St. Lucia Country Report (2019), Available At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SAINT LUCIA Dates of Elections: 6 and 30 April 1987 Purpose Of

SAINT LUCIA Dates of Elections: 6 and 30 April 1987 Purpose of Elections General elections were held on 6 April 1987 on the normal expiry of the Parliament's term, but the close polling results did not provide either one of the main contending parties with a clear mandate. The legislature was therefore dissolved on 14 April and new elections took place on 30 April. Characteristics of Parliament The bicameral Parliament of Saint Lucia consists of a Senate and a House of Assembly. The Senate is composed of 11 members appointed by the Governor-General: 6 on the advice of the Prime Minister, 3 on the advice of the Leader of the Opposition, and 2 on the basis of the Governor-General's "own deliberate judgement" after undertaking various consultations. The House of Assembly comprises 17 elected members. All parliamentarians have 5-year terms of office. Electoral System Every citizen of the Commonwealth who is at least 18 years old and possesses the required qualifications relating to residence or domicile in Saint Lucia is, unless otherwise disqualified, entitled to vote. All citizens of at least 21 years of age who were born in Saint Lucia and are domiciled and resident there at the date of their nomination (or having been born elsewhere, have resided there for a period of 12 months immediately before that date), as well as able to speak and - unless incapacitated by blindness or other physical cause - to read the English language with a degree of proficiency sufficient to enable them to take an active part in the proceedings of the House, are qualified to be elected as members of the House of Assembly; the age and residence requirements for Senate candidates are 21 and five years, respectively. -

Enhancing Leahy Law Human Rights Enforcement Through a Private Cause of Action

Valparaiso University Law Review Volume 51 Number 3 Spring 2017 pp.831-879 Spring 2017 To The People: Enhancing Leahy Law Human Rights Enforcement Through a Private Cause of Action Jess Hunter-Bowman Valparaiso University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jess Hunter-Bowman, To The People: Enhancing Leahy Law Human Rights Enforcement Through a Private Cause of Action, 51 Val. U. L. Rev. 831 (2017). Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/vulr/vol51/iss3/9 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Valparaiso University Law School at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Valparaiso University Law Review by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Hunter-Bowman: To The People: Enhancing Leahy Law Human Rights Enforcement Throu TO THE PEOPLE: ENHANCING LEAHY LAW HUMAN RIGHTS ENFORCEMENT THROUGH A PRIVATE CAUSE OF ACTION I. INTRODUCTION A sudden burst of machine-gun fire tore through the walls of Alfonso Bolivar Tuberquia’s home in rural Colombia.1 Seconds later, a grenade exploded, killing his wife, Sandra.2 Alfonso’s two young children miraculously survived the hail of bullets and shrapnel, prompting paramilitary commanders and their Colombian military allies to callously discuss what to do with the children.3 “Assassinate the kids, but silently,” a paramilitary commander ordered.4 A paramilitary fighter complied; he “took the child by the hair and slit her throat with a machete.”5 In total, eight civilians, including three children, were brutally massacred before paramilitaries and troops from the Colombian military’s Seventeenth Brigade marched out of San José de Apartadó.6 Days after the massacre, community members and human rights organizations alerted the U.S. -

International Relations and the Shaping of State-Societal Relations - a Postcolonial Study

International Relations and the Shaping of State-Societal Relations - a Postcolonial Study Ernest Hilaire London School of Economics and Political Science PhD. International Relations l UMI Number: U228692 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U228692 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Library 3C flO C » TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement 5 Abstract 6 Chapter 1: Understanding the Emergence of Postcolonial States 7 1.1: Some Preliminary Definitions 12 1.2: West Indian States in the International System 15 1.3: Formulating a Theoretical Approach 21 1.4: Thesis Outline 25 Chapter 2: Locating State and Society in International Relations Theory 29 2.1: The state of the State in IR Theory 30 2.2: Revisiting IR Theory - bringing in the ‘domestic’ 41 2.3: Reconceptualising the State 54 2.4: Moving Forward - A Critical Historical Approach 58 2.4.1: An Alternative Approach to IR Theory 58 2.4.2: Fundamentals of a Critical Historical Approach 61 Chapter 3: Understanding Postcolonial -

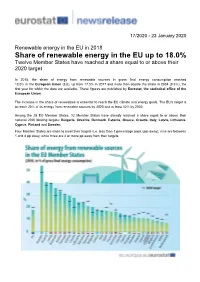

Share of Renewable Energy in the EU up to 18.0% Twelve Member States Have Reached a Share Equal to Or Above Their 2020 Target

17/2020 - 23 January 2020 Renewable energy in the EU in 2018 Share of renewable energy in the EU up to 18.0% Twelve Member States have reached a share equal to or above their 2020 target In 2018, the share of energy from renewable sources in gross final energy consumption reached 18.0% in the European Union (EU), up from 17.5% in 2017 and more than double the share in 2004 (8.5%), the first year for which the data are available. These figures are published by Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union. The increase in the share of renewables is essential to reach the EU climate and energy goals. The EU's target is to reach 20% of its energy from renewable sources by 2020 and at least 32% by 2030. Among the 28 EU Member States, 12 Member States have already reached a share equal to or above their national 2020 binding targets: Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Cyprus, Finland and Sweden. Four Member States are close to meet their targets (i.e. less than 1 percentage point (pp) away), nine are between 1 and 4 pp away, while three are 4 or more pp away from their targets. Sweden had by far the highest share, lowest share in the Netherlands In 2018, the share of renewable sources in gross final energy consumption increased in 21 of the 28 Member States compared with 2017, while remaining stable in one Member State and decreasing in six. Since 2004, it has significantly grown in all Member States. -

Nationwide May 06, 2006

Saint Lucia No. 136. Saturday, May 6, 2006 A publication of the Department of Information Services RENOVATED VICTORIAN ARCHITECTURE, BRAZIL ST., CASTRIES A section of the Soufriere-Vieux Fort Road “Take 2 ” - A fi fteen minute news review of the week. Government Notebook A fresh news package daily Every Friday at 6.15 p.m. on NTN, Cablevision Channel 2. on all local radio stations 2 Saint Lucia Saturday, May 6, 2006 THIS EDITION OF NATIONWIDE CONTINUES OUR SPECIAL COVERAGE OF THE 2006 – 2007 BUDGET PRESENTATION BY PRIME MINISTER AND MINISTER OF FINANCE DR. KENNY ANTHONY. THE FOLLOWING IS THE SECTION OF THE PRIME MINISTER’S SPEECH WHICH ADDRESSES THE QUESTION OF HOW GOVERNMENT WILL FINANCE THE COUNTRY’S FIRST BILLION DOLLAR BUDGET Now that the principal budgetary poli- This Government, Mr. Speaker, has al- which have been circulated to Honourable Honourable Members would also note cies have been outlined, I will proceed to ways erred on the side of caution in mak- Members. that work has commenced on Phase 1 of explain how the budget will be financed. ing projections of revenue and expendi- the Castries to Gros Islet Highway. This In formulating a budget, Mr Speaker, ture. We tend to be highly conservative Economic Service project, which covers the section of the we have the difficult task of striking the in our revenue estimates and as a result highway between Castries and Choc, will correct balance between taxes, expendi- tend to under-estimate. Conversely, our Agencies cause some discomfort to motorists. Once tures and debt. Our task is to ensure that precautionary approach leads us to over- The proposed allocation to the Eco- again, I plead for your patience and under- current and future generations are treated estimate recurrent expenditures. -

The Many Faces of Exclusion: 2018 End of Childhood Report

THE MANY FACES OF EXCLUSION END OF CHILDHOOD REPORT 2018 Six-year-old Arwa* and her family were displaced from their home by armed conflict in Iraq. CONTENTS 1 Introduction 3 End of Childhood Index Results 2017 vs. 2018 7 THREAT #1: Poverty 15 THREAT #2: Armed Conflict 21 THREAT #3: Discrimination Against Girls 27 Recommendations 31 End of Childhood Index Rankings 32 Complete End of Childhood Index 2018 36 Methodology and Research Notes 41 Endnotes 45 Acknowledgements * after a name indicates the name has been changed to protect identity. Published by Save the Children 501 Kings Highway East, Suite 400 Fairfield, Connecticut 06825 United States (800) 728-3843 www.SavetheChildren.org © Save the Children Federation, Inc. ISBN: 1-888393-34-3 Photo:## SAVE CJ ClarkeTHE CHILDREN / Save the Children INTRODUCTION The Many Faces of Exclusion Poverty, conflict and discrimination against girls are putting more than 1.2 billion children – over half of children worldwide – at risk for an early end to their childhood. Many of these at-risk children live in countries facing two or three of these grave threats at the same time. In fact, 153 million children are at extreme risk of missing out on childhood because they live in countries characterized by all three threats.1 In commemoration of International Children’s Day, Save the Children releases its second annual End of Childhood Index, taking a hard look at the events that rob children of their childhoods and prevent them from reaching their full potential. WHO ARE THE 1.2 BILLION Compared to last year, the index finds the overall situation CHILDREN AT RISK? for children appears more favorable in 95 of 175 countries. -

St. Lucia's Men of the Century

St. Lucias Men of The Century Sir George Charles William George Odlum Sir John Compton by Anderson Reynolds most propitious question to ask in outpouring of praise and affection. death, the Labor Government established this the 25th year of St. Lucia’s Newspaper articles eulogizing his death the George Charles Foundation with the Aindependence is: Who is the man carried titles like “A Man who Embodied a stated goal of institutionalizing the (or woman) of the century? Who above Movement and an Aspiration;” “A Secure education of generations to come on the anyone else has helped shape the history of Historical Legacy.” In his tribute to George life and contributions of George Charles. St. Lucia? Understandably, this is not an Charles the Prime Minister of St. Lucia, Dr. Clearly, from this national outpouring, Sir enviable task, because for a country that Kenny D. Anthony, said, “he was truly the George F.L. Charles would indeed be one has won two Nobel Prizes during its mere Father of Decolonization.” The radio of the nation’s candidates for man of the 25 years of independence (giving it the stations were inundated with citizens century. highest per capita of Nobel Laureates in calling in to talk about the goodness of The public life of George Charles the world), there is no shortage of George Charles, saying how he had taken began at the age of thirty, when, while candidates for this honor. Nonetheless, in money from his own pocket to help them working as a time keeper on the 1945 search of this St. -

Unmatched Power, Unmet Principles: the Human Rights Dimensions of US Training of Foreign Military and Police Forces

Unmatched Power, Unmet Principles: The Human Rights Dimensions of US Training of Foreign Military and Police Forces Amnesty International USA Publications Cover: Johor, Malaysia—U.S. Marines and Malaysian soldiers participate in a simulated amphibious assault during the seventh annual Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training 2001 exercise July 24. CARAT exercises employ simulated military scenarios designed to prepare U.S. and Malaysian forces to meet future challenges of disaster relief and humanitarian aid. CARAT, a series of bilateral exercises, takes place throughout the Western Pacific each summer. It aims to increase regional cooperation and promote interoperability with each country. The countries participating in CARAT 01 were: Indonesia, Singapore, Philippines, Thailand, Malaysia and Brunei. (U.S. Navy photo by Photographer's Mate 2nd Class Erin A. Zocco) In the mid 1990s, the US government revealed that for much of the previous decade the US Army's School of Americas (SOA) had used training manuals that advocated practices such as torture, extortion, kidnapping, and execution. While some curriculum changes have been implemented at this training institute, no one has ever been held accountable for the unlawful training manuals or for the behavior of SOA graduates. Further, the School of the Americas (now known as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation) is only one small part of vast and complex network of US programs for training foreign military and police forces that is often shrouded in secrecy. Such secrecy puts the United States at risk of training forces or individuals that commit human rights abuses. The United States government now trains at least 100,000 foreign police and soldiers from more than 150 countries each year in US military and policing doctrine and methods, as well as war-fighting skills, at the cost of tens of millions of dollars. -

Cybelle Cenac-Maragh Constitutional Reform of the Parliamentary System in Saint Lucia

Cybelle Cenac-Maragh Constitutional Reform of the Parliamentary System in Saint Lucia: A Comparative Analysis of Constitutional Changes in the Caribbean LLM 2015-2016 Advanced Legislative Studies (ALS) Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Cybelle Cenac Constitutional Reform of the Parliamentary System in Saint Lucia: A Comparative Analysis of Constitutional Changes in the Caribbean. LLM 2015-2016 LLM in Advanced Legislative Studies (ALS) Student number: 1441647 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4-9 CHAPTER 1 10-20 Historical Background Parliamentary System in Saint Lucia Separation of Powers Checks and Balances in the Parliamentary system CHAPTER 2 21-25 Reasons for Reform: Separation of Powers Despotic Government Parliamentary Corruption Proposal for Change CHAPTER 3 26-47 Westminster versus Washington Scrutiny of Legislation as a bar to Parliamentary Abuse Westminster/Republican Model in the Caribbean: Dominica, Trinidad & Tobago and Guyana CHAPTER 4 48-55 Can a distinct Separation of Powers be achieved? Could the Westminster Model Survive Successfully in a Caribbean context? Are there greater benefits to be derived from a unicameral or bicameral Parliament? Checks and Balances in a Unicameral Parliament. 2 CHAPTER 5 56-64 Recommendations CONCLUSION 65-67 BIBLIOGRAPHY 68-75 3 INTRODUCTION The parliamentary system under the Saint Lucian constitution is not fulfilling its purpose as intended, due to its perverse application, resulting in multiple abuses which can only be cured by a revision of that model to a hybrid parliamentary presidential one. Many commonwealth countries throughout the world, and indeed many Caribbean countries share a common parliamentary system, entrenched in their constitution, handed down by Britain. -

Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities

Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, SPM4 Coasts and Communities Coordinating Lead Authors: Michael Oppenheimer (USA), Bruce C. Glavovic (New Zealand/South Africa) Lead Authors: Jochen Hinkel (Germany), Roderik van de Wal (Netherlands), Alexandre K. Magnan (France), Amro Abd-Elgawad (Egypt), Rongshuo Cai (China), Miguel Cifuentes-Jara (Costa Rica), Robert M. DeConto (USA), Tuhin Ghosh (India), John Hay (Cook Islands), Federico Isla (Argentina), Ben Marzeion (Germany), Benoit Meyssignac (France), Zita Sebesvari (Hungary/Germany) Contributing Authors: Robbert Biesbroek (Netherlands), Maya K. Buchanan (USA), Ricardo Safra de Campos (UK), Gonéri Le Cozannet (France), Catia Domingues (Australia), Sönke Dangendorf (Germany), Petra Döll (Germany), Virginie K.E. Duvat (France), Tamsin Edwards (UK), Alexey Ekaykin (Russian Federation), Donald Forbes (Canada), James Ford (UK), Miguel D. Fortes (Philippines), Thomas Frederikse (Netherlands), Jean-Pierre Gattuso (France), Robert Kopp (USA), Erwin Lambert (Netherlands), Judy Lawrence (New Zealand), Andrew Mackintosh (New Zealand), Angélique Melet (France), Elizabeth McLeod (USA), Mark Merrifield (USA), Siddharth Narayan (US), Robert J. Nicholls (UK), Fabrice Renaud (UK), Jonathan Simm (UK), AJ Smit (South Africa), Catherine Sutherland (South Africa), Nguyen Minh Tu (Vietnam), Jon Woodruff (USA), Poh Poh Wong (Singapore), Siyuan Xian (USA) Review Editors: Ayako Abe-Ouchi (Japan), Kapil Gupta (India), Joy Pereira (Malaysia) Chapter Scientist: Maya K. Buchanan (USA) This chapter should be cited as: Oppenheimer, M., B.C. Glavovic , J. Hinkel, R. van de Wal, A.K. Magnan, A. Abd-Elgawad, R. Cai, M. Cifuentes-Jara, R.M. DeConto, T. Ghosh, J. Hay, F. Isla, B. Marzeion, B. Meyssignac, and Z. Sebesvari, 2019: Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. -

2018 Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy & International Broadcasting Focus on Fy 2017 Budget Data

N ON IO PU SS B I L M I C UNITED STATES M O D C I P L Y ADVISORY COMMISSION O R M O A S I C V Y D A ON PUBLIC DIPLOMACY 2018 COMPREHENSIVE ANNUAL REPORT ON PUBLIC DIPLOMACY & INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING FOCUS ON FY 2017 BUDGET DATA 1 TRANSMITTAL LETTER To the President, Congress, Secretary of State, and the American people: The United States Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy (ACPD), authorized pursuant to Public Law 112-239 [Sec.] 1280(a)-(c), hereby submits the 2018 Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy and International Broadcasting Activities. The ACPD is a bipartisan panel created by Congress in 1948 to formulate and recommend policies and programs to carry out the Public Diplomacy (PD) functions vested in U.S. government entities and to appraise the effectiveness of those activities across the globe. The ACPD was reauthorized in December 2016 to complete the Comprehensive Annual Report on Public Diplomacy and International Broadcasting Activities, as well as to produce other reports that support more effective efforts to understand, inform, and influence foreign audiences. This document details all reported major PD and international broadcasting activities conducted by the State De- partment and the U.S. Agency for Global Media (USAGM, also referred to in this report by its former name, the Broadcasting Board of Governors or the BBG). It is based on data collected from all State Department PD bureaus and offices, the Public Affairs Sections of U.S. missions worldwide, and from all USAGM entities. The 2018 report was researched, verified, and written by ACPD members and staff with continuous input and collaboration from State Department Public Diplomacy and USAGM officials. -

World Health Statistics 2018: Monitoring Health for the Sdgs, Sustainable Development Goals

2018 2018 ISBN 978 92 4 156558 5 2018 World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals ISBN 978-92-4-156558-5 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. World health statistics 2018: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.