Lower Fall Creek Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parks & Green Spaces Within the I-465 Ring

Parks & Green Spaces within the I-465 ring Blickman Educational Trail Park (6399 N. Meridian St.) Broad Ripple Park (1500 Broad Ripple Ave.) 62 acres Fall Creek & 30th Park (2925 E Fall Creek Pkwy N Dr.) - borders the Fall Creek Parkway Trail Franklin Township Community Park (8801 E Edgewood Ave.) Glenns Valley Nature Park (8015 Bluffs Rd.) Holliday Park (6349 Springmill Rd.) 94 acres Juan Solomon Park (6100 Grandview Dr.) 41 acres Northwestway Park (5253 W 62nd St.) Paul Ruster Park (11300 E Prospect St.) 82 acres Raymond Park (8300 Raymond St.) 35 acres Skiles Test Nature Park (6828 Fall Creek Rd.) Town Run Trail Park South (5325 E 96th St.) 127 acres - bikers have right-of-way; hike with extreme caution Washington Park (3130 E 30th St.) 128 acres Lilly ARBOR (adjacent to IUPUI campus, located along the White River on Porto Alegre St. between 10th St. bridge and New York St. bridge; park in lot 63 and take stairs at New York St. down to the trail) Parks & Green Spaces outside the I-465 ring North (Boone & Hamilton Counties) Central Park (1235 Central Park Dr. E, Carmel) 159 acres Cheeney Creek Natural Area (11030 Fishers Pointe Blvd., Fishers) 25 acres Cool Creek Park (2000 E 151st St, Carmel) 90 acres Creekside Nature Park (11001 Sycamore St., Zionsville) 18 acres - parking limited; park across the street at Lions Park and take the trail under the bridge to Creekside Creekside Corporate Park (W 106th St., Zionsville) 24 acres - links to Creekside Nature Park via bridge across Eagle Creek along S main St./Zionsville Rd Hoosier Woods -

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail

Reasons to Love the Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn Glick The Indianapolis Cultural Trail: A Legacy of Gene and Marilyn The Indianapolis Cultural Trail is having a Glick (the Trail) is an eight-mile urban bike and pedestrian measurable economic impact. pathway that serves as a linear park in the core of downtown Property values within 500 feet (approximately one block) Indianapolis. Originally conceived by Brian Payne, Presi- of the Trail have increased 148% from 2008 to 2014, an dent and CEO of the Central Indiana Community Foundation increase of $1 billion in assessed property value. (CICF), to help create and spur development in the city’s cultural districts, the Trail provides a beautiful connection for residents and visitors to safely explore downtown. Com- many businesses along Massachusetts and Virginia Avenues.The Trail Businesshas increased surveys revenue reported and part-timecustomer andtraffic full-time for cultural districts and provides a connection to the seventh via jobs have been added due to the increases in revenue and pleted in 2012, the Trail connects the now six (originally five) - tural, heritage, sports, and entertainment venue in downtown Indianapolisthe Monon Trail. as well The as Trail vibrant connects downtown every significantneighborhoods. arts, cul customers in just the first year. It also serves as the downtown hub for the central Indiana expenditure for all users is $53, and for users from outside greenway system. theUsers Indianapolis are spending area while the averageon the Trail. exceeds The $100.average In all,expected Trail users contributed millions of dollars in local spending. -

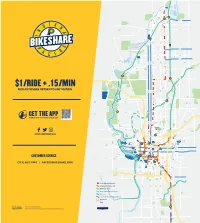

Get Theapp Mobile Map and Bikecheck out Customer Service @Pacersbikeshare | Pacersbikeshare.Org 0

E 71ST ST. Marott Park Indianapolis Art Center Opti Park 66TH ST. RIVERVIEW DR. WESTFIELD BLVD. N MERIDIAN ST. 65TH ST. er 64TH ST. v White Ri WASHINGTON BLVD. CENTRAL AVE. Holliday Park White Rive Broad Ripple Park r BROAD RIPPLE AVE. WINTHROP AVE. WINTHROP GUILFORD AVE. GUILFORD COLLEGE AVE. BROAD RIPPLE AVE. RIVERVIEW DR. E 63RD ST. WESTFIELD BLVD. Monon Trail Monon Juan Solomon Park N MERIDIAN ST. E 61ST ST. E 61ST ST. Dan Wakefield Park INDYGO RED LINE BUS RAPID TRANSIT KESSLER BLVD E DR. KESSLER BLVD E DR. KESSLER BLVD E DR. Friedman Park N MERIDIAN ST. MERIDIAN N WESTFIELD BLVD. The Riviera Club Monon Trail Monon Canterbury 56TH ST. Park WINTHROP AVE. GUILFORD AVE. COLLEGE AVE. CENTRAL AVE. MERIDIAN ST. ILLINOIS ST. N CAPITOL AVE. er White Riv 54TH ST. 54TH ST. Highland Golf Country Club WESTFIELD BLVD.54TH ST. Rocky Ripple 52ND ST. 52ND ST. 52ND ST. Holcomb Gardens E 49TH ST. 49TH ST E 49TH ST. Butler Arsenal Park University AVE. SUNSET Central Canal Trail E 46TH ST. E 46TH ST. MICHIGAN RD. COLLEGE AVE. CENTRAL AVE. MERIDIAN ST. COLD SPRING RD. N CAPITOL AVE. ILLINOIS ST. EVAANSTON AVE. HAMPTION DR. HAUGHEY AVE. HAUGHEY INDYGORED LINEBUS RAPID TRANSIT 43RD ST. 43RD ST. Andrew COLD SPRING RD. Ramsey Park E 42ND ST. E 42ND ST. Central Canal Trail Monon Trail MICHIGAN RD. 42ND ST. Tarkington Park Crown Hill Cemetary Fall Creek Trail Newfields 38TH ST. 38TH ST. INDYGO RED LINE BUS RAPID TRANSIT 38TH ST. Watson Road Bird Preserve Woodstock Riverside Country Club Golf Academy Lake Sullivan Sports Complex & E FALL CREEK PKWY DR. -

Destination Fall Creek Scheduling & Funding Plan

DESTINATION FALL CREEK SCHEDULING & FUNDING PLAN July 2013 Funded by LISC and the Indianapolis Foundation (an affiliate of CICF) in partnership with MFCDC, KPADC, NNDC & UNEDC DESTINATION FALL CREEK SCHEDULING & FUNDING PLAN July 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4......................REDEVELOPMENT CONCEPTS 5......................BICYCLE AND PEDESTRIAN CONNECTIVITY 8......................FALL CREEK GREENWAY TRAILHEAD AT 38TH STREET 10....................MONON ACCESS 12....................DELAWARE STREET GATEWAY 14....................MERIDIAN STREET CORRIDOR REDEVELOPMENT CONCEPTS DESTINATION FALL CREEK SCHEDULING & FUNDING PLAN AREAS OF ANALYSIS DESTINATION FALL CREEK IMPLEMENTATION PLAN As the planning team became better aquainted with ! ! ! ! ! Destination Fall Creek, it became apparent that the FALL CREEK PARKWAY AS A COMPLETE STREET ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! planning area was made up of a series of areas with ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Currently, Fall Creek Parkway is not a complete street. In fact, it ! ! ! different qualities created by particular combinations or ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! types of land use, different histories, unique assets and ! ! ! is a Primary Arterial that moves a high volume of through traffic ! ! ! ! ! ! ! challenges. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! at high speeds and does not primarily function to serve abutting ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! The areas are a planning tool, and not meant to have ! ! ! ! ! 1! land uses, A road diet can transform the parkway into a complete ! ! hard and definite edges. They do not necessarily respect ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

INDY GREENWAYS the Indy Greenways Patch Is a Local Patch Program That Teaches Central Indiana Girl Scouts About the Indy Greenways System

INDY GREENWAYS The Indy Greenways patch is a local patch program that teaches central Indiana Girl Scouts about the Indy Greenways system. The intent of the program is to raise awareness and educate young kids on the design, function, and proper use of the Indy Greenways and to demonstrate the important role that the greenways play in connecting local communities. It is also intended to instill a level of ownership, responsibility, and stewardship for the greenway system. The patch program aims to achieve the following objectives: Raise awareness of the Indy Greenways system, what it is, and how it is used. Provide a basic understanding of Indy Greenways and how to use the trails. Provide a basic understand of how trails and greenways benefit communities. Instill a responsibility for the ongoing stewardship of the greenways system. Instill a general interest on how the greenways can be a part of Girl Scouts’ everyday lives. Getting Started This program has been developed to accommodate multiple age levels of girl scout troops, with specific focus on the following grade levels: • Girl Scout Daisies, Brownies and Juniors - grades K-5. • Girl Scout Cadettes- grades 6-8. Troop leaders should modify the program as needed to accommodate specific troop age and grade levels. Program Overview The program includes three basic elements that must be completed in order to achieve the Indy Greenways patch: Learn Indy Greenways (Educational Component) - a troop- facilitated educational session that introduces Indy Greenways, its purpose, and other important facts about the greenways and their use. The educational component includes research and discussion that can be led by volunteer troop leaders and can be completed within an one-hour working session (troop meeting). -

Fort Benjamin Harrison: from Military Base to Indiana State

FORT BENJAMIN HARRISON: FROM MILITARY BASE TO INDIANA STATE PARK Melanie Barbara Hankins Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Department of History, Indiana University April 2020 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D., Chair ____________________________________ Rebecca K. Shrum, Ph.D. ____________________________________ Anita Morgan, Ph.D. ii Acknowledgements During my second semester at IUPUI, I decided to escape the city for the day and explore the state park, Fort Benjamin Harrison State Park. I knew very little about the park’s history and that it was vaguely connected to the American military. I would visit Fort Harrison State Park many times the following summer, taking hikes with my dog Louie while contemplating the potential public history projects at Fort Harrison State Park. Despite a false start with a previous thesis topic, my hikes at Fort Harrison State Park inspired me to take a closer look at the park’s history, which eventually became this project. Finishing this thesis would have been nearly impossible without the encouragement and dedication of many people. First, I need to thank my committee: Dr. Philip Scarpino, Dr. Rebecca Shrum, and Dr. Anita Morgan for their criticism, support, and dedication throughout my writing process. I would especially like to thank my chair, Dr. Scarpino for his guidance through the transition of changing my thesis topic so late in the game. -

Task 4/6 Report: Programming & Destinations

Tasks Four/Six: Destinations and Programming In these tasks, the team developed an understanding for destinations, events, programming, and gathering places along the White River. The team evaluated existing and potential destinations in both Hamilton and Marion Counties, and recommended new catalyst sites and destinations along the River. The following pages detail our process and understanding of important destinations for enhanced or new protection, preservation, programming and activation for the river. Core Team DEPARTMENT OF METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT HAMILTON COUNTY TOURISM, INC. VISIT INDY RECONNECTING TO OUR WATERWAYS Project Team AGENCY LANDSCAPE + PLANNING APPLIED ECOLOGICAL SERVICES, INC. CHRISTOPHER B. BURKE ENGINEERING ENGAGING SOLUTIONS FINELINE GRAPHICS HERITAGE STRATEGIES HR&A ADVISORS, INC. LANDSTORY LAND COLLECTIVE PORCH LIGHT PROJECT PHOTO DOCS RATIO ARCHITECTS SHREWSBERRY TASK FOUR/SIX: DESTINATIONS AND PROGRAMMING Table of Contents Destinations 4 Programming 18 Strawtown Koteewi 22 Downtown Noblesville 26 Allisonville Stretch 30 Oliver’s Crossing 34 Broad Ripple Village 38 Downtown Indianapolis 42 Southwestway Park 46 Historic Review 50 4 Destinations Opportunities to invest in catalytic projects exist all along the 58-mile stretch of the White River. Working together with the client team and the public, the vision plan identified twenty-seven opportunity sites for preservation, activation, enhancements, or protection. The sites identified on the map at right include existing catalysts, places that exist but could be enhanced, and opportunities for future catalysts. All of these are places along the river where a variety of experiences can be created or expanded. This long list of destinations or opportunity sites is organized by the five discovery themes. Certain locations showed clear overlap among multiple themes and enabled the plan to filter through the long list to identify seven final sites to explore as plan ‘focus areas’ or ‘anchors’. -

Indy Greenways IMPLEMENTATION.Indd

White River Greenway chapter six IMPLEMENTATION chapter six IMPLEMENTATION inside this chapter: SYSTEM BUILD OUT RECOMMENDATIONS Methodology . 273 Part A: Impact Assessment . 273 Part B: Weighted Infl uences . 276 General Interpretation & Prioritization . .276 POLICY & ADMINISTRATIVE RECOMMENDATIONS A. Hours of Operation . 279 B. Seasonal Operations . 281 C. Greenway Oversight . 283 D. Maintenance Policies. 285 E. Media & Technology Platforms . 291 F. Partnerships, Sponsorships & Donors. .296 G. Regulatory Tools. .298 ACTION PLAN AGENDA Action Plan Matrices. 301 CHAPTERimplementation 6 he adoption of the 2014-24 Indy Greenways Full Circle Plan is the fi rst step in implementation. It is acknowledged that this is a long-term strategy, and as such this T chapter outlines key steps in the ongoing process. This section is divided into three parts: 1. System Build Out – This section provides an overview of the prioritization of the various segments’ ultimate build-out. It describes a methodology for how the various segments were divided into short, medium and long-term design, engineering and construction priorities. There is a recognition that circumstances may arise that would modify this prioritization (such as land availability or funding opportunities), but this should be used as a general guide in the ongoing growth of the greenway system. 2. Policy & Administrative Recommendations – This section outlines several plan recommen- dations not specifi cally related to design and construction activities. These include such items as administrative function, maintenance and coordination of city regulatory tools. 3. Action Plan – This section summarizes the overall plan recommendations and highlights the key implementing agencies, partners, funding sources, action type, timeline and supporting plan goals Implementation of any project as complex as the Indy Greenways requires involvement from dozens of public, private and other support organizations. -

Citizens Reservoir Frequently Asked Questions Comparison Chart

09/22/2020 Citizens Reservoir Frequently Asked Questions What is the Citizens Reservoir? Why do we need Geist Reservoir and Citizens Reservoir is an over three billion gallon Citizens Reservoir? water storage facility to be constructed in a The Indianapolis area receives approximately 42 retired limestone quarry adjacent to Citizens inches of rain annually; however, the water supply Energy Group’s Geist Reservoir along Olio Road. is not always available when needed. Heavy rain in excess of Geist Reservoir’s storage capacity How big is the Citizens Reservoir? now flows downstream over the dam. During dry At approximately 230 feet deep, the Citizens periods, stream flows and reservoir supplies can be Reservoir depth is nearly equivalent to the height strained. Citizens Reservoir will store some of the of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument. The 90-acre raw water from excess precipitation that now spills Citizens Reservoir will be able to hold nearly half over the Geist Dam for use during dry periods. the volume of the 1,800 acre Geist Reservoir. The additional volume is enough to provide a year of How will excess water be captured for supply? water supply for over 100,000 Hoosiers. This will be accomplished by diverting excess flow from Geist Reservoir through an intake What purpose does the reservoir serve? structure located between Geist Reservoir and Citizens Reservoir will create a more resilient Citizens Reservoir. The intake structure will allow water supply for Citizens Energy Group’s approximately 100 million gallons per day of customers. Construction of the reservoir will otherwise unutilized water into Citizens Reservoir. -

Hancock County Part B Update 10 2010

NPDES PHASE II MS4 GENERAL PERMIT STORM WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN PART B: BASELINE CHARACTERIZATION REPORT UPDATE HANCOCK COUNTY, INDIANA PERMIT #INR040128 OCTOBER 30, 2010 NPDES PHASE II STORM WATER QUALITY MANAGEMENT PLAN (SWQMP) PART B: BASELINE CHARACTERIZATION REPORT UPDATE Prepared for: Hancock County, Indiana October 2010 Prepared by: Christopher B. Burke Engineering, Ltd. National City Center, Suite 1368-South 115 W. Washington Street Indianapolis, Indiana 46204 CBBEL Project Number 03-463 DISCLAIMER: Exhibits and any GIS data used within this report are not intended to be used as legal documents or references. They are intended to serve as an aid in graphic representation only. Information shown on exhibits is not warranted for accuracy or merchantability. Hancock County, Indiana NPDES Phase II SWQMP Part B: Baseline Characterization Report Update TABLE OF CONTENTS Page # 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 LAND USE WITHIN MS4 AREA 2 2.1 DESCRIPTION OF MS4 AREA 2 2.2 POPULATION DATA 2 2.3 LAND USE DATA 3 2.4 WATERSHEDS WITHIN MS4 AREA 3 2.5 SUMMARY OF LAND USE EVALUATIONS 4 3.0 SENSITIVE AREA 5 3.1 ERODIBLE SOIL 5 3.2 SOIL SUITABLITY FOR SEPTIC SYSTEMS 5 3.3 NATURAL HERITAGE DATA 6 3.4 WETLANDS 6 3.5 OUTSTANDING AND EXCEPTIONAL USE WATERS 7 3.6 ESTABLISHED TMDL WATERS 7 3.7 RECREATIONAL WATERS 7 3.8 PUBLIC DRINKING WATER SOURCES 7 3.9 SUMMARY OF SENSITIVE AREA CONCLUSIONS 8 4.0 SUMMARY OF EXISTING MONITORING DATA 9 4.1 INDIANA INTEGRATED WATER MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT REPORT 9 4.2 UNITED STATES GEOLOGIC SURVEY (USGS) STUDIES 9 4.3 STREAM REACH CHARACTERIZATION EVALUATION REPORT 10 4.4 CLEAN WATER ACT CHAPTER 319 GRANT STUDIES 11 4.5 HEALTH DEPARTMENT STUDIES 11 5.0 IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT OF EXISTING BMPs 12 i Christopher B. -

Mccordsville Bike and Pedestrian Master Plan DRAFT

McCordsville Bike and Pedestrian Master Plan DRAFT October 11, 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Public Input 2 Existing Conditions 3 Proposed Conditions 4 Implementation 5 Appendix 6 add more detail McCordsville Bike and Pedestrian Master Plan 1 SUMMARY MCCORDSVILLE BIKE AND PEDESTRIAN MASTER PLAN 2 SUMMARY City of McCordsville Design Team Tonya Galbraith - Town Manager Ryan Crum - Director of Planning and Building Stakeholders CONTEXT DESIGN Maria Bond - Director of Community Relations / Mt. Vernon Schools Project Lead, Landscape Architects Stephanie Miller - Principal / McCordsville Elementary Hancock Flat 50 Member - Joe Mayes, Project Manager Bridgette Cook-Jones - Hancock County Tourism Director - Ben Kay, Project Manager Support Christine Owens - Cumberland Assistant Town Manager & Planner Adam Zaklikowski - Fortville Planning Administrator Steve Long - Hancock Health Randy Sorrell - HEDC Director Flory May - Vernon Township Trustee Mel Branson - Buck Creek Township Trustee Bob Bronson - IN DNR Jason Taylor - Fishers City Engineer Susan Bodkin - County Surveyor CMT Keith Lash - Residential developer - VP Lennar Homes Engineering Tom Willey - Commercial Developer - Reliant Partners Aimee Ector - Business owner - Second Stories - Cassie Reiter, Project Engineer John Jokantas - Resident, trail supporter, County E911 Director - Scott Hanson, Project Planner Anna Gremling - MPO City of Lawrence representative Aletha Dunston - Ft. Ben Re-use Authority Director Joe Mitchell - Executive Minister / Outlook Christian Church Scott -

Central Canal Towpath Extension • Pa-17-006B Csx Railroad Repurpose - 30Th Street - Burdsall Parkway

CENTRAL CANAL TOWPATH EXTENSION • PA-17-006B CSX RAILROAD REPURPOSE - 30TH STREET - BURDSALL PARKWAY 29th St Central Canal r wy N D Pk ek re Interstate 65 C ll Burdsal a F W Fall Creek Meridian St Current Fall Creek Trail Phase 1 (PA-24-009) Phase 2 (PA-24-008) PROJECT DETAILS This repurposing of an abandoned CSX Railroad line from 30th Street to Burdsall Parkway will supplement the Central PROJECT NUMBER: PA-17-006B Canal Towpath extension, which will connect the Fall Creek PROJECT STATUS: In Construction Trail Phase I and the White River Trail at Indiana Avenue ANTICIPATED CONSTRUCTION PERIOD: and 10th Street projects. When complete, the Central January to July 2020 Canal Towpath will provide users with an aggregate trail, ESTIMATED CONSTRUCTION COST: $800K concrete sidewalks, curbs and ADA ramps and will join the NEIGHBORHOODS: Riverside, QuestEnd, overall plan to connect downtown Indianapolis with Fort WestSide, Haughville, Benjamin Harrison State Park. FOR MORE INFORMATION [email protected] 317-327-2656 • indy.gov/DPW The Indianapolis Department of Public Works (DPW) continues to transform Indianapolis neighborhoods through the restoration of deteriorating thoroughfares, residential streets, sidewalks and bridges, as well as addressing neighborhood drainage and flooding issues. This investment continues to transform neighborhoods throughout Indianapolis. These projects create local jobs and increase public safety for neighborhoods and residents, which support DPW’s commitment to make Indianapolis a more livable city. K S C F HOMEOWNER RESPONSIBILITIES ow grass to 8 inches or less Keep ditches free of high grasses and debris Remoe trash and litter blocking Pick up after pets stormwater inlets Clear away any leaes from storm drains nly rain belongs in the storm drain aintain clean and clear culerts The stormwater system ends in our waterways ets keep it clean and draining uickly.