Abstract the Catholic Witness During Memphis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’S Back to the Islands Special Liturgy to Mark Priests Navigate Why Didn’T for Incoming Head of 75Th Anniversary of the U.S

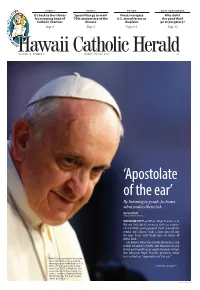

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’s back to the Islands Special liturgy to mark Priests navigate Why didn’t for incoming head of 75th anniversary of the U.S. armed forces as the good thief Catholic Charities diocese chaplains go to purgatory? Page 3 Page 5 Page 8-9 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 14 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 29, 2016 Herald$1 ‘Apostolate of the ear’ By listening to youth, he hears what makes them tick By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY — When Pope Francis is in Poland July 26-31 to meet with an expect- ed 2 million young people from around the world, he’s there with a firm idea of the dreams, fears and challenges so many of them face. He knows what lies inside the hearts and minds of today’s youth, not because of any third-party polling or sophisticated survey, but because Pope Francis practices what he’s called an “apostolate of the ear.” Pope Francis is pictured leaving an encounter with young people in the piazza outside the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi, Italy, Continued on page 10 in this Oct. 4, 2013, file photo. The pope plans to visit Assisi Aug. 4 to make a “simple and private” visit to the Portiuncola, the stone chapel rebuilt by St. Francis. CNS photo/Paul Haring 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 29, 2016 Official notices Hawaii Bishop’s calendar Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be attended by Bishop’s Catholic delegate] Herald July 25-31, World Youth Day, Kraków, Poland. -

22, 2017 Hawai'i Convention Center

2017 DAMIEN AND MARIANNE CATHOLIC CONFERENCE October 20 – 22, 2017 Hawai’i Convention Center CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 20 Saturday, October 21 Sunday, October 22 Exhibit Hall Open Registration Check-in Registration Check-In 8:00am 7:00am 7:30am Registration Check-In Exhibit Hall Open Exhibit Hall Open Opening Ceremony 10:00am 8:30am Tongan Mass 8:30am Rosary Keynote Speaker 10:30am 10:00am Keynote Speaker 9:00am Keynote Speaker Lunch Break 12:15pm 11:15am Breakout Sessions 10:30am Performing Arts Play Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 12:30pm 12:15pm Lunch Break 12:15pm Lunch Break Reconciliation Prayer Service – Divine Mercy Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 3:00pm 12:30pm 1:00pm Closing Mass Chaplet Reconciliation Welcome from Bishop Larry Silva 1:45pm & 3:45pm Breakout Sessions Hawaiian Mass 3:00pm Dinner Break 5:00pm 4:00pm Dinner Break Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 5:00pm 4:00pm Reconciliation Reconciliation Keynote Speaker 7:00pm 7:15pm Breakout Sessions Youth Activities 8:00pm 8:30pm Concert Conference Sessions and Prayer Service Friday, October 20 10:00am 3:00pm – 5:00pm OPENING CEREMONY & SAINTS AWARD DIVINE MERCY CHAPLET Oli Prayer acknowledging Ke Akua, those who are present, and the In 1935, St. Faustina received a vision of an angel sent by God to reason for the gathering. chastise a certain city. She began to pray for mercy, but her prayers were powerless. Suddenly she saw the Holy Trinity and felt the 10:30am – 11:30am power of Jesus’ grace within her. At the same time she found P101 EXTRAORDINARY VISIONS! herself pleading with God for mercy with words she heard interiorly. -

Catholic Deacons and the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick

St. Norbert College Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College Master of Theological Studies Honors Theses Master of Theological Studies Program Spring 2020 Catholic Deacons and the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick Michael J. Eash Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/mtshonors Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, New Religious Movements Commons, and the Religious Education Commons Recommended Citation Eash, Michael J., "Catholic Deacons and the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick" (2020). Master of Theological Studies Honors Theses. 2. https://digitalcommons.snc.edu/mtshonors/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master of Theological Studies Program at Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theological Studies Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ St. Norbert College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Catholic Deacons and the Sacrament of the Anointing of the Sick Michael J. Eash Abstract An examination to discern if Roman Catholic deacons should be allowed to sacramentally anoint the sick. This includes a review of the current rite of Anointing of the Sick through is development. The Catholic diaconate is examined in historical context with a special focus on the revised diaconate after 1967. Through these investigations it is apparent that there is cause for dialog within the Church considering current pastoral realities in the United States. The paper concludes that deacons should have the faculty to anoint the sick as ordinary ministers when it is celebrated as a separate liturgical rite. -

Select Bibliography

select bibliography primary sources archives Aartsbisschoppelijk Archief te Mechelen (Archive of the Archbishop of Mechelen), Brussels, Belgium. Archive at St. Anthony Convent and Motherhouse, Sisters of St. Francis, Syracuse, NY. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Honolulu. Archives of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts, Leuven, Belgium. Bishop Museum Archives, Honolulu. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. kalaupapa manuscripts and collections Bigler, Henry W. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cannon, George Q. Journals. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Cluff, Harvey Harris. Autobiography. Handwritten copy. Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Decker, Daniel H. Mission Journal, 1949–1951. Courtesy of Daniel H. Decker. Farrer, William. Biographical Sketch, Hawaiian Mission Report, and Diary of William Farrer, 1946. Copied from the original and housed in the L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. Gibson, Walter Murray. Diary. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Green, Ephraim. Diary. Microfilm copy, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lā‘ie, HI. Halvorsen, Jack L. Journal and correspondence. Copies in possession of the author. Hammond, Francis A. Journal. Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Hawaii Mission President’s Records, 1936–1964. LR 3695 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City. Haycock, D. Arthur. Correspondence, 1954–1961. Courtesy of Lynette Haycock Dowdle and Brett D. Dowdle. “Incoming Letters of the Board of Health.” Hansen’s Disease. -

Catholics: a Sacramental People the Church in the 21St Century Center Serves As a Catalyst and a Resource for the Renewal of the Catholic Church in the United States

spring 2012 a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the catholic church catholics: a sacramental people The Church in the 21st Century Center serves as a catalyst and a resource for the renewal of the Catholic Church in the United States. about the editor from the c21 center director john f. baldovin, s.j., professor of historical and liturgical theology at the aboutBoston theCollege editor School of Theology and Dear Friends: richardMinistry, lennanreceived, ahis priest Ph.D. of in the religious The 2011–12 academic year marks the ninth year since the Church in the 21st Century Diocesestudies from of Maitland-Newcastle Yale University in 1982. in Fr. initiative was established by Fr. William P. Leahy, S.J., president of Boston College. And the Australia,Baldovin is is a professor member of thesystematic New York theologyProvince inof the SchoolSociety ofof TheologyJesus. He current issue of C21 Resources on Catholics: A Sacramental People is the 18th in the series of andhas servedMinistry as at advisor Boston to College, the National where Resources that spans this period. heConference also chairs of theCatholic Weston Bishops’ Jesuit The center was founded in the midst of the clerical sexual abuse crisis that was revealed in Department.Committee on He the studied Liturgy theology and was a atmember the Catholic of the InstituteAdvisory ofCommittee Sydney, Boston and the nation in 2002. C21 was intended to be the University’s response to this crisis theof the University International of Oxford, Commission and the on and set as its mission the goals of becoming a catalyst and resource for the renewal of the UniversityEnglish in theof Innsbruck, Liturgy. -

Prayers for the Sick and Dying

Preparing for Heaven Series Fr. Martin Pitstick, Updated 7/31/2015. PRAYERS FOR THE SICK AND DYING Recommended Prayers and Scriptures May be used over a period of hours or days as you keep vigil at the bedside of a loved one who is preparing to go home to the Lord. These prayers will console the dying and give comfort to those who attend them. “The Lord Jesus says, I go to prepare a place for you, and I will come again to take you to myself.” John 14:2-3 CATHOLIC GUIDELINES FOR THE DYING When someone faces a life-threatening condition, a priest should be called. If they are unbaptized, a priest may baptism them. If a priest is not available, anyone can baptize in danger of death by pouring clean water over the head and saying “I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.” This should only be done if it is in accord with the desire of the sick person. If they are a baptized, non-Catholic, who wishes to become Catholic, and are in danger of death, a priest can receive them into the Catholic Church, confirm them and give them Holy Communion and the Anointing of the Sick. For Catholics, a priest can hear their Confession, giving them Absolution, the Anointing of the Sick, and Holy Communion (if they are able to receive). These three sacraments are the “Last Sacraments,” or the “Last Rites.” For those in immediate danger of death, an Apostolic Pardon may also be given by the priest, which grants a Plenary Indulgence. -

Memorial Services in the Byzantine Churches ~ Giving a Supper to Those Setting out on a Journey

ADDENDUM ~ VIATICUM: Among the ancient Greeks the custom prevailed of ~ Memorial Services in the Byzantine Churches ~ giving a supper to those setting out on a journey. This was called Ὁδοιπόριον hodoiporion". The provision of all things necessary for such a journey, viz. food, Traditionally, in addition to the service on the day of death, the «Panachida» money, clothes, utensils and expense, was called ἐφόδιον / ephódion. The or «Memorial Service for the Faithful Departed» is served at the request of adjectival equivalent in Latin of both these words is viaticus, i.e. "of or pertaining the relatives of an individual departed person on the following occasions: to a road or journey [“via” in Latin]". Subsequently the noun "viaticum" Third day after death (many times this is also the day of burial) figuratively meant the provision for the journey of life and finally by metaphor the Ninth day provision for the passage out of this world into the next. It is in this last meaning Fortieth day that the word is used in sacred liturgy. First anniversary of death Formerly VIATICUM meant anything that gave spiritual strength and comfort to After the first year, the departed is then remember at the dying and enabled them to make the journey into eternity with greater the five «All Souls Saturdays», but may be remembered confidence and security. For this reason anciently not only any sacrament at any time throughout the year if the family so administered to persons at the point of death, baptism, confirmation, penance, chooses. The above is the general pattern followed although there can be holy unction, Eucharist, but even prayers offered up or good works performed by much variation among the Churches of the Greeks and Slavs. -

Linda Lehman Receives the Damien-Dutton Award for 2014

LINDA LEHMAN RECEIVES THE DAMIEN-DUTTON AWARD FOR 2014 The International Leprosy Association is proud to announce that Linda Lehman OTR/L, MPH, C.Ped has been selected to receive the prestigious Damien-Dutton Award for 2014. Lehman has been selected for making a significant and lasting contribution to the global fight against leprosy. For more than three decades, she has travelled the world providing technical expertise and training on prevention of disability to everyone from ministries of health to community health workers. The award was created by the Damien-Dutton Society for Leprosy Aid, Inc., a non- profit organization dedicated to ridding the world of leprosy. It is named after both Father Damien, a Belgian priest, canonized in 2009 for the care he gave to people affected by leprosy on the island of Molokai, Hawaii, and after Joseph Dutton, a U.S. civilian war veteran, who helped Father Damien. Every year since 1953, the Damien-Dutton Society has presented an award to a notable person who has made a significant contribution towards the conquest of leprosy. Past award recipients include John F. Kennedy (posthumously), Dr Paul and Dr Margaret Brand and Mother Teresa. American Leprosy Missions received the award in 1981. An American Leprosy Missions’ Senior Advisor for Morbidity Management & Disability Prevention, Ms. Lehman is trained as an occupational therapist, has a Master of Public Health degree from Emory University and a certification in pedorthics. She has developed training materials endorsed by the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP). Linda Lehman has strong links with Brazil and its National Leprosy Control Program where she served as advisor in her field of expertise for several years. -

LAST RITES of CHURCH ADMINISTERED Death- the Life : of the -Pontiff Is- Still in Rome." Stately and Venerable , Figures Hands Of-A Mob

A THE — Vote Early and Often for WEATHER: In St. .-. Paul and vicinity today: Queen of the Carnival ; Fair. THE ST. PAUL GLOBE. ft— : —— '\u25a0 MORNING} VOL. XXVI.—NO. 187. MONDAY JULY 6, 1903. PRICE TWO CENTS. ?I\,lr^T9. CMT IN GORGE, SCORES MEET BEATH FROM CLOUDBURST Flood Causes Breaking of Dam at Oakford Park, Pa., and BrßWrnM j^^***"£. <&yj:'*f*-'-.\u25a0 ¥ *\u25a0"' \u25a0 JK : _\\\^B*_B* fifr aJwrnw CKs^ffiS mwtSmrm u_m_w_W_\ t>^SSmim^LX^^^ .J*~ *Yft*> .f- * .V' ':^wß^Aw^Sawßt^SwmaW^-'^-w^F^^_W JtjLW*)**|JE^ «i. "^ S-^-yjßj Bfl^'"'?*. \u25a04* ' LJp Jrff4*"• '^^^B^^^^lh \u25a0*^^B[i^^^V^^Di!liE3i^i^^l9i^i^i^iK^Ssl^('M Many Drown Before They Can Reach Safety. • GREENSBURG. Pa., July; 5.—A waterspout of immense proportions striking in the vicinity of Oakford Park this afternoon at 6 o'clockcreated a flood v that caused c great, loss of life and : property. It is known that at least twenty .persons lost their lives, and rumors Iplace the number of dead at more than 100,. but until ''a late hour tonight only three or four, bodies have been, recovered, having been washed to the ".;banks of the " little creek that runs parallel with the park. 'The names of those known and -believed to have been drowned are: - " MISS GERTRUDE : .KEEFER, aged nineteen^'of .Jeannette.-i' .. EDWARD. O'BRIEN; of Latrobe. an employe ' of ,—Brown-Ketcham company, here.-"..-:':-^.':.'7/.-."~-7-. • PAPAL MASS- \u0084::7- f' JOSEPH j OVERLY,., of ' Indianapolis, IN ...i Ind., '\u25baemployed :by.;Brown:Ketcham. >T.-PCTER'S\ :ROMC \u25a0 FROM :i.'LULU3TRA2IONB -LUCY CRCM. -

Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time

!%JR:75()H QGV`(5( ( ! TwentyTwenty----NinthNinth Sunday in Ordinary Time Twenty-Ninth Sunday in Ordinary Time—October 21, 2018 Saint Andrew the Apostle Parish Page 2 Stewardship is a way of life. Today, October 21, 2018 Tithing is God’s Plan for Giving : World Mission Sunday October 7, 2018 CCD Classes Tithing Income $8,108.10 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School Tithe $ 810.81 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool $7,297.29 Online $ 752.00 R.C.I.A —Monday, October 22, 7:00—8:30pm, School Multipurpose Room Actual Income $8,049.29 Weekly Budget $7,500.00 Bible Study —Tuesday, October 23, 9:00—11:00 am and 6:30—8:30 pm both in the Parish Meeting Room. Poor Box $ 42.50 Next Weekend, October 27/28, 2018 Children’s Offerings $ 2.00 CCD Classes—Sunday 9:30-10:45am for Kindergarten—High School This week: 10/21: For the Family 10:50 thru 11am Mass for 3yr & 4yr Preschool of Garrett Seech, Christina Youth Group Soup Sales – after Masses in School hall Sentelle, Anna Marie Pickert; Kathaleen Bryan, Keith Wolfrey, Aliene Minister Schedule Misitis, Kellie Reiber, Philip Baker, Fred Eisenhart , Tom Lopresti, Frank Lago, If you are unable to serve, please find a substitute. Thank you. Adele Hanson, Gretchen Bertuccini , Chauney McGarney, Zoey Walker , Perry Saturday, October 27, 5pm: Fath, Lisa White, James J. Thomas, Cathy Kinman, Ed EMHC —Mike Geoffroy, Carmen Krawczak, Janet Bryner, Earl Bennett, Ty Long, Robin L. Fraley , Robin Stockton, 1 Needed ; Altar Servers —Ben Holderness, Gordon Fath, Jr., A Special Intention for Williams, Caiden -

Anointing of the Sick Catechesis

The Anointing of the Sick Adapted Bulletin Letters from Fr. Ed Fr. Edward L. Buelt Pastor Notre Dame Parish January 10 - February 1, 2021 My dear brothers and sisters in Christ, Anointing of the Sick is revealed in the Letter It is hard for me to believe that in June I of St. James. “Is anyone sick among you? He will be celebrate five years as the pastor of Notre should summon the presbyters of the church, Dame Parish. These years have been filled with and they should pray over him and anoint [him] many joys, but also challenges. with oil in the name of the Lord” (James 5:14). One of those challenges, actually, I have Over one thousand years later, in the borne for all 38 years of my priesthood, 1100s, the Bishop of Paris, Peter Lombard, although it is heightened in this pandemic. It became the first (it is believed) to use the term has to do with the celebration of the sacrament “extreme unction” to refer to this sacrament. of the Anointing of the Sick, specifically, the In the 1200s, St. Thomas Aquinas lack of knowledge regarding this sacrament. I explained that the term “extreme” referred to am frustrated that so many persons do not even those sicknesses “that bring man to the know there is a sacrament of the Anointing of extremity of his life” (Supplementum, Question the Sick, even though it has been around since 32, Article 3). He taught that “[the sacrament] Christ founded it almost 2,000 years ago. ought to be given to those only, who are so sick I am frustrated that so many believe as to be in a state of departure from this life, mistakenly that there is a sacrament called the through their sickness being of such a nature “last rites.” There has never been, nor is there as to cause death, the danger of which is to be now, a sacrament of the last rites. -

Respecting Creation Pope Francis’ New Encyclical Will Address the Moral Consequences of an Unequal Distribution of Resources, Waste, and the Exploitation of Nature

HAWAII FOURTH IN A SERIES WORLD WORLD Bishop expects a priest Comprehensive youth ‘The environment is God’s Vatican ready to announce at Kalaupapa for the ministry: empowering gift’: Church teaching on decision and guidelines ‘foreseeable future’ young people ecology before Pope Francis on Medjugorje Page 3 Page 7 Page 10-11 Page 13 HawaiiVOLUME 78, NUMBER 13 CatholicFRIDAY, JUNE 19, 2015 Herald$1 Respecting creation Pope Francis’ new encyclical will address the moral consequences of an unequal distribution of resources, waste, and the exploitation of nature By Barbara J. Fraser Catholic News Service LIMA, Peru — Pope Francis’ encyclical on ecology and climate, released this week, will send a strong moral message — one that could make some readers uncom- fortable, some observers say. “The encyclical will address the issue of inequality in the distribution of resources and topics such as the wasting of food and the irresponsible exploitation of na- ture and the consequences for people’s life and health,” Archbishop Pedro Barreto Jimeno of Huancayo, Peru, told Catholic News Service. “Pope Francis has repeatedly stated that the environ- ment is not only an economic or political issue, but is an anthropological and ethical matter,” he said. “How can you have wealth if it comes at the expense of the suffer- ing and death of other people and the deterioration of the environment?” The encyclical, published June 18, is titled “Laudato Si’: On the Care of Our Common Home,” which trans- lates “praised be,” the first words of St. Francis’ “Canticle