7. Raúl S-V Calderón Relationship Manager 8. Gabby Chelmicka ACE Relationship Manager, Music December 2020 3 Arts Council England South Asian Dance and Music Mapping Appendix 1: Consultation List Name Organisation / Title 9. Amelia Henderson ACE Relationship Manager, Combined Arts 10. Thomas Wildish ACE Relationship Manager, Theatre 11. -

T>HE JOURNAL MUSIC ACADEMY

T>HE JOURNAL OF Y < r f . MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY IrGHTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE ' AND ART OF MUSIC XXXVIII 1967 Part.' I-IV ir w > \ dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, ^n- the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there L ^ Narada ! ” ) EDITED BY v. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1967 PUBLISHED BY 1US1C ACADEMY, MADRAS a to to 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD, MADRAS-14 bscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. X \ \ !• ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES \ COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page i BaCk (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 99 20 .. 11. BaCk (Do.) 30 *# ” J6 INSIDE PAGES: i 1st page (after Cover) 99 18 io Other pages (eaCh) 99 15 .. 9 PreferenCe will be given (o advertisers of musiCal ® instruments and books and other artistic wares. V Special positions and speCial rates on appliCation. t NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Ragb Editor, Journal of the MusiC ACademy, Madras-14. Articles on subjects of musiC and dance are accepte publication on the understanding that they are Contributed to the Journal of the MusiC ACademy. f. AIT manuscripts should be legibly written or preferabl; written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and be sigoed by the writer (giving his address in full). I The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for tb expressed by individual contributors. AH books, advertisement moneys and cheques du> intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V, B Editor. CONTENTS Page T XLth Madras MusiC Conference, 1966 OffiCial Report .. -

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments with the General

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments With the general background and perspective of the entire field of Indian Instrumental Music as explained in previous chapters, this study will now proceed towards a brief description of Indian Musical Instruments. Musical Instruments of all kinds and categories were invented by the exponents of the different times and places, but for the technical purposes a systematic-classification of these instruments was deemed necessary from the ancient time. The classification prevalent those days was formulated in India at least two thousands years ago. The first reference is in the Natyashastra of Bharata. He classified them as ‘Ghana Vadya’, ‘Avanaddha Vadya’, ‘Sushira Vadya’ and ‘Tata Vadya’.1 Bharata used word ‘Atodhya Vadya’ for musical instruments. The term Atodhya is explained earlier than in Amarkosa and Bharata might have adopted it. References: Some references with respect to classification of Indian Musical Instruments are listed below: 1. Bharata refers Musical Instrument as ‘Atodhya Vadya’. Vishnudharmotta Purana describes Atodhya (Ch. XIX) of four types – Tata, Avnaddha, Ghana and Sushira. Later, the term ‘Vitata’ began to be used by some writers in place of Avnaddha. 2. According to Sangita Damodara, Tata Vadyas are favorite of the God, Sushira Vadyas favourite of the Gandharvas, whereas Avnaddha Vadyas of the Rakshasas, while Ghana Vadyas are played by Kinnars. 3. Bharata, Sarangdeva (Ch. VI) and others have classified the musical instruments under four heads: 1 Fundamentals of Indian Music, Dr. Swatantra Sharma , p-86 53 i. Tata (String Instruments) ii. Avanaddha (Instruments covered with membrane) iii. Sushira (Wind Instruments) iv. Ghana (Solid, or the Musical Instruments which are stuck against one another, such as Cymbals). -

Background Material on Exempted Services Under GST

Background Material on Exempted Services under GST The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (Set up by an Act of Parliament) New Delhi © The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission, in writing, from the publisher. DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this book are of the author(s). The Institute of Chartered Accountants of India may not necessarily subscribe to the views expressed by the author(s). The information cited in this book has been drawn from various sources. While every effort has been made to keep the information cited in this book error free, the Institute or any officer of the same does not take the responsibility for any typographical or clerical error which may have crept in while compiling the information provided in this book. First Edition : January, 2018 Committee/Department : Indirect Taxes Committee E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.idtc.icai.org / www.icai.org Published by : The Publication Department on behalf of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, ICAI Bhawan, Post Box No. 7100, Indraprastha Marg, New Delhi - 110 002. Foreword In the GST regime, when a supply of goods and/or services falls within the purview of charging Section, such supply is chargeable to GST. However, for determining the liability to pay the tax, one needs to further check whether such supply of goods and/or services are exempt from tax or not. -

The Arunachal Pradesh Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED by AUTHORITY

The Arunachal Pradesh Gazette EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 411, Vol. XXIV, Naharlagun, Wednesday, October 4, 2017 Asvina 12, 1939 (Saka) GOVERNMENT OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH DEPARTMENT OF TAX & EXCISE ITANAGAR ————— Notification No. 28/2017-State Tax (Rate) The 26th September, 2017 No. GST/24/2017.— In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of Section 11 of the Arunachal Pradesh Goods and Services Tax Act, 2017 (7 of 2017), the State Government, on the recommendations of the Council, hereby makes the following amendments in the notification of the Government of Arunachal Pradesh, Department of Tax & Excise, No.2/2017-State Tax (Rate), dated the 28th June, 2017, published in the Extra ordinary Gazette of Arunachal Pradesh, vide number 192, Vol XXIV, dated the 30th June, 2017, namely:- In the said notification,- (B) in the Schedule,- (i) against serial number 27, in column (3), for the words “other than put up in unit containers and bearing a registered brand name”, the words, brackets and letters “other than those put up in unit container and,- (a) bearing a registered brand name; or (b) bearing a brand name on which an actionable claim or enforceable right in a court of law is available [other than those where any actionable claim or enforceable right in respect of such brand name has been foregone voluntarily, subject to the conditions as in the ANNEXURE I]”, shall be substituted ; (jj) against serial numbers 29 and 45, in column (3), for the words “other than put up in unit container and bearing a registered brand -

Anthropological Account of Traditional Musical Instruments Abstract

Vol. II, No. I (2017) p- ISSN: 2708-2091 e- ISSN: 2708-3586 L- ISSN: 2708-2091 Pages: 1 – 9 Anthropological Account of Traditional Musical Instruments URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gsr.2017(II-I).01 | DOI: 10.31703/gsr.2017(II-I).01 Nida Rehman* Abid Ghafoor Chaudhry† Abstract The art of making a musical instrument, playing it and to move or dance to that instrument is duly considered to be an abhorrent act in Pakistan. The use of musical instruments in Pakistan is going to be extinct over time. Research in Pakistan has yet to be done in this area. The musical instruments are source of bread and butter for artists and performers as their lives are connected with these instruments. Both instrument performers and the artists were selected as respondents. The data was collected from 25 artists and performers through cluster samplings. Based on the interviews, the importance of instruments, their values and methods on the rhythms were collected from the performers (participants). The government and art Institutions in the country can play a pivotal role in saving and preserving the instruments and the artists classical culture. Key Words: Instrument, Artist, Culture, Professional Dancer Introduction Human being has always been interested in echo or sound. The person who plays the instruments is often the performer and maker. Instrument are made and used in naturally form. The materials consist of wood, gourds, turtle shells, animal horns or skin. They decorate their instruments. They are considered works of art. Music understands and builds the relationship of different instruments.