UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’S Back to the Islands Special Liturgy to Mark Priests Navigate Why Didn’T for Incoming Head of 75Th Anniversary of the U.S

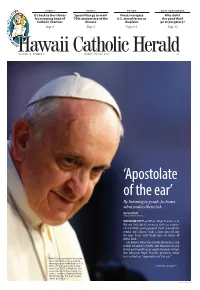

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’s back to the Islands Special liturgy to mark Priests navigate Why didn’t for incoming head of 75th anniversary of the U.S. armed forces as the good thief Catholic Charities diocese chaplains go to purgatory? Page 3 Page 5 Page 8-9 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 14 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 29, 2016 Herald$1 ‘Apostolate of the ear’ By listening to youth, he hears what makes them tick By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY — When Pope Francis is in Poland July 26-31 to meet with an expect- ed 2 million young people from around the world, he’s there with a firm idea of the dreams, fears and challenges so many of them face. He knows what lies inside the hearts and minds of today’s youth, not because of any third-party polling or sophisticated survey, but because Pope Francis practices what he’s called an “apostolate of the ear.” Pope Francis is pictured leaving an encounter with young people in the piazza outside the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi, Italy, Continued on page 10 in this Oct. 4, 2013, file photo. The pope plans to visit Assisi Aug. 4 to make a “simple and private” visit to the Portiuncola, the stone chapel rebuilt by St. Francis. CNS photo/Paul Haring 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 29, 2016 Official notices Hawaii Bishop’s calendar Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be attended by Bishop’s Catholic delegate] Herald July 25-31, World Youth Day, Kraków, Poland. -

Anatomy of Melancholy by Democritus Junior

THE ANATOMY OF MELANCHOLY WHAT IT IS WITH ALL THE KINDS, CAUSES, SYMPTOMS, PROGNOSTICS, AND SEVERAL CURES OF IT IN THREE PARTITIONS; WITH THEIR SEVERAL SECTIONS, MEMBERS, AND SUBSECTIONS, PHILOSOPHICALLY, MEDICINALLY, HISTORICALLY OPENED AND CUT UP BY DEMOCRITUS JUNIOR [ROBERT BURTON] WITH A SATIRICAL PREFACE, CONDUCING TO THE FOLLOWING DISCOURSE PART 2 – The Cure of Melancholy Published by the Ex-classics Project, 2009 http://www.exclassics.com Public Domain CONTENTS THE SYNOPSIS OF THE SECOND PARTITION............................................................... 4 THE SECOND PARTITION. THE CURE OF MELANCHOLY. .............................................. 13 THE FIRST SECTION, MEMBER, SUBSECTION. Unlawful Cures rejected.......................... 13 MEMB. II. Lawful Cures, first from God. .................................................................................... 16 MEMB. III. Whether it be lawful to seek to Saints for Aid in this Disease. ................................ 18 MEMB. IV. SUBSECT. I.--Physician, Patient, Physic. ............................................................... 21 SUBSECT. II.--Concerning the Patient........................................................................................ 23 SUBSECT. III.--Concerning Physic............................................................................................. 26 SECT. II. MEMB. I....................................................................................................................... 27 SUBSECT. I.--Diet rectified in substance................................................................................... -

22, 2017 Hawai'i Convention Center

2017 DAMIEN AND MARIANNE CATHOLIC CONFERENCE October 20 – 22, 2017 Hawai’i Convention Center CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 20 Saturday, October 21 Sunday, October 22 Exhibit Hall Open Registration Check-in Registration Check-In 8:00am 7:00am 7:30am Registration Check-In Exhibit Hall Open Exhibit Hall Open Opening Ceremony 10:00am 8:30am Tongan Mass 8:30am Rosary Keynote Speaker 10:30am 10:00am Keynote Speaker 9:00am Keynote Speaker Lunch Break 12:15pm 11:15am Breakout Sessions 10:30am Performing Arts Play Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 12:30pm 12:15pm Lunch Break 12:15pm Lunch Break Reconciliation Prayer Service – Divine Mercy Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 3:00pm 12:30pm 1:00pm Closing Mass Chaplet Reconciliation Welcome from Bishop Larry Silva 1:45pm & 3:45pm Breakout Sessions Hawaiian Mass 3:00pm Dinner Break 5:00pm 4:00pm Dinner Break Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 5:00pm 4:00pm Reconciliation Reconciliation Keynote Speaker 7:00pm 7:15pm Breakout Sessions Youth Activities 8:00pm 8:30pm Concert Conference Sessions and Prayer Service Friday, October 20 10:00am 3:00pm – 5:00pm OPENING CEREMONY & SAINTS AWARD DIVINE MERCY CHAPLET Oli Prayer acknowledging Ke Akua, those who are present, and the In 1935, St. Faustina received a vision of an angel sent by God to reason for the gathering. chastise a certain city. She began to pray for mercy, but her prayers were powerless. Suddenly she saw the Holy Trinity and felt the 10:30am – 11:30am power of Jesus’ grace within her. At the same time she found P101 EXTRAORDINARY VISIONS! herself pleading with God for mercy with words she heard interiorly. -

The Lives of the Saints

'"Ill lljl ill! i j IIKI'IIIII '".'\;\\\ ','".. I i! li! millis i '"'''lllllllllllll II Hill P II j ill liiilH. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library BR 1710.B25 1898 v.7 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 598 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082598 *— * THE 3Utoe* of tt)e Saints; REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SEVENTH *- -* . l£ . : |£ THE Itoes of tfje faints BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in 16 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SEVENTH KttljJ— PARTI LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &° ' 1 NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII *• — ;— * Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co. At the Eallantyne Press *- -* CONTENTS' PAGE S. Athanasius, Deac. 127 SS. Aaron and Julius . I SS. AudaxandAnatholia 203 S. Adeodatus . .357 „ Agilulf . 211 SS. Alexanderandcomp. 207 S. Amalberga . , . 262 S. Bertha . 107 SS. AnatholiaandAudax 203 ,, Bonaventura 327 S. Anatolius,B. of Con- stantinople . 95 „ Anatolius, B.ofLao- dicea . 92 „ Andrew of Crete 106 S. Canute 264 Carileff. 12 „ Andrew of Rinn . 302 „ ... SS. Antiochus and SS. Castus and Secun- dinus Cyriac . 351 .... 3 Nicostra- S. Apollonius . 165 „ Claudius, SS. Apostles, The Sepa- tus, and others . 167 comp. ration of the . 347 „ Copres and 207 S. Cyndeus . 277 S. Apronia . .357 SS. Aquila and Pris- „ Cyril 205 Cyrus of Carthage . -

Select Bibliography

select bibliography primary sources archives Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archive of the Archbishop of Mechelen), Brussels, Belgium. Archive at St. Anthony Convent and Motherhouse, Sisters of St. Francis, Syracuse, NY. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Honolulu. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Leuven, Belgium. Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. kalaupapa manuscripts and collections Bigler, Henry W. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cannon, George Q. Journals. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cluff, Harvey Harris. Autobiography. Handwritten copy. Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Decker, Daniel H. Mission Journal, 1949–1951. Courtesy of Daniel H. Decker. Farrer, William. Biographical Sketch, Hawaiian Mission Report, and Diary of William Farrer, 1946. Copied from the original and housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Gibson, Walter Murray. Diary. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Green, Ephraim. Diary. Microfilm copy, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Halvorsen, Jack L. Journal and correspondence. Copies in possession of the author. Hammond, Francis A. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hawaii Mission President’s Records, 1936–1964. LR 3695 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haycock, D. Arthur. Correspondence, 1954–1961. Courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle. “Incoming Letters of the Board of Health.” Hansen’s Disease. -

Download PDF Datastream

DOORWAYS TO THE DEMONIC AND DIVINE: VISIONS OF SANTA FRANCESCA ROMANA AND THE FRESCOES OF TOR DE’SPECCHI BY SUZANNE M. SCANLAN B.A., STONEHILL COLLEGE, 2002 M.A., BROWN UNIVERSITY, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART AND ARCHITECTURE AT BROWN UNIVERSITY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY, 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Suzanne M. Scanlan ii This dissertation by Suzanne M. Scanlan is accepted in its present form by the Department of History of Art and Architecture as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date_____________ ______________________________________ Evelyn Lincoln, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date______________ ______________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Reader Date______________ ______________________________________ Caroline Castiglione, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ _____________________________________ Sheila Bonde, Dean of the Graduate School iii VITA Suzanne Scanlan was born in 1961 in Boston, Massachusetts and moved to North Kingstown, Rhode Island in 1999. She attended Stonehill College, in North Easton, Massachusetts, where she received her B.A. in humanities, magna cum laude, in 2002. Suzanne entered the graduate program in the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Brown University in 2004, studying under Professor Evelyn Lincoln. She received her M.A. in art history in 2006. The title of her masters’ thesis was Images of Salvation and Reform in Poccetti’s Innocenti Fresco. In the spring of 2006, Suzanne received the Kermit Champa Memorial Fund pre- dissertation research grant in art history at Brown. This grant, along with a research assistantship in Italian studies with Professor Caroline Castiglione, enabled Suzanne to travel to Italy to begin work on her thesis. -

Musica Sanat Corpus Per Animam': Towar Tu Erstanding of the Use of Music

`Musica sanat corpus per animam': Towar tU erstanding of the Use of Music in Responseto Plague, 1350-1600 Christopher Brian Macklin Doctor of Philosophy University of York Department of Music Submitted March 2008 BEST COPY AVAILABLE Variable print quality 2 Abstract In recent decadesthe study of the relationship between the human species and other forms of life has ceased to be an exclusive concern of biologists and doctors and, as a result, has provided an increasingly valuable perspective on many aspectsof cultural and social history. Until now, however, these efforts have not extended to the field of music, and so the present study representsan initial attempt to understand the use of music in Werrn Europe's responseto epidemic plague from the beginning of the Black Death to the end of the sixteenth century. This involved an initial investigation of the description of sound in the earliest plague chronicles, and an identification of features of plague epidemics which had the potential to affect music-making (such as its geographical scope, recurrence of epidemics, and physical symptoms). The musical record from 1350-1600 was then examined for pieces which were conceivably written or performed during plague epidemics. While over sixty such pieces were found, only a small minority bore indications of specific liturgical use in time of plague. Rather, the majority of pieces (largely settings of the hymn Stella coeli extirpavit and of Italian laude whose diffusion was facilitated by the Franciscan order) hinted at a use of music in the everyday life of the laity which only occasionally resulted in the production of notated musical scores. -

Linda Lehman Receives the Damien-Dutton Award for 2014

LINDA LEHMAN RECEIVES THE DAMIEN-DUTTON AWARD FOR 2014 The International Leprosy Association is proud to announce that Linda Lehman OTR/L, MPH, C.Ped has been selected to receive the prestigious Damien-Dutton Award for 2014. Lehman has been selected for making a significant and lasting contribution to the global fight against leprosy. For more than three decades, she has travelled the world providing technical expertise and training on prevention of disability to everyone from ministries of health to community health workers. The award was created by the Damien-Dutton Society for Leprosy Aid, Inc., a non- profit organization dedicated to ridding the world of leprosy. It is named after both Father Damien, a Belgian priest, canonized in 2009 for the care he gave to people affected by leprosy on the island of Molokai, Hawaii, and after Joseph Dutton, a U.S. civilian war veteran, who helped Father Damien. Every year since 1953, the Damien-Dutton Society has presented an award to a notable person who has made a significant contribution towards the conquest of leprosy. Past award recipients include John F. Kennedy (posthumously), Dr Paul and Dr Margaret Brand and Mother Teresa. American Leprosy Missions received the award in 1981. An American Leprosy Missions’ Senior Advisor for Morbidity Management & Disability Prevention, Ms. Lehman is trained as an occupational therapist, has a Master of Public Health degree from Emory University and a certification in pedorthics. She has developed training materials endorsed by the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). Linda Lehman has strong links with Brazil and its National Leprosy Control Program where she served as advisor in her field of expertise for several years. -

Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time

!%JR:75()H QGV`(5( ( ! TwentyTwenty----NinthNinth Sunday in Ordinary Time Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 21, 2018 Saint Andrew the Apostle Parish Page 2 Stewardship is a way of life. Today, October 21, 2018 Tithing is God’s Plan for Giving : World Mission Sunday October 7, 2018 CCD Classes Tithing Income $8,108.10 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School Tithe $ 810.81 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool $7,297.29 Online $ 752.00 R.C.I.A —Monday, October 22, 7:00—8:30pm, School Multipurpose Room Actual Income $8,049.29 Weekly Budget $7,500.00 Bible Study —Tuesday, October 23, 9:00—11:00 am and 6:30—8:30 pm both in the Parish Meeting Room. Poor Box $ 42.50 Next Weekend, October 27/28, 2018 Children’s Offerings $ 2.00 CCD Classes—Sunday 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School This week: 10/21: For the Family 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool of Garrett Seech, Christina Youth Group Soup Sales – after Masses in School hall Sentelle, Anna Marie Pickert; Kathaleen Bryan, Keith Wolfrey, Aliene Minister Schedule Misitis, Kellie Reiber, Philip Baker, Fred Eisenhart , Tom Lopresti, Frank Lago, If you are unable to serve, please find a substitute. Thank you. Adele Hanson, Gretchen Bertuccini , Chauney McGarney, Zoey Walker , Perry Saturday, October 27, 5pm: Fath, Lisa White, James J. Thomas, Cathy Kinman, Ed EMHC —Mike Geoffroy, Carmen Krawczak, Janet Bryner, Earl Bennett, Ty Long, Robin L. Fraley , Robin Stockton, 1 Needed ; Altar Servers —Ben Holderness, Gordon Fath, Jr., A Special Intention for Williams, Caiden -

Tanulmányt Alap

'W,- Ö -χ "V& > f\ • % :\i.\<; YA iíoiísza(ÍI Κ I I; Л Ь A I TANULMÁNYT ALAP \ í \i 1 í ^M'íi^i íí'k'Vi ^rjl'x" • ч r • M /w i i ι ΛΙ Γ,ΓνΜ χ, i l i, Λ EIN r \ Ι UN : \'I '/ Jο^ ιv i' ,·л \ τi JA w. »g ? .· νν тi м\ Ул V wO/jу Vί 71\ ϊ ilί i \ i Τ ? VEZÉ KORMÁNYOK. \ r~ \ ι X / \ / \ Λ VALLAS KS ΚΟΖΟΚΤΛΤΑΚΠίΥΙ Μ. Κ11. MIXI ST КI ί MK< Míi/ASÁI'.OL. Ρ UDAPESTEN. NYOMATOTT Λ ΜΛΟΥΛΙί ΚίΙί. J.OYΈΤΚΜΙ KÖN ΥΥΝ ΥΟ.ΜΟΛΒΛΧ. № η V' Y. 1 S A f) ' V Ov ' 4 9 / ; 4: с f А ζ' г χ' {1 ί f ί A MAGYARORSZÁGI KIR TANULMÁNYI ALAP JOGI r _ r r, TERMESZETENEK MEGVIZSGÁL AS ARA SZOLGÁLÓ YE ZÉRÓK MÁN Y OK. A VALLÁS ÉS KÖZOKTATÁSÜGYI M. KIR. MINISTER MEGBÍZÁSÁBÓL. ÁLL. POLGÁRI I3K. TANI10KÉPZÖ INT. KÖNYVTÁRA jf Érteett: 19 dÂÂ^s1 Leltári szÁm Csoportszám·^ | BUDAPESTEN. NYOMATOTT A MAGYAR KIR. EGYETEMI KÖNYVNYOMDÁBAN. A magyarországi kir. tanulmányi alapjogi természetének megvizsgálására szolgáló vezérokmányok jegyzéke. Lap. Lap. I. XIV. Kelemen pápának a jezsuita-rend meg- IX. D. e. Mária Terézia római császárné és ma- szüntetése iránt 1773.* évi julius 21-én kiadott gyar királynő alapitó-levele 1780. évi marczius brevéje 1 25-éről a jezsuita-rend vagyonából a magyar és horvát tanulmányi alap alakítása, és a magyar II. D. e. Mária Terézia római császárné és magyar tanulmányi és az egyetemi alap némely javainak királynőnek a m. k. helytartótanácshoz 1773. kicserélése iránt 35 évi september 20-án intézett leirata, melylyel a megszüntetett jezsuita-rend vagyonának a X. -

Abstract the Catholic Witness During Memphis

ABSTRACT THE CATHOLIC WITNESS DURING MEMPHIS YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMICS OF THE 1870s: A DESCRIPTION AND VINDICATION Elisabeth C. Sims Director: Dr. Micheal Foley, Ph.D. In the 1870s, several yellow fever epidemics struck Memphis causing a calamity that shook the entire United States. The yellow fever epidemics in Memphis were some of the deadliest and most terrifying events of American urban history, killing more people than the Chicago Fire, San Francisco earthquake, and the Johnstown flood combined. A disaster for both the city and the region with implications for medical history, social history, and economic history, the yellow fever epidemics are of interest from a variety of historical perspectives and serve as a locus of research for a variety of disciplines. This project will examine historical narratives that describe the ways in which Catholic religious groups in Memphis responded to this crisis, and it will seek to discern how the underreported Catholic narrative of epidemics contributes something distinctive to Memphis history. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: __________________________________________ Dr. Micheal Foley, Great Texts APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: __________________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Corey, Director DATE:________________________ THE CATHOLIC WITNESS DURING MEMPHIS YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMICS OF THE 1870s: A DESCRIPTION AND VINDICATION A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Elisabeth C. Sims Waco, Texas May 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments iii. Dedication iv. Epigraph v. Introduction 1 Chapter One: Historic Narratives and the Priesthood 10 Chapter Two: The Sisters 34 Chapter Three: Public Memory 40 Appendix 46 Bibliography 59 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I am indebted my wonderful professors. -

Corsican Root and Branch

A JOURNAL OF ORTHODOX FAITH AND CULTURE ROAD TO EMMAUS Help support Road to Emmaus Journal. The Road to Emmaus staff hopes that you find our journal inspiring and useful. While we offer our past articles on-line free of charge, we would warmly appreciate your help in covering the costs of producing this non-profit journal, so that we may continue to bring you quality articles on Orthodox Christianity, past and present, around the world. Thank you for your support. Please consider a donation to Road to Emmaus by visiting the Donate page on our website. CORSICAN ROOT AND BRANCH An Interview with Josephine Antherieu RTE: Josephine, you are from the island of Corsica and you had a rather clas- sical education. Was that what led you to Orthodoxy? JOSEPHINE: Yes. I was formerly a high-school teacher of philosophy and classical languages – Greek, Latin, and Old French. Later, I changed my pro- fession and am now a city planner for Aix-en-Provence. I no longer deal with abstract ideas, but with buildings and streets, things physical and concrete. My father died about about twenty years ago and now I have my mother, Silouani, my sister, Annie, and her son, Christophe. My grandmother lived until just recently. Our family is from the island of Corsica, and we are the first Orthodox Christians on Corsica since the schism. The way I came to Orthodoxy was like a fairy tale. One day I heard of a man who was said to be “spiritual,” and although I had never done anything like this before, I went to see him.