Aggravated with Aggregators: Can International Copyright Law Help Save the News Room?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Find the Best Hashtags for Your Business Hashtags Are a Simple Way to Boost Your Traffic and Target Specific Online Communities

CHECKLIST How to find the best hashtags for your business Hashtags are a simple way to boost your traffic and target specific online communities. This checklist will show you everything you need to know— from the best research tools to tactics for each social media network. What is a hashtag? A hashtag is keyword or phrase (without spaces) that contains the # symbol. Marketers tend to use hashtags to either join a conversation around a particular topic (such as #veganhealthchat) or create a branded community (such as Herschel’s #WellTravelled). HOW TO FIND THE BEST HASHTAGS FOR YOUR BUSINESS 1 WAYS TO USE 3 HASHTAGS 1. Find a specific audience Need to reach lawyers interested in tech? Or music lovers chatting about their favorite stereo gear? Hashtags are a simple way to find and reach niche audiences. 2. Ride a trend From discovering soon-to-be viral videos to inspiring social movements, hashtags can quickly connect your brand to new customers. Use hashtags to discover trending cultural moments. 3. Track results It’s easy to monitor hashtags across multiple social channels. From live events to new brand campaigns, hashtags both boost engagement and simplify your reporting. HOW TO FIND THE BEST HASHTAGS FOR YOUR BUSINESS 2 HOW HASHTAGS WORK ON EACH SOCIAL NETWORK Twitter Hashtags are an essential way to categorize content on Twitter. Users will often follow and discover new brands via hashtags. Try to limit to two or three. Instagram Hashtags are used to build communities and help users find topics they care about. For example, the popular NYC designer Jessica Walsh hosts a weekly Q&A session tagged #jessicasamamondays. -

Groupwise Mobility Quick Start for Microsoft Outlook Users

GroupWise Mobility Quick Start for Microsoft Outlook Users August 2016 GroupWise Mobility Service 2014 R2 allows the Microsoft Outlook client for Windows to run against a GroupWise backend via Microsoft ActiveSync 14.1 protocol. This document helps you set up your Outlook client to access your GroupWise account and provides known limitations you should be aware of while using Outlook against GroupWise. Supported Microsoft Outlook Clients CREATING THE GROUPWISE PROFILE MANUALLY Microsoft Outlook 2013 or 21016 for Windows 1 On the machine, open Control Panel > User Accounts and Family Safety. Microsoft Outlook Mobile App Adding a GroupWise Account to the Microsoft Outlook Client You must configure the Microsoft Outlook client in order to access your GroupWise account. The following instructions assume that the Outlook client is already installed on your machine. You can use the GroupWise Profile Setup utility to set the profile up automatically or you can manually create the GroupWise profile for Outlook. Using the GroupWise Profile Setup Utility Creating the GroupWise Profile Manually 2 Click Mail. 3 (Conditional) If a Mail Setup dialog box is displayed, USING THE GROUPWISE PROFILE SETUP UTILITY click Show Profiles to display the Mail dialog box. You must first obtain a copy of the GWProfileSetup.zip from If GroupWise is installed on the machine, the Profiles your system administrator before following the steps below list includes a GroupWise profile, as shown in the to create the profile on your workstation. following screenshot. You need to keep this profile and create a new profile. 1 Extract the GWProfileSetup.zip to a temporary location on your workstation. -

Virtual Planetary Space Weather Services Offered by the Europlanet H2020 Research Infrastructure

Article PSS PSWS deadline 15/11 Virtual Planetary Space Weather Services offered by the Europlanet H2020 Research Infrastructure N. André1, M. Grande2, N. Achilleos3, M. Barthélémy4, M. Bouchemit1, K. Benson3, P.-L. Blelly1, E. Budnik1, S. Caussarieu5, B. Cecconi6, T. Cook2, V. Génot1, P. Guio3, A. Goutenoir1, B. Grison7, R. Hueso8, M. Indurain1, G. H. Jones9,10, J. Lilensten4, A. Marchaudon1, D. Matthiäe11, A. Opitz12, A. Rouillard1, I. Stanislawska13, J. Soucek7, C. Tao14, L. Tomasik13, J. Vaubaillon6 1Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie, CNRS, Université Paul Sabatier, Toulouse, France ([email protected]) 2Department of Physics, Aberystwyth University, Wales, UK 3University College London, London, UK 4Institut de Planétologie et d'Astrophysique de Grenoble, UGA/CNRS-INSU, Grenoble, France 5GFI Informatique, Toulouse, France 6LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC, University Paris Diderot, Meudon, France 7Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Czech Academy of Science, Prague, Czech Republic 8Departamento de Física Aplicada I, Escuela de Ingeniería de Bilbao, Universidad del País Vasco UPV /EHU, Bilbao, Spain 9Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, Holmbury Saint Mary, UK 10The Centre for Planetary Sciences at UCL/Birkbeck, London, UK 11German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Aerospace Medicine, Linder Höhe, 51147 Cologne, Germany 12Wigner Research Centre for Physics, Budapest, Hungary 13Space Research Centre, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland 14National Institute of Information -

Netscape 6.2.3 Software for Solaris Operating Environment

What’s New in Netscape 6.2 Netscape 6.2 builds on the successful release of Netscape 6.1 and allows you to do more online with power, efficiency and safety. New is this release are: Support for the latest operating systems ¨ BETTER INTEGRATION WITH WINDOWS XP q Netscape 6.2 is now only one click away within the Windows XP Start menu if you choose Netscape as your default browser and mail applications. Also, you can view the number of incoming email messages you have from your Windows XP login screen. ¨ FULL SUPPORT FOR MACINTOSH OS X Other enhancements Netscape 6.2 offers a more seamless experience between Netscape Mail and other applications on the Windows platform. For example, you can now easily send documents from within Microsoft Word, Excel or Power Point without leaving that application. Simply choose File, “Send To” to invoke the Netscape Mail client to send the document. What follows is a more comprehensive list of the enhancements delivered in Netscape 6.1 CONFIDENTIAL UNTIL AUGUST 8, 2001 Netscape 6.1 Highlights PR Contact: Catherine Corre – (650) 937-4046 CONFIDENTIAL UNTIL AUGUST 8, 2001 Netscape Communications Corporation ("Netscape") and its licensors retain all ownership rights to this document (the "Document"). Use of the Document is governed by applicable copyright law. Netscape may revise this Document from time to time without notice. THIS DOCUMENT IS PROVIDED "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND. IN NO EVENT SHALL NETSCAPE BE LIABLE FOR INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OF ANY KIND ARISING FROM ANY ERROR IN THIS DOCUMENT, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION ANY LOSS OR INTERRUPTION OF BUSINESS, PROFITS, USE OR DATA. -

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: a Review and Framework

Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework Item Type Journal Article (On-line/Unpaginated) Authors Trant, Jennifer Citation Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework 2009-01, 10(1) Journal of Digital Information Journal Journal of Digital Information Download date 02/10/2021 03:25:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/105375 Trant, Jennifer (2009) Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework. Journal of Digital Information 10(1). Studying Social Tagging and Folksonomy: A Review and Framework J. Trant, University of Toronto / Archives & Museum Informatics 158 Lee Ave, Toronto, ON Canada M4E 2P3 jtrant [at] archimuse.com Abstract This paper reviews research into social tagging and folksonomy (as reflected in about 180 sources published through December 2007). Methods of researching the contribution of social tagging and folksonomy are described, and outstanding research questions are presented. This is a new area of research, where theoretical perspectives and relevant research methods are only now being defined. This paper provides a framework for the study of folksonomy, tagging and social tagging systems. Three broad approaches are identified, focusing first, on the folksonomy itself (and the role of tags in indexing and retrieval); secondly, on tagging (and the behaviour of users); and thirdly, on the nature of social tagging systems (as socio-technical frameworks). Keywords: Social tagging, folksonomy, tagging, literature review, research review 1. Introduction User-generated keywords – tags – have been suggested as a lightweight way of enhancing descriptions of on-line information resources, and improving their access through broader indexing. “Social Tagging” refers to the practice of publicly labeling or categorizing resources in a shared, on-line environment. -

Guide to Customizing and Distributing Netscape 7.0

Guide to Customizing and Distributing Netscape 7.0 28 August 2002 Copyright © 2002 Netscape Communications Corporation. All rights reserved. Netscape and the Netscape N logo are registered trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation in the U.S. and other countries. Other Netscape logos, product names, and service names are also trademarks of Netscape Communications Corporation, which may be registered in other countries. The product described in this document is distributed under licenses restricting its use, copying, distribution, and decompilation. No part of the product or this document may be reproduced in any form by any means without prior written authorization of Netscape and its licensors, if any. THIS DOCUMENTATION IS PROVIDED “AS IS” AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED CONDITIONS, REPRESENTATIONS AND WARRANTIES, INCLUDING ANY IMPLIED WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE OR NON-INFRINGEMENT, ARE DISCLAIMED, EXCEPT TO THE EXTENT THAT SUCH DISCLAIMERS ARE HELD TO BE LEGALLY INVALID. Contents Preface . 9 Who Should Read This Guide . 10 About the CCK Tool . 10 If You've Used a Previous Version of CCK . 11 Using Existing Customized Files . 12 How to Use This Guide . 13 Where to Go for Related Information . 15 Chapter 1 Getting Started . 17 Why Customize and Distribute Netscape? . 18 Why Do Users Prefer Netscape 7.0? . 18 Overview of the Customization and Distribution Process . 20 System Requirements . 23 Platform Support . 25 Installing the Client Customization Kit Tool . 26 What Customizations Can I Make? . 27 Netscape Navigator Customizations . 27 Mail and News Customizations . 32 CD Autorun Screen Customizations . 32 Installer Customizations . 33 Customization Services Options . 34 Which Customizations Can I Make Quickly? . -

Acceptable Use of Instant Messaging Issued by the CTO

State of West Virginia Office of Technology Policy: Acceptable Use of Instant Messaging Issued by the CTO Policy No: WVOT-PO1010 Issued: 11/24/2009 Revised: 12/22/2020 Page 1 of 4 1.0 PURPOSE This policy details the use of State-approved instant messaging (IM) systems and is intended to: • Describe the limitations of the use of this technology; • Discuss protection of State information; • Describe privacy considerations when using the IM system; and • Outline the applicable rules applied when using the State-provided system. This document is not all-inclusive and the WVOT has the authority and discretion to appropriately address any unacceptable behavior and/or practice not specifically mentioned herein. 2.0 SCOPE This policy applies to all employees within the Executive Branch using the State-approved IM systems, unless classified as “exempt” in West Virginia Code Section 5A-6-8, “Exemptions.” The State’s users are expected to be familiar with and to comply with this policy, and are also required to use their common sense and exercise their good judgment while using Instant Messaging services. 3.0 POLICY 3.1 State-provided IM is appropriate for informal business use only. Examples of this include, but may not be limited to the following: 3.1.1 When “real time” questions, interactions, and clarification are needed; 3.1.2 For immediate response; 3.1.3 For brainstorming sessions among groups; 3.1.4 To reduce chances of misunderstanding; 3.1.5 To reduce the need for telephone and “email tag.” 3.2 Employees must only use State-approved instant messaging. -

Geotagging Photos to Share Field Trips with the World During the Past Few

Geotagging photos to share field trips with the world During the past few years, numerous new online tools for collaboration and community building have emerged, providing web-users with a tremendous capability to connect with and share a variety of resources. Coupled with this new technology is the ability to ‘geo-tag’ photos, i.e. give a digital photo a unique spatial location anywhere on the surface of the earth. More precisely geo-tagging is the process of adding geo-spatial identification or ‘metadata’ to various media such as websites, RSS feeds, or images. This data usually consists of latitude and longitude coordinates, though it can also include altitude and place names as well. Therefore adding geo-tags to photographs means adding details as to where as well as when they were taken. Geo-tagging didn’t really used to be an easy thing to do, but now even adding GPS data to Google Earth is fairly straightforward. The basics Creating geo-tagged images is quite straightforward and there are various types of software or websites that will help you ‘tag’ the photos (this is discussed later in the article). In essence, all you need to do is select a photo or group of photos, choose the "Place on map" command (or similar). Most programs will then prompt for an address or postcode. Alternatively a GPS device can be used to store ‘way points’ which represent coordinates of where images were taken. Some of the newest phones (Nokia N96 and i- Phone for instance) have automatic geo-tagging capabilities. These devices automatically add latitude and longitude metadata to the existing EXIF file which is already holds information about the picture such as camera, date, aperture settings etc. -

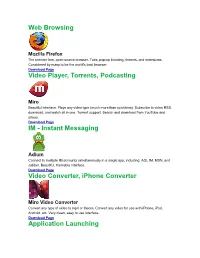

Instant Messaging Video Converter, Iphone Converter Application

Web Browsing Mozilla Firefox The premier free, open-source browser. Tabs, pop-up blocking, themes, and extensions. Considered by many to be the world's best browser. Download Page Video Player, Torrents, Podcasting Miro Beautiful interface. Plays any video type (much more than quicktime). Subscribe to video RSS, download, and watch all in one. Torrent support. Search and download from YouTube and others. Download Page IM - Instant Messaging Adium Connect to multiple IM accounts simultaneously in a single app, including: AOL IM, MSN, and Jabber. Beautiful, themable interface. Download Page Video Converter, iPhone Converter Miro Video Converter Convert any type of video to mp4 or theora. Convert any video for use with iPhone, iPod, Android, etc. Very clean, easy to use interface. Download Page Application Launching Quicksilver Quicksilver lets you start applications (and do just about everything) with a few quick taps of your fingers. Warning: start using Quicksilver and you won't be able to imagine using a Mac without it. Download Page Email Mozilla Thunderbird Powerful spam filtering, solid interface, and all the features you need. Download Page Utilities The Unarchiver Uncompress RAR, 7zip, tar, and bz2 files on your Mac. Many new Mac users will be puzzled the first time they download a RAR file. Do them a favor and download UnRarX for them! Download Page DVD Ripping Handbrake DVD ripper and MPEG-4 / H.264 encoding. Very simple to use. Download Page RSS Vienna Very nice, native RSS client. Download Page RSSOwl Solid cross-platform RSS client. Download Page Peer-to-Peer Filesharing Cabos A simple, easy to use filesharing program. -

Development of Information System for Aggregation and Ranking of News Taking Into Account the User Needs

Development of Information System for Aggregation and Ranking of News Taking into Account the User Needs Vasyl Andrunyk[0000-0003-0697-7384]1, Andrii Vasevych[0000-0003-4338-107X]2, Liliya Chyrun[0000-0003-4040-7588]3, Nadija Chernovol[0000-0001-9921-9077]4, Nataliya Antonyuk[0000- 0002-6297-0737]5, Aleksandr Gozhyj[0000-0002-3517-580X]6, Victor Gozhyj7, Irina Kalinina[0000- 0001-8359-2045]8, Maksym Korobchynskyi[0000-0001-8049-4730]9 1-4Lviv Polytechnic National University, Lviv, Ukraine 5Ivan Franko National University of Lviv, Lviv, Ukraine 5University of Opole, Opole, Poland 6-8Petro Mohyla Black Sea National University, Nikolaev, Ukraine 9Military-Diplomatic Academy named after Eugene Bereznyak, Kyiv, Ukraine [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract. The purpose of the work is to develop an intelligent information sys- tem that is designed for aggregation and ranking of news taking into account the needs of the user. During the work, the following tasks are set: 1) Analyze the online market for mass media and the needs of readers; the pur- pose of their searches and moments is not enough to find the news. 2) To construct a conceptual model of the information aggression system and ranking of news that would enable presentation of the work of the future intel- lectual information system, to show its structure. 3) To select the methods and means for implementation of the intellectual in- formation system. -

Web Browser Set-Up Guide for New BARC

Web Browser Set-up Guide for new BARC The new BARC system is web-based and is designed to work best with Netscape 4.79. Use the chart below to determine the appropriate set-up for your web browser to use new BARC. What type of computer do you use? What you will need to do in order to use the new BARC system… I am a Thin Client user. You do not need to do anything. The version of Netscape available to Thin Client users (version 4.75) will work with the new BARC system. I use a PC and the following statement about the Netscape web browser applies to my workstation…. I don’t have Netscape. Proceed to Section 2 of this document for instructions on how you can download and install Netscape 4.79. I only have Netscape 6.x or Netscape 7.x. Proceed to Section 2 of this document for instructions on how you can download and install Netscape 4.79. I currently have Netscape 4.79. You do not need to do anything. The new BARC system was designed to work best with the version of Netscape you have. I currently have Netscape 4.75 or Netscape 4.76. You do not need to do anything. Even though the new BARC system is designed to work best in Netscape 4.79, the application will work fine with Netscape 4.75 and Netscape 4.76. I have a version of Netscape 4, but it is not Proceed to Section 1 of this document Netscape 4.75, Netscape 4.76 or Netscape 4.79 and to uninstall the current version of I have an alternative web browser (such as Microsoft Netscape you have and then continue Internet Explorer, Netscape 6.x or Netscape 7.x) on to Section 2 to download and on my workstation. -

Tag Recommendations in Social Bookmarking Systems

1 Tag Recommendations in Social Bookmarking Systems Robert Jaschke¨ a,c Leandro Marinho b,d 1. Introduction Andreas Hotho a Lars Schmidt-Thieme b Gerd Stumme a,c Folksonomies are web-based systems that allow users to upload their resources, and to label them with a Knowledge & Data Engineering Group (KDE), arbitrary words, so-called tags. The systems can be dis- University of Kassel, tinguished according to what kind of resources are sup- 1 Wilhelmshoher¨ Allee 73, 34121 Kassel, Germany ported. Flickr , for instance, allows the sharing of pho- tos, del.icio.us2 the sharing of bookmarks, CiteULike3 http://www.kde.cs.uni-kassel.de 4 b and Connotea the sharing of bibliographic references, Information Systems and Machine Learning Lab and last.fm5 the sharing of music listening habits. Bib- (ISMLL), University of Hildesheim, 6 Sonomy allows to share bookmarks and BIBTEX based Samelsonplatz 1, 31141 Hildesheim, Germany publication entries simultaneously. http://www.ismll.uni-hildesheim.de In their core, these systems are all very similar. Once c Research Center L3S, a user is logged in, he can add a resource to the sys- Appelstr. 9a, 30167 Hannover, Germany tem, and assign arbitrary tags to it. The collection of all his assignments is his personomy, the collection of http://www.l3s.de folksonomy d all personomies constitutes the . The user Brazilian National Council Scientific and can explore his personomy, as well as the whole folk- Technological Research (CNPq) scholarship holder. sonomy, in all dimensions: for a given user one can see all resources he has uploaded, together with the tags he Abstract.