Volume 3, Number 1 (Spring 2007)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 2019 Whole No

Dedicated to the Study of Naval and Maritime Covers Vol. 86 No. 7 July 2019 Whole No. 1028 July 2019 IN THIS ISSUE Feature Cover From the Editor’s Desk 2 Send for Your Own Covers 2 Out of the Past 3 Calendar of Events 3 Naval News 4 President’s Message 5 The Goat Locker 6 For Beginning Members 8 West Coast Navy News 9 Norfolk Navy News 10 Chapter News 11 Fleet Week New York 2019 11 USS ARKANSAS (BB 33) 12 2019-2020 Committees 13 Pictorial Cancellations 13 USS SCAMP (SS 277) 14 One Reason Why we Collect 15 Leonhard Venne provided the feature cover for this issue of the USCS Log. His cachet marks the 75th Anniversary of Author-Ship: the D-Day Operations and the cover was cancelled at LT Herman Wouk, USNR 16 Williamsburg, Virginia on 6 JUN 2019. USS NEW MEXICO (BB 40) 17 Story Behind the Cover… 18 Ships Named After USN and USMC Aviators 21 Fantail Forum –Part 8 22 The Chesapeake Raider 24 The Joy of Collecting 27 Auctions 28 Covers for Sale 30 Classified Ads 31 Secretary’s Report 32 Page 2 Universal Ship Cancellation Society Log July 2019 The Universal Ship Cancellation Society, Inc., (APS From the Editor's Desk Affiliate #98), a non-profit, tax exempt corporation, founded in 1932, promotes the study of the history of ships, their postal Midyear and operations at this end seem to markings and postal documentation of events involving the U.S. be back to normal as far as the Log is Navy and other maritime organizations of the world. -

Texas Clipper

Environmental Remediation of the Texas Clipper ENVIRONMENTAL REMEDIATION OF THE USTS TEXAS CLIPPER FOR USE AS AN ARTIFICIAL REEF IN THE GULF OF MEXICO 7 September 2007 Submitted by: Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Artificial Reef Program 4200 Smith School Rd. Austin, TX 78744-3291 (512) 389-4686 Environmental Remediation of the Texas Clipper TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..............................................................................................................I LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... III LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... III ACRONYMS............................................................................................................................... IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ VI PART 1.0 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Overview of the Texas Artificial Reef Program....................................................................... 1 1.2 Use and Acquisition of the Texas Clipper Ship as an Artificial Reef ...................................... 1 1.3 Goal of Texas Clipper Ship Artificial Reef Project.................................................................. 5 1.3.1 Conservation Goals............................................................................................................... -

Lead and Line April

April 2015 volume 3 0 , i s s u e N o . 4 LEAD AND LINE newsletter of the naval Association of canada-vancouver island Buzzed by Russians...again At sea with Victoria Monsters be here Another cocaine bust Page 2 Page 3 Page 9 Page 14 HMCS Victoria Update... Page 3 Speaker: Captain Bill Noon NAC-VI Topic: Update on the Franklin Expedition 27 Apr Cost will be $25 per person. Luncheon Guests - spouses, friends, family are most welcome Please contact Bud Rocheleau [email protected] or Lunch at the Fireside Grill at 1130 for 1215 250-386-3209 prior to noon on Thursday 19 Mar. 4509 West Saanich Road, Royal Oak, Saanich. NPlease advise of any allergies or food sensitivities Ac NACVI • PO box 5221, Victoria BC • Canada V8R 6N4 • www.noavi.ca • Page 1 April 2015 volume 30 , i s s u e N o . 4 NAC-VI LEAD AND LINE Don’t be so wet! There has been a great kerfuffle on Parliament Hill, and in the press, about the possibility that HMCS Fredericton might have been confronted by a Russian warship and buzzed by Russian fighter jets. Not so says NATO, stating that any Russian vessels were on the horizon and the closest any plane got was 69 kilometers. (Our MND says it was within 500 ft!) An SU-24 Fencer circled HMCS Toronto, during NATO op- And so what if they did? It would hardly be surprising, if erations in the Black Sea last September. in a period of some tension (remember the Ukraine) that a Russian might be interested in scoping out the competition And you can’t tell me that the Americans (who were with us or that we might be interested in doing the same in return. -

HMCS Annapolis (DND Photo)

ANNAPOLIS – WARSHIP TO REEF R. A. (Rick) Wall, LCdr (ret'd) Volunteer Director – Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia Annapolis Project Navy Liaison Figure 1: HMCS Annapolis (DND photo) EVOLUTION OF A WARSHIP A familiar sight in Esquimalt Harbour for the last decade is the stripped out hull of the former HMCS Annapolis. Paid off in 1998, she has been tied up to the Fleet Diving Unit jetty in Esquimalt, BC for 8 years; a reminder to many of us of the days when steam powered ships dominated the world’s navies. Annapolis was the last of the West Coast based steam powered, Helicopter Destroyers (DDH). Her design can be traced back to the successful ST LAURENT Class Destroyer Escorts (DDE), which, in addition to being the first postwar destroyer design in the world, was also the first major class of warship designed and built entirely in Canada (7 built between 1955 and 1957). Ordered in 1948, the ST LAURENT design was similar to the British Type 12 WHITBY Class frigate but used more American equipment. Of note were such innovations as the incorporation of an operations room from which the Captain fought the ship and the provision of chemical, biological & radiation/nuclear (CBRN) protection. With the advances in fighting capabilities and the crew comfort that were integrated into the Class, these ships were commonly referred to as the “Cadillac of Destroyers” by the sailors who sailed in them. Being a successful design, a further seven anti-submarine ships were ordered in 1951 by the Canadian Government. Referred to as the RESTIGOUCHE Class, they were built between 1953 and 1959. -

A Review of California's Artificial Reefs

A REVIEW OF CALIFORNIA’S ARTIFICIAL REEFS: To help inform future development of a statewide management plan. STUDENT NAME: J. Liz Hunter DEGREE NAME: Masters of Advanced Studies Marine Biodiversity and Conservation DEPARTMENT: Scripps Institution of Oceanography INSTITUTION: University of California San Diego COMMITTEE CHAIR: Ms. Catherine Courtier Research and Extension Analyst- Science Integration Team California Sea Grant COMMITTEE MEMBER: Mr. Brian Owens, Senior Marine Biologist, Specialist Habitat Conservation Program, Marine Region Brian Owens California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Lyall Bellquist Fisheries Scientist, California Oceans Program The Nature Conservancy COMMITTEE MEMBER: Dr. Richard Norris Geosciences Research Division UCSD Professor of Paleobiology Abstract The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) has been involved in the construction of artificial reefs (ARs) since the 1950s. Then in 1985, the California Artificial Reef Program (CARP) was created by legislative statute to address declines in various southern California marine species. The CARP is managed by CDFW but no longer receives funding to manage this program. Before CDFW can support further creation of ARs we need to identify gaps in the program and know how ARs affect marine species and the marine ecosystems. This will ultimately inform a scientifically based statewide AR management plan, which CDFW needs to support in the program. The first step into making informed management decisions of the ARs is to complete a literature review of published material and to survey the type, number, and placement of ARs. The results of this survey need to be standardized and transparent in order for the CDFW to review, compare, and make informed management decisions. -

Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS

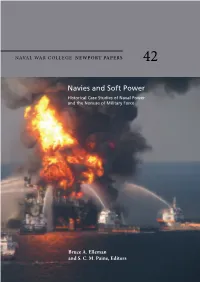

NAVAL WAR COLLEGE NEWPORT PAPERS 42 NAVAL WAR COLLEGE WAR NAVAL Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force NEWPORT PAPERS NEWPORT 42 Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, Editors U.S. GOVERNMENT Cover OFFICIAL EDITION NOTICE The April 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil-rig fire—fighting the blaze and searching for survivors. U.S. Coast Guard photograph, available at “USGS Multimedia Gallery,” USGS: Science for a Changing World, gallery.usgs.gov/. Use of ISBN Prefix This is the Official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its au thenticity. ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4 (e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1) is for this U.S. Government Printing Office Official Edition only. The Superinten- dent of Documents of the U.S. Government Printing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled as a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Legal Status and Use of Seals and Logos The logo of the U.S. Naval War College (NWC), Newport, Rhode Island, authenticates Navies and Soft Power: Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force, edited by Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, as an official publica tion of the College. It is prohibited to use NWC’s logo on any republication of this book without the express, written permission of the Editor, Naval War College Press, or the editor’s designee. For Sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-00001 ISBN 978-1-935352-33-4; e-book ISBN 978-1-935352-34-1 Navies and Soft Power Historical Case Studies of Naval Power and the Nonuse of Military Force Bruce A. -

Hmcs Moncton

Volume 28, Number 4 Fall 2019 HMCS MONCTON HMCS Moncton, resplendent in a Second World War Admiralty disruptive paint scheme (Dazzle pattern) in honour of the 75th anniversary of the end of the Battle of the Atlantic. From the Editor: SCOTT HANWELL Let me begin this issue by apologizing for my overly identified by an appropriately coloured ensign. This political comments in my last Letter from the Editor. I practice remained in place until 1864 when the Royal was quite rightly reminded that NMAS is apolitical – I Navy standardized the White Ensign for all HM Ships. As will seek better forums to vent my spleen in the future. an interesting side note, the Canadian Red Ensign was October is the month when our thoughts naturally the unofficial national flag of Canada for many years. It turn to the Battle of Trafalgar and the uncompromising was formed by a standard Red Ensign debruised with tactics of Admiral Lord Nelson in “crossing the T”. the Arms of Canada. In this letter, however, I wanted to cast a glance a bit Which leads me to the name of this publication and farther back and discuss General-at-Sea Robert Blake. I the reminder that Canadian sailors went to sea with think Blake is unfairly overlooked and while he is known the White Ensign proudly hoisted on HMC ships until as the Father of the Royal Navy, his accomplishments 1965. As I’m sure you know, presently HMC Ships hoist rarely gain the commemoration of Nelson’s. the Canadian Naval Ensign (formerly Jack) at the stern Blake’s 17th Century victories over the Dutch were and the National Flag of Canada from the Jack Staff – a certainly as pivotal as Trafalgar and they established the practice in keeping with British tradition. -

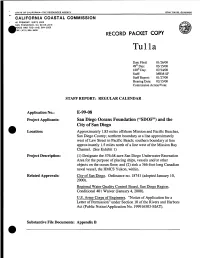

RECORD PACKET COPY Tulla

,_ STATE OF CALIFORNIA-THE RESOURCES AGENCY GRAY DAVIS, GOVERNOR CALIFORNIA COASTAL COMMISSION 45 FREMONT, SUITE 2000 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105-2219 OICE AND TOO (415) 904-5200 AX ( 415) 904- 5400 • RECORD PACKET COPY Tulla Date Filed: 01126/00 49th Day: 03/15/00 1 180 h Day: 07/24/00 Staff: MBM-SF StaffReport: 01127/00 Hearing Date: 02/15/00 Commission Action/Vote: STAFF REPORT: REGULAR CALENDAR Application No.: E-99-08 Project Applicants: San Diego Oceans Foundation ("SDOF") and the City of San Diego Location: Approximately 1.85 miles offshore Mission and Pacific Beaches, San Diego County; northern boundary at a line approximately • west of Law Street in Pacific Beach; southern boundary at line approximately 1.5 miles north of a line west of the Mission Bay Channel. (See Exhibit 1) Project Description: (1) Designate the 576.68-acre San Diego Underwater Recreation Area for the purpose of placing ships, vessels and/or other objects on the ocean floor; and (2) sink a 366-foot long Canadian naval vessel, the HMCS Yukon, within. Related Approvals: City of San Diego. Ordinance no. 18741 (adopted January 10, 2000). Regional Water Quality Control Board, San Diego Region. Conditional 401 Waiver (January 4, 2000). U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. "Notice of Application for a Letter of Permission" under Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act (Public Notice/Application No. 199916503-MAT). • Substantive File Documents: Appendix B E-99-08 (San Diego Oceans Foundation and City of San Diego) Page 2of54 SYNOPSIS The San Diego Oceans Foundation and the City of San Diego are joint applicants in this application to (1) designate the 576.68-acre San Diego Underwater Recreation Area ("SDURA") • and (2) sink a 366-foot long decommissioned Canadian naval vessel, the HMCS Yukon, within. -

UNTD –VIP List

UNTD Alumni (University Naval Training Division) Some Occupations/Awards/Titles - as of Aug 3, 2015 (Replaces List dated Sep 13, 2013) 444 Cadets - by Name (1943 to 1968 = 436) + (1969 to present = 8) A: • ABBOTT, Frederick F [DONNACONA '52] Fellow - Institute of Chartered Accountants of Alberta Chair - Board of Governors - Glenbow Museum – Calgary • ABRAMOFF, Peter [HUNTER '48] Professor Emeritus - Biological Sciences - Marquette University - Milwaukee, WI Author - Technical Books and Articles • AFFLECK, Kenneth N [DISCOVERY '63] Judge - Supreme Court of British Columbia (Vancouver) • AGNEW, George Howard (Howard) [CHIPPAWA '52] † Chief Operating Officer - Texaco Canada • AITKEN, David M [CHIPPAWA 56] Fellow - Royal Architectural Society of Canada Founder - Aitken Leadership Group President - Architectural Institute of BC • ALLAN, John (Jock) [CATARAQUI '50] † Vice Admiral - Canadian Forces - Canadian Navy Deputy Chief of the Defence Staff - Canadian Forces Commander Maritime Command - Canadian Forces (Head of the Navy) Commanding Officer - 1st Canadian Destroyer Squadron Commanding Officer - HMCS QU'APPELLE - DDE-264 – Destroyer • ALLEN, Robert Wendell [DISCOVERY '60] Commanding Officer - HMCS MARGAREE - DDH-230 - Destroyer Commanding Officer - HMCS PRESERVER - AOR-510 - Fleet Replenishment • ALSGARD, Stewart Brett [DISCOVERY '53] Mayor - City of Powell River, BC Provincial Coroner - British Columbia Commandant - Naval Reserve Training Centre - CFB Esquimalt Commanding Officer - HMCS DISCOVERY - Naval Reserve Division - Vancouver, BC -

C S a S S C C S

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2006/059 Document de recherche 2006/059 Not to be cited without Ne pas citer sans permission of the authors * autorisation des auteurs * The intentional scuttling of surplus Sabordage intentionnel de navires en and derelict vessels: Some effects on surplus et épaves : quelques effets marine biota and their habitats in sur le biote marin et sur les habitats British Columbia waters, 2002 dans les eaux de la Colombie- Britannique, 2002 B.D. Smiley Department of Fisheries and Oceans Marine Environment and Habitat Science Division Institute of Oceans Sciences 9860 West Saanich Road, Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 Canada * This series documents the scientific basis for the * La présente série documente les bases evaluation of fisheries resources in Canada. As scientifiques des évaluations des ressources such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time halieutiques du Canada. Elle traite des frames required and the documents it contains are problèmes courants selon les échéanciers dictés. not intended as definitive statements on the Les documents qu’elle contient ne doivent pas subjects addressed but rather as progress reports être considérés comme des énoncés définitifs on ongoing investigations. sur les sujets traités, mais plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue -

Ecological Assessment of the HMCS Yukon Artificial Reef Off San Diego, CA (USA)

Ecological Assessment of the HMCS Yukon Artificial Reef off San Diego, CA (USA) by Ed Parnell1 January 7, 2005 1Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Integrative Oceanography Division, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093-0227 Prepared for: The San Diego Oceans Foundation P.O. Box 90672 San Diego, CA 92169-2672 http://www.sdoceans.org Sponsor: California Artificial Reef Enhancement Program 1008 Tenth Street, Suite 298 Sacramento, CA 95814 http://www.calreefs.org Ecological Assessment of the HMCS Yukon Artificial Reef off San Diego, CA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY inception of the monitoring program. Many of the species that first colonized the ship were The San Diego Oceans Foundation sank the species whose ambits are large and which likely HMCS Yukon, a decommissioned Canadian move among nearby artificial and natural destroyer escort (~112m long), off San Diego in habitats. Secondary colonization of the ship is 2000 as an artificial reef to support diving ongoing and consists of fish that are residential recreation, fishing, scientific research and and have recruited to the ship and species education. The Foundation then developed and whose ambits are generally smaller than the conducted a volunteer based monitoring early colonizers but whose abundances are program of the Reef to determine the variable. colonization of marine life on the ship over time and to gauge its ecological effects. The Sheephead and boccacio, two species that are monitoring program is still ongoing and the highly targeted by commercial and sports Foundation plans to continue the program fishers, successfully recruit onto the Yukon. indefinitely. Here, I report the results of the Blacksmith, a non-targeted species, also appear monitoring program four years after the to successfully recruit on the ship. -

On This Day in the Canadian Navy!

On this day in the Canadian Navy! MAY In May 1914 The establishment of a Naval Volunteer Force by Order-in- Council. Three subdivisions are ordered with a total strength of 1,200 men. Annual cost estimated at $200,000.00. From the outset it is called the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve (RNCVR). May 03, 1937 A Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) Half Company is raised in Port Arthur, now Thunder Bay, Ontario. This unit would later become HMCS Griffon. May 04, 1910 The Naval Service Bill receives Royal Assent. It creates a Department of the Naval Service under the Minister of Marine and Fisheries, who will be the minister of the Naval Service, and authorizes the appointment of a Deputy Minister. A Naval Reserve Force and a Naval Volunteer Force are authorized, with both forces liable for active service in an emergency. A naval college is provided for in order to train prospective officers in all branches of naval science, strategy and tactics. The Naval Discipline Act of 1866, and King’s Regulations and Admiralty Instructions are to apply to the service. Two old cruisers, HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow are purchased from the Admiralty to be used as training ships. The naval college is established in Halifax. May 04, 1911 His Majesty’s Dockyard Esquimalt, British Columbia, transfers to Canadian control. May 04, 1945 U-boats are ordered to cease hostilities. May 04, 1945 The cruiser HMCS Uganda sails for the bombardment of Miyako Jima, Okinawa (Japan) with American task force. May 5, 1944 The River Class frigate HMCS Magog (K673) commissions into the Royal Canadian Navy.