Written Evidence Submitted by Matthew Tong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russian Red in San Francisco SAN FRANCISCO

MUSIC Russian Red in San Francisco SAN FRANCISCO Thu, October 16, 2014 8:00 pm Venue The Independent, 628 Divisadero St, San Francisco, CA 94117 View map Phone: 415-771-1421 Admission Buy tickets. Doors open at 7:30 pm- More information Russian Red Credits The Spanish singer tours the U.S. and Canada to present her U.S. tour organized by The Windish third album ‘Agent Cooper.’ Agency, Charco and Sony Music Entertainment España S.L. Image courtesy of the artist. During the last few years Russian Red has become one of the most renowned artists in the Spanish music scene. Russian Red’s singer, Lourdes Hernández, has an exceptional voice and an innate ability to communicate and captivate a variety of audiences. She broke through the music scene in 2008 and became THE indie phenomenon with her debut album I Love Your Glasses (achieving a Gold record in Spain) and soon began performing on the main Spanish stages (Primavera Sound Festival, FIB, Jazzaldia, among many others), and reaching audiences in the USA, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Argentina, Costa Rica, Germany, Holland, Belgium, etc. In 2011 she released her second LP, Fuerteventura (with Sony Music) thus taking a big leap forward in her career. Produced by Tony Doogan (Belle & Sebastian, Mogwai, David Byrne, etc.) and recorded with Stevie Jackson, Bob Kildea and Richard Colburn from Belle & Sebastian, Fuerteventura debuted at #2 on the topselling albums charts in Spain, where it stood for over 39 weeks, consolidating her position as one of the most outstanding and international Spanish artists. Russian Red rounded the year off taking home the MTV EMA Award as “Best Spanish Artist.” Fuerteventura was not only a great success in Spain, but it also launched Russian Red onto the international scene, placing her in the international bands spectrum. -

Music Rights Specialists

Live Festival Recordings Promotional & Commercial Opportunities 1. Live Webcast Performances will be streamed through the at&t blue room (blueroom.att.com) with a prominent link directly from the festival website (www.lollapalooza.com - 3.3 million unique visitors / 16.1 million page views in 2006) ! 117,000 unique viewers of last year’s Lollaplaooza webcast ! During the performance, a link to your band’s website will be prominently featured in the blue room media player ! Past blue room participants include Dave Matthews Band, The Killers, Bjork, Depeche Mode, Tom Petty, Oasis, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Trey Anastasio, Bloc Party, Jack Johnson, The Pixies, Widespread Panic, My Morning Jacket, Franz Ferdinand, The Arcade Fire, Arctic Monkeys and many more ! at&t provides major online & radio promotion for the webcast – over 43 million impressions o Extensive online media buys on sites such as Real Networks, MP3.com, Jam Base, Pandora, Billboard, and more o Radio promo in major markets throughout the country Online feedback from fans who watched performances from previous Lollapalooza and Austin City Limits Music Festivals on the at&t blue room: “This is the best idea I have seen for a live music festival ever! I have already bought several CDs and songs based on the performances.” “Keep up the great work! It is amazing because you can hear SOOOO clearly and no noise, wind, screams, etc....It is the best streaming presentation I have ever seen. Upclose, clear and very very easy to use. It is perfect and plays no matter what other apps are running on the computer! I LOVE it! I'm looking forward to more, especially more performances next year at ACL music festival. -

Bloc Party Gets Intimate on New LP

---~~A~~F~S:~-~ -, --- PAGE6 .&.. · _ ___:--t_ · SEPTEMBER 2- 8 2008 The Expmdalb>les bring SFI showcases singing Sita reggae grooves to SS·U R<;>sEMCMACKIN 1930's. Her jazz and blues recordings StaffWriter give vibrant life and voice to Sita. Paley's animation style is wildly A'1ANDA CRAVER Prairie Sun Studios right here in Cotati. imaginative: the animated Sita resembles StaffWriter This versatile band combines punk rock, The colorfully animated "Sita Sings Betty Boop, the Sri Lankan king sports reggae, and 80's style guitar flare to cre the Blues," is the first feature-length of multiple heads, and Rama's skin is the ate a sound that fans just can't seem to fering from independent filmmaker Nina color of blue bells. Start the semester out with a bang get enough of. Paley, and it's making its Northern Cali Paley uses an abundance of vary and see what kind of entertainment No longer the rookies on the tour, fornia debut this week. ing visual styles, including several sty Sonoma State University is bringing The Expendables have accumulated a The Sonoma Film Institute will be listically rotoscoped sequences. The your way! rather large fan base of their own. Some screening Paley's unique vision of the psychedelic animation features a cast On Sept. 13, the Back to School of their most popular songs include "No "Ramayana" at Warren Auditorium in of hundreds, including flying monkeys, Concert in the Commons will feature Time to Worry," "One Night Stand," and Ives Hall. Screenings will be held on evil monsters, gods, goddesses, warriors, "24/7". -

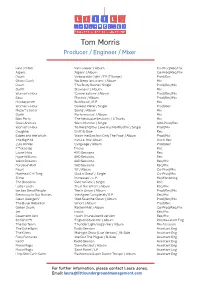

Tom Morris Producer / Engineer / Mixer

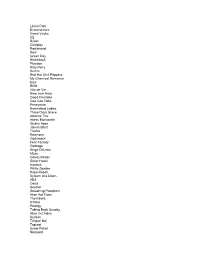

Tom Morris Producer / Engineer / Mixer Fear of Men ‘Fall Forever’ / Album Co-Prod/Rec/Mix Algiers ‘Algiers’ / Album Co-Prod/Rec/Mix Daunt ‘Unbearable Light’ / EP (2 Songs) Prod/Rec Ghost Outfit ‘No Sleep for Lovers’ / Album Mix Daunt ‘This Body Rushes’ Single Prod/Rec/Mix Outfit ‘Slowness’ / Album Mix Woman’s Hour ‘Conversations’ / Album Prod/Rec/Mix Eaux ‘Plastics’ / Album Prod/Rec/Mix Hockeysmith ‘But Blood’ / E.P. Mix Woman’s Hour ‘Darkest Place’ / Single Prod/Rec Mozart’s Sister ‘Being’ / Album Mix Outfit ‘Performance’ / Album Mix Bloc Party ‘The Nextwave Sessions’ / 3 Tracks Mix Glass Animals ‘Black Mambo’ / Single Add-Prod/Rec Woman’s Hour ‘To the End/Our Love Has No Rhythm’ / Single Prod/Mix Daughter ‘Drift’ B-Side Rec Esben and the Witch ‘Wash the Sins Not Only The Face’ / Album Prod/Mix The Big Pink ‘Future This’ Album Drum Rec Zulu Winter ‘Language’ / Album Prod/Rec F**cked Up Tracks Rec Laurel Halo 4AD Sessions Rec Hype Williams 4AD Sessions Rec Weird Dreams 4AD Sessions Rec/Mix Porcelain Raft 4AD Sessions Rec/Mix Faust ‘10’ / Album Co-Prod/Mix Matthew C H Tong ‘God is Great’ / Single Co-Prod/Mix Slime ‘Increases’ / E.P. Mix/Mastering The Breeders ‘Fate to Fatal’ / Single Rec Lydia Lunch ‘Trust the Witch’ / Album Rec/Mix Ice Sea Dead People ‘Teeth Union’ / Album Prod/Rec/Mix Electricity In Our Homes ‘We Agree Completely’ E.P. Rec/Mix Clean George IV ‘God Save the Clean’ / Album Prod/Rec/Mix The Boxer Rebellion ‘Union’ / Album Prod/Rec Gallon Drunk ‘Rotten Mile’ / Album Co-Prod/Rec/Mix Jet Tracks Rec/Mix Basement Jaxx ‘Hush’ -

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay

Linkin Park Evanescence Vama Veche U2 Byron Coldplay Radiohead Korn Green Day Nickelback Placebo Katy Perry Kumm Red Hot Chili Peppers My Chemical Romance Eels REM Vita de Vie Nine Inch Nails Good Charlotte Goo Goo Dolls Pennywise Barenaked Ladies Three Days Grace Alkaline Trio Alanis Morissette Guano Apes James Blunt Travka Reamonn Godsmack Fear Factory Garbage Kings Of Leon Muse Gandul Matei Sister Hazel Incubus White Zombie Papa Roach System of a Down AB4 Oasis Seether Smashing Pumpkins Alien Ant Farm The Killers Ill Nino Prodigy Taking Back Sunday Alice in Chains Kutless Timpuri Noi Taproot Snow Patrol Nonpoint Dashboard Confessional The Cure The Cranberries Stereophonics Blink 182 Phish Blur Rage Against the Machine Gorillaz Pulp Bowling For Soup Citizen Cope Manic Street Preachers Luna Amara Nirvana The Verve Breaking Benjamin Chevelle Modest Mouse Jeff Buckley Beck Arctic Monkeys Bloodhound Gang Sevendust Coma Lostprophets Keane Blue October 30 Seconds to Mars Suede Collective Soul Kill Hannah Foo Fighters The Cult Feeder Veruca Salt Skunk Anansie 3 Doors Down Deftones Sugar Ray Counting Crows Mushroomhead Electric Six Filter Lynyrd Skynyrd Biffy Clyro Death Cab For Cutie Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds The White Stripes James Morrison Texas Crazy Town Mudvayne Placebo Crash Test Dummies Poets Of The Fall Jason Mraz Linkin Park Sum 41 Grimus Guster A Perfect Circle Tool The Strokes Flyleaf Chris Cornell Smile Empty Soul Audioslave Nirvana Gogol Bordello Bloc Party Thousand Foot Krutch Brand New Razorlight Puddle Of Mudd Sonic Youth -

Bloc Party-Time Dave Robinson Is the New Kid at the Bloc, a Three-Day Festival of Electronic Music in the West Country

PSNE May P23-35 Live 5/5/11 12:46 Page 29 May 2011 G www.prosoundnewseurope.com live 29 WORLD Bloc party-time Dave Robinson is the new kid at the Bloc, a three-day festival of electronic music in the West Country Earthquake bass. Concrete beats. Bleeps and blarps and Kevin Martin, AKA King Midas Sound, shakes Red:Bloc f blips. And a bodyslam or two of dubstep. Where are we, some deso- crew have hosted their acclaimed Ableton RFID (Recursive Function late industrial estate on the periphery indie weekenders at the site. Immersive Dome). “I have a Logic of Berlin? Er, no. Butlins. For the last three years, it has been System, I’m a big fan of the old stuff, For one weekend in early spring – home to Bloc, a festival that delivers an because I’m a one-man operation so I in Butlins, Minehead, Somerset – it’s increasingly impressive line-up of elec- needed stuff I could move around,” says electronica central. tronic acts, old and new. But this is no Kirkby. He’s been involved with Bristol’s Before the pallid masses from the Creamfields, it’s a little more ‘chin- dance scene, particularly dubstep, for a Midlands descend on the quiet coastal strokey’ than that. A little more leftfield while. His spec for the RFID – where region for a summer of Factor 50- and eclectic. This year’s line-up included punters are encouraged to try out DJing based fun, Butlins fulfils another LFO, FourTet, Speedy J, Vitalic, and a gear supplied by Serato/Ableton/ brief, you see, and that is as a venue double-headline of Aphex Twin and Novation includes “four 18” subs, four for, well, whoever wants to hire it. -

Playnetwork Business Mixes

PlayNetwork Business Mixes 50s to Early 60s Marketing Strategy: Period themes, burgers and brews and pizza, bars, happy hour Era: Classic Compatible Music Styles: Fun-Time Oldies, Classic Description: All tempos and styles that had hits Rock, 70s Mix during the heyday of the 50s and into the early 60s, including some country as well Representative Artists: Elvis, Fats Domino, Steve 70s Mix Lawrence, Brenda Lee, Dinah Washington, Frankie Era: 70s Valli and the Four Seasons, Chubby Checker, The Impressions Description: An 8-track flashback of great music Appeal: People who can remember and appreciate from the 70s designed to inspire memories for the major musical moments from this era everyone. Featuring hits and historically significant album cuts from the “Far Out!,” Bob Newhart, Sanford Feel: All tempos and Son era Marketing Strategy: Hamburger/soda fountain– Representative Artists: The Eagles, Elton John, themed cafes, period-themed establishments, bars, Stevie Wonder, Jackson Brown, Gerry Rafferty, pizza establishments and clothing stores Chicago, Doobie Brothers, Brothers Johnson, Alan Parsons Project, Jim Croce, Joni Mitchell, Sugarloaf, Compatible Music Styles: Jukebox classics, Donut Steely Dan, Earth Wind & Fire, Paul Simon, Crosby, House Jukebox, Fun-Time Oldies, Innocent 40s, 50s, Stills, and Nash, Creedence Clearwater Revival, 60s Average White Band, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, Electric Light Orchestra, Fleetwood Mac, Guess Who, 60s to Early 70s Billy Joel, Jefferson Starship, Steve Miller Band, Carly Simon, KC & the Sunshine Band, Van Morrison Era: Classic Feel: A warm blanket of familiar music that helped Description: Good-time pop and rock legends from define the analog sound of the 70s—including the the mid-60s through the early-to-mid-70s that marked one-hit wonders and the best known singer- the end of an era. -

Lyric Hammersmith Press Release

PRESS RELEASE 04 September 2019 LYRIC HAMMERSMITH SPRING 2019 SEASON ANNOUNCEMENT Today the Lyric Hammersmith announces its Spring 2019 season, the final productions programmed by outgoing Artistic Director Sean Holmes. The season celebrates Holmes’ tenure - bringing back one of his most successful shows, reflecting the Lyric’s partnerships with the UK’s leading theatre companies, and embodying a reputation for daring new work alongside a commitment to nurturing the creativity of young people. Leave to Remain – the world premiere of a new play with songs by Matt Jones and Kele Okereke opens the season. Commissioned by the Lyric, directed by Robby Graham and designed by Rebecca Brower, with Olivier Award nominated actor Tyrone Huntley in the lead role. The first song from Leave to Remain, ‘Not the drugs talking’ written and performed by Bloc Party’s Kele Okereke is released today, available on iTunes and Spotify. The Lyric welcomes the highly acclaimed 1927 Theatre Company with The Animals and Children Took to the Streets and Kneehigh’s Dead Dog in a Suitcase (and other love songs). Ghost Stories – following worldwide success and the smash hit movie, the original terrifying hit is back. Written by Andy Nyman and Jeremy Dyson and directed by Andy Nyman, Jeremy Dyson and Sean Holmes. Continuing the theatre’s commitment to providing opportunities for young creative talent, Holly Race Roughan is announced as the Artistic Director for the Lyric Ensemble for 2019 and TD Moyo as the director for the lead show of the Evolution Festival. A new season of Little Lyric shows is announced for families and children under 11, presented in the newly refurbished studio theatre. -

Does NME Even Know What a Music Blog Is?

Does NME even know what a music blog is?: The Rhetoric and Social Meaning of MP3 Blogs by Larissa Wodtke A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English - Rhetoric and Communication Design Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2008 © Larissa Wodtke 2008 Author‘s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract MP3 blogs and their aggregators, which have risen to prominence over the past four years, are presenting an alternative way of promoting and discovering new music. I will argue that MP3 files greatly affect MP3 blogs in terms of shaping them as: a genre separate from general weblogs and music blogs without MP3s, especially due to the impact of MP3 blog aggregators such as The Hype Machine and Elbows; a particular form of rhetoric illuminated by Kenneth Burke's dramatistic ratios of agency-purpose, purpose-act and scene-act; and as a potentially subversive subculture, which like other subcultures, exists in a symbiotic relationship with the traditional media it defines itself against. Using excerpts from multiple MP3 blogs and their forums, interviews with MP3 bloggers and Anthony Volodkin (creator of The Hype Machine), references to MP3 blogs in traditional press, and Burke's theory of dramatism and Hodge and Kress's theories of social semiotics, I will demonstrate that the MP3 file is not only changing the way music is consumed and circulated, but also the way music is promoted and discussed. -

The Love Within PR

BLOC PARTY. “THE LOVE WITHIN” Bloc Party today premiere their eagerly anticipated new song “The Love Within,” available to stream now via Infectious Music/BMG /Vagrant Records. “The Love Within” is a first taste from Bloc Party’s forthcoming, as-yet-untitled fifth album, due for release in early 2016. Listen to “The Love Within”: https://soundcloud.com/blocparty/bloc-party-the-love-within Earlier today Bloc Party performed at London’s prestigious Maida Vale studios to open BBC 6 Music Live, a weeklong series of live music broadcast from the BBC. The band’s set included new songs “The Good News” and “Exes” alongside highlights from their critically lauded back catalogue including “Octopus” (from 2012’s Four), “Banquet” (from 2005’s Silent Alarm), and “This Modern Love” (also from Silent Alarm). In August, Bloc Party made their live return in America, playing two sold out shows on the West Coast before an acclaimed appearance at this year’s FYF Fest, where they headlined The Lawn stage. They are confirmed to headline Falls Festival in Australia this winter, and play a run of intimate European shows in November-December; see www.bloc.party for details: 27 November - Paradiso, Amsterdam, NL - SOLD OUT 28 November - Live Music Hall, Koln, DE 29 November - Astra Kulturhaus, Berlin, DE - SOLD OUT 01 December - Alhambra, Paris, FR - SOLD OUT 02 December - Cirque Royal, Brussels, BL - SOLD OUT 03 December - Albert Hall, Manchester, UK - SOLD OUT 04 December - St John at Hackney, London, UK - SOLD OUT Bloc Party are: Kele Okereke (vocals, guitar), Russell Lissack (guitar), Justin Harris (bass) and Louise Bartle (drums). -

Ecological Models of Musical Structure in Pop-Rock, 1950–2019

Ecological Models of Musical Structure in Pop-rock, 1950–2019 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas J. Shea, M.A., B.Ed. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee: Anna Gawboy, Advisor and Dissertation Co-Advisor Nicole Biamonte, Dissertation Co-Advisor Daniel Shanahan David Clampitt Copyright by Nicholas J. Shea 2020 Abstract This dissertation explores the relationship between guitar performance and the functional components of musical organization in popular-music songs from 1954 to 2019. Under an ecological theory of affordances, three distinct interdisciplinary approaches are employed: empirical analyses of two stylistically contrasting databases of popular-music song transcriptions, a motion-capture study of performances by practicing musicians local to Columbus, Ohio, and close readings of works performed and/or composed by popular- music guitarists. Each offers gestural analyses that provide an alternative to the object- oriented approach of standard popular-music analysis, as well as clarification on issues related to style, such as the socially determined differences between “pop” and “rock” music. ii Dedication To Anna Gawboy, who is always in my corner. iii Acknowledgments Here I face the nearly insurmountable task of thanking those who have helped to develop this research. Even as all written and analytical content in this document is my own, I cannot deny the incredible value collaboration has brought to this inherently interdisciplinary study. I am extremely fortunate to have a small team of individuals on which I can rely for mentorship and support and whose research backgrounds contribute greatly to the domains of this document. -

The Mixtape Extended Setlist 2017

SET LIST SONG ARTIST Rebellion (Lies) Arcade Fire Keep the car running Arcade Fire Intervention Arcade Fire Ready to Start Arcade Fire I bet you look good on the dancefloor Arctic Monkeys Do I wanna know? Arctic Monkeys Shining Light Ash Pompeii Bastille St. Andrews Bedouin Soundclash Eve, the apple of my eye Bell X1 Catch My Disease Ben Lee Crazy in Love Beyonce & Jay Z Hyperballad Bjork All the small things Blink 182 I miss you Blink 182 Banquet Bloc Party The Prayer Bloc Party Uniform Bloc Party Positive Tension Bloc Party Hanging on the Telephone Blondie Girls & Boys Blur The Universal Blur Song 2 Blur All Along the Watchtower Bob Dylan Knocking on Heaven’s Door Bob Dylan Lay Lady Lay Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone Bob Dylan Shelter From the Storm Bob Dylan Times are a changing Bob Dylan Livin on a prayer Bon Jovi Dead or Alive Bon Jovi More Than A Feeling Boston There is Box Car Racer Soco Amaretto Lime Brand New The quiet things that no one ever knows Brand New Jesus Brand New You Won't Know Brand New Okay I believe you... Brand New Not the sun Brand New You Stole Brand New Anthems for a 17 year old girl Broken Social Scene Cat’s in the cradle Cat Stevens Wicked Game Chris Isaac Cocaine Eric Clapton Layla Eric Clapton Old Love Eric Clapton White Room Eric Clapton Sunshine of your Love Eric Clapton Badge Eric Clapton Don’t Panic Coldplay Fix You Coldplay Shiver Coldplay The Scientist Coldplay Yellow Coldplay Viva La Vida Coldplay Charlie Brown Coldplay A Real Hero College & Electric Youth Zombie Cranberries Everywhere you go Crowded